Black Damp

In a hot summer morning in July 1932, in a small town in central New Brunswick, five young boys left home and went into the fields across the road to pick blueberries. By 11:00 a.m., they were ready for a break. Setting down their tin kettles half-filled with berries, they stopped at one of the abandoned mine shafts scattered throughout the area.

In a district where the coal seams ran close to the surface, this was a shallow pit, less than fifteen metres deep — more like a farmer’s well than an industrial colliery. A ladder-like wooden partition, built of planks with spaces between them, had enabled men to climb down to the bottom to work the coal, which was then hoisted to the surface. This pit — numbered as Shaft No. 10 — had not been in use for five or six years. The mouth of the mine was surrounded by boards built to a height of about one metre, but this fence was in disrepair and would do little to keep out a group of adventurous boys.

Three of the boys led the way. Curiosity and adventure are among the natural conditions of childhood, and it was not the first time they and other children had ventured down into the old mine. Easily getting through the fence, twelve-year-old Cyril Stack scrambled onto the rough ladder and began to climb down the shaft, followed by his ten-year-old brother, Vernon, and their nine-year-old playmate, Allan Gaudine.

The two youngest boys — Allan’s seven-year-old brother, Philip, and his six-year-old friend, Joseph O’Leary — hesitated at the top of the shaft before starting to follow the bigger boys down. They had not gone far when they saw the older boys fall and collapse at the bottom of the pit. Philip and Joseph climbed back up and ran for help.

This was the beginning of a short, suspenseful episode that is remembered in Minto, New Brunswick, as a time of tragedy and heroism. The day’s desperate events shed a harsh light on conditions in the local coal industry and had a large impact on public opinion. They ultimately led to changes in provincial law and to a workers’ compensation case that went all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

When the two boys came running home that morning of July 28, 1932, Joseph could be heard shouting: “They’ve fallen — they’ve fallen into the shaft!” and “Help, help, go to Taylor’s mine!” The first adult to rush to the scene was Bartholomew Stack, the eighteen-year-old brother of Cyril and Vernon Stack, both of whom lay unconscious at the bottom of the pit. At once, Bart, as he was known, went down the shaft — and collapsed at the bottom. Meanwhile, mine manager Alton D. Taylor had received word of the emergency from Joseph O’Leary’s mother. An assistant collected ropes, and Taylor picked up additional men on the running boards of his car as they drove to the scene. Among the men with Taylor were a young miner named Harry Tooke and the mine foreman, Harry Bauer, who was on his way home for dinner when he received word of the accident.

When they arrived at Shaft No. 10, the mothers of the three boys were already there. The sun was high overhead, and the boys could be seen at the bottom. Bauer and Tooke immediately started down the ladder, while other men prepared the ropes. Tooke fainted and fell on the way down, but Bauer reached the bottom and called out that one of the boys was alive.

By this time two more miners, Vernon Betts and Thomas Gallant, who worked at the nearby Shaft No. 12, had arrived. The two men started down into the mine together. Gallant fell from the ladder and collapsed, but Betts reached the bottom and helped Bauer to put a rope around Tooke, who was later hoisted to the surface. Betts started back up but lost consciousness on the ladder and fell.

Another miner, Ray Shirley, started to go down to assist Betts, but he was pulled back up when he began to lose his grip. By this time the mine foreman, Bauer, had also succumbed to the oxygen-deficient air. In addition to the three children, five men — Bart Stack, Harry Tooke, Harry Bauer, Vernon Betts, and Thomas Gallant — now lay incapacitated at the bottom of the shaft. Shortly afterwards they were joined by Dominic Gaudine, the father of one of the boys, who also fell unconscious while attempting to rescue his son.

Hundreds of men and women gathered at the surface of Shaft No. 10, and rescue efforts continued for several hours. In all, eleven men went down into the mine, attempting to rescue the children and then each other. As men and boys were brought to the surface, their muddied bodies were placed on the grass in a shaded area. Under the supervision of two local doctors, volunteers did their best to revive the victims. As a reporter for the Saint John Evening Times-Globe later wrote, “Men worked frantically over them, moving their arms this way and that in an effort to effect artificial respiration.”

The most determined rescuer among the coal miners was Mathias Wuhr, who tied a rope around his chest and held his breath while he was lowered down the shaft, which took about a minute and a half. He wore an improvised mask of gauze soaked in spirits of ammonia — supplies that Taylor, the mine manager, had rushed to obtain from the local drugstore. Wuhr descended five times and lost consciousness each time, but not before successfully putting a loop around each of four victims. Thanks to his efforts, the miners Stack, Betts, and Gaudine, as well as the young Allan Gaudine, were brought to the surface. The doctors refused to let him go down a sixth time.

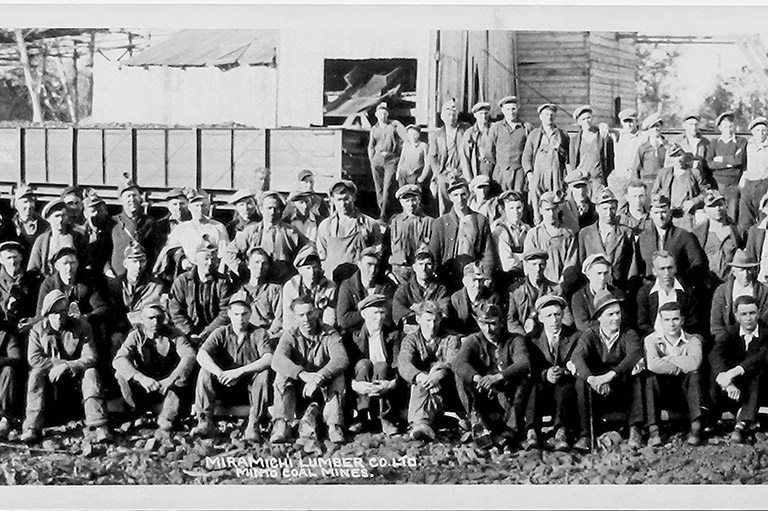

It is worth remarking on the spontaneous collaboration between Taylor and Wuhr. Taylor was a leading local citizen, a patrician figure with family roots going back to the Loyalists. He was the manager of mine operations for the Miramichi Lumber Company (owned by the New York-based International Paper Company) and was also the serving Conservative MLA for the area. Mathias Wuhr, on the other hand, belonged to an immigrant mining family from Germany and had come to Minto as a child by way of Cape Breton in 1914. Wuhr had been prominent only a few years earlier as a local leader of the militant One Big Union. But, in the emergency at hand, their differences in background and class were set aside.

When word of the accident reached the offices of the Department of Lands and Mines in Fredericton that morning, a supply of gas masks and a breathing apparatus were loaded into a vehicle to be driven to Minto, about an hour’s distance by road. The provincial inspector of mines, W.E. McMullen, arrived in time to provide a mask for the last of the rescuers, Norman Brittain, a young civil engineer doing land survey work in the area. The mask proved ineffective, and Brittain also passed out at the bottom of the shaft. In the end, nine rescuers survived a descent into the fatal pit, though several of them took weeks to recover from the ordeal. All of these efforts failed to save the three boys. Two of the rescuers, thirty-two-year-old Vernon Betts and forty-three-year-old Thomas Gallant also perished. It was obvious to the crowd gathered at the surface that the death toll could have been much higher that day.

Advertisement

The Minto mines were not known for dangerous or exploitative gases, and it later became clear that the bad air was the result of low levels of oxygen — what miners refer to as the “black damp” that can intermittently occur in mines for long stretches of time. The death certificates for all five victims named “Asphyxiation by Carbon Dioxide Gas” as the cause of death. Dr. G.I. Nugent noted that the boys had remained alive for thirty minutes to an hour after passing out. The implication was clear: They could have survived if they had been rescued without delay.

Several days after these events, a coroner’s jury investigated the deaths. Upon learning that there was no legal requirement to close up abandoned mines, the jury recommended that all disused mine shafts should be filled in. It also recommended that safety and rescue equipment should be provided throughout the district.

Unlike the neighbouring province of Nova Scotia, in 1932 New Brunswick had no explicit regulations to protect the safety of workers in the coal industry. Since the early 1920s, coal miners had been calling for laws to provide for the inspection and regulation of mine conditions.

They had joined the Nova Scotia-based district of the United Mine Workers of America, but the government had taken no action, and the mine operators had refused to recognize the union. When the miners then turned to the more radical One Big Union, there was a provincial inquiry into local grievances, but no reforms followed. A revised Mines Act in 1927 failed to provide for the inspection of equipment and conditions.

The deaths at Minto in 1932 — along with three other local mining fatalities that year — interrupted the history of public indifference towards safety in an expanding industry. In 1932, there were already more than six hundred men employed in the mines, producing more than two hundred thousand tonnes of coal for the province’s railways, mills, and factories. A thermal power plant had opened at Grand Lake, New Brunswick, in 1931, and the number of workers in the mines more than doubled over the course of the decade.

Inspector McMullen was well aware of the deficiencies in provincial law, and he reminded Premier Leonard P.D. Tilley that “the time has arrived when there should be some Provincial regulations making for greater safety in the operation of our mines.” After consultations with the coal companies, McMullen drafted a cautious set of amendments to the Mines Act, noting: “I tried to avoid anything which might be unnecessarily oppressive to the operators.”

Several provisions were borrowed from Quebec and Nova Scotia, including the requirement that underground workers be at least sixteen years old and that the working day could not exceed eight hours in any twenty-four-hour period. Surprisingly, the amendments included no requirements for first-aid equipment or rescue training. On one point, the new law was clear: “The openings to all abandoned mines, pits or slopes shall in all cases be filled in, securely closed or protected so that the same shall not be a source of danger.”

While the deaths of the three children and two rescuers attracted sympathy, there was no denying the effects on their surviving families. The brothers Cyril and Vernon Stack had lost their father in 1925 when he was killed in a mine accident. Their mother, who had remarried in 1930, was now left with one surviving son and two daughters; she was also pregnant with another child, who arrived two weeks after she lost her two boys. Allan Gaudine left two older sisters and a younger brother, Philip, who remembered being strongly affected by the death of the brother he called “my champion and guardian.” In his 2002 memoir, Philip Gaudine wrote: “I became terribly aware of the sorrow, sadness, and deprivation that prevailed in other homes throughout the town of Minto.”

Heavy burdens fell on the widows of the two rescuers. Greta Gallant was now responsible for seven daughters as well as twin boys. Grace Betts had five children to raise: three boys and two girls. “We were very young kids, every one of us,” Marguerite Betts, who was two years old at the time of her father’s death, recalled in an interview in 2005. “We all worked, we all had to do something. ... Mom was not a well woman; she was twenty-eight when Dad died, and by the time she was in her mid-thirties she had lost most of her eyesight, so we did not have it easy.” She also recalled the strenuous conditions facing the Gallant family: “Mrs. Gallant used to go out at night with pails and pick up the coal that had fallen off the boxcars along the track.”

In the weeks after the disaster, the widows expected to receive benefits under the Workmen’s Compensation Act, introduced in 1918 to assist the families of workers who were injured or killed on the job. Under the act, eligible widows could receive thirty dollars a month plus additional amounts for dependent children. But the Workmen’s Compensation Board turned down the widows’ claims in a two-to-one decision, on the grounds that the deaths of Vernon Betts and Thomas Gallant were “not the result of accident arising out of and during course of employment.” Chairman John Sinclair stated that the events did not meet the definition of “mine rescue” work, because they did not take place in an operating mine and they involved children rather than fellow workers.

This set off a long legal struggle. The case was appealed unsuccessfully to the Supreme Court of New Brunswick, but the Supreme Court of Canada then agreed to hear an appeal. When a decision was announced in December 1933, the court agreed unanimously that the Workmen’s Compensation Board’s reading of the law had been too narrow. The court also noted that the board had ignored the company’s responsibility for conditions in the shaft as well as the mine manager’s appeal for workers to join the rescue efforts.

As a result, on January 14, 1934, the Workmen’s Compensation Board rescinded its decision and allowed the widows’ claims. The following year, Grace Betts remarried, which, under the patriarchal assumptions of the time, disqualified her from continuing to receive a widow’s benefit; however, payments in support of the dependent children continued. Grace died in 1945 at forty-two years of age.

Save as much as 52% off the cover price! 6 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital.

Meanwhile, there was recognition for several of the rescuers. Nine men were nominated to the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission for awards celebrating self-less heroism. Under the fund’s strict criteria, only three names were approved, including Norman Brittain and Alexander Tooke, who received bronze medals and awards of five hundred dollars each. Mathias Wuhr received a silver medal and a cash award of one thousand dollars.

More than fifty years later, in 1983, the Minto Bi-Centennial Committee installed a commemorative plaque on a large rock at the entrance to the Minto Centennial Arena, not far from the site of the tragedy. Greta Gallant was on hand for the ceremonies and lived to reach 101 years of age. Since the original placement, the memorial has been moved to a location on Minto’s Main Street in front of the former train station, which is now a museum.

For many New Brunswickers, the 1932 disaster helped to give coal-mining families a human face. This was an important outcome, as the district featured a more diverse ethnic composition than was usually found in New Brunswick at the time. Besides workers from all parts of the Maritimes, including Acadians, the mines attracted immigrants with roots in the United Kingdom and in countries such as Belgium, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Russia, and Ukraine.

At the same time, the coal miners were giving up old habits of deference, and durable occupational solidarities were taking hold. Unionism resurfaced, and Local 7409 of the United Mine Workers of America was organized in 1937 with the working-class hero Mathias Wuhr as president. Before the end of the year the union was on strike, protesting “stone age conditions” in the mines and calling for better wages and more enforcement of mine-safety laws.

In retrospect, the 1932 disaster was a turning point in the coal miners’ quest for recognition in provincial society. Theirs was a story of resilience and survival, and they continued to make themselves heard throughout the following decades. Coal-mining operations were discontinued in New Brunswick in 2010 after the closing of the thermal power plant at Grand Lake, but the events of 1932 have not been forgotten.

The Most Dangerous Gases in Mining

Miners distinguish four types of hazardous “damps “— from the German word “Dampf, meaning vapour — that arise when toxic or explosive gases build up inside a mine. These gases may be the result of chemical processes like oxidation; they may be released during mining operations such as drilling and blasting; or they may be emitted in the exhaust of mining machinery such as diesel and gasoline motors.

CH4

Methane

FIREDAMP is mostly composed of methane, a highly explosive and flammable noxious gas. Pockets of methane occur naturally in coal seams and the gas can be released when the coal is mined.

CO

Carbon Monoxide

WHITE DAMP is predominantly made up of carbon monoxide, an extremely toxic, flammable and explosive gas produced by the oxidation of coal and during mine fires or explosions.

CO2

Carbon Dioxide

BLACK DAMP is a mixture of carbon dioxide and other unbreathable gases that displace oxygen, causing asphyxiation. Sources of carbon dioxide include rotting timbers, human and animal respiration, and coal itself.

H2S

Hydrogen Sulphide

STINKDAMP is the name given to hydrogen sulfide due to its smell of rotten eggs. Poisonous even in small concentrations, it is produced from the decomposition of iron pyrites.

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement