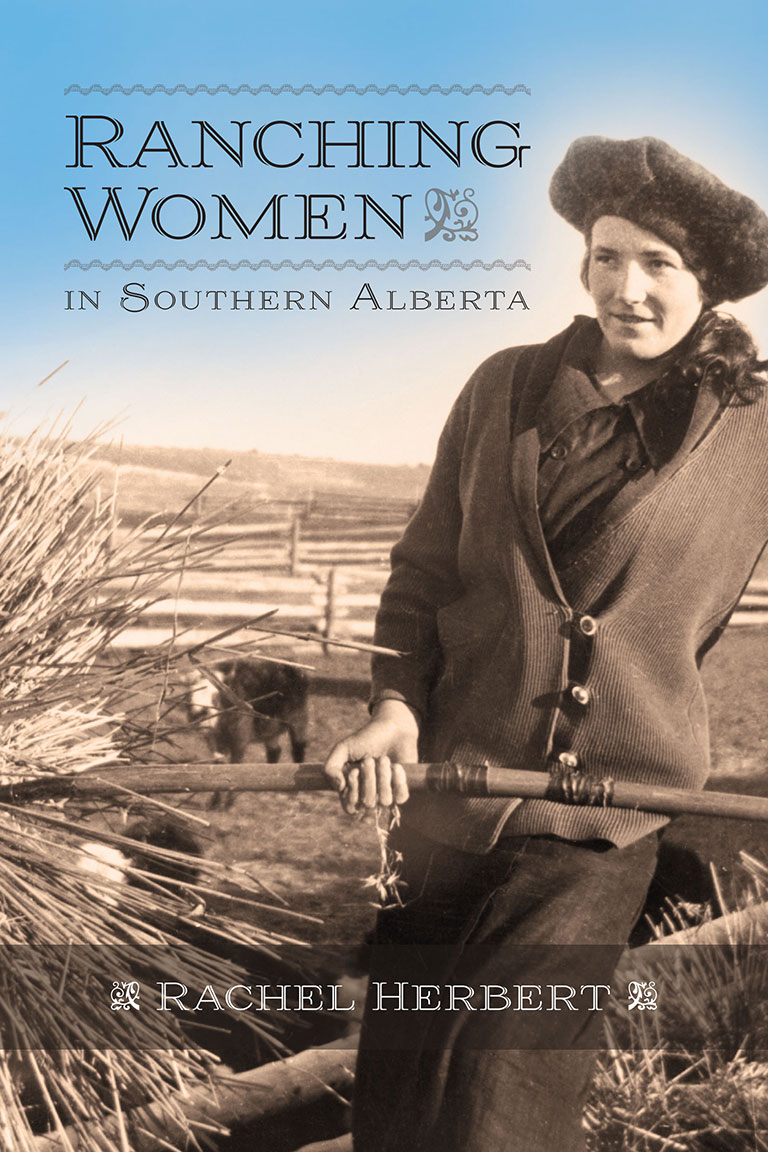

Ranching Women in Southern Alberta

Ranching Women in Southern Alberta

by Rachel Herbert

University of Calgary Press

212 pages, $29.95

A double review with

Ranching Under the Arch: Stories from the Southern Alberta Rangelands

by D. Larraine Andrews

Heritage House

320 pages, $29.95

Following two brutal winters, the romance of open-range ranching in southern Alberta died a quick and painful death. What seemed like a golden opportunity for ranchers in the 1880s — ample water, abundant native grass, generous grazing leases, and the chinook with its arch cloud formation and its warm winds — soured when the chinook winds failed to arrive in the winters of 1886–87 and 1906–7.

The bitter cold and deep snow proved disastrous for cattle. It’s estimated that the various herds roaming southern Alberta lost upwards of eighty and ninety per cent of their numbers over those respective winters. By 1912, open-range ranching was dead — as were many ranches, including some of the large corporate outfits.

The ranches that survived, however, were often small, family-run affairs that had adapted to the realities of ranching in southern Alberta by adopting farming practices, such as the use of fences and growing winter feed for cattle, and by embracing principles of conservation and stewardship.

Drawing from letters, diaries, books, and interviews, D. Larraine Andrews explores the history of ranching in southern Alberta in Ranching under the Arch: Stories from the Southern Alberta Rangelands. She tells the stories of seven founding ranches that are still operating today, including the McIntyre Ranch, the Midway Ranch, and the Waldron Grazing Co-operative.

Along with the history of these ranches, Andrews also explores how ranching in southern Alberta began, how it differs from ranching in other regions, and how it influenced Alberta’s history, economy, culture, identity, and environment.

Ranching started in Texas after the Spanish introduced cattle to North America in the 1500s, moving northwest and changing as it went, until, once in Canada, it grew into something distinctive.

“In reality it represented a uniquely hybrid combination of Old and New World culture, skill and expertise, heavily influenced by American, British and Eastern Canadian know-how and adapted to a frontier environment that demanded adaptation for survival,” writes Andrews.

In a remarkable story — of a group of people and a landscape — that helps to explain southern Alberta’s uniqueness, Andrews makes it clear that the land and the people cannot be separated.

“They made the rangelands their home,” she writes, “conserving and preserving the land for generations to come. In the process, they were instrumental in establishing the vibrant and successful ranching industry that remains a fundamental part of our history and our future as a province.”

The influence ranchers had on southern Alberta can be seen in many examples, such as the Calgary Stampede, established in 1912 to honour the end of open-range ranching, and the preservation of vast swaths of Alberta’s native rough fescue grasslands. Today, the 160,000-acre (65,000-hectare) McIntyre Ranch — founded in southeastern Alberta in 1894 — is home to the largest tract of fescue grassland in North America.

While the story of ranching in southern Alberta is very much about people in a place, it would be wrong to assume that all the people in this beautifully illustrated story are male.

Women — some of whom arrived from the city with little idea of what lay before them, and others, born into multi-generational ranching families, who learned at a young age how to ride and to rope — had a profound effect on ranching in southern Alberta and refused to allow the conventions of the time to dictate the work they did.

Theirs are remarkable stories in what is already a remarkable story. While Andrews provides rich insights into the lives of ranching women, she can only go so far, given the scope of her book. But that is where Rachel Herbert comes in with her book Ranching Women in Southern Alberta.

The two books share the same geographical and historical landscape, but Herbert — one of Andrews’ subjects and sources — offers a detailed history and analysis of the role women played on Alberta ranches. It was a role that, Herbert discovered, had not been well documented.

“Ranching women were largely invisible,” she writes.

“The early women who helped to settle the province had homesteaded and farmed, I read; they fed threshing crews, grew gardens, and raised large families. But what of my great-aunt Mary, who taught me to work a cow from horseback when I was eleven and she was eighty?”

In making this history visible, Herbert presents a carefully researched and thoughtful history of ranching women that is informed by her own experience. The women she features, including members of her own family, could do it all — and, in the process, they erased the line between men’s and women’s work.

Together, Ranching Under the Arch and Ranching Women in Southern Alberta share one of Alberta’s foundational stories while highlighting the roles of women and their influence on the province’s ranching history

Our online store carries a variety of popular gifts for the history lover or Canadiana enthusiast in your life, including silk ties, dress socks, warm mitts and more!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement