Roots: Blinkered Blunders

As newbie genealogists, we quickly learn that several clicks of the mouse grant entry to a hidden world where our ancestors live on in censuses, civil registrations, land records, historical newspapers, and more — all searchable by name. Fifteen new ancestors by bedtime? Not a problem.

These early experiences condition us to think that’s the way it’s always going to be. When we get bogged down, no biggie. We move to a different branch of the family. Problem is, we eventually run out of well-documented ancestral lines. Finding truly elusive relatives may require new research skills or trips to faraway repositories. Each discovery takes time and, often, money. Enthusiasm can wane.

Then there comes a rite of passage known to every experienced genealogist: the first full day of labour that yields not a single material discovery. For me, this happened at the National Archives in Kew, London, England. I had spent eight or nine hours combing through employment records of major nineteenth-century British railways, trying to nail down an apocryphal story about an ancestor who reportedly died on the job in a train accident in 1891. By day’s end I was no closer to knowing the identity of the man than when I’d started. And I was supposedly doing this for amusement and gratification, when I could have been enjoying London?

Advertisement

Yet we remain optimists. When we tackle a new problem, we never imagine it will take days, months, or even years to solve. No wonder we’re prone to impatience when reality sets in. The more impatient we become, the more susceptible we are to tunnel vision.

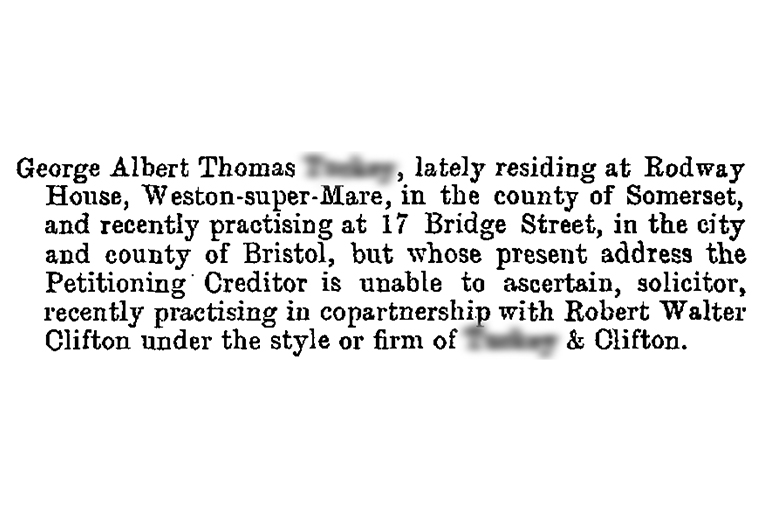

I often fail to extract every bit of intelligence from a document. I locate the fact that I’m looking for, and, in my keenness to move on, I don’t take the time to analyze other seemingly unimportant information on the page. If only archival documents came with annotations and highlights, such as: “The neighbours may be unexpectedly relevant,” or, “Have you considered why his entry visa starts with the letters QIV?”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The desire to get on with it also undermines our strategic decision-making: We don’t take the time to analyze the right way to tackle a problem. Long-time researchers, those who came to genealogy in the last millennium, sometimes give short shrift to DNA as a research tool. They’ve done the tests and looked at the results, but it’s not second nature to ask themselves with every new problem how genetic genealogy could lead to a quick solution.

In my case, it worked the other way round. Once, I confirmed the identity of an ancestor via genetic testing. When it came time to find his father, I spent months devising ever more intricate DNA analyses to home in on a leading suspect. All the while, I ignored fruitful documentary clues because of my knee-jerk fixation on DNA as the right approach.

You can be fixated on anything. They were German. Well, maybe they were Dutch. She was born in 1873. On the other hand, she wouldn’t have been the first to misrepresent her age. They just disappeared. Or maybe they simply emigrated.

These pleadings are all variations on the same refrain: I’m in too much of a rush to consider dispassionately which of my assumptions is holding me back.

Consider my great-grandfather. After 1891, he seemingly vanished. Yet all the time he was just five kilometres from where he had last been seen. He married, fathered several children, and died during the time period in which I was unsuccessfully looking for him. My incorrect fixation: All my other English West Country ancestors had lived in Dorset or Somerset. Why would my great-grandfather, born in Somerset, have been different? It seems he married a Wiltshire lass. Five. Kilometres. Away.

Yes, I’m an idiot, but I have plenty of company.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!