Sole Power

About a decade ago, while teaching at the University of Winnipeg, I organized a team for an annual breast cancer fundraiser, the five-kilometre Run for the Cure. I went down my department’s corridor and knocked on colleagues’ doors, greeting them with the question, “Sponsor me?”

Hearing myself utter ted in the hallway like an echo from the past. A senior colleague replied to my expectant smile: “How far will you run?” Puzzled, I reminded him that it was a five-kilometre run and our team would have no trouble completing it.

As his eyes conveyed a sense of disappointment I was cast back decades: I was a schoolgirl in Toronto, facing neighbour after neighbour, asking that they “sponsor me” in exchange for my promise to push myself as far as I could go to help eradicate hunger around the world. I was marching in Miles for Millions, an event that would leave a deep imprint to be recalled decades later when I was an adult teaching history at the University of Winnipeg.

This incident — call it a nostalgia trigger — prompted me to do some historical sleuthing into what was an important annual feature of Canadian childhood and adolescence in the 1960s and ’70s.

Miles for Millions — Rallye Tiers Monde in Quebec — began in 1967 and lasted more than a decade. Its origins lay in the growing international fundraising practice of hunger marches spearheaded by organizations such as Oxfam. In Canada, the walkathon idea found highly receptive ground in the months leading up to the celebration of this country’s centennial.

In 1966, the Centennial International Development Program proposed to mark the occasion of Canada’s birth with a major gift to the developing world. Organizers saw a fundraising march as a way to help Third World countries while educating Canadians about international development.

From there came the idea for a series of marches across the country, in which thousands of people would walk as far as they could, having collected pledges from friends, family, neighbours, and local businesses.

Fed by the fervour of the centennial celebrations, the first Miles for Millions marches in 1967 drew great crowds and support.

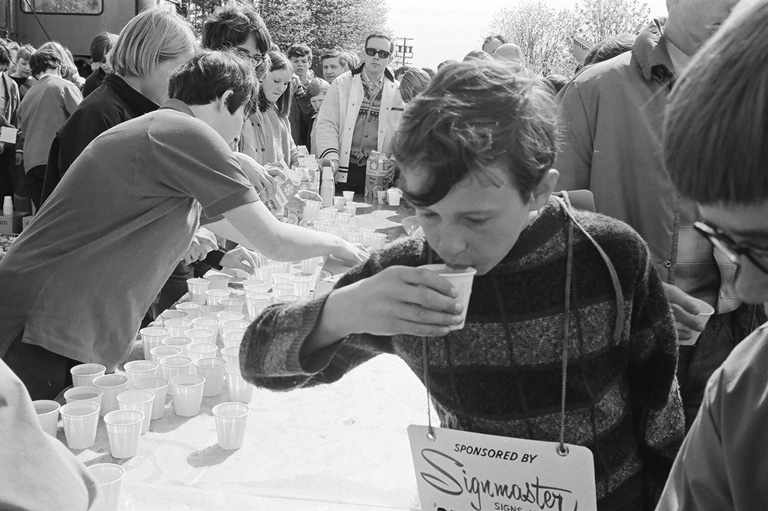

Twenty-two communities participated, drawing 100,000 walkers and raising $1.2 million.

The gruelling test of endurance became an annual event, drawing more walkers every year. It grew in popularity despite dramatic scenes of exhausted children who had been walking all day collapsing at the finish line in the arms of their parents.

Such images led a 1971 letter writer to the Globe and Mail to ask: “Do middle-class liberals hate children so much that they put them up to feats of utterly unnecessary endurance in order to win some measure of approval?”

It’s unlikely students joined just for approbation, however. In 1969, nearly half a million Canadians walked in 114 communities, raising almost $5 million. By 1973 the walks had raised $20 million for disaster relief work, medical care, agricultural development projects, and the like for countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean, as well as for First Nations peoples in Canada.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The Miles for Millions walks continued for more than a decade, coordinated by the Ottawa-based National March Committee formed by Oxfam Canada in conjunction with other international aid organizations.

In hindsight it seems astonishing that Miles for Millions was so popular, for this was no 5K event. It was born in the years prior to the jogging and aerobics crazes. It even predated ParticipACTION, a federal government program launched in 1971 that famously put the fitness of the average thirty-year-old Canadian on par with that of the average sixty-year-old Swede.

Canadians were unused to exerting themselves, yet Miles for Millions covered punishing distances — the equivalent of a marathon or longer. In many cities, the walks stretched more than fifty kilometres.

The Miles for Millions walk was not meant to be easy nor to be shoehorned into busy schedules. It required the commitment of a full day of walking in addition to many hours spent canvassing prior to walk day and collecting funds afterward. Yet it was deeply compelling to a generation of young Canadians coming of age in the late 1960s.

Charitable work with an international focus had long been a feature of Canadian youth organizations. Beginning in World War I and continuing through the Second World War, religiously affiliated youth groups and non-denominational organizations such as 4-H, Girl Guides and Boy Scouts, Canadian Girls in Training, Junior Red Cross, and YM/YWCA proliferated.

Schools also got involved. In the postwar period students were mobilized to raise funds for various foreign causes. For instance, in 1955, the first UNICEF Halloween drive took place in Canada, with costumed children going door to door with collection boxes around their necks.

The Miles for Millions walkathon marked a consolidation, expansion, and updating of earlier fundraising practices. The organizers used language and symbols that spoke to the rising generation, calling on them to use their “sole power” and declaring the walk a “rebellion against poverty around the world.” The slogans were often very earnest: “You walked — that others may live” and “Feet against Famine.”

