The Twisted Genius of George Feyer

At a formal dinner an angry man chokes a fellow diner with one hand. In the other he’s holding a fork, ready to strike. Before he can finish the job he’s started, his wife butts in, “Henry, Henry! That’s the wrong fork.”

Mary and Joseph walk out of a pharmacy with an ad for pregnancy tests in its window. Appearing beatific, Mary strides along with a halo perched over her head. Her aggrieved husband mutters to himself, “Bullshit.”

A little girl strolls away from a department store Santa Claus who is sitting dumbstruck in his chair. Off-panel an adult is shouting to the girl, “Lolita! Let’s go!!”

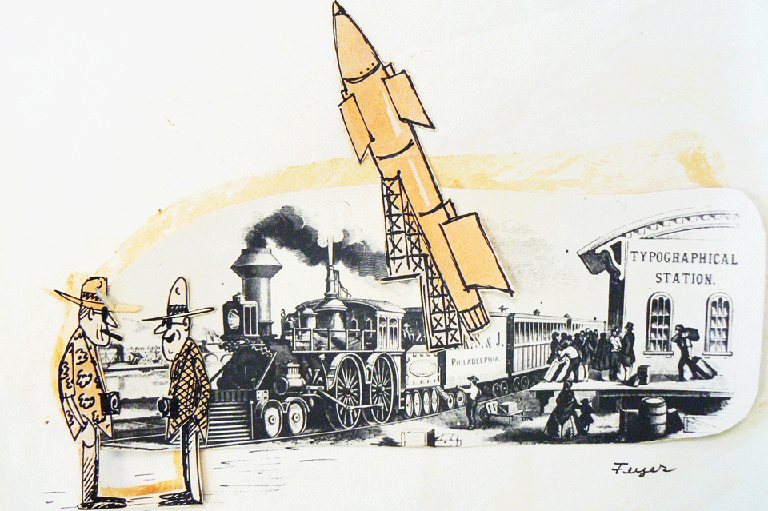

Each of these ideas originated more than fifty years ago in the brilliant and bizarre mind of George Feyer, a tragically shortlived giant of Canadian cartooning. Equal parts madman, genius, imp, and intellectual, Feyer was a one‐of‐a‐kind artist whose body of work defies categorization.

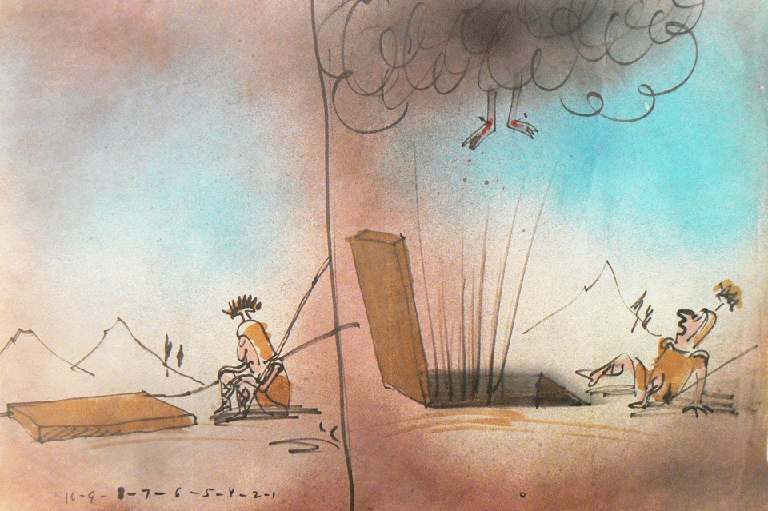

His initial burst of fame came thanks to his incisive gag cartoons, which cut through the pretentions and hypocrisies of 1950s North America — often without the benefit of a single word. Between 1949 and 1967, Feyer drew hundreds of cartoons for more than forty publications around the world, including Collier’s, Punch, Maclean’s, the Globe and Mail and the Toronto Star. Yet cartooning was just one manifestation of his relentless, irreverent talents.

Over the course of his eighteen‐year career, the polymathic Feyer wore many hats. He was a nationally known television personality — thanks to dozens of appearances on shows such as Hockey Night in Canada, Wayne and Shuster, and The Danny Kaye Show — a much‐loved children’s entertainer as a result of his work on CBCTV, the owner of several patents for innovative animation techniques, the creator of a line of sophisticated gag gifts (like a birth-control alarm clock), and a member in good standing of Toronto’s mid-century cognoscenti club, a role that saw him hobnob with the likes of Marshall McLuhan, Peter Gzowski, George Jonas, June Callwood, and Pierre Berton.

Small in stature and raunchy by inclination, Feyer was part of a wave of Hungarian intellectuals, artists, and writers that immigrated to Canada in the years following the Second World War. Like many of his countrymen he was highly motivated and wasted little time constructing an eclectic and eventful career that was unprecedented in his day — and possibly unrivalled in ours.

Berton, a frustrated cartoonist himself, was magnetically drawn to the diminutive whirlwind. In an article published in the wake of Feyer’s death in 1967, Berton praised his friend as “the most inventive man I have known,” adding that “ideas crackled from George in meteoric showers.”

Decades before British graffiti artist/ prankster Banksy stole his first can of spray paint, Feyer was known for his penchant for drawing on anything — and anyone — with his ever-present felt-tipped marker. Hotel walls, ceilings, floors, doors, toilets, sinks, mirrors, women’s backs (and their chests and stomachs), even his best friend’s bald head, all received the Feyer touch. In the words of Berton, “it was impossible for George to pass so much as an elevator button without turning it into a cartoon.”

To Feyer, life itself was a form of art, and everything was his canvas.

With a fearless world view that predated the underground cartoonists of the 1960s — such as Robert Crumb, Frank Stack, and Gilbert Shelton — and an innovative European style that stood up next to the likes of Saul Steinberg, Jules Feiffer, and Harvey Kurtzman, Feyer’s future should have been secure. But it was not to be.

Attracted by the promise of fresh opportunities and a chance to work with some of the brightest minds in Hollywood, Feyer traded Canada for California in 1965 — with very tragic results. “He died in the prime of his life, at the peak of his career,” Berton lamented.

As tragic as his death was — he left behind an ex‐wife and a seven‐year‐old son — the grander tragedy may be that, outside of family, friends, and a clutch of cartoonists, George Feyer and his epic body of work remain virtually unknown to Canadians.

György Feyer was born on February 18, 1921, in Budapest, Hungary, the only child of a lawyer father and a social-worker mother. Though he was brought up Roman Catholic, Feyer’s mother was Jewish, which granted him Jewish status in the eyes of Judaic tradition.

Almost a year to the day before Feyer’s birth, Miklós Horthy, a right‐wing ideologue and well‐known anti‐Semite, seized power in Hungary, booted out Communist forces, and installed himself as head of state and regent. Horthy wasted little time implementing legislation that capped Jewish enrolment in universities at five per cent. It would be the first of many such laws to come.

These were tumultuous times, and they played a critical role in shaping Feyer’s world view.

When he was a young boy, Feyer’s parents divorced and later remarried other people. “I had two fathers and two mothers. I loved them all, and they were all very friendly,” Feyer told McKenzie Porter in a 1960 profile in Maclean’s magazine. “They were liberal intellectuals. They hated soldiers, flags, priests, nationalism, and all that chauvinistic stuff. And so did I. That’s why I had such an unhappy time at school.”

Being raised half‐Jewish by four progressive parents in an increasingly fascistic country made for a unique and difficult childhood. On one hand he enjoyed the benefits of privilege; his father’s money and status brought him education and respect. Feyer once recalled visiting his father’s ancestral property in the Hungarian countryside and having to stop to allow peasants to kiss his nine‐year‐old hand.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

But he also spent part of his childhood living with his mother in one of Budapest’s Jewish neighbourhoods. Small and with a limp that resulted from a childhood illness, Feyer made a handy target for bullies — anti‐Semitic or otherwise.

Elsa Franklin, Berton’s long‐time producer and literary agent, said that, despite Feyer’s reputation as a charming imp, “he was quite a serious man. And I think his background had a lot to do with it: He was half‐Jewish, and he came from Hungary. I think he was always troubled, and I think he suffered.”

Feyer’s predicament worsened with the ramping up of German‐ and Italian‐styled fascism in Hungary during the 1930s.

“At school the other boys marched up and down and followed the flag,” Feyer told Maclean’s. “But I said to myself, ‘To hell with the flag.’ By the time I was fifteen I was suffocating under the bombast, the bureaucracy, and the despotism of life in a central European country.”

It was a resentment he would harbour for the rest of his life. According to Berton, Feyer “had a love‐hate relationship with his native land.” During his annual summer vacations there he would complain loudly about the country and its people, reserving a special hatred for the traditional gypsy music of his homeland.

Already with a well‐established distaste for politics, it wasn’t long before the young Feyer developed an aversion for organized religion as well. In a 1984 interview with June Callwood, Feyer’s widow Michaela said that as a teenager he had been enrolled by his parents in a Jesuit boarding school. Priests at the private school “beat him so severely he screamed with nightmares for the rest of his life,” she said. A year later he ran away from the school — and religion — for good.

Feyer’s atheism, combined with his distaste for politics and nationalism, was the perfect recipe for the fiercely iconoclastic world view he carried with him for the rest of his years like a talisman.

“He was anti-communist, anti-fascist and anti-establishment, and he had the credentials to prove that these attitudes were not poses,” Berton said. “If you asked him what his politics were, he generally replied that he was a survivor.”

As a teenager Feyer began submitting cartoons to political magazines and newspapers in Hungary as a way to express his political views. To his surprise he got published — at the age of fifteen — and paid. His work was so advanced that editors didn’t cotton on to the fact that he was just a teenager and paid him the standard adult fee. Suddenly “I was rich, [and] the other kids hated me for it.”

The earliest known example of Feyer’s cartooning appeared around 1936. Its subject was “Gloomy Sunday,” a popular (and peculiar) Hungarian song about a man longing to reunite with his dead lover on the other side of the veil.

First recorded in 1935, “Gloomy Sunday” was a perverse No. 1 hit. The song’s melancholy tune and maudlin lyrics proved so popular that it spawned a rash of sympathetic suicides. Lovesick men and women jumped into the Danube River with copies of the song’s sheet music stuffed in their pockets.

The effect was so pervasive that Hungarian authorities reportedly banned musicians from performing the song in public. (The grim legacy of “Gloomy Sunday” had a long reach. In 1968 the song’s composer, Rezső Seress, tried to kill himself by jumping out of a window in his Budapest apartment. The seventy-year-old survived, only to finish the job later in a hospital where he choked himself to death with a wire.)

Feyer’s strip was titled “Chanson Triste” (“Sad Song”) and wordlessly depicts what happens when two musical notes come to life on a piece of sheet music. The male note tries to woo the female note and is rebuffed. Heartbroken, he slinks away, cuts a length off of one of the staffs, and hangs himself with it.

Feyer’s cartoon spoofs the song on at least two levels: one by poking dark fun at the terminal lengths that notoriously depressed Hungarians were willing to go to express their devotion for “the suicide song”; and, more interestingly, by suggesting that the song was so sad that it had the power to bring its musical notations to life, just so they could kill themselves. By any measure, a sophisticated send-up — fifteen- year-old boy or not.

Feyer continued to earn a living as a cartoonist throughout the 1930s, even as Hungary’s fascist government passed bill after bill in its increasingly anti-Jewish doctrine.

“Satire has always flourished under dictatorships,” he explained later of his work at the time, “[but] you have to be very subtle. Each drawing has to have two or three meanings so that you can plead the most harmless one if the cops come to carry you off to jail.”

When war broke out in the fall of 1939, his bum leg helped the nineteen-year-old Feyer avoid conscription in the Hungarian army. Over the next few years he managed to steer clear of it in a series of inventive ways — by masquerading as a small boy, wearing a fake cast on his leg, and, once, by faking insanity.

But by 1943, with Hungary officially aligned with Axis powers, the young cartoonist was finally recruited to fight the Russians on the Eastern Front. He lasted a year. The end came one night when Feyer was walking and came across a stack of corpses piled several metres high, illuminated only by moonlight.

“He stared in horror and noticed that the whole mound was stirring slightly,” Porter wrote in Maclean’s. “Going closer he discovered that it was crawling with rats.” The next day Feyer started planning the first of many of his escapes.

Using his cartooning skills he forged a series of documents, each one designed to gain him passage with the sixteen military officials and bureaucrats that he knew stood between him and his home. He then exchanged his fatigues for civilian clothes and, posing as a disabled sixteen-year-old, walked some 1,500 kilometres (a month of twelve-hour days for an able-bodied person) back to Budapest.

Not that life in the increasingly fascistic and violently anti-Semitic city was going to be any easier for a half-Jewish army deserter. “For two years I looked out a window,” he told Maclean’s, only leaving his garret to fetch food and supplies.

For money he tracked down art supplies and rubber stamps and set up a lucrative business forging passports and birth certificates. His clients included escaped prisoners of war, fugitive Jews, AWOL soldiers, and fleeing politicians — “Every so-called enemy of the state,” as he put it. “I hated the whole war so much that I didn’t give a damn who I helped to get out of it. It was a case of every poor devil for himself.”

In March 1944 Germany invaded Hungary and installed a head of state who made the anti-Semitic policies of Miklós Horthy seem progressive. By May the new government was transporting twelve thousand Jews a day by rail car to the camps at Auschwitz.

According to historian Krisztian Ungvary, the pace was so frenzied that by October “the only Hungarian Jews not in concentration camps were those in Budapest and in forced labour camps.” Feyer was one of the lucky ones, for the time being.

By December Russian forces had encircled the capital city, launching the Siege of Budapest, a brutal and bloody hundred-day battle in the dead of winter that placed 800,000 Hungarian civilians in the crossfire. According to Ungvary’s The Siege of Budapest, food supplies quickly ran out. People scavenged for food in heaps of garbage, fed off dead cavalry horses, or hunted exotic animals that had escaped from the bombarded Budapest Zoo.

Those civilians who didn’t die of hunger, cold, or disease perished in military actions or through anti-Semitic violence. Hundreds of Jews were publically executed — often in broad daylight — by everyday Hungarians. Men, women, children, and even priests took part. At one point senior Nazis advised Hungarian officials to rein them in, fearing a public backlash. By the time Budapest fell to the Russians on February 13, 1945, more than 150,000 people were dead, including 38,000 Hungarian civilians.

In the middle of this maelstrom went Feyer and his family.

Feyer never wrote about the siege and rarely discussed it with friends or family, but its effects were undeniable. On a tour of Hungary he and Berton took in the 1960s Feyer confided that “the Hungarians were