Building a Kinder Country

Canadians today enjoy many rights and freedoms. But it wasn’t always this way.

For much of Canada’s history, the country was split along social, racial, economic, and gender-based fault lines. Few women could hold property, and most couldn’t vote. Indigenous people were marginalized in myriad ways, and laws that banned immigration from “non-white” nations, especially from Asia, remained in place until the middle of the twentieth century.

The social progress we take for granted today was achieved by average Canadians who stood up for what they believed in. Here are just a few places where Canadians demanded justice, welcomed the less fortunate, and took steps — and, sometimes, missteps — along the road to a greater, more caring country.

Walker Theatre

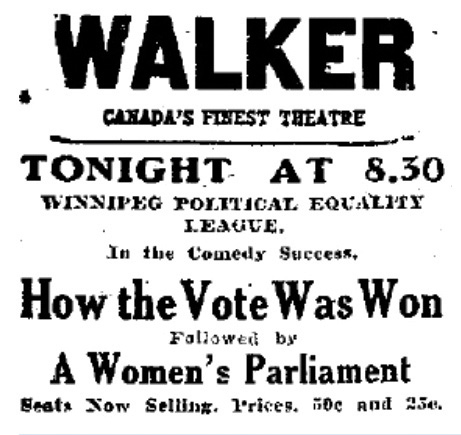

In Winnipeg, winter is always cold, but on January 28, 1914, Manitoba’s premier certainly felt the heat — thanks to 1,800 people who gathered at the Walker Theatre to watch a “mock parliament.”

The “star” of the show was Premier Rodmond Roblin, as played by the prominent suffragist and writer Nellie McClung. Inspired by a similar mock parliament held earlier in British Columbia, the goal was to lampoon the province’s unreasonable rationale for preventing women from voting. Roblin’s Conservative government used all the typical arguments: voting would cause strife at home; women were too pure to be dragged into the muddy world of politics; etcetera. As Roblin infamously said, “Nice women don’t want the vote.”

During the mock parliament, the women turned the tables on the men, questioning whether they were smart enough to understand politics. As a rebuke to the constant attacks by men on the appearance of suffragists, the women debated whether “ugly” men’s clothing — such as “scarlet neckties, six-inch-collars, and squeaky shoes” — should be banned.

McClung stole the show with her send-up of the blowhard Roblin. Looking back, the mock parliament was a key moment in the long battle for gender equality in Canada. Two years later, to the day, Manitoban women became the first in Canada to win the right to vote in provincial elections.

Grosse Île and the Irish Memorial

During the nineteenth century, waves of Irish left their homeland to start new lives in North America. Many were forced to move by the Irish famine of the mid-nineteenth century.

The journey by sea was long and arduous, and many passengers fell ill with cholera, typhus and other illnesses.

rriving at the St. Lawrence River, if illness was discovered aboard, passengers disembarked at a lonely rock outcropping near Quebec City — Grosse Île. There, thousands of passengers, including many Irish, were quarantined, and many died. During the century the site was in operation, more than half a million immigrants were processed there.

Today, visitors can explore the many buildings and facilities that date back to the island’s painful past. They can also view the cemeteries, the quarantine station, and the Celtic cross and memorial for the more than five thousand immigrants who died while in quarantine at Grosse Île, and to all the others who were buried on the island. This National Historic Site is a stark reminder of the price many people paid for their desire to settle in Canada.

Batoche

For four days during May of 1885, the Métis resistance led by Louis Riel was able to hold off the military power of the Canadian government.

Three hundred Métis and First Nations fighters faced down eight hundred soldiers of the North West Field Force. But wars are not won with willpower alone. As their ammunition dwindled, so did the Métis’s chances of achieving victory at the Battle of Batoche.

The fighting, which started on May 9, ended on May 12. Riel surrendered three days later.

The Battle of Batoche was the culmination of a much longer struggle for Métis and First Nations to secure their rights to both land and self governance.

In 1870, the intrusion of the Canadian government at the Red River Colony (in modern-day Winnipeg) compelled Riel to declare a provisional government.

That fight ultimately resulted in Manitoba entering Confederation as the fifth province of Canada. But Riel was forced into exile in the United States.

In November of 1885, Riel was hanged — the same month that CPR chief Donald A. Smith drove the last spike in the transcontinental railway. As the country was united by steel rails and wooden ties, it was also being driven apart by the execution of a man whom many today consider to be a Father of Confederation.

Nikkei Internment Memorial Centre

Non-whites had always faced prejudice in early Canada. On the West Coast, people of Asian descent faced especially overt societal and legal discrimination, as both governments and average citizens feared a perceived “yellow peril.”

Despite these hurdles, immigrants from Asia persisted to build lives for themselves and their families. By the 1940s, thousands of Japanese newcomers were living in British Columbia, mostly along the coast.

In December 1941, prejudice turned to hostility in the wake of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

Almost immediately, all Japanese Canadians were declared a potential security threat. Claiming they were acting in the national interest, authorities rounded up more than twenty-two thousand Japanese Canadians and forced them to move to internment camps in the interior of B.C. In many cases, authorities seized the property of Japanese Canadians and sold it off.

Today, this dark stain on Canada’s past can be explored at the Nikkei Internment Memorial Centre, on the shores of Slocan Lake at New Denver, British Columbia. Declared a National Historic Site in 2007, the Nikkei camp was built by the British Columbia Security Commission in 1942. Today it is one of the few internment camps that remain standing in Canada. The site is a reminder of the consequences of wartime fears and the need to remain vigilant in the defence of civil liberties for all Canadians.

Salem Chapel British Methodist Episcopal Church

This modest church was the spiritual home to one of the Underground Railroad’s most famous personalities — Harriet Tubman.

Built in 1855, it was an important centre of nineteenth-century abolitionist and civil rights activity in Canada.

Most escaped slaves came to Canada via the Underground Railroad, a series of safe houses run by abolitionists. Many of the former slaves settled in southern Ontario. In 1788, a group of black settlers arrived in St. Catharines, and by 1814, they had established a chapel in the community. In 1850, the U.S. Fugitive Slave Act demanded that escaped slaves be returned to their “rightful” owners. In response, more escaped slaves fled the northern states to Canada, where slavery had been banned since 1833.

At St. Catharines, the congregation decided that a larger church was needed to serve the growing black community. Construction began on the United Salem Chapel British Methodist Episcopal Church in 1853 and was completed in 1855. The church quickly became a central gathering place and base of operations for abolitionists, including Tubman, who lived in St. Catharines between 1851 and 1861. Many of the escaped slaves she assisted settled in the St. Catharines area.

The United Salem chapel, named a National Historic Site in 2000, remains a reminder of the generosity of the human spirit.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Help support history teachers across Canada!

By donating your unused Aeroplan points to Canada’s History Society, you help us provide teachers with crucial resources by offsetting the cost of running our education and awards programs.