Home Truth

The latest in transatlantic travel brought my grandfather from Westminster, U.K., to Canada at the beginning of the twentieth century; my own voyage began with the latest in transatlantic technology at the end of twentieth century.

I suspect we shared the same wonderment and anxiety as the worlds that we knew changed forever. His world was British and fashioned by poverty and deprivation; my world was Canadian and built on some kind of notion of at least partial Gallic roots, ones that had shaped my scholarly and personal life.

Then in a brief, electronic moment in the summer of 1999, both our worlds changed forever, as his future became my past.

“I have finally tracked you down.”

This short email message that I received on August 9, 1999 — although I did not know it at the time — altered my view of myself and my place in this world. It continued:

“I am a De Brou from England: I’d appreciate any info on any common ancestry. If you reply, then I’ll email you my family history and some details of speculation that we have made. Thanks, Austin De Brou.”

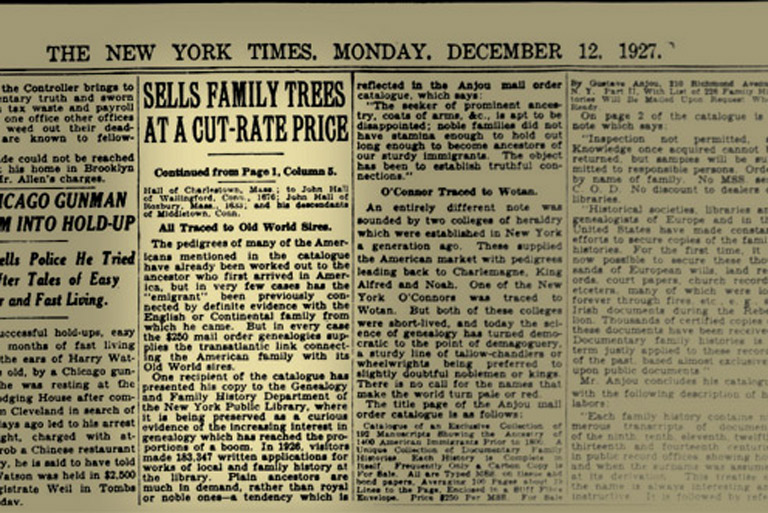

I was intrigued but viewed the message routinely. I had indulged in the Internet roots game myself but had received no responses from the few website authors that my Internet search engines had uncovered.

The one exception came from a De Brou in Belgium who had responded kindly to my query hut had said that she had never heard any talk about relations in Canada so she suspected that there were no connections between our two families. That bad been in August 1996.

I doubted De Brous had English roots. I had heard my maternal grandfather describe my grandfather De Brou as “the little Frenchman.”Thus, I had always assumed my roots lay either in Quebec, France, or Belgium.

Besides, my grandfather De Brou had married an Aimée Blondin, supposedly the granddaughter of the great Charles Blondin, the tightrope-walking Frenchman who had conquered Niagara Falls.

Thus, family lore repeated that while my maternal side was Irish, my paternal side was French. That, along with the fact that I spent the first seven years of my life in the Montreal area, had shaped the road I would take as a university student and eventually as a scholar.

Driven, I think, by a natural interest in the past (at ages twelve and thirteen my favourite books had historical settings) and an almost guilty feeling that French was not my maternal tongue, I saw myself, perhaps unconsciously, as a kind of scholarly knight who would restore honour to the family’s French name.

Advertisement

At university as a history major. I gravitated toward Canadian essay topics that forced me to read in French. I also took a couple of French-language courses, no matter how difficult they were for me.

After I graduated with my three-year history degree in the fall of 1972, I travelled in France for three months. In the winter of 1973–74, I lived within the old part of Quebec City, going daily to an ancient church building that housed the library of the Institut Canadien.

There I read the historical work of the famous Abbe Groulx. In time, I made my way to the history department of the University of Ottawa, which welcomed my interest in Quebec history and my attempts at becoming bilingual. I look most of my graduate courses in French, but found the required extra hours invigorating.

I was on a mission.

Even my personal life had a French twist. Half my friends were French: some truly bilingual, others more comfortable in French. For a short two-year interlude, I was even a French elementary teacher.

Unable to slake my thirst for Quebec history, I returned to do my PhD with the well-known professeur Fernand Ouellet. At Ottawa, I met my future wife, who had “come back” to Canada where her French roots in Quebec dated to the sixteenth century.

Originally from New Hampshire, my wife’s family only viewed Canada through the eyes of its Quebec aunts, uncles, and cousins.

Indeed, on my first visit to my future in-laws, one of my wife’s American nieces asked me in a loud, deliberate voice so that I would understand her: “Do you speak English?”

I celebrated. I had partially achieved my goal.

From this perspective, I viewed Austin De Brou’s I’ve-tracked-you-down electronic message. I replied perfunctorily on that same day in August:

“Finally someone else looking for the De Brou clan. Not much info at this end. I am one of five children whose father James Francis De Brou (1928–1958) was the single offspring of my grandfather James Francis De Brou (1900?–1950s?). As you can see, not much to go on — my grandfather De Brou from the 1920s to his death lived in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, but before that I am not sure. My grandfather on my mother’s side described him as the little French man.”

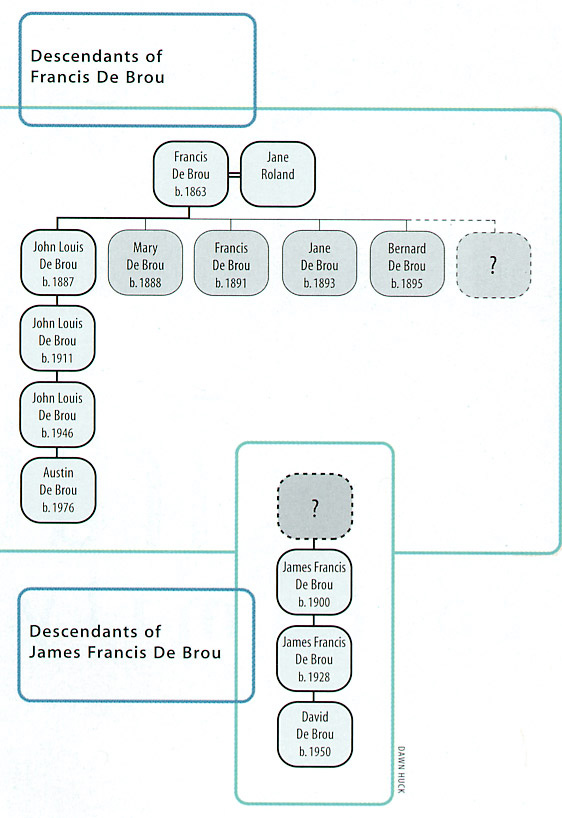

Austin De Brou’s response was in the form of a family-tree document which contained lots of De Brou names that I did not recognize — a few John Louis, a Mike, an Annie, a Jane, and a Louisa.

I noted a James and a Frank, but in the end told Austin two weeks later that I had “very little information re: the De Brous in Canada — a single son of a single son and both deceased since the 1950s.”

Although I was intrigued by Austin’s emails, I did not really have much to offer since all of my relatives who might know something were no longer alive (my father died in 1958, my mother in 1987, and my maternal grandfather in 1994).

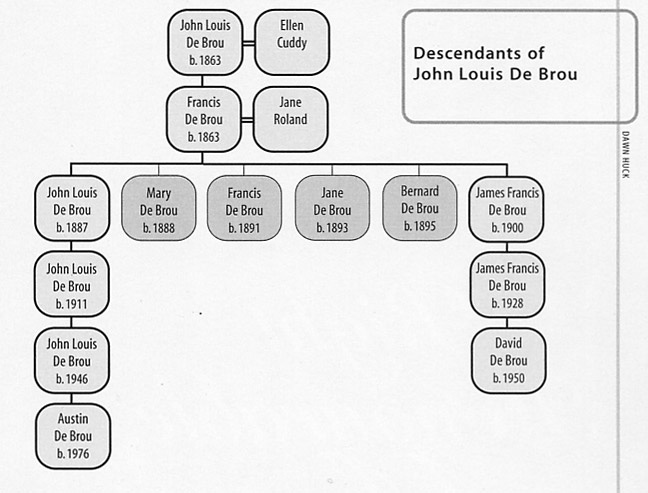

The most fascinating elements of Austin’s family tree were the children of Francis De Brou (born 1863) and Jane Boland; this generation was born in the same era as my grandfather.

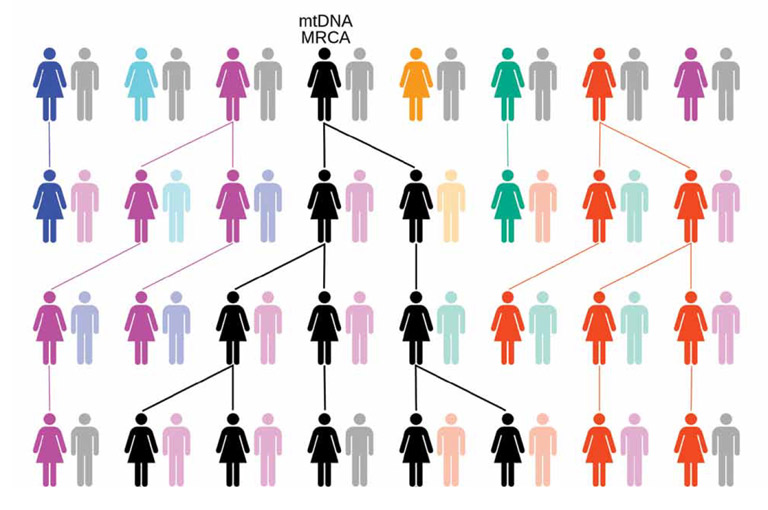

Furthermore, Francis was a common reoccurring name among the U.K. De Brous, the same name that found favour in three generations of the Canadian De Brous (see chart to the left). Both my father and grandfather shared Francis as a middle name, while my parents named my only sister Frances.

Another genealogical phenomenon that both set of families shared was the propensity to pass on family first names to the next generation.

For the Canadian De Brous it was James Francis; for the U.K. De Brous it was John Louis and Francis. These observations finally convinced Austin and me that perhaps we had more in common than late-night Internet travelling.

In an email in mid-October 1999. Austin’s growing excitement was evident:

“Arrgh! I’ve just read what you wrote some time ago! The second Francis here was born in 1891. This makes him contemporary with your grandfather James Francis De Brou. Further he had a brother John Louis who after using the names of his father, Francis, his own name, and that of his sister, called his other son James. I find this a somewhat marked coincidence, and begin to wonder if maybe there isn’t the slightest whiff of a connection. This could make you — my second cousin once removed?”

My response was equally enthusiastic. That same day I reported to Austin: “I think things are heating up here. If I read your message correctly, we may share the same great-grandfather.’’

But even though it was beginning to feel right, we still needed documentation to support our speculations.

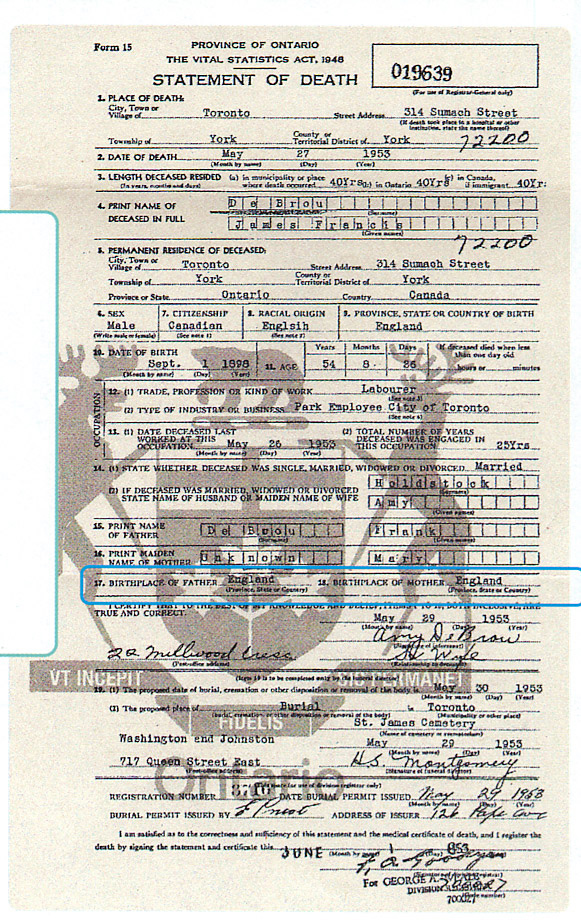

Inspired by Austin, a twenty-four-year-old with the genealogical bug, I decided to spend some money and time to see if my grandfather had any kind of official record in Canada. I did not know the exact year of his birth or death, but remembered with the help of my older brother that my grandfather had died in the 1950s in his fifties.

One month later, I had in my hands my grandfather’s statement of death. The document astonished me in two ways.