The central message connected young Canadians’ actions to those of youth around the world. In Sweden, for example, youth had effectively pressured their government to set aside one per cent of the country’s wealth for international development. In an era in which we were reminded daily about our “global village” existence, the Miles for Millions walkathon became an important mechanism for consciousness-raising and activism around international crises.

Press coverage of the Miles for Millions walks across the country emphasized their youthful character, with newspapers reporting that young people “marched, limped, and sang by twos, fives, and twenties.” Oxfam Canada claimed that up to eighty percent of participants in the early years were high school students. The walkathon appears to have drawn boys and girls equally and to have represented the cultural and racial communities in which it was held. Working-class and very privileged students walked side by side.

The walkathon was not easy. Nicknamed “Band-Aid and bunion day,” its short-lived newspaper was aptly called The Blister. The Globe and Mail report on the 1968 walk described young people looking “like thousands of wartime refugees ... as they trudged mile after mile, grim determination and the hint of pain cast on their faces.” Reporting on the 1972 walk, the newspaper told of how a “pale, slim” fifteen-year-old girl walked from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. to finish the forty-four-kilometre march in Toronto. Her father was seen wheelchairing her in tears from the final checkpoint at city hall. Two girls collapsed.

A year earlier, a parent whose eleven-year-old daughter walked from morning until midnight described the frightening scene at Toronto city hall: “Parents carrying their children ... children and teenagers collapsed everywhere ... children lying on stretchers.”

Why did this endurance test have such appeal? The answer is complex. One factor was that organizers effectively used the schools to generate knowledge about and empathy for victims of world hunger. Sponsor sheets were distributed in classrooms. Students likely felt considerable pressure to conform, to join a good cause. There was also the added incentive of ribbons and certificates for those who finished the walk.

In the lead up to walk day, schools received Oxfam educational kits consisting of film strips, posters, simulation games, and the like to raise awareness about Third World need.

These materials juxtaposed Canadian children’s plenty with the needs of the world’s “hungry half.” Images of suffering children with distended bellies, skeletal frames, and pleading eyes adorned classrooms across the country.

These profound images simplified global issues into a basic dichotomy: The developing world child represented the Third World’s need and the Canadian child symbolized the able-bodied global helpmate. This led some Canadian youth to critique the wastefulness of the developed world. During the 1968 walk, a banner carried by young milers in Calgary depicted Canada as a hot-dog-eating child and Biafra as a starving waif.

The ubiquitous images of starving Third World children undoubtedly stimulated emotions ranging from empathy to guilt, but they also helped to engender a consciousness among Canadian youth of their own ability to help.

Eleven-year-old Katherine Huntley wrote in a 1971 letter to the editor of the Globe and Mail that kids went on the walk because they wanted to and said “everybody felt good because they knew they were walking for people who can’t.”

They didn’t need to know about the complexities of world food systems and of war and famine in far-off places; they were told that if they committed to a heroic feat of their own they could do something to stop the suffering. Walking all day seemed to Canadian youth a straightforward expression of empathy and activism.

It’s worth remembering that for much of the 1950s and 1960s, street demonstrations featuring youth were not always welcome. Young people were under heavy scrutiny. Many adults saw them as either mindless protestors or apathetic students concerned only with money and consumption.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

The successful fundraising efforts made on walk day countered such prejudice. The Miles For Millions promotional material urged young people to show adults what they were made of: “It’s a chance to show adults that teenagers aren’t lazy or irresponsible, and a personal chance to prove that to oneself.”

It was in fact difficult to criticize young people who were marching on behalf of humanity. Following walk days the media touted teenagers as heroes.

From the Globe in May of 1969: “They were skinny and fat, tall and short. They wore long hair and crewcuts, outlandish mod clothes and the trim uniforms of private schools. But in their mass display of guts and goodwill the kids showed there is little wrong with their generation.”

Globe columnist Richard J. Needham went a little deeper about “the problem of kids today.” Spouting the line that teenagers were “softer” than they used to be, he argued that kids don’t want to be soft but, unfortunately, “the over-protective homes and schools of an affluent society discourage kids, or actively prevent them, from making tests of their courage, their strength, their initiative, their personal commitment to some cause which excites them.”

Being so young, I didn’t walk very far. Yet for me it wasn’t about crossing the finish line; it was about doing something out of the ordinary in the name of others.

The enthusiasm for the early Miles for Millions events faded in the latter half of the 1970s as the novelty wore off. The campaign faced competition from other fundraising events — Vancouver alone held a thousand different fundraising walks in 1977. Danceathons, bikeathons, and the like also siphoned away support. By the early 1980s, Miles for Millions was done.

The pennies raised each year did not, in the end, result in the eradication of global hunger and poverty. But, for many of us, the experience opened our eyes to global injustice and convinced us, perhaps naively, that we could change the world with small gestures.

In the late 1960s hope abounded that Canada and international development could right the wrongs of the world. In the words of Lester B. Pearson, the prime minister who led the first Miles for Millions Walk: “If we can get the youth of Canada to stir up opinion, to point out that we have these obligations to our fellowmen [sic] who are not as well off as we, if we do that, then we will have made our contribution to the development of peace and security in the world.” Many young people took seriously this calling.

One of them was me. I wasn’t yet ten years old when I went on the walk. Even at that age I was troubled by the suffering of far-off children portrayed in walk posters and I was moved by the marvel of joining that great parade of humanity on walk day. I wonder how many of us first learned about global injustice and collective action as school kids on walk day.

Of course, being so young, I didn’t walk very far. Yet for me it wasn’t about crossing the finish line; it was about doing something out of the ordinary in the name of others.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement