Being a Newfoundlander in Canada

Back when I thought it was better to pretend to know things than to ever let on that I didn’t know something, the CBC called and asked me to give the Graham Spry lecture. I was thrilled! What an honour! Of course, I had no clue what on earth the Spry lecture was, or what I was supposed to know or do to deliver one. But at that point I felt it would be highly insulting to this wonderful person who had conferred such a great and glorious honour on me to ask what the Spry lecture was supposed to be, or even if it was good to eat.

Feeling that query would reveal me as the ignorant know-nothing I knew I was — and loosely based on the fact that it was the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), and that Graham Spry had been a Canadian of some note — I surmised, totally incorrectly as it turns out, that they were asking me to give a lecture about Canada, or maybe the history of Canada. Yes, I thought, it must be that.

Now, it was 1992, I was forty years old, and Newfoundland had joined Canada forty-three years before; but despite all that I knew next to nothing about the history of Canada. Of course, right away I blamed that on myself — because I had learned at my mother’s knee (or, rather, at the metal knee joint of my aunt’s wooden leg) a great resentment for Canada and all things Canadian.

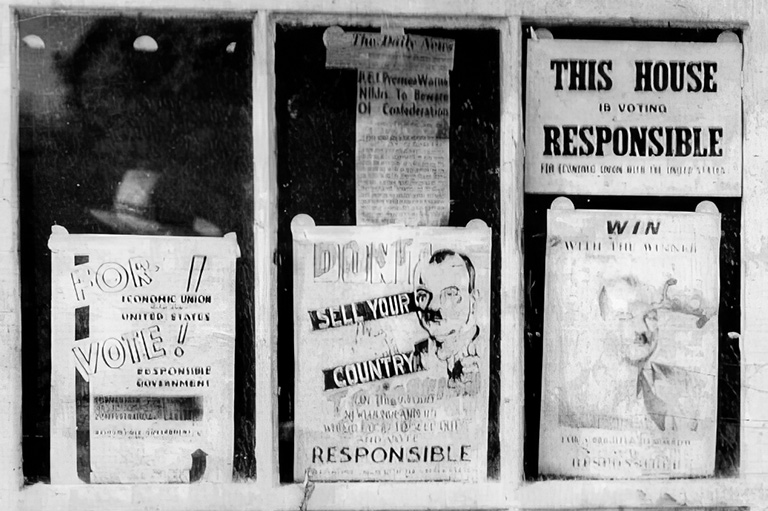

During the referendum on July 22, 1948, almost fifty per cent of the people of Newfoundland, and I wager all the people of St. John’s, voted against Confederation with Canada. St. John’s voted overwhelmingly in favour of a return to responsible government. We lost that vote, and we went from being a protectorate of England — in the dirty thirties, Newfoundland had given up her right to selfgovernment, and six commissioners had been appointed by the British government, and these six commissioners, along with a British-appointed governor, governed Newfoundland — but, as I was saying, we went from being a powerless colony of Great Britain to becoming the youngest and poorest province in Canadian Confederation; from being England’s doormat to being Canada’s laughingstock.

I was born in 1952, and during my childhood anti-confederate feelings ran very high. There was no end to complaining about the shoddiness of Canadian goods, the dour and cheap nature of the Canadian heart.

I didn’t even really run into a Canadian until about grade five, when Janet, a girl from Toronto, came into our class. She had four sisters, a father who had a “big job” with the federal government, and a mother who worked, and they had a maid — all pretty heady stuff for my crowd of Newfoundland ten-year-olds. But the truly memorable thing about Janet was the nose cosy her grandmother in Winnipeg had knit and sent to her to protect her delicate Toronto nose from the harshness of the St. John’s winter.

Well. We, the other grade fives, resented the implication immensely. We saw it as a direct slap in the face to Newfoundland, and of course to us. Who did they think they were? Where did they think she was living? Oh God, we were incensed. And so we gave Janet quite a lot of fairly vicious tormenting. Poor Janet: She was stuck with wearing that ridiculous nose cosy, of course. (For those of you not familiar with the nose cosy: It is a knitted object, roughly the same shape as the nose, with, of course, two nostril holes and two strings that go from the cosy and tie around the back of the head to keep it snug.) And she had to wear it every day that winter. Poor Janet, indeed.

And then, you know, I don’t remember meeting or seeing any other Canadians. There were Portuguese, Spaniards, Russians, Poles, Americans off the ship, and you’d see all of them down on Water Street, but I don’t remember any Canadians. And in school, except for Janet, it was just basically us. The us sprung, as satirist Ray Guy always said, from a genetic pool the size of a pudding bowl.

My next encounter with Canadians didn’t go much better. I moved to Toronto to attend theatre school, lived in a house full of homesick and lonely Newfoundlanders, and we were all determined to make Canadian friends or die trying. There was a communal houseload of them right across the street from us, and on these Canadians we set our friendship sights. We planned to pay them a surprise visit one Friday night, but being young, nervous, and socially inept we thought we’d have a few drinks first — to make us feel more at ease. We had a lot of drinks, actually, and then went over to their house, and we talked at them quite a lot, and then we threw up quite a lot, and then we finally left. We always saw it as proof positive of the essential minginess and coldness of the nature of the Canadian that they never tried to contact us again.

I was surprisingly Canadian-free during my formative years, and when I began to tour Canada with the comedy troupe Codco in the mid-seventies I was always confounded at Canada’s insecurity, at that time, about its identity. Canadians all across the country seemed to be so obviously and so recognizably what they were, Canadians, and they seemed to share many things and hold many common beliefs, one of them being an overwhelming certainty that they were so much better than us “goofie Newfies,” as we were referred to so often then. I never fully understood Canada’s struggle to forge an identity, because we always knew who Canadians were: people who thought they were so much better than us.

So, in order to write the Spry lecture, I came to the desperate conclusion that I had to do a crash course in Canadian history. I headed over to St. Mary’s University in Halifax and read everything I could get my hands on. I was left with a sense that most Canadians weren’t that interested in their history, that Canadian history was thought to be kind of boring, that not that much had happened in Canada, really, it was just all Peace, Order, and Good Government, yawn, yawn, yawn. And that sentiment continues to this day.

I have no idea why a country would choose to ignore and to not celebrate its own history. I mean, surely the story of seven-year-old John A. Macdonald bravely trying to save his five-year-old brother from a drunken babysitter, and then being forced to watch that brother being beaten to death with a cane, is, while not particularly uplifting, undoubtedly as interesting as, if not way more so than George Washington’s “I chopped down that cherry tree.”

And Louis Riel, surely a hero in all the official languages. I mean, isn’t Riel worthy of at least as much recognition and celebration as Davy Crockett? And yet we seem to know much more about Davy Crockett than we do about Riel. Why had I never heard of Chief Peguis, who saved the lives of settlers brought to the Red River area, now called Winnipeg, by Lord Selkirk? One story goes that when the main group of settlers arrived they found that none of the promised gardens had been planted, nor the houses built. Winter was coming, and Peguis, and the members of his Saulteaux Nation, brought those settlers to their camp and kept them alive over the winter, fed them, and showed them how to hunt buffalo and work the land. Yes, without Peguis and his nation, there might be no Winnipeg.

I realized then that I wasn’t the only Canadian ignorant of our history, and that our ignorance almost appears to be wilful. Where is our heroic origin story? We’ve never made those “myth of conquest” films that allow us to look at the stealing of this land as great and inevitable. Unlike the United States, we don’t seem to have articulated a heroic myth.

Where are our Canadian epics? Our civil religion of Canadianness? Perhaps by ignoring all our history, even the good parts, we can ignore the mistakes, poke them away, not focus at all on the past, neither mythologize nor celebrate, just ignore and dismiss with the excuse that it’s all too boring. Perhaps we’re unable to face all of the mistakes that we did make — for example, calling what those explorers from France and England did “discovering” this country, as opposed to “invading” this country. As everyone knows, it is almost impossible to discover a place that is already fully occupied.

As a people, have we just been too practical, too steadfast, too steady to indulge in all of that overhyped mythmaking, and so have been mercifully spared the horrors of a Canadian The Birth of a Nation, that notorious American cinematic epic with all its filthy racism and ugly celebration of white supremacy? Or maybe Canadians believe what the German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel said, that all that history has taught us is that we learn nothing from history.

But Canada’s great genius Northrop Frye claimed that we learn everything from our geography, that a people is formed by its geography, that where we are makes us who we are. And just look at where we are: Every inch of this country is awe-inspiring. And geography? I mean, we are rotted out with geography. We’re practically choked on oceans; we’ve got three of them. We’ve got that big aweinspiring Arctic, that huge northern mystery, always looming up there behind us, and nine million, nine hundred and eighty-four thousand, six hundred and seventy square kilometres of good earth — the second-largest land mass in the entire world.

And if Frye is right, and a people’s character is formed by their geography, then our character should be enormous, bighearted, bountiful, beneficent, because here we are, a people faced with an embarrassment of geographic riches. We have so much, so much room, so much room to be, to be accepting, to be tolerant, to throw open our arms, to be generous. Room to celebrate all the things we did right, and room and time to fix all the mistakes we made in the past. Room to be large in our dealings with the world and with each other.

According to John Ralston Saul, everything we celebrate as good about Canada we learned from our initial two-hundred- year peaceful relationship between settlers and Indigenous people. In a startlingly original vision of Canada, the renowned thinker argued that our institutions and common sense as a civilization are more Indigenous than European, and that all of the best of Canadian egalitarianism has been heavily influenced and shaped by Indigenous ideas. And as the painter Emily Carr said, “It is wonderful to feel the grandness of Canada in the raw, not because she is Canada but because she’s something sublime that you were born into, some great rugged power that you are a part of.”

The old saying “familiarity breeds contempt” worked in the total opposite way for me, and for my feelings about Canada and Canadians. The more time I spent in this beautiful, forbidding, glory of a country, the more grateful I was to be part of it.

Road to Confederation

Inhabited for thousands of years by Indigenous peoples, the area now known as Newfoundland and Labrador was briefly settled by Vikings around 1000 CE and later used by European fishermen and whalers for shore stations beginning in the 1500s. In the ensuing centuries, settlers established villages, and England and France fought over fishing rights and imperial control. France gave up its colonial claims in 1713 but retained some fishing rights until 1904. In 1825, due to the large number of permanent English and Irish settlers, Britain changed Newfoundland’s status from a fishing station to an official colony. Several events led to Newfoundland (which included Labrador) joining Canada on March 31, 1949.

1832

The colony is granted representative government. Although an elected House of Assembly is formed, most power is held by the Britishappointed governor and his hand-picked legislative and executive councils.

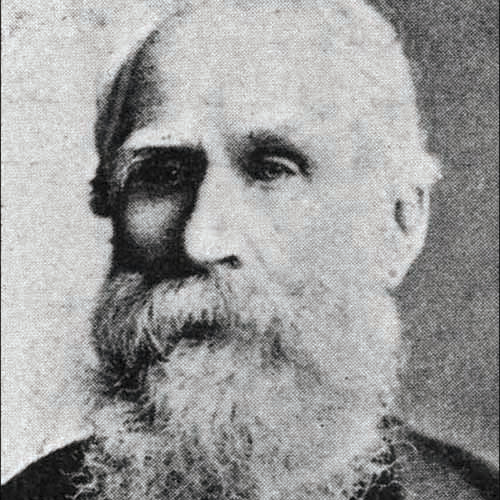

1855

Newfoundland achieves responsible government, with power shifting to the elected House of Assembly. Philip F. Little (left) is elected premier.

1869

Two years after the Province of Canada unites with New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, Newfoundlanders vote on whether to join Confederation. They soundly reject the idea.

1931

Following the sacrifices of the First World War, the Statute of Westminster declares the Dominion of Newfoundland an equal and independent nation within the British Commonwealth.

1929-34

The First World War and the construction of a railway had saddled Newfoundland with enormous debt, owed mainly to Canadian banks. Political scandals and the Great Depression made matters worse. Facing bankruptcy, the Newfoundland legislature in 1933 votes to dissolve itself. Britain appoints a Commission of Government with a governor and six commissioners to temporarily rule the Dominion.

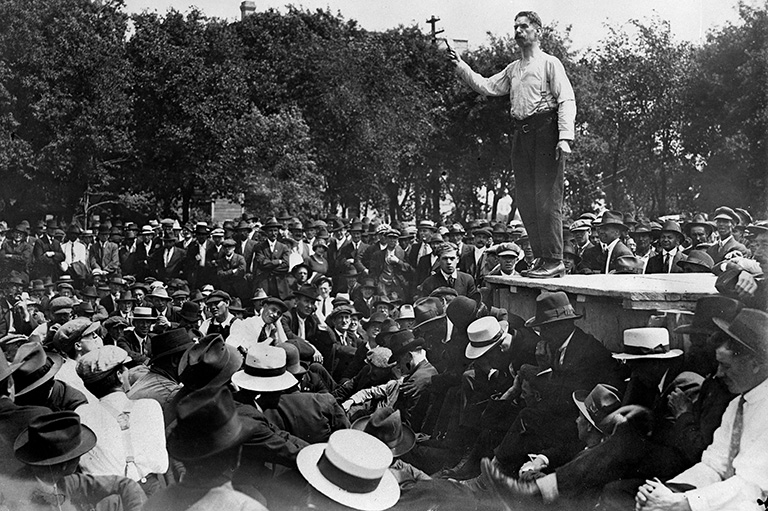

1948

Newfoundland holds a referendum on governance on June 3 with three options: continuation of the Commission of Government, return to responsible government, or Confederation with Canada. The Commission of Government option receives the fewest votes and is dropped from a second referendum on July 22. A slim majority of 52.3 per cent of voters favours Confederation.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!