First, it confirmed that my grandfather, “the little Frenchman” was indeed horn in England and that he had immigrated to Canada forty years earlier (1913).

Second, my so-called French Quebec grandmother Aimée Blondin was also born in England; more stunning was the news that her name was Amy Holdstock. Suddenly, my grande-maman had become my Nana.

But what of my connection to Austin De Brou? My grandfather’s statement of death provided information that placed the Canadian De Brous in the U.K., but it seemed to lessen the possibility of a direct Austin-Dave link. Austin had discovered that his great-great-grandfather, Francis De Brou (b. 1863), was married to Jane Boland; the parents of my grandfather, James Francis De Brou, according to the statement of death, were Frank De Brou and Mary, with her maiden name unknown. Both Austin and I were disappointed. But like good family detectives we tried to consider all possibilities.

I pointed out in my email to Austin that the validity of this information, as reported in the death certificate, depended on the information provided by my grandfather’s wife Amy De Brou. How much she really knew about my grandfather was not clear to me, since they had been estranged for a number of years.

The statement of death indicated that my two grandparents were no longer living at the same address at the time of his death. With more experience in the genealogical game, Austin endeavoured to integrate my grandfathers reported parentage of Frank and Mary.

He wrote; “Okay, I’m wondering if Frank could be Francis De Brou, b. 1863, father of my great-grandfather John Louis — b. 1887, of Francis — b. 1891 (Jnr for convenience!), and Jane —b. 1893, and Bernard —b. 1895. Now as far as I know. Francis (Senior) was married to a Jane Roland in 1887, and they were the parents of the above quartet, so we have four options: 1) No connection at all; increasingly this seems unlikely as names and dates start to correspond; 2) James Francis was a late addition and your relative [Amy Holdstock] was wrong about the name of his mother (Mary); 3) Francis Senior remarried or had a child by another woman; and 4) Frank was a relative of Francis — a cousin perhaps.”

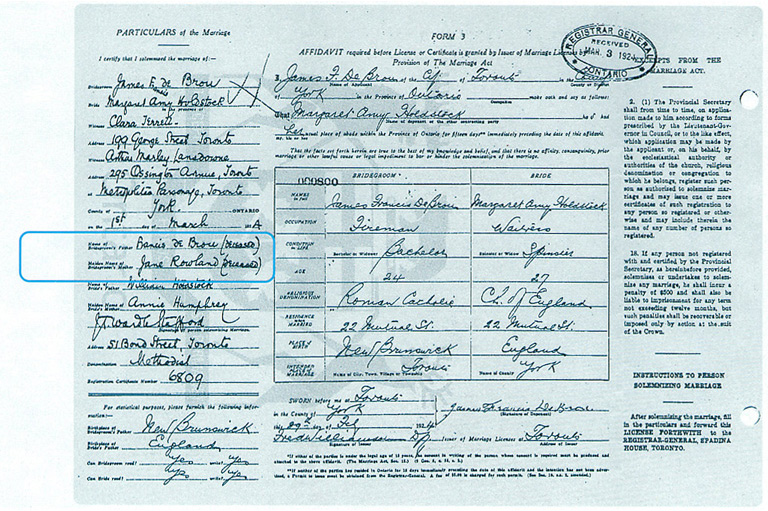

One month later, we had our answer — my grandparents’ marriage certificate. On March 1, 1924, twenty-four-year-old James Francis De Brou — bachelor, fireman, and Roman Catholic — and twenty-seven-year-old Margaret Amy Holdstock — spinster, waitress, and Anglican — exchanged marriage vows in Toronto, Ontario.

Interesting stuff, particularly James Francis’s age at the time of the ceremony, listed as twenty-four in 1924, suggesting that he was born in 1899 or 1900, not 1898 as indicated in the death certificate. More remarkable was the listed “particulars of the marriage,” which included the names of the bride’s and groom’s parents: for the bride, William Holdstock and Annie Humphrey; for the groom, Francis de Brou (deceased), and Jane Rowland (deceased).

Bingo! That’s what Austin and I had been waiting for. We had proof that my great-grandparents and Austin’s great-great-grandparents were the same two people: Francis De Brou and Jane Ro[w]land.

Yet, the details of the “marriage particulars,” while providing the essential transatlantic link for the two De Brou families, muddied the genealogical waters. Not only had the marriage licence taken one or two years from James Francis’s young life, but contrary to the statement of death, it pronounced the birthplace of James Francis and his father Francis to be, not England, but New Brunswick, Canada.

As a good historian, I endeavoured to explain the conflicting information. Noting that the source of marriage information was likely the groom himself, I attempted an explanation in an email to two of my brothers:

“This New Brunswick birthplace is interesting. Remember that James Francis was bom in 1898, 1899, or 1900: that means he could have been conscripted in the army [British or Canadian] in the 1916–1918 period. I wondered if he changed his birth date and birthplace to avoid being conscripted. Just a thought — you know how devious the De Brous can be.”

I was not convinced of this argument. Indeed, many young Canadian men who had emigrated from the United Kingdom in the decade prior to 1914 were among the first to volunteer for the Canadian Expeditionary Force, which eventually found itself in the blood-soaked trenches of France and Belgium.

Austin De Brou’s next message revealed another possibility, one whose origins may also lie with the First World War I. According to Austin, my grandfather’s brother John Louis De Brou (born in 1887) “was very ill and spent a period of time in hospitals and infirmaries after WWI.”

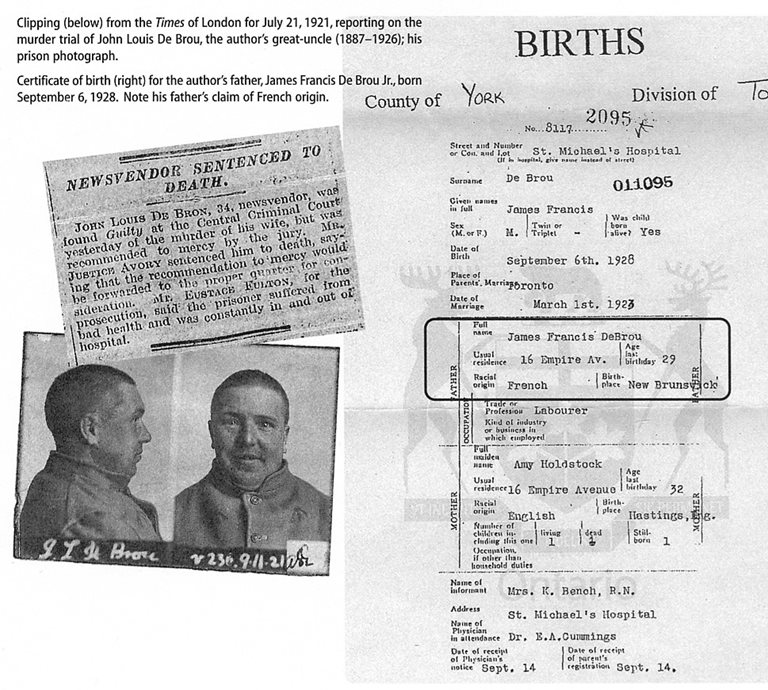

We do not know yet whether the precariousness of my great-uncle John Louis’s physical and mental state was rooted in military service, but the events that took place one night in 1921 were tragic. That evening he came home and his alcoholic wife threatened him.

Austin continued the grim story: “Apparently he lashed out with a razor, which was laying nearby, and then ran out into the street to the police station in a dazed state to beg the police to help.”

The police rushed to the house and found my great-aunt Annie dead in the bedroom: asleep in the same room were their five children, the youngest covered in the blood of their mother. My great-uncle “was tried at the Old Bailey [Central Criminal Court which included the London area] and sentenced to death, although the jury said that because of his long history of illness, his weakened state, and the fact of his wife’s alcoholism, he should not he executed.

The judge who forwarded his appeal to the Home Secretary said that he had had no choice but to pass the death sentence but that the Secretary should note the jury’s plea for mercy.”

Eventually the home secretary commuted his sentence to life imprisonment; my great-uncle died of heart disease in 1926. Perhaps this tragedy in 1921 was the explanation for my grandfather’s statement at the time of his marriage that both he and his father were natives of New Brunswick.

I speculated that reports of the De Brou murder had reached Canada and my grandfather’s reaction was to disown his family in the United Kingdom. Perhaps he responded to the painful questions with, “Oh, no. I have no relatives in London. My father and I are French, and we were born in New Brunswick.”

To confirm my suspicions, I searched the Toronto papers of that era for any news from London of the murderous calamity. I did not find any reports, leaving my suggestion as speculative.

In fact, a copy of my father’s statement of birth that I received in February 2000 again claimed Canadian origins for my grandfather. To the reporting nurse, my grandfather described himself as French and born in New Brunswick.

For the rest of the year, Austin and I were left pondering the transatlantic break between our families. Austin provided additional information about the difficult circumstances in which the United Kingdom De Brous found themselves during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Apparently, Francis’s mother Ellen was as destitute as her husband, another John Louis De Brou, who was a commercial traveller not residing with his family at the time. From workhouse to selling flowers and newspapers in Piccadilly Circus, the De Brous of Westminster, it seems, were part of London’s urban poor.

Into this world, my grandfather, James Francis De Brou, was born on September 1, 1900. How my Westminster grandfather came to be in Canada remained a mystery until November 19, 2000.

That day I was showing my fourth-year history honours class the online databases available at the National Archives of Canada (see the online research tool ArchiviaNet [ed. note: it is now called Collections Canada hosted by Library and Archives Canada]).

To demonstrate the utility of the different primary sources, I asked the students to provide their family names for a search. No one had relatives who had volunteered for the Canadian Expeditionary Forces during World War I; no one had an ancestor who had immigrated to Canada between 1925 and 1935; and no one had a forebear who appeared in the 1871 federal census for Ontario.

Perhaps bitterness or shame caused my grandfather to hide his London birthplace all his life; only his death revealed a British past.

I then moved on to the next database — Home Children, the names of poor urban children sponsored by various British philanthropic groups and shipped from the United Kingdom to enjoy the relative healthy environment of Canada’s farming communities.

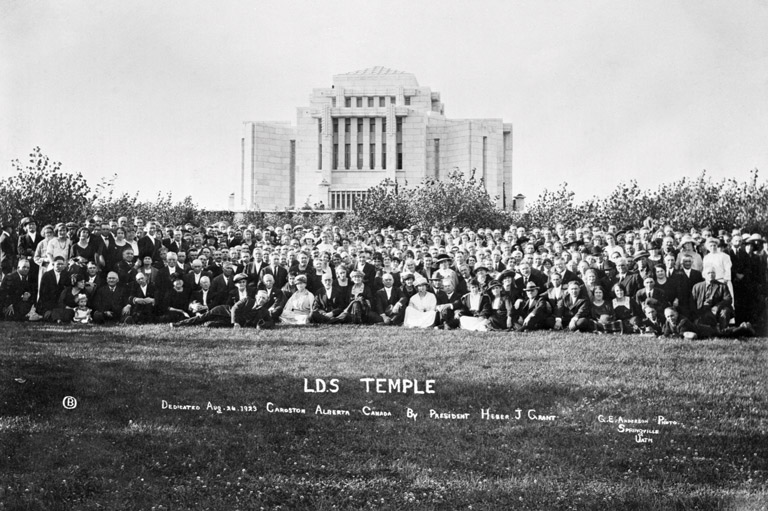

Since none of the students had family members that fell into that category, I typed in the name De Brou. I did a double take as the name of James Debrou appeared on the screen. Here was the answer for which we were searching: in 1912 a Roman Catholic organization deemed my grandfather an appropriate candidate for emigration to Canada.

Whether he was an orphan, the son of “unsuitable” parents, a street urchin, or a young delinquent is not yet clear. But the ship’s manifest reveals that on April 20, 1912, eleven-year-old James Debrou boarded the SS Tunisian, along with fifty other young Catholic boys under the care of Reverend Thomas Newsome.

Eight days later, my grandfather and the other 1,488 passengers landed at Halifax, Nova Scotia. The boys were scheduled to board an Ottawa-bound Canadian Pacific Railway train. From that point on, until his marriage in Toronto in 1924, my grandfather’s whereabouts remain a mystery.

Perhaps the documentary references to New Brunswick are a clue to his eventual destination. Or did he travel with the rest of his Catholic companions to Ottawa?

Was he going to St. George’s Home to be farmed out to a local family in the Ottawa Valley? Was he one of the fortunate children whose Canadian “family” treated him fairly? Or was he one of the many who faced hardship and sorrow, scorned by Canadian hosts as London gutter children?

Conceivably, herein lies the answer to the riddle of my grandfather’s origins.

He reported his birthplace as New Brunswick, let my maternal grandfather think he was “a little Frenchman,” and did not tell my father that he was a home child from London because of the painful memories caused by the separation from his family in England and the cold reception he had received in Canada. Perhaps bitterness or shame caused him to hide his London birthplace all his life; only his death revealed his British past.

My older brother, when he found out that our French roots were minuscule, was amused. He pointed out to me with pleasure that “the big specialist in Quebec history had little French in him.” My feelings are more circumspect.

Yes, the recent revelations had diminished my “Frenchness,” but the stories of my “French” grandparents had had a direct impact on my life. Certainly my interest in Quebec history, which derived in part from this false family heritage, eventually led me to the University of Ottawa and my future Franco-American wife, and had also taken me to the University of Saskatchewan where I was hired as a Quebec specialist.

The transatlantic voyage aboard the SS Tunisian that my grandfather, James Francis De Brou from Westminster, U.K., had embarked on in 1912 eventually led me to Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

My trip back to Westminster began that momentous day in August 1999 when my cousin Austin used the latest in technological communications to “finally track me down.” in that one electronic micro-moment, my life in late-twentieth-century Canada spanned time and distance to reconnect with my grandfather’s world in early-twentieth-century Britain.

The Little Immigrants

One day in 1909, a British children’s home took six children from a woman in London whose husband had deserted her. The children were separated. Five years later, fifteen-year-old Joseph Lorente was sent to Canada.

Sitting in the railway station in Hull, Quebec, one day in 1937, Arthur Lorente heard a passerby say, “You’d better take it up with Joe Lorente.” Arthur leapt up and asked, in his Cockney accent, what this Joe Lorente looked like. Could it be his brother? The man thought it unlikely. “Joe doesn’t talk funny like you.”

But when Joe Lorente opened his door and saw the sailor holding a duffel bag, he knew immediately Arthur was his brother. Standing behind Joe was his son Dave, who would found an organization called Home Children Canada several decades later.

Between 1868 and 1925, philanthropic children’s homes sent about 100,000 children from Britain to Canada. They stayed in institutions in Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritimes before being sent to work as farm labourers and servants.

Some were as young as two. Only about a third were orphans; some had parents who could not afford them. Often, the philanthropists who ran the homes took children from parents they considered unsuitable or shipped children to Canada without their parents’ knowledge or consent.

For the British government, child emigration was a way to get rid of urban poor. For the Canadian government. it was a source of cheap labour and British immigrants. For the evangelists who ran many of the homes (such as Thomas J. Barnardo), it was a way to save the children from their parents and the temptations of the city.

“They did believe that hard work and open spaces would make for good citizens,” says Dave Lorente.

Joe Lorente experienced both sides of what home children found when they came to Canada. At his first assignment at a home outside Ottawa, he was threatened with a pitch-fork and ran away. Members of his second foster family were much kinder, and he remained friends with them for years.

Some home children were adopted, especially the youngest ones, but most were servants who were paid low wages. If the child was younger than ten, the home would usually send money for the child’s keep, although the child would still be expected to work.

As the child got older and was able to work more, the family would begin to pay meagre wages, although these were usually held back until the child left as an adult. For example, a boy from Barnardo’s home might receive a fee of somewhere between $100 and $200 when his indenture with a family was over.

Many of the boys were abused, and many of the girls were sent away after becoming pregnant by men on the farms where they worked.

“Most of [the children], including my father, never even spoke to their own children about it,” Dave Lorente says.

Many home children, growing up in an age when most people considered poverty and crime hereditary flaws, fell rejected by their parents and their country.

“They were looked upon as almost subhuman,” says John Sayers of the British Isles Family History Society of Greater Ottawa.

For seven years, Sayers has been compiling a database containing the names, ages, ships, and dates of home children. The Home Children Records can be accessed through the Library and Archives Canada website, which is where Dave Debrou found it.

The database is far from complete and far from perfect — the people who wrote the ship’s lists often took liberties with penmanship, spellings, and dates. Many of the children were malnourished and looked younger than they were, so the immigration agents guessed their ages incorrectly.

Privacy laws can also make it difficult for researchers such as Sayers to unearth records and correspondence. The agencies themselves saved few records and are not always willing or able to share them. But with the help of cross-references from immigration records and census data, Sayers continues to update the database.

Surviving home children are learning about their past, having reunions, and shaking the stigma. They and their descendants (which some sources estimate at more than three million people) are researching their family histories through traditional methods and a myriad of Internet resources. Dave Lorente answers about three thousand letters from descendants each year.

“It’s part of who you are, and whether it’s good or bad, it’s important to know it,” Lorente says.

— Kate Heartfield

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!