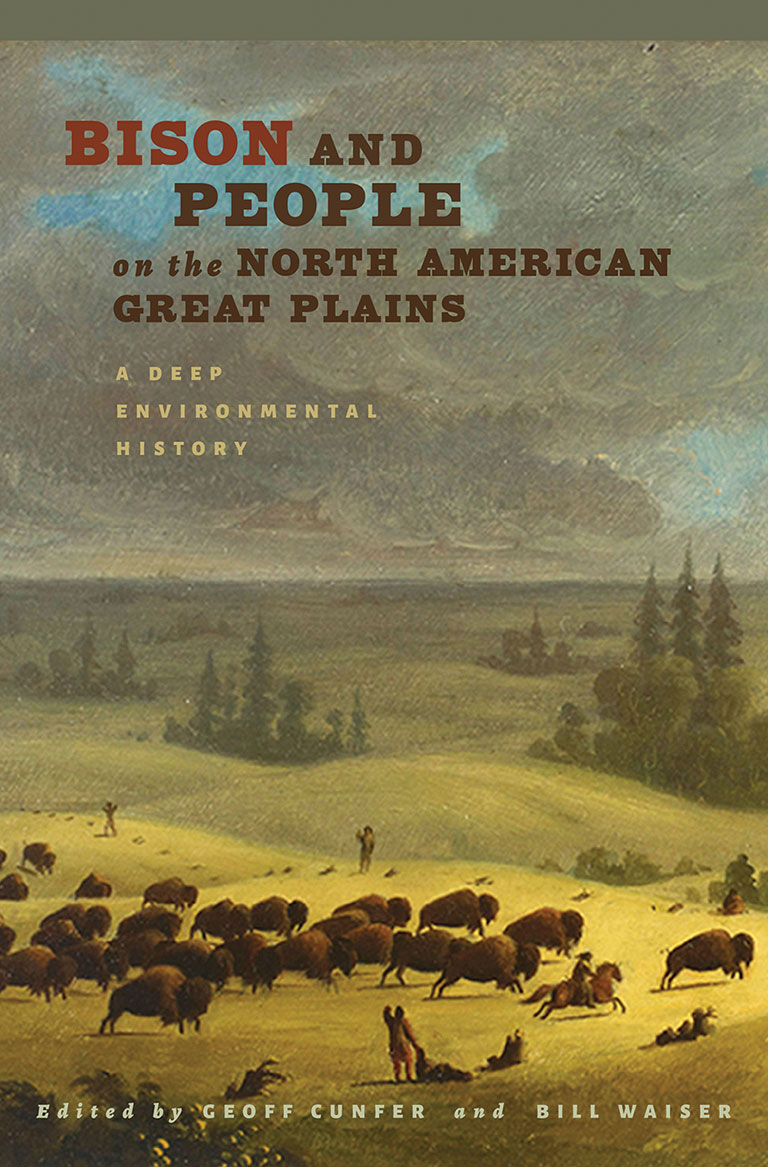

Bison and People on the North American Plains

Bison and People on the North American Great Plains: A Deep Environmental History

edited by Geoff Cinfer and Bill Waiser

Texas A&M University Press

339 pages, $82

I am likely not alone in having believed that bison all but disappeared from the West because of ruthless mass killing by white hunters. My schooling impressed me with stories of “sportsmen” picking off the animals from moving trains and letting them rot where they fell.

These things did happen. But, according to recent scholarship, the deliberate extermination of bison, which was carried out mostly across the border, was not the sole factor that led to their near extinction. What actually happened is more nuanced.

Bison and People on the North American Great Plains upends many commonly held ideas, such as that bison had always populated the plains in large and steady numbers. The prairie was once home to a diversity of large animal species. It was only after the extinction of most of them around nine thousand years ago — due to over-hunting, climate change, and other factors — that bison multiplied like weeds to cover the prairie. Nor was the prairie always prairie. Fires deliberately set by Indigenous people to clear forests and facilitate hunting had, by the year 1700, created a vast grassland in the centre of the continent. At this time, bison populations peaked to about twenty-nine million.

Then came the horses. Introduced by the Spanish in the seventeenth century, they were everywhere by 1750. They competed with bison for grazing land and provided hunters an efficient means of killing their prey. Dried bison meat — pemmican — was traded to other Indigenous tribes and later to European newcomers, which led to more bison being killed than were being reproduced, especially in the southern plains.

The bison herd had already been reduced by twenty-five per cent by 1840, when the story familiar to most of us began — the final slaughter fuelled by the demand for hides and the desire to clear the plains for white settlement.

This highly accessible book includes essays by academics from a variety of disciplines. While it includes the views of Métis and Lakota people, none of the scholars are described as Indigenous. However, it’s well worth reading for anyone interested in this fascinating period of environmental history.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement