Home Sweet Suburb

In September 1952 the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation opened Canada’s first two television stations in Toronto and Montreal, and over the next two years extended its television coverage into seven other major metropolitan areas. Television was hardly a new technology.

The British and Americans both had experimental television stations operating before the war, and the Americans had begun introducing comprehensive television broadcasting, with national network organization, in 1946. By 1952 I Love Lucy, American television’s first nationally popular hit show, had been running for over a year.

At the time of the introduction of television broadcasting in Canada only 146,000 Canadians owned television receivers (or “sets” as they were usually called), tuning to American border stations and using increasingly elaborate antenna systems to draw in distant signals. Most Canadians thus missed entirely the first generation of American television programming, broadcast almost exclusively live from the studio, and were able to tune in only as U.S. television moved from live to filmed programs and from New York to Hollywood.

But if Canada got a slightly late start into life with the tube, it rapidly caught up. By December 1954 there were nine stations and 1,200,000 sets; by June 1955 there were twenty-six stations and 1,400,000 sets; and by December 1957 there were forty-four stations and nearly three million sets. The rate of set proliferation had been almost twice that of the United States, and the market for new ones was virtually saturated within five years.

Perhaps more than the automobile, or even the detached bungalow on its carefully manicured plot of green grass, television symbolized the aspirations and lifestyle of the new suburban generation of Canadians. Unlike other leisure-time activities that required leaving the home, it was a completely domesticated entertainment package that drew Canadian families into the home.

Until the late 1960s most Canadian television sets were located in the living room. Particularly on weekend evenings in the winter, the only sign of life on entire blocks of residential neighbourhoods was the flickering dull glow of black-and-white television sets coming from otherwise darkened houses.

The family could even entertain friends who were interested in the same popular programs. Some of what people watched was Canadian-produced, but most of it came from the Hollywood Dream Factory. Despite the Saturday-evening popularity of Hockey Night in Canada, which was first telecast in 1952, television drew Canadians into the seductive world of American popular culture.

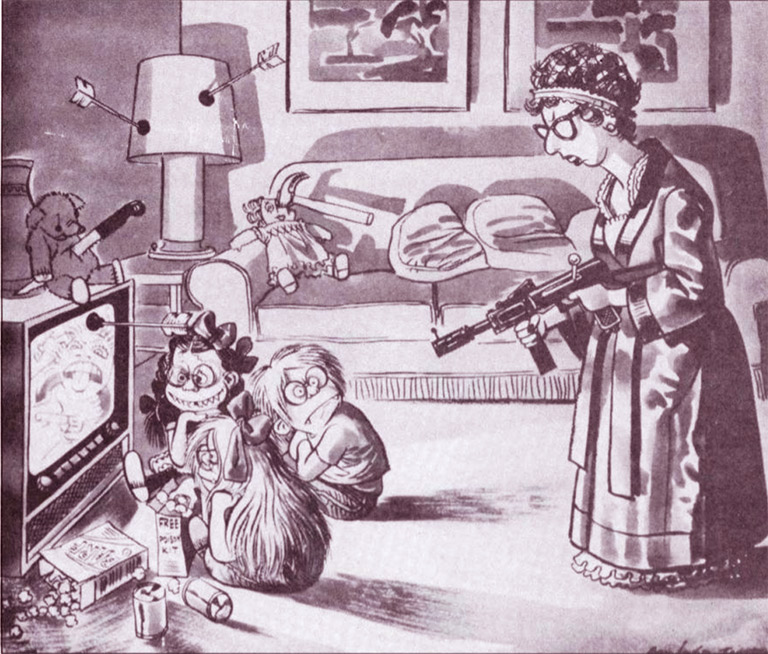

Everyone watched television, but perhaps none were more influenced by it than the young, whose perceptions and reading abilities were greatly affected by their being transfixed by an endless array of images.

After the war the serious housing shortage — there had been little new domestic building since the 1920s — and a spate of young couples starting their lives together led the government, through the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), to promote suburban development, offering very cheap mortgages. The suburbs were built quickly by companies that had gained expertise during the war, and were often developed around a school. The municipalities then had to link these new communities to each other, and to the city, through roads and infrastructures.

