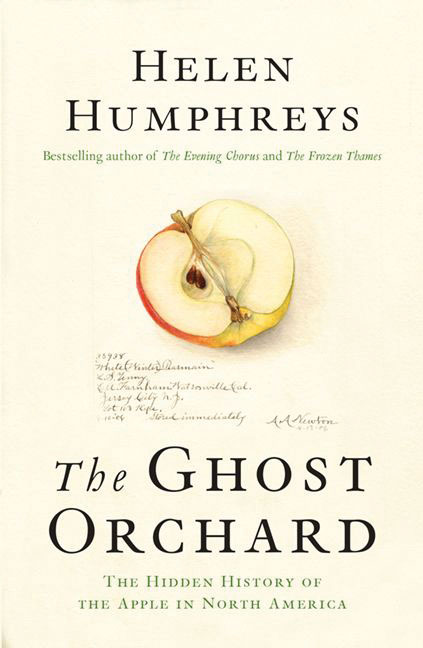

The Ghost Orchard

The Ghost Orchard: The Hidden History of the Apple in North America

by Helen Humphreys

HarperCollins, 268 pages, $29.99

“The past is all around us if we look carefully and can figure out a way to read it,” writes award-winning novelist and non-fiction writer Helen Humphreys. In The Ghost Orchard: The Hidden History of the Apple in North America she is inspired by the taste of wild apples found outside a log cabin near her home in Kingston, Ontario, to seek their largely unknown origins in terms of Indigenous peoples, women, and artists. This takes her beyond the recorded history of the apple, which, she says, “is the history of white settlement during the nineteenth century.”

In addition to gorgeous historical coloured plates created by seed-catalogue illustrators and botanical artists, the book brims with interest and captivating prose. An entire chapter is dedicated to poet Robert Frost, who planted an orchard at the age of eighty-three, perhaps in memory of his “glorious friendship” and “talks-walking” with the British poet Edward Thomas.

Another chapter opens with a description of every apple variety in the recreated orchard at John A. Macdonald’s Bellevue House in Kingston. A “Glossary of Lost Apples” at the end of the book highlights varieties of First Nations or Canadian origin.

A chapter entitled “The Indian Orchard” explores Indigenous and settler involvements in the spread of the fruit, including distinct varieties produced by Indigenous peoples. Meanwhile, “Ann Jessop” tells of the Quaker preacher known as “Apple Annie” for her distribution of diverse scions she’d carried back from Britain in the late 1700s, including the crisp, juicy White Winter Pearmain that starts Humphreys’ quest.

The beauty, fragrance, and fruit of apple trees lend poignancy to our relationship with them, as does the similarity of their lifespan to that of a person — around one hundred years at best, notes Humphreys. Her book was written as a close friend, a poet, neared death, and Humphreys’ father died soon after.

It’s a sociological and an agricultural account, detailing the reduction of over seventeen thousand varieties at their nineteenth-century peak to fewer than one hundred commercial varieties today; it’s also a moving meditation on memory and loss, friendship and family, the bequest of art and writing, and what remains in absence — sometimes with only a single tree to point us back.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement