Saved from the Wreckage

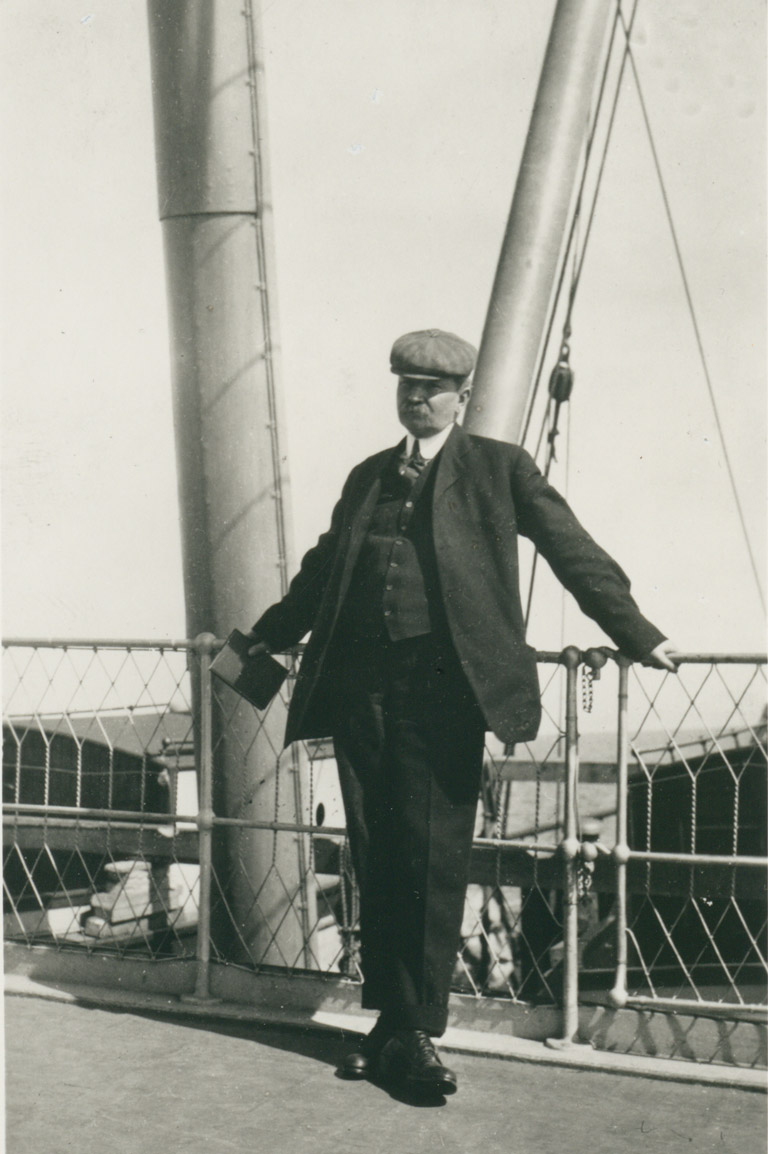

It was supposed to be just another collecting trip. In 1910, James Macoun, assistant naturalist with the Geological Survey of Canada, was sent to the northwest coast of Hudson Bay to secure specimens for the new Victoria Memorial Museum in Ottawa. Jim, or “Jimmy,” Macoun had been doing this kind of summer fieldwork for almost three decades. Initially trained as a botanist, Macoun was a formidable field collector, often working under difficult and hazardous conditions in remote areas and bringing back specimens from a wide assortment of plant and animal species. A Geological Survey paleontologist once remarked after a fossil-collecting expedition to western Canada, “Give me James every time. He knows no fatigue and fears no danger.” Macoun’s visit to the west coast of Hudson Bay, though, was no ordinary trip with no ordinary ending. The Victoria Daily Times claimed that Macoun’s adventures “read like a page of fiction,” while the Vancouver Province suggested that the story was “almost beyond belief.”

James Melville Macoun was the eldest son of professor John Macoun, a prolific field naturalist and a champion of the agricultural potential of the Canadian prairies. Known as the “father of Canadian botany,” the elder Macoun was appointed Dominion botanist to the Geological Survey of Canada in 1881 and founded the Dominion Herbarium, now the National Herbarium of Canada. Born in 1862 in Belleville, Canada West (later Ontario), Jim initially studied law before a career-changing detour as a field assistant for the Geological Survey in 1883. Thereafter, as a member of the temporary staff, Jim worked alongside his father, gathering flora and fauna specimens during the summer field season, while describing and cataloguing the items during the winter months.

The younger Macoun’s big break came in 1891 when he helped with the British-Canadian case at the Bering Fur Seal Arbitration Tribunal in Paris. The case involved a dispute between Canadian and American sealers over the right to harvest fur seals in the Bering Sea and on the American-owned Pribilof Islands, 450 kilometres off the west coast of Alaska. Canadian officials were delighted with Macoun’s findings regarding the nature and habits of the migratory seals, which supported Canadian sealers’ claims.

Over the next two decades, though, Macoun’s outspoken nature and political leanings hampered his career advancement. He once told a close friend that the government could hardly be expected to promote him, since — in contrast to his Conservative father — Jim was “a rabid socialist ... so far gone I contribute a column or two of stuff to a Labour paper here every week.” By 1910 he had been taken out of the field after writing a damning report about the agricultural potential of the Peace River Valley in northern Alberta, in which he opined that it was a “poor man’s country” for “people who, never having had much, will be satisfied with very little.” This assessment set off a firestorm of criticism from western expansionists, and Macoun was relegated to preparing natural-history displays for the soon-to-be-opened Victoria Memorial Museum.

Then, in 1910, his second lucky break came: A colleague had poisoned his fingers while using arsenic to prepare specimen skins, and Macoun was dispatched in his place to investigate the natural history of the Hudson Bay region. Excited at the prospect of getting away north, Macoun was determined to show how wrong the government had been in keeping him from the field. He sought advice from American biologists about what specific birds and mammals should be secured. “I want to work on the lines that are of the greatest scientific value,” he wrote.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The Hudson Bay coast was remote, sparsely populated, and difficult to access from southern Canada. That seemed likely to change, however, with Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier promising to build a railway to carry grain from the prairies to a terminus at Churchill in what was then Keewatin District, Northwest Territories, and is now northern Manitoba. The intention was to load the grain onto ships and send it to Europe. The anticipated coming of the Hudson Bay Railway nudged the Royal North West Mounted Police (RNWMP) into expanding its presence along the coast.

In 1910, the Mounties had only two detachments in their “M” Division, which spanned the west and northwest coast of Hudson Bay Keewatin District. One detachment was at Cape Fullerton, built in 1903 at the northwest top of the bay where American whalers overwintered; the other was further south at Churchill, built in 1905 at the site of a former Hudson’s Bay Company post. The police proposed to place prefabricated shelter huts, a precursor to posts, at three additional locations on the northwest coast of the bay in present-day Nunavut — Eskimo Point (now Arviat), Rankin Inlet, and Chesterfield Inlet — as well as a possible fourth hut still farther north at Wager Bay or Repulse Bay (now Naujaat). To carry out this work, the force had chartered the services of the Newfoundland-based wooden schooner Jeanie for the summer for $6,000.

Macoun travelled aboard the steamer Stanley from Halifax to Churchill, reaching the mounted police post as the Jeanie was preparing to set sail up the western coast of the bay. He immediately made arrangements with the Mounties and the schooner skipper to travel on board, believing it would enable him to collect specimens over a wide range of territory with relative ease. The Jeanie, however, did not inspire confidence. She was lucky to have made it as far as Churchill from her home port in Newfoundland and was already sporting a gaping hole in her patchwork sail. The crew was apparently little better. “I would not like to be stranded ... up north with a crew of such fellows,” Macoun later remarked. The schooner’s one saving feature was its auxiliary gas engine.

On August 25, 1910, after several days collecting around Churchill, Macoun sailed north along the western rim of Hudson Bay aboard the Jeanie. The schooner’s nine-member crew was captained by Harold Bartlett, who doubled as navigator. Harold came from a renowned Newfoundland sailing family whose members included Bob Bartlett, who famously captained Robert Peary’s vessel during his second attempt to reach the North Pole in 1905–06. But the Jeanie expedition was Harold Bartlett’s maiden voyage into the Hudson Bay region, and his inexperience would become a liability as he was tested by unstable weather. Other schooner passengers included RNWMP Superintendent Cortlandt Starnes (a future Royal Canadian Mounted Police commissioner), a sergeant, four constables, and a doctor. Three Inuit couples served as guides.

Macoun spent two days collecting at Eskimo Point and Rankin Inlet while the portable houses were erected. He was surprised to discover an intermingling of Arctic and more southern plants at these places — he had expected to find only Arctic flora. He also gathered information from Inuit inhabitants about the distribution and habits of local birds and mammals. This fieldwork was supplemented with photographs. While drying his plant specimens, Macoun used the time to wander about snapping pictures.