Suburbia was a physical place of detached and semi-detached houses with yards and lawns around the outskirts of a city, but it was also a rather complex constellation of expectations and values centred on the home, the family, and continued economic affluence.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

In overall terms the trends for urban and rural residency established in the early years of the century continued through the period 1946 to 1972. Urban population steadily increased, both absolutely and as a proportion of the total, while the numbers of rural inhabitants remained relatively constant.

Within the rural population, however, there occurred a massive decrease in the number of farm residents, from 3,117,000 in 1941 to 1,420,000 in 1971. Declining numbers of farmers was a national trend, most evident in these years in provinces still dominated by agriculture: Prince Edward Island, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan.

On PEI for example, the number of farms declined from 12,230 in 1941 to 4,543 in 1971. Farm depopulation was caused by no single factor. The continued inability of the farmer to make a decent financial return on labour and investment was undoubtedly one of the prime factors. Canadian farms got bigger and more mechanized in an attempt to compensate for low rates of return per acre, and many farm families gave up and got out when the older generation still left on the farm died.

Farm land anywhere near cities became uneconomic to retain for farming, and most of Canada’s finest agricultural land — in the Fraser Valley in British Columbia and in southwestern Ontario — had been sold to speculators by 1971 or cut into hobby farm plots. Many former farm families discovered they did not have to move to enjoy brighter lights, for the outskirts of cities expanded in all directions into rural areas.

While Canadian cities grew significantly in size, little of that population growth occurred in the downtown areas or the traditional residential sections. The trend in the downtown core was just the reverse. Rising land prices made it uneconomic for land there to be used residentially, except for high-rise apartment blocks, which were less profitable uses of space than comparable office blocks and thus emerged only on the fringes of the downtown. Building upwards, the core of the business district produced those breathtaking skylines we have come to associate with the modern city.

Gradually, beginning in the 1960s, they came to be dominated by buildings that showed vast expanses of tinted plate glass to the world, as the International Style of architecture made its way to Canada. One of the country’s most famous monuments in this style is a complex of rectangular towers of black steel and dark bronze-tinted glass, the Toronto-Dominion Centre (1963–69) in Toronto, designed by the German-American architect Mies van der Rohe.

Within the world of faceless skyscrapers would come two fascinating developments. One was the virtual evacuation of the downtown area by human inhabitants after working hours. The other was the tendency of these working-hour inhabitants to turn inwards on the building complexes themselves, which were maintained at constant levels of temperature and humidity throughout the year, and contained below ground an extensive shopping mall, provision for all necessary services, and parking.

As might have been expected, the only real development strategies for Canadian cities in this period were those dominated by greed, the market, and some unspecified and almost wistful belief that progress was inevitable and would triumph in the end. City development, like most aspects of Canadian life, had been put on hold by the Depression and the war.

There was a pent-up sense within local groups of architects, planners, and developers that making new things happen was positive, even at the cost of losing links with the city’s (mostly Victorian) past. The result was the destruction of many wonderful old buildings in order to make way for new ones that were often undistinguished.

Such a trade-off was made in Toronto when the city’s first skyscraper, the majestic Temple Building of 1895 at Richmond and Bay Streets, was demolished in 1970 to be replaced by two bland towers without any public character at all. (One such threatened demolition, that of Toronto’s Old City Hall, was stopped in the 1960s as a result of a public outcry.)

In Montreal there was much more indiscriminate destruction. For example, the handsome Georgian-style Prince of Wales Terrace of eight attached dwellings — commissioned by Sir George Simpson and finished in 1860 — was demolished in 1971, to be replaced by the ungainly juxtaposition of a tall hotel and a banal six-storey building to house a department of McGill University.

Canadian cities, however, did not go so far with their bulldozers as the urban renewals of the United States and Great Britain, where hundreds of square miles of slum dwellings were razed with little idea of sensitive replacement. Canadian destruction on the whole was piecemeal rather than wholesale. One entire community, however, was demolished: Africville, an old working-class black community in Halifax was razed in 1965.

After World War II urban development in the Western world was dominated everywhere by an impatience to demolish (and relocate) old slums and ghettos, and in North America by a recognition that much of the desirable residential activity was in the suburbs. Many of the slum tenements of older cities were dreadful eyesores of deterioration, inhabited by recent immigrants and the poor; brand-new blocks of apartments, or bungalows, seemed a considerable improvement.

Not until the early 1960s — perhaps beginning with the publication of Jane Jacobs’ influential The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) — was the case made publicly that any urban renewal that destroyed existing organic neighbourhoods and communities in the process was retrogressive. Academics joined some politicians, young professionals, and citizens’ groups in insisting that any city planning that ignored the needs of people and neighbourhoods invited unforeseen damaging consequences.

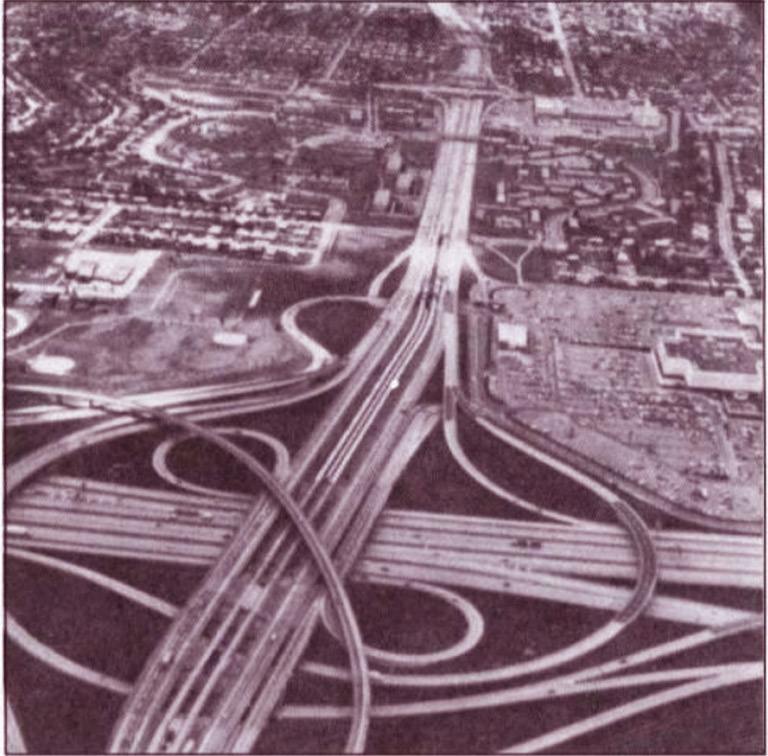

Toronto probably went furthest in its rush to modernize because of the extent of its metropolitan growth. The model planned suburb of Don Mills was developed in the early 1950s; the city was associated with twelve suburban municipalities in 1953 to form Metropolitan Toronto. In 1954 the Yonge Street subway was opened; in 1964 it was extended by the east-west Bloor line.

Toronto also built a series of bypass highways the 401, the Gardiner Expressway, the Don Valley Parkway — to enable people to get quickly from one end of the metropolitan area to another. While not quite in the same league with Los Angeles, Toronto nevertheless was thinking in the same direction in terms of a freeway culture.

With the ring-roads done, the developers moved to the inevitable inner-city connectors, such as the Spadina Expressway, which would give every resident ready access to the freeway system. But there were two problems.

One was that superhighways created new traffic as much as they relieved old bottlenecks; by 1972 bypass highways like the 401 were multi-laned traffic jams of bumper-to-bumper vehicles at first during rush hours and eventually for almost the entire day.

Improving connections between the city and its outskirts only prompted more people to move away or use the roads more frequently.

The other problem was that freeways constructed in populated areas could be built only by tearing down existing housing and devastating neighbourhoods. An extended period of Toronto opposition finally managed to stop construction of a projected expressway in 1971, which brought to a symbolic end the period of unrestricted and unplanned expansion in the city. In Vancouver at about the same time, proposals to extend the Trans-Canada Highway into the city’s centre, virtually demolishing many neighbourhoods — including the traditional Chinatown district — were fought to a standstill.

By the later 1960s citizens’ coalitions were at work in every Canadian city, attempting to control the developers who influenced most city councils and most city departments.

Urban development was orderly by comparison with what happened beyond existing settlement. New suburbs were created — usually well beyond zoning bylaws by fast-talking developers who managed to convince rural municipal councils that population growth meant jobs (rather than new taxes and a totally changed community character).

The principal attraction of the new suburbs was lower cost per square foot of house, which meant that land costs were kept down by not providing amenities (especially costly sewers) in advance. The ubiquitous septic tank (and the exceptionally green grass that grew above it) became the symbol of the true suburban bungalow.

Leaving trees up in a developing subdivision cost more in building costs than knocking them down. So down came trees, although a few developers were willing to keep them around in return for a premium price for the lot. But in most suburban developments, planting new trees and shrubs (often in areas that had only recently been heavily forested) was the first outdoor task of the new home-owner.

Drawing up for any new block only a handful of floorplans with roughly an identical number of bedrooms, floor area, and maximum mortgageable value — also saved money and made marketing easier. The number of amenities depended on price, and most builders were interested in the mass market at the lower end of the scale. The result was residential segregation based not on race or ethnicity but on number of children and ability to make mortgage payments.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

No developer regarded the suburban creation of infrastructure schools, hospitals, shopping centres, connecting roads — as part of his responsibility, and many buyers of the 1950s and 1960s would have shied away from any development whose community structure was predetermined. The trick was to sell houses to recent parents or the newly affluent — often the same people.

The typical first-time suburban buyer was a young couple with two children, partly attracted to the suburb by the Canadian love of green grass, but mostly by cost.

Marketing techniques tried to attract buyers by giving fantasy names to the developments themselves (Richmond Acres, Wilcox Lake, Beverly Hills) or to street names (Shady Lane, Sanctuary Drive, Paradise Crescent), but most newspaper advertisements concentrated on the price and down-payment required. Few buyers did much research into the surrounding amenities, most being influenced chiefly by internal house space and price.

Few suburbanites had any idea that they were the advance guard of a new Canadian lifestyle. Fewer still had had any real experience of suburbia, particularly those who were moving to developments well beyond the reach of sewers, libraries, cultural facilities, shopping, and urban transit. They had not deliberately abandoned the amenities of the city so much as they had been forced by the need for space to move beyond them. Their adjustment to new conditions became part of the major socio-cultural movement of the time.

The suburbs of the post-war period have acquired more than a bit of bad press, becoming exemplars of a vast identa-kit wasteland of intellectual vacuity, cultural sterility, and social conformity — Pete Seeger’s “little boxes.” They could be and sometimes were all those things, of course; but they were also the spawning ground of much of the revolt and rebellion of the 1960s.

The beginnings of the modern suburb can be found in eighteenth-century London, evolving gradually as “the collective creation of the bourgeois elite.” Suburbanization began as an English phenomenon, extending to North America in the nineteenth century. Europe and Latin America remained committed to their central cities, as any visitor to Paris or Buenos Aires quickly realizes.

By the twentieth century the United States had become the international centre of suburbanization. Canada lagged behind the Americans, as in so many other matters, and at least before 1945 had never previously pursued the middle-class suburb with the singlemindedness of its southern neighbours.

Although there were many examples of Canadian suburbs before World War II — such as Lawrence Park in Toronto, Westmount in Montreal, Crescentwood in Winnipeg, and Shaughnessy Heights in Vancouver — they were not normally as autonomously divorced from the urban centre as their American counterparts.

As might be expected, a resurgence of traditional domestic values after World War II was accompanied by a revival of Christian commitment, at least in terms of formal church membership and attendance. All the usual indices of revival, from attendance figures to enrolment in seminaries, increased in Canada after the war for both Protestants and Catholics.

There was no evidence that the deep-rooted problems of modern Christianity — including its identification with an outmoded morality and its reliance upon belief systems that were being challenged by secular thought — profoundly influenced increased church membership and attendance.

The religious upturn of post-war Canada, like the Baby Boom, was a temporary and largely cosmetic aberrant blip in long-term trends. Not surprisingly, much of the vitality of Christianity appeared to be in the prospering suburbs. As one observer has commented, “... between 1945 and 1966 the United Church erected 1,500 new churches and church halls, and 600 new manses — many of them handsome rambling broadloomed ranch houses.”

Suburban houses became “homes,” easily the most expensive physical object possessed by their owners. For most Canadian suburbanites, so much time and emotional energy was devoted to their house that it often seemed to possess those who occupied it. The house focused the life of the nuclear family at the same time that it permitted individual members to have their own private space.

The kitchen, for example, was seldom large enough to serve as a family room, although children of each sex were entitled to his or her own bedroom. Basement recreation rooms were developed to provide “space” for growing children. Technology increasingly turned the home into a self-regulating cocoon of constant temperature and convenience.

Most consumer investments added new furnishings and appliances, not all of which were immediately visible to the stranger. The replacement of coal with oil and gas furnaces governed by thermostats, the introduction of automatic hot water heating, even the beginning of domestic air-conditioning, all insulated the inhabitants from an earlier world in which domesticity required hard work and constant vigilance.

Now air temperature could almost be taken for granted — no mean accomplishment in the harsh Canadian climate. Those suburbanites who worried about “getting soft” assuaged their concerns with summer camping-trips and roughing it at the cottage.

Life in suburbia depended on a clear understanding of family roles. Husbands were the breadwinners, often working far away from the home, while their wives were actually responsible for its daily functioning.

Most Canadian women had chosen — at least at war’s end — to remain out of the work-force in order to enjoy marriage and child-rearing. They were reinforced in their decisions by articles in the women’s journals exalting the roles of housewife and mother, and by advertising that appealed to their domesticity.

At the same time that many women made “careers” as housewives and mothers, the sociologists of Crestwood Heights: A North American Suburb (1956) — a study based on Forest Hill Village, a wealthy residential area in Toronto — found a good deal of ambivalence over this decision and the values underlying it:

The career of the woman in Crestwood Heights, compared with that of the man, contains many anomalies. Ideally, the man follows a continuous, if looping, spiral of development; the woman must pursue two goals and integrate them into one.

The first goal has to do with a job, the second with matrimony and motherhood. The second, for the woman, is realized at the expense of the first; the man’s two goals combine, since matrimony is expected to strengthen him for his work, and at it.

Even younger women away at university were confused. One confessed to an interviewer:

“Why I want to work — because I hope to express my personality through struggle and achievement. Why I want to get married — because my real role in society is that of wife and mother. If I don’t get married, I will feel insecure— I will have no clearly defined role in society. I will probably sacrifice career to marriage if the opportunity comes because the rewards of marriage are obvious, those of a career uncertain. In a way I envy those girls who only want to get married. They don’t have to equate two conflicting desires.”

For the female, suburbia was often little more than an arena in which this conflict was continually acted out.

Central to any suburban household were its children, around whose upbringing the lives of the parents increasingly revolved. The baby-boom generation of children were brought up in a child-centred environment, particularly in the home. Older standards of discipline and toughness in the parent-child relationship were replaced by permissiveness.

New childrearing attitudes were influenced by all sorts of factors, but found their popular expression in The Pocket Book of Baby and Child Care by Benjamin Spock, M.D., which outsold the Bible in Canada in the years after the war. Many Canadian and American mothers referred to Spock as “God.”

Canada had its own semi-official child-care manual, The Canadian Mother and Child, by Ernest Couture, M.D. director of the Division of Child and Maternal Health of the Department of National Health and Welfare — which was distributed free by doctors to pregnant women.

It was a forbidding and austere grey-covered book, filled with slightly out-of-date photographs and a prim, no-nonsense style, Couture’s advice to fathers was typical. They needed to accompany their wives on first visits to the doctor at the beginning of pregnancy; to understand what prenatal and postnatal care meant; and to adopt an attitude that was “patient, kind, and forebearing” during pregnancy, for women suffered from mood changes they were “quite unable to control.”

He also stressed cleanliness and good sanitation for the home: “Plumbing and drainage should be kept in good condition. Nothing is more destructive to a home, and to health, than leaky pipes and drains.”

Small wonder Canadian parents, at least in English-speaking Canada, preferred the folksy conversational approach of the American expert to the bleak advice of the Canadian.

The triumph in Anglo-Canada of Dr. Spock over Dr. Couture says a good deal about Canadian versus American style in the realm of culture. The Canadian approach was firmly elitist, with useful information produced at the top and trickled down to the potential “client.” The American approach was frankly democratic and commercial, with useful information mass-marketed to the “consumer.”

Spock’s book was one of the earliest mass-marketed paperbacks and sold over the counter at drug stores and supermarkets. In its pages the reader could find continual reassurance. “Use your common sense,” said Doctor Spock, “for almost anything reasonable is okay.” “Trust Yourself” was his first injunction.

The good doctor came down fairly hard against coercion and forcing of the child, however. He was against early toilet training, for example, arguing, “Practically all those children who regularly go on soiling after 2 are those whose mothers have made a big issue about it and those who have become frightened by painful movements.”

While Spock seldom was this categorical about any child-rearing strategy adopting a non-prescriptive position on breast-feeding versus bottle-feeding, for example he was certainly not, in early editions, enthusiastic about working mothers:

The important thing for a mother to realize is that the younger the child the more necessary it is for him to have a steady, loving person taking care of him. In most cases, the mother is the best one to give him this feeling of “belonging,” safely and surely.

She doesn’t quit on the job, she doesn’t turn against him, she isn’t indifferent to him, she takes care of him always in the same familiar house. If the mother realizes clearly how vital this kind of care is to a small child, it may make it easier for her to decide that the extra money she might earn, or the satisfaction she might receive from an outside job, is not so important after all.

At the same time, Spock had more encouraging words for fathers than Doctor Couture, emphasizing that “You can be a warm father and a real man at the same time” while adding that it was “fine” for Dad to give bottles or change diapers “occasionally.”

In opposing over-structured child-rearing practices, Spock may well have gone too far. But the post-war Canadian mother came to rely on his commonsensical advice. He saw that children passed through stages, and that once parents recognized what stage their child had reached, they could appreciate that seemingly incomprehensible behaviour and problems were quite common.

Spock’s chapter on the adolescent, “Puberty Development,” dealt with the sexual maturing of children, emphasized their awkwardness, and pointed out that most girls reached puberty two years ahead of boys. A full page was devoted to “Skin troubles in adolescence,” particularly the pimples that the patent medicine folks labelled “teen-age acne.”

Spock was for washing the skin and against squeezing, which probably helps explain the folk wisdom of the era about those ubiquitous pimples. For suburbia, however, the adolescent was more than merely a creation of puberty. The “teenager” represented the emergence of a new generation that coincided with the maturing of the baby-boomers.

Both the elongation of the adolescent stage and its general significance took on new meaning in the two decades after the war. A general extension of the school-leaving age (and the expectation of suburbia’s parents that children would continue their education beyond legal requirements) combined with the new affluence and permissiveness to produce large numbers of adolescents with considerable spending power.

In English-speaking Canada teenagers became avid consumers — a recognizable market for fast food, popular music, acne medicine, and clothing fads.

For the new term “teenager,” an English-language neologism, there is no equivalent in French. Obviously “adolescence” — the word is the same in both languages — does not carry the same cultural freight. French Canada has never had a “teenage problem,” but rather a “problème de jeune,” a quite different matter.

It has also tended to view the suburb in physical rather than in cultural terms. In the autobiographical Nègres blancs d’Amérique (1968) / White Niggers of America (1971), the radical Québécois Pierre Vallières (b. 1938) — who was jailed on charges connected with his FLQ activities and wrote his book in prison — suggests that men like his father had their own suburban fantasies:

If only Madeleine [Vailières’s mother] can agree to it, he said to himself.... We’ll be at peace. The children will have all the room they need to play. We’ll be masters in our own house. There will be no more stairs to go up and down.... Pierre won’t hang around the alleys and sheds any more.... The owner was prepared to stretch the payments out over many years.... Life would become easier. ... He would enlarge the house. A few years from now, Madeleine and the “little ones” would have peace and comfort.

And so in 1945 the Vallières family moved to Longueuil-Annexe: “the largest of an infinite number of little islands of houses springing up here, there, and everywhere out of the immense fields which in the space of a few years were to be transformed into a vast mushroom city.”

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!