7 Historic Objects

From everyday objects spring countless stories of Canada’s past. For decades, Parks Canada has preserved and protected artifacts that together reflect the material heritage of our National Historic Sites, National Parks, and National Marine Conservation areas.

The collection consists of approximately thirty-one milllion objects — including seven hundred thousand historic items and thirty million archaeological artifacts — reflecting more than eleven thousand years of history.

The objects, from fine art and furniture to industrial machinery, are occasionally loaned to museums across the country; many are on permanent display at Parks Canada places. A number of the objects will also be exhibited during the sesquicentennial at institutions such as the Canadian Museum of History and the National Gallery of Canada.

The following objects are just a small sampling of what is one of the largest and most significant collections of artifacts in Canada.

Proposed Flag

For nearly a century after Confederation, Canada had no official flag of its own. During that time, the Canadian Red Ensign, generally seen as the de facto flag, vied with the Royal Union flag (Union Jack) as the representative banner for the nation.

In 1925, and again in 1946, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King launched parliamentary committees to consider the creation of a national flag, but they both proved unsuccessful. Of the 2,409 designs submitted to the 1946 committee, sixty-seven per cent featured maple leaves, and sixteen per cent incorporated the Union Jack.

Other popular features included stars, fleurs-de-lys, the crown, and (of course) beavers. Seen here is one of the proposed flags from the 1946 debate. It is one of four flags that are part of the extensive Mackenzie King collection at Laurier House National Historic Site. The designer is not known.

Men’s Leather Shoe

In 1760, during the Seven Years War (1756–63), a fleet of six French supply ships were attacked by the British Navy while sailing on the Restigouche River that divides New Brunswick and Quebec. Among the French ships’ cargo were 5,500 pairs of shoes. During the battle, the British sank the French ships, including the frigate Le Machault.

In the 1970s, Parks Canada divers discovered the wreck of Le Machault and recovered several artifacts, including the shoe shown above. The site of the clash was designated the Battle of the Restigouche National Historic Site.

The Seven Years War was fought in Europe, India, and America, and at sea. In North America, Britain and France struggled for supremacy. In 1758, the British captured the Fortress of Louisbourg, followed by Quebec City in 1759 and Montreal in 1760. France formally ceded New France to Britain with the Treaty of Paris in 1763.

Transformation Mask

Transformation masks like the one depicted here are worn during ceremonies. The masks manifest transformation, often an animal changing into a mythical being or, in this case, the sun and the moon.

This mask, from the late-nineteenth century, is part of the Yuquot Collection of artifacts. The collection was assembled from the late 1960s to the 1970s. The Yuquot Collection was the direct result of a co-development plan between Parks Canada and the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation to build an interpretation centre at Yuquot National Historic Site, on the west coast of Vancouver Island. Although the co-development plan was never realized, this exceptional collection remains within Parks Canada’s care.

The Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation continue to plan the development of an interpretive centre. Once the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation’s interpretation centre is completed, the artifacts will be transferred back into their care at Yuquot.

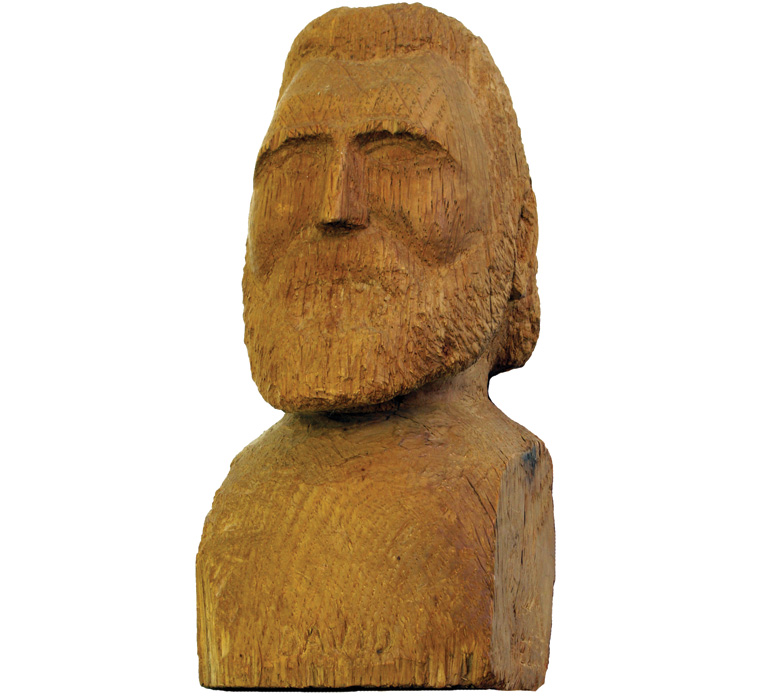

Riel Bust

William Henry Jackson (1861–1952), who later adopted the name Honoré Joseph Jaxon, left behind what is perhaps one of the most evocative representations of Louis Riel.