The next stop at Chesterfield Inlet had to be abandoned because of “dirty weather,” and the schooner made for Cape Fullerton, where she was nearly wrecked on the rocks during a rain squall. “All hands made ready for the worst,” Jim scribbled in his field notebook on September 3. “Had the vessel been wrecked in the dark there would have been little hope.”

Starnes and four other policemen remained behind at the Cape Fullerton RNWMP detachment, while Macoun, one constable, and the Inuit guides continued north to Wager Bay, where the last hut was to be placed. Their arrival there was delayed because of a sluggish ship compass that took them off course eastward towards Southampton Island. According to Macoun’s last diary entry on September 9, with the Jeanie anchored in a small cove in Wager Bay, a fierce snowstorm with gale-force winds came up in the afternoon, broke the anchor chains, and violently drove the ship aground that night. The schooner listed and slowly began to take on water. Fortunately, when daylight broke it was low tide, and everyone on board scrambled safely ashore.

Macoun had been shipwrecked almost twenty years earlier. In 1892, during his investigation of the Pribilof Islands seal rookeries for the Fur Seal Arbitration Tribunal, he had nearly drowned when his ship struck a rock off the Queen Charlotte Islands (now Haida Gwaii), British Columbia. He drew on that experience and, together with RNWMP Constable J.G. Jones, ordered everyone to take refuge in the new shelter hut while they assessed the situation.

The wreck of the Jeanie left them with two small boats: a gasoline launch and a whaling boat that had been used to ferry cargo ashore. Both boats had been smashed on the rocks during the storm. Over the next week, the stranded crew and passengers repaired the craft to make them seaworthy. The nearest settlement was the mounted police detachment at Cape Fullerton, nearly 250 kilometres south along the coast. They faced the prospect of waiting out the winter there — if they made it.

Because of space limitations, baggage and any extra clothing had to be left behind at Wager Bay. Macoun’s animal specimens suffered the same fate and were abandoned aboard the Jeanie. His collection of marine life was also sacrificed when the tank in which it was housed was confiscated to carry fresh water after the shipwreck.

Macoun refused, however, to part with his botanical collections. “It was only by intimidation,” he later told the Geological Survey director Reginald Walter Brock, “that I was allowed to take my specimens with me.” Macoun also wrote letters to his father and children in the event that he did not return home alive. It is not known what the letters said, nor what became of them.

Macoun and his party set off on September 16, with the gasoline launch towing the whaling boat. They took three days to reach Cape Fullerton, often losing sight of the coast along the way. American Captain George Comer had just put his whaling ship, the A.T. Gifford, in winter quarters at Cape Fullerton, but he agreed to take the party down to Churchill, more than six hundred kilometres distant. The Jeanie refugees arrived back in Churchill exactly a month after they had left it.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Because of the lateness of the season and the freeze-up of the bay, Macoun could not return home by ship. He consequently did some more collecting in the area — mostly gathering bird specimens — until the terrain had frozen and it was safe to travel on foot across the landscape riddled with lakes, rivers, and wetlands. His plan was to walk nearly one thousand kilometres south to Gimli, Manitoba. He would not be alone. A handful of men from the Canadian Hydrographic Survey, who had also been stranded at Churchill, joined him on the trek. So too did the Jeanie’s captain and crew, who had come to rely on his leadership.

Many of those travelling with Macoun, especially the Jeanie crew, had to learn to use snowshoes. The few dogsleds that had been secured at Churchill were reserved for supplies and gear — and for the ninety kilograms of natural-history specimens Macoun had accumulated. There were no tents. The mounted police supplied the men with winter outfits and sleeping bags lined with rabbit fur. Macoun borrowed fresh undergarments from a doctor in Churchill, since the only clothes he possessed were the ones he had worn at the time of the shipwreck.

The long walk south started on December 5, 1910, several weeks after the press in southern Canada had begun to speculate about Macoun’s fate. The men, travelling in two groups with Indigenous guides from Churchill, made first for Split Lake, a Cree community on the Nelson River in Keewatin District. Deep snow made for difficult walking. So did surface water on some of the frozen lakes. Every night the men’s feet were inspected for signs of frostbite or gangrene.

The next leg to Norway House — still in Keewatin District and just north of Lake Winnipeg on the Nelson River — was equally demanding. This time it was brutally low temperatures that caused the men to suffer. Macoun later told his father that he had “never dreamed of such cold before.” A few had their cheeks scarred from frostbite. The cold and snow remained constant companions until the men reached Gimli, at the bottom of Lake Winnipeg, six weeks after setting out from Churchill. Macoun was twenty-three pounds lighter. After he telegraphed his whereabouts to his relieved father and family, he made for Winnipeg, where he caught the first train to Ottawa. He reached home on January 18, 1911, along with his specimens for the new museum.

In his official report, Macoun talked about how he had completed the first known botanical survey of the west coast of Hudson Bay and how it would assist in mapping the range of Arctic and Subarctic species. More than three hundred botanical specimens he collected on that trip continue to reside in the National Herbarium that his father founded. Kept by the Canadian Museum of Nature, the successor to the Victoria Memorial Museum, the herbarium contains more than one million specimens, including the world’s largest and most comprehensive collection of Canadian Arctic plants.

“James Macoun’s 1910 specimens from northern Canada capture snapshots from a region and time characterized by challenges to travel and specimen preservation that are much greater than those our researchers face today — and even now, there are many gaps in the map of specimen collections in that part of the country,” said Jennifer Doubt, botany curator at the Canadian Museum of Nature. “That Macoun went there, and despite the hardships returned with excellent specimens, speaks to his focus and tenacity…. As environmental change from climate shifts and human activity accelerate, we’ll look increasingly to specimens collected in those remote areas — including those collected by James Macoun — to document the impacts and implications of that change for our ecosystems and futures.”

Despite his gruelling efforts to save his specimens and to bring them home, Macoun’s field expenses were questioned by the Auditor General’s office. He had to make a special appeal to cover the purchase of snowshoes, moccasins, and winter clothing in Churchill for the overland trip to Gimli. One wonders if the government would have paid for the undergarments he borrowed from the Churchill doctor.

In his newspaper interviews, Jim Macoun chose not to make a big fuss about his Hudson Bay adventure. “We had very little hardship,” he informed the Ottawa Citizen the day after his return. “The wreck and the predicament it left us in made very little difference, either to me personally or to the object of my trip.” Privately, it was a different story. Macoun confided to a colleague at the Geological Survey that the wreck of the Jeanie could have ended much differently if he and RNWMP Constable Jones had not assumed command of the situation. The crew was little better than useless after the ship ran aground and began to take on water.

He also made a telling admission to Captain Bartlett after he was safely home. Not only was the ship poorly equipped and supplied, but it was in no shape to make the trip along the western rim of the bay. “For my own part,” Macoun wrote, “I was very thankful that the ‘Jeanie’ was wrecked in Wager Inlet as ... I had very grave doubts as to whether we should get [out] safely.”

He added, “The less said about it the better.”

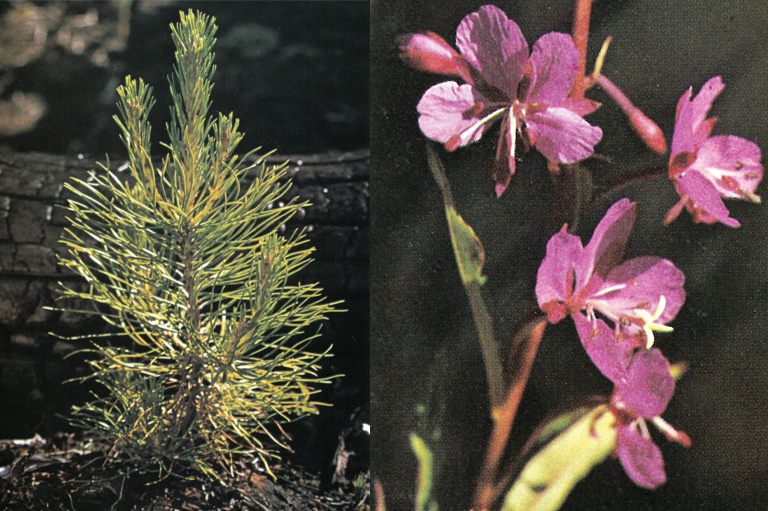

Botany in the Bay

The many plants Jim Macoun collected on his 1910 Hudson Bay expedition include these specimens of Oxytropis bellii, or Bell’s Arctic locoweed; Arctanthemum arcticum, or Arctic daisy; Pyrola grandiflora, or large-flowered wintergreen; and Cassiope tetragona, or Arctic white heather.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement