Kings of the New World

Tucked away in the vaults of Library and Archives Canada’s Portrait Gallery is a set of remarkable paintings that the Canadian public rarely gets a chance to see. Known as the “Four Indian Kings,” these full-length colour oil paintings of Indigenous men oddly dressed in capes and tunics will be seen in Canada in 2010, their first public showing in this country in more than twenty years.

Created in 1710 by an obscure Dutch artist while the Indigenous men were visiting London as diplomatic envoys, the paintings — and the story behind them — continue to fascinate us. Up until that time, North American Indigenous people who found themselves in Europe were usually there under duress — as curiosities at best, as slaves at worst. These “Indian Kings” were different — they were treated like people who wielded real power.

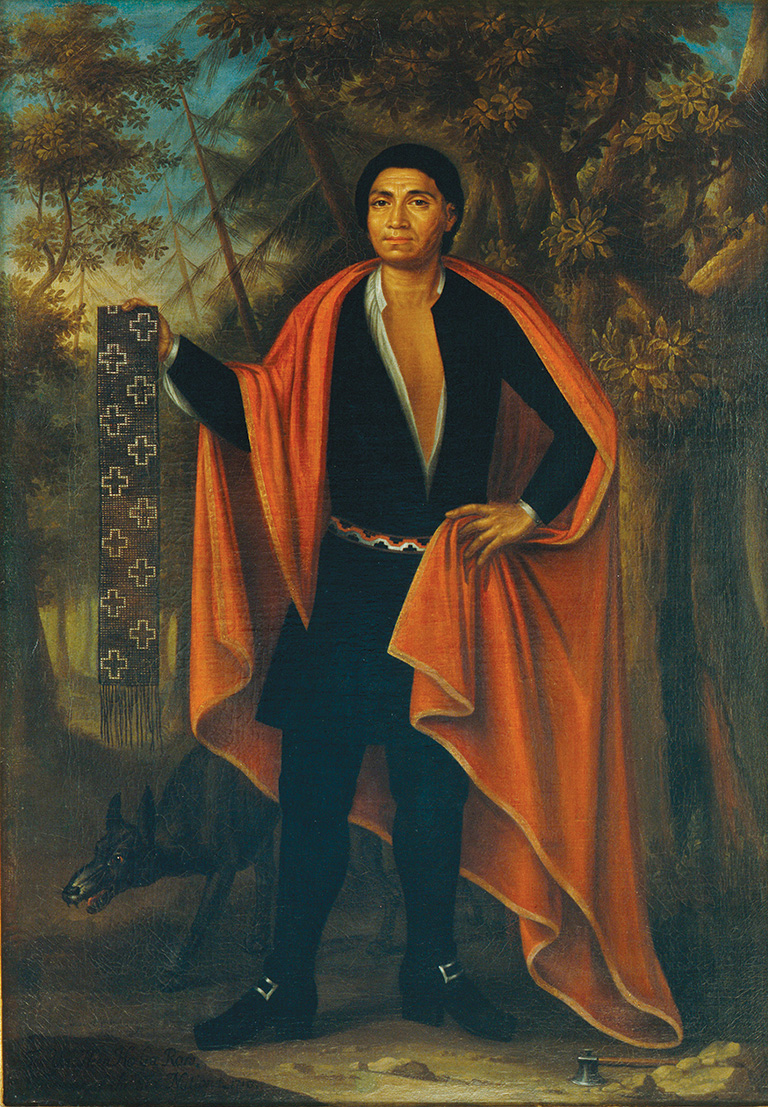

What everyone noticed about the men as they entered St. James’s Palace on April 19, 1710, was that they were exceptionally tall, strong, and in perfect health. Dressed in partial English fashion in freshly tailored waistcoats, breeches and stockings, with scarlet cloaks around their shoulders and buckled shoes on their feet, the four Indigenous leaders from the New World dwarfed their European hosts. The contrast between these “men of good presence,” as one observer of the time called them, and the ailing queen they had come to make entreaties of was especially jarring.

Queen Anne sat on her throne to receive the chiefs, which was just as well, since standing was almost impossible for her. Gout, obesity, and other health problems had left her essentially immobile. Besides feeling uncomfortable, she was unhappy. She was a widow at forty-five, and she was childless, despite having been pregnant about eighteen times. A succession of miscarriages, stillbirths, and early child deaths had taken their heartbreaking toll.

At home, internal political machinations took up much of her time. Abroad, her armies were busy fighting the War of the Spanish Succession. Part of that conflict’s vast battleground included North America, where it was known as Queen Anne’s War.

Focusing the queen’s attention on the war named after her was the main purpose of bringing these powerful-looking men to London. These men represented England’s allies in the New World. England needed them in its conflict with New France and its Indigenous allies.

Their Christian names were Hendrick, Brant, John, and Nicholas. Their introductions to the queen were much longer and grander-sounding: Tee Yee Neen Ho Ga Row of the wolf clan, Emperor of the Six Nations and leader of the delegation (Hendrick); Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow of the bear clan, King of the Maquas (Brant); Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Row of the wolf clan, King of the Generethgarich (John); and etow Oh Koam of the tortoise clan, King of the River Nation (Nicholas).

Standing to the side was one of the men responsible for bringing then to England — Peter Schuyler, a colonial government official in Albany, New York. It was Schuyler who had talked the men — three Mohawks and a Mahican (Nicholas) — into making the trip. Schuyler believed that an appeal for more ships, troops, and arms to defeat the French in Quebec would arouse more sympathy if it came from these Indigenous leaders, who were known as sachems.

“Great queen,” began the speech from the sachems. “We have undertaken a long and tedious voyage, which none of our predecessors could be prevailed upon to undertake.” They went on to describe how “we have been as a strong wall for [the English settlers’] security even to the lives of our best men,” but that without help they would not be able resist the French and Huron forces.

Queen Anne may have sighed inwardly to hear this familiar request for more military help — yet another drain on the royal treasury. But she likely perked up when the sachems, through an interpreter, asked for Protestant missionaries to be sent to instruct them in Christianity. This would have been close to her heart, for the suffering monarch — who would be dead in four years — found great solace in religion.

She arranged to send missionaries, communion silver, and copies of the Bible. She plied the sachems with other gifts as well, such as kettles, looking glasses, a magic lantern, and four hundred pounds of gunpowder. And, happily for Schulyer and the beleaguered settlers back in New England, she committed ships and men for an invasion of Quebec.

The monarch made sure the sachems were well entertained during their stay. They took in theatrical performances, bear fights, wrestling matches, and sumptuous banquets. They toured London’s finest shops, floated down the Thames in the queen’s barge, visited the royal astronomer, and worshipped at St. John’s Cathedral.

Sometime during this whirlwind of activity, they managed to sit still, briefly, to have their official portraits painted.

Artist John Verelst had to work fast. In all likelihood he only had enough time to sketch their faces. The rest would be filled later.

“The problem Verelst faced, beyond the purely mechanical problem of putting the pieces together to make a satisfactory whole, was how to indicate the origin and status of these four royal visitors,” writes John G. Garratt in The Four Indian Kings (1985).

“Were they merely curiosities or were they serious envoys of a respected power? ... Generally, Indians were represented as exotic, befeathered creatures. The attempt to paint them as human individuals was virtually unprecedented.”

Indigenous people from North America had been seen and documented in Europe long before the four chiefs visited.

Verelst might have known about some obscure sketches made of an Inuit woman and child who ended up in the Netherlands in 1567 after having been kidnapped by French sailors in Labrador. The owners of an inn in The Hague had charged admission to see the mother and daughter dressed in their sealskins.

Verelst also would likely have been familiar with some renderings done by John White, a member of English explorer Martin Frobisher’s Arctic expeditions in 1576 and 1577. White created portraits of Kalicho, Arnaq, and Nutaaq — an Inuit man, woman, and child whom Frobisher captured and took to Britain. Unfortunately, all three died within a few weeks of arriving in England, probably of infections against which they had no immunity.

Another Indigenous portrait of which Verelst might have been aware was one of Pocahontas done by Dutch engraver Simon van de Passe. Pocahontas, the daughter of a Powhatan chief, is well known in American folklore for assisting the struggling settlers of Jamestown, Virginia. She married tobacco grower John Rolfe and in 1616 accompanied him on a visit to England, where she became an instant celebrity. Alas, Rebecca Rolfe, as she was known, succumbed to some European disease less than a year after landing in England. She was twenty-two.

Van de Passe’s portrait puts her in a ruffed collar and a Puritan-style hat — she looks nothing like the Pocahontas of today’s Disney fame.

Other Indigenous people who had been seen in Europe at that time included Tisquantum, a.k.a. Squanto, who famously helped the Puritans in Plymouth survive after their first terrible winter. Squanto was a Wampanoag from present-day Massachusetts who was twice kidnapped by the English and taken to Europe. He barely escaped slavery in Spain.

Explorer Jacques Cartier was not above kidnapping, either — he abducted an Iroquoian chief’s sons and sent them to France to be trained as interpreters.

The “Four Indian Kings” of 1710 could count themselves lucky: They were in England voluntarily; their visit was entertaining but brief — from April 1 to May 14 —and there are no reports that they contracted any of the serious infections, such as smallpox, that thrived in the filth and crowds of London.

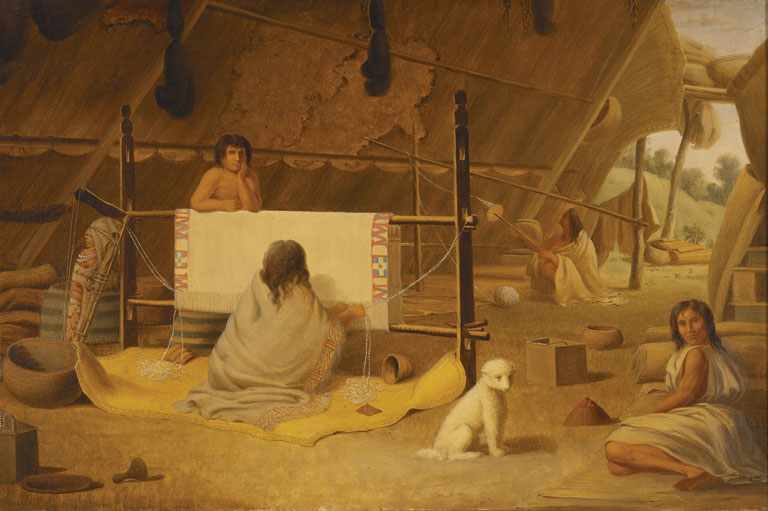

Verelst portrayed the sachems the way he would have painted any nobleman. He put them in an authoritative standing pose, wearing classical clothing and surrounded by the symbols of their occupation and status. The guns and bows of hunting and war craft are part of the picture; so are the animals representing their clans.

The result is strangely arresting.

Writes Garratt: “It is just because they do exist uneasily between the alien and the ordinary, between the New World and the Old, that they linger in the mind’s eye. From within the stiff conventional poses, something strange looks out, reminiscent of all that has gone on between Indians and Europeans, of all that has been lost and won.”

Nicholas, Hendrick, John, and Brant lingered in British society long after their ship, the HMS Dragon, had transported them home. Their speech to the queen was printed and reprinted, their portraits were engraved in mezzotint so that they could be reproduced, and a ballad concerning the youngest sachem’s supposed attachment to a woman he saw walking in St. James Park proved popular well into the nineteenth century.

Although the sachems’ own impressions are not reliably recorded, writers of the time did not hesitate to imagine what went through their minds. For instance, The Spectator, a periodical published in London, quoted Hendrick as finding the clothing of the English “very barbarous, for they almost strangle themselves about the neck, and bind their bodies with many ligatures.”

They were held up as ideal, “natural men.” One anonymous writer supposed that their wholesome way of life freed them from “those indispositions our Luxury brings upon us,” such as “gout, dropsy [edema], or gravel [kidney stones].”

They were not invulnerable, though. In fact, Brant died soon after returning to North America; what he died of is unknown. His name lives on today in the city of Brantford, Ontario. His grandson was the famous Mohawk leader Joseph Brant, a Loyalist who fled to Canada after the American Revolution.

Nicholas and John melted into obscurity after returning home. But Hendrick lived a long and influential life, eventually returning to England in 1740, where he had an audience with King George II.

Hendrick continued to play an important role in colonial affairs. Thomas More — a naturalist who had met Hendrick in London in 1710 — wrote of meeting him again at a conference in Boston ten years later: “He is now a Polite Gentleman Baptized, a Zealous Christian apparelled as we, speaks pretty good English and Scarsely distinguishable from an Englishman but by his tawny complexion....”

Hendrick would have been an old man when he died fighting the French at the battle of Lake George in 1755.

Fighting the French had, of course, been the original impetus for the sachems’ visit to London in 1710. Queen Anne did, as promised, send a fleet of warships to Boston in 1711. Sixty vessels under the command of Sir Hoven-den Walker sailed towards Quebec but lost their bearings in the St. Lawrence. Many of the ships ran aground on Ile-aux-Oeufs and at least eight transports were wrecked. Conceding defeat without even firing a shot, the rest of the fleet drifted home.

Verelst’s now-famous portraits of the Indigenous sachems had their own dangerous brush with destruction. Originally hung in Kensington Palace, they were at some point moved to Hampton Court, another royal palace in London. By 1851, they had left the royal household for a new home in the private collection of Lord Petre of Thorndon Hall, Essex. In 1878, a fire ravaged Thorndon Hall. Fortunately, the paintings escaped the worst of the damage and were cleaned and restored.

The paintings remained with the Petre family until 1977, when they were purchased by the Public Archives of Canada (now Library and Archives Canada). They have not been shown in Canada as a group since an exhibition in Halifax in 1989.

Senior LAC curator Eva Major-Marothy calls the “Indian Kings” paintings “among the most significant treasures held by Library and Archives Canada.”

Yet, most of the time they are in storage, along with about 20,000 other portraits. All of these were to have been part of the new national portrait gallery that was announced in 2001 by the Liberal government of Jean Chretien. Construction of the gallery has been stalled under Stephen Harper’s Conservative government.

The public showings scheduled for this year are a rare opportunity to glimpse the faces of the men who were regarded with great awe by Europeans three centuries ago ... and who continue to amaze us still.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!