Jackson, a prominent labour organizer and best known for being Riel’s secretary during the 1885 resistance, saw himself as a “peacemaker between the Aboriginal and immigrant population of the North West.” Both Jackson and Riel were imprisoned following the Battle of Batoche in May 1885.

At trial, Jackson had hoped to defend Riel’s actions. However, the trial lasted a mere hour, as both the Crown and defence declared Jackson insane. He was sent to the insane asylum at Lower Fort Garry, located just north of Winnipeg. Riel was held in Regina, where he was publically executed on November 16, 1885.

During his time at the asylum, Jackson carved a small wooden bust of Riel. Measuring some 21 centimetres in height, the bearded face depicts a gaunt-looking Riel — reminiscent of a Christ figure — with the letters DAVID (Riel’s middle name) carved below.

Jackson presented the bust to Dr. David Young at the hospital on October 17, 1885, and fled shortly after. Lieutenant Colonel R.H. Young, the son of David Young, donated the bust to Lower Fort Garry National Historic Site in 1964, where it can still be seen today.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Pharmaceutical Bottle

In 1845, explorer Sir John Franklin set sail from England with two ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, in search of a Northwest Passage. The ships and crews vanished. Almost 170 years would pass until an expedition led by Parks Canada in 2014 discovered the wreck of Erebus.

This glass bottle is just one of the artifacts recovered from the site, recognized today as the Wrecks of the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror National Historic Site in Nunavut. This small glass medicine bottle is marked “Samuel Oxley” and “London.” Oxley was a London chemist who sold “Concentrated essence of Jamaican ginger root,” a compound claiming to cure a variety of ailments from digestive complaints to hypochondria. On board HMS Erebus, it may have been a popular seasickness treatment.

This bottle actually had nineteen lead birdshot pellets inside, suggesting that it was reused as a shot flask. Detailed content analysis also found traces of gum arabic and potassium bicarbonate, both of which were carried in every standard nineteenth-century Royal Navy medicine chest. Reuse of containers was frequent during that time period, but to find such clear evidence of multiple use of the same object is quite remarkable.

Peace Treaty Wampum Belt

Wampum are traditional shell beads of the eastern woodlands First Nations of North America. The white beads were made from whelk shells; dark purple beads came from quahog, a hard-shelled clam. Both were found along the shores of the Atlantic seacoast.

Wampum were made into belts that functioned as mnemonic devices for communication. They were instruments of spiritual and political life. Each belt represented a particular event — a single talk, a council, or a treaty. The contrast between the dark and light shells made patterns that had meanings, and their interpretation was an important task.

The wampum keeper kept the wampum of his people, bringing it out when required. Belts were also exchanged as a form of treaty. If a quarrel arose between two parties who had exchanged belts, the wampum keeper would bring out the appropriate one and recite the terms of the original treaty.

This wampum belt was acquired by Parks Canada in the early 1970s. It is thought to be associated with the 1701 Great Peace of Montreal between New France and nearly forty First Nations and is part of the collection of Fort Chambly National Historic Site in Quebec.

Robert Service’s Typewriter

Robert Service (1874–1958), the “Bard of the Yukon,” was one of the most adored and commercially successful poets of the twentieth century. He was born in Preston, England, and arrived in Canada in 1896 at the age of twenty-two. He travelled extensively, principally along the west coasts of Canada and the United States.

In 1903, he started working for the Canadian Bank of Commerce in British Columbia. In 1905, he was sent to Whitehorse in Yukon Territory. During his years in the Yukon he produced The Spell of the Yukon, Ballads of a Cheechako, The Cremation of Sam McGee, and other literary works. After moving to Dawson City, Service wrote some of his most memorable works on this 1901 Bennett typewriter in a tiny cabin on Eighth Avenue, where he lived from 1908 to 1912.

His home, a part of Dawson Historical Complex National Historic Site, can be visited as he left it in 1912, and his typewriter is part of the cabin’s collection of historic objects.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement