Canada’s Boy Miners

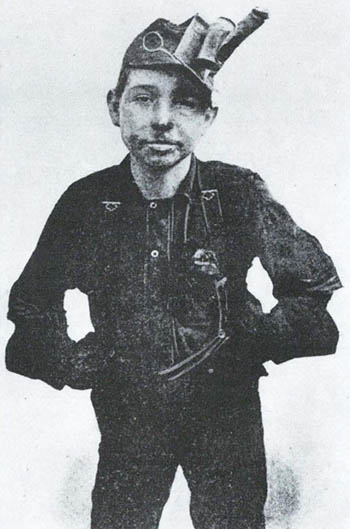

“Long before your city boys are astir the pit boy is awakened by the steam whistles, which blow three long blasts at half-past five o’clock every morning, thus warning him that it is time to get up. Breakfast partaken of, he dons his pit clothes, usually a pair of indifferent-fitting duck trousers, generously patched, an old coat, and with a lighted tin lamp on the front of his cap, his tea and dinner cans securely fastened on his back, he is ready for work. He must be at his post at 7 o’clock. Off he goes, and in a few minutes with a number of others, he is engaged in animated conversation, and having a high old time generally, as he is lowered on a riding rake to the bottom of the slope.”

— Halifax Morning Chronicle, 4 December 1890

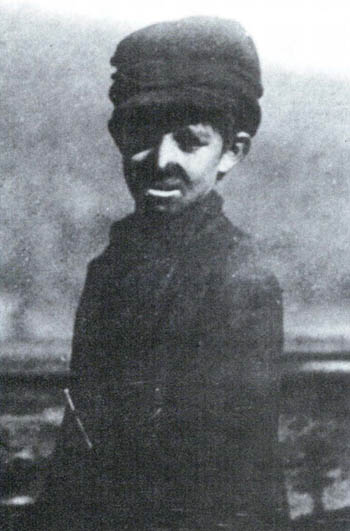

Like children in other late nineteenth and early twentieth century Canadian communities, boys in colliery towns and villages worked. Like other children also, these boys started to work at an early age. Even well after the turn of this century, according to mining historian Lynne Bowen, “if a boy who had lived in a coal town got tired of school and was anxious to make a little money, the obvious thing for him to do was to go to work in the mines. If he was willing to lie a little and add a couple of years to his age, he could start to work at 13 or 14.” A generation or two earlier, in the coalfields of Nova Scotia and British Columbia, boys as young as 8 laboured in Canadian mines.

Boys performed a variety of tasks at the Victorian colliery and constituted an important part of its labour force. In Nova Scotia, for instance, of a total mine workforce of five thousand in 1890, over eleven hundred were under 18 years of age. On the mine’s surface boys were employed to clean miners’ lamps, distribute picks, or run errands. They filled powder cans and tended mine animals—generally horses in Nova Scotia and mules in British Columbia. They sorted and cleaned the freshly mined coal.

The labour of boys was also useful underground. Although they were not actual miners—they did not cut coal—boys were indispensable to the transportation of the coal to the mine’s surface and to the ventilation of the mine. The oldest boys were employed to load the newly cut coal in to the tubs used to transport it out of the mine; others worked as brakemen and landing-tenders, removing the filled tubs as they came down from the miners’ workplaces and sending empty tubs back up.

Horses or mules, usually “driven” by boys aged between 13 and 16, were used to pull the tubs of coal to the slope. There, cage-runners were employed in attaching the tubs to the mechanical hoist or “rake” used in hauling them to the surface. The youngest mine employees, some as young as 8, were responsible for the vital yet excruciatingly tedious job of opening and closing ventilation doors called “traps”. “Trappers” sat all day in darkness, opening their trap to allow the drivers and their cargo to pass them, closing it to channel air up into the workplaces.

Few legal impediments to the employment of boys in the mine existed until well into the nineteenth century. (Girls, or for that matter any female, were never employed at Canadian collieries.) In Nova Scotia, the only significant provincial restriction on boy labour in the mines was a minimum age of 10 established in 1873 and raised to 12 in 1891.

Although in British Columbia regulations were nominally stricter (a minimum age of 12 was set in 1877; until the age of 14 boys were limited to thirty hours’ work per week), in the absence of more than a handful of mine inspectors in either province, these laws were not always observed.

From the point of view of the mine operator, then, boys could be employed to perform a variety of essential tasks within the mine at a significantly lower rate of pay than adult mine workers. In 1880, Nova Scotian boys averaged 65 cents per day worked; adult labourers earned 95 cents; adult miners, $1.45. Ten years later, at Nanaimo, a boy received $1 per day; adult mine workers received anywhere between $2 and $4 for a day’s work. Chinese workers in British Columbia were the exception. They were paid little more—and often less—than the boys, while performing similar work. As a consequence, much mine work that boys undertook in Nova Scotia was done in British Columbia by adult Chinese.

From his parents’ perspective, the boy’s labour provided extra revenue for the family purse. The money the boy earned was generally handed over to his parents as long as he lived at home—he received in return a small allowance. Although this may appear exploitative, the advantages of alternatives such as schooling were not apparent. Indeed, the view persisted that formal education in some way “spoiled” a boy destined by birth to labour in a manual occupation.

Boys responded to mine work in a number of ways. Certainly there were always individuals, generally older boys, who entered the mine workforce eagerly. They could gain experience in their probable occupation as adults while at the same time earning money. “They couldn’t keep me out of the mines,” recalled a retired Nanaimo miner, “I was bred a coal miner.”

Other boys were more reluctant to enter the mines. Most found themselves at work after their father had approached the mine manager to request a job. A retired New Waterford (Cape Breton) miner recalled as a boy “Coming home in the evenings and falling asleep while eating supper—the effects of rotten ventilation and damp. We in common with all boys, then obliged to work and eke out the family income, faced the prospect of a dismal and unhappy existence.”

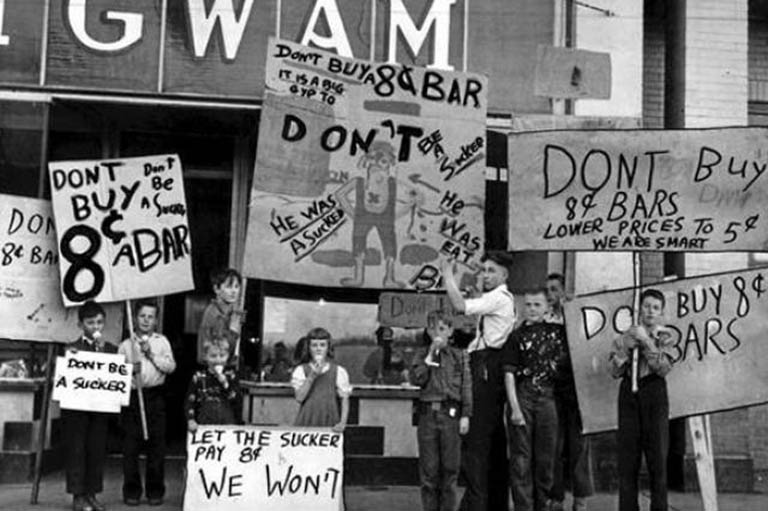

It was generally agreed, though, that in the mines the boys matured rapidly. Their behaviour towards both mine officials and older mine workers was highly assertive, reflecting a large measure of independence. Boys were described as “apt to take offence even more quickly than men.” They were commonly thought also to strike more frequently and more readily than adult mine workers.

Although the typical boys’ strike lasted only a day or two, their behaviour could have serious repercussions for other mine workers. When they struck the Springhill pits in 1906 for ten days, a public outcry developed against “foolish boys” who cost older mine workers, often their fathers, an estimated $17,170 in forfeited income.

In Bridgeport, Cape Breton, parents were not as patient. Parental authority was exercised after (horse) drivers had been on strike for four days in 1887. As the parents of the fractious youths considered that the step was ill-chosen they took the culprits in hand and sent them to work, reported the Trades Journal on 20 July 1887.

Typically, boys went on strike in defiance of mine officials’ attempts to exercise their authority. One official ordered a boy to travel through a portion of the mine the latter believed dangerous. “The boy refused,” reported the Trades Journal. “Harsh words passed between them, the boy using the harshest it is said.” When the official sent the boy home, the other boys walked out, closing that portion of the mine. Later, the official complained, the boy puffed smoke in his face on his way to church.

A boy’s career in the mine could take one of three courses. For the ambitious and the fortunate, positions in mine management were available. It was not uncommon for colliery officials to have been miners, particularly after the establishment of night schools of mining and the introduction of compulsory licensing, based on competitive examinations, of mine officials.

The career of J.R. Dinn in the “Caledonia” mine of the Dominion Coal Company provides an example. He first entered this mine at the age of sixteen, when he was employed to load coal into tubs. Good fortune, persistence, and night classes led to Dinn’s appointment as mine manager in 1921.

For the least fortunate, mine work could lead to death or disability. The mine was a dangerous workplace. Day-to-day accidents, seldom noticed outside of the mining communities, took their toll. The youngest mine workers, relatively inexperienced and inattentive, were subject to a higher rate of accidents. A boy died, for example, in 1882 at Little Glace Bay after being crushed by a roof fall. A kick from a horse split a driver’s nose in 1883; later that year a boy was run over and killed by tubs of coal at Sydney Mines.

The great disasters, much better publicized, killed fewer mine workers over the years. Most striking among these was the Springhill explosion of 1891. One hundred and twenty-five mine workers were killed immediately by the explosion, or were suffocated shortly afterward by toxic gases released by the blast. Seventeen of the dead were 16 years of age or younger.

Most boys would of course survive to be given a place as a miner when they grew to full strength, generally by the age of 18 or 19. In the meanwhile, boys would undergo an “apprenticeship” peculiar to the coal mines. Murdock McLeod, a Springhill miner with twenty years’ experience underground, testified before royal commissioners in 1889 that he had begun mine work at the age of 9 as a trapper; he had “worked “himself up” subsequently, spending years as a driver before getting a place as a miner.

Another Springhill miner, Elisha Paul, explained before the same commissioners the variety of boys’ occupations. Paul had been employed successively as a trapper, driver, brake-man, cage-runner, and loader before beginning to cut coal. When age or disability prevented the miner from continuing to work as a cutter, he could expect to be given light work on the surface, similar to that of boys. Some contemporary American mine workers said, “twice a boy and once a man is the poor miner’s life.”

The boy shared not only the workplace but also a community with older miners. The popular view of the turn of the century mining community, one which portrayed the miner as dissolute and thriftless, illiterate and degraded, failed to acknowledge the widespread commitment within mining towns and villages to Victorian ideals such as temperance, self-improvement and respectability.

Certainly some miners—and mine boys—played their part in perpetuating an unfavourable view of the miner. The revelry of payday was habitual. In Stellarton in 1888 two particularly “drunk and disorderly” boys aged between 12 and 14 were jailed in the course of their merry-making.

Nineteenth century elections were also boisterous occasions. “A hard looking sight was seen on [provincial] election day. Several small boys not more than 10 to 12 years, were seen paralyzed through drink,” reported the Trades Journal in 1889. Hallowe’en demanded its rituals also. The Trades Journal commended boys on their behaviour on that evening in 1887. “They contented themselves with waving torches and doing a little shouting.”

Some mine workers did spend all their leisure time in the “rum-hole”, a routine enlivened only by the occasional dog fight or cockfight or, more regularly, by a brawl among the miners. The smallest mining communities, where single men predominated, were the most notorious. Joggins, a mining village in the vicinity of Springhill, was reported to boast “one general store and, by report, twenty grog shops”.

Although Salvation Army officials had harsh words for all Nova Scotian mining towns on their arrival in that province in the 1880s, they were particularly demanding judges of human behaviour. Westville was labelled “the worst place this side of Hades”, and Springhill, “one of the dark spots of our Dominion, drinks, gambling and profligacy abounding.”

Like older mine workers, some colliery boys enjoyed their “wee drop” and provoked the ire of their more “respectable” contemporaries. These included not only Salvation Army officials but also fellow coal miners. “What would the village, or in fact any place,” complained the miners’ union newspaper, “be without the ‘wee drop’ that gives us more than school or college, that wakens wit, and kindles lore, and bangs us full of knowledge.”

Beside institutions such as the “rum-hole,” flourished others more in keeping with Victorian standards of conduct. Churches in Nova Scotia were at times supported by deductions directly from miners’ paycheques; a strong tradition of temperance existed as well in the province. Mine boys and their fathers participated in organizations such as the “Sons of Temperance.”

The principal activity associated with children today—their schooling—was undertaken before boys entered the mine workforce, or on days when the mine was not operated. Compulsory school attendance was introduced in Nova Scotia in 1883, but only for children aged between 7 and 12 and only for eighty days per year. In Cape Breton, where mines were closed for two or three months every winter, pit boys had an opportunity then to meet their schooling requirements.

Elsewhere this legislation might well be ignored. British Columbia had introduced province-wide compulsory attendance even earlier, in 1876, also for 7 to 12-year-olds. There at least six months’ attendance per year were stipulated. As was the case with mines legislation, though, in the absence of effective means of enforcement, school laws were not always observed.

The colliery boy survived well into this century. In British Columbia even a minimum age of 15 for mine work was not legislated until 1911; not before 1923 was Nova Scotian legislation forthcoming whereby boys under 16 were prohibited from mine work. Prior to those dates, however, their relative numbers in the mine workforce had dwindled as underground haulage and ventilation systems were improved and as adult wages rose.

Both factors reduced the need for child labour in the mines, as tasks they had traditionally performed became mechanized and as family need for their wages diminished. At the same time, provincial governments became more effective at enforcing the laws they passed. Means of inspection were improved and penalties were stiffened.

The child, excluded from the colliery, entered the classroom, a movement encouraged by increasingly stringent provincial regulations concerning compulsory schooling. By the end of the 1920s, the colliery boy had given way entirely to the school child.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement