A Hair-raising Tale

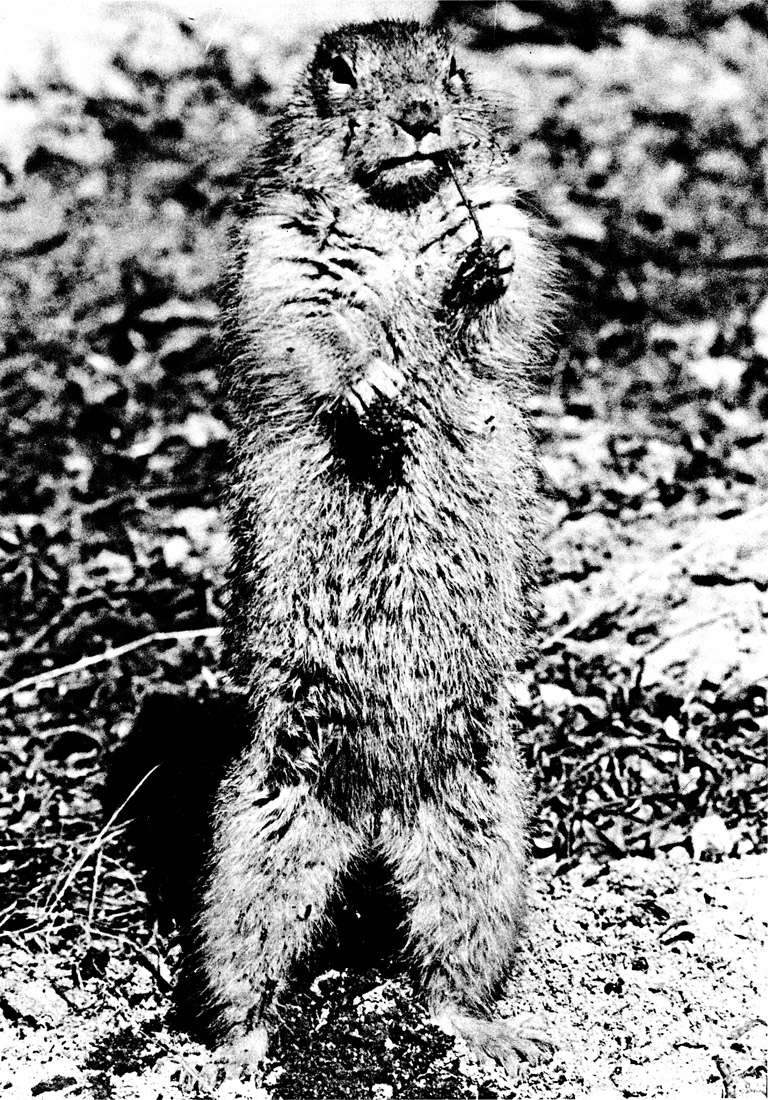

Imagine hunkering down in near sleep for more than half a year, only to emerge from your frozen den in a state of frantic hunger. And, as you desperately search through snow for bits to bite, you know that at any moment you might become someone else’s meal.

That, in a nutshell, is the frenetic and sometimes fraught life of the Arctic ground squirrel.

In the Spring 1972 issue of The Beaver, writer and photographer Fred Bruemmer shared his observations of the fuzzy wee mammals while he lived in Bathurst Inlet, in what is now Nunavut. His article, titled “Siksik,” began with the squirrels’ emergence from hibernation in spring.

“The pert little animals … emerged lean and hungry in early May, having lost more than half their weight during winter’s long sleep,” Bruemmer wrote. “Now the warmth of the spring sun had awakened them.”

Siksik, the Inuit word for ground squirrel, is also an onomatopoeic play on the sound ground squirrels make when chittering to each other. Bruemmer described how the newly awakened siksiks would tunnel through “deep snowdrifts to cope with the three main worries of siksik existence: to find food; to obtain territory and a mate; and to avoid being eaten by enemies.”

And there were plenty of enemies. Bruemmer described seeing the tracks of several predators near siksik dens, including those of wolves and foxes. High above, Arctic owls soared regularly over the tundra, searching for their next meals.

To thwart their enemies, the ground squirrels kept a wary guard as they scrounged for food.

“Every minute or so, a foraging squirrel sits bolt upright and looks carefully all around,” Bruemmer wrote. “The moment it sees danger, it begins to call its warning and the cry is picked up by all its neighbours, who rise high on their hind legs. The closer an enemy comes to a siksik, the louder it screams a rich, raucous string of malediction.”

For four short months during the spring and summer, the ground squirrels’ lives are a blur of finding food, wooing mates, and raising a new generation of young. By the fall, however, their thoughts turn to surviving the long winter to come.

“Summer in the Arctic is short and the ground squirrels know it,” Bruemmer wrote. “In four months, they must raise a new generation of siksiks, accumulate provisions for early winter, and above all, store up energy for the foodless winter months in the form of a thick fat layer. They are busy now, eating day and night, and carrying surplus food home in bulging cheek pouches.”

A Latvian-Canadian nature photographer, Bruemmer spent his career travelling extensively through the circumpolar regions. Born in 1929, he contributed regularly to The Beaver and was made a member of the Order of Canada in 1983.

He died in 2013.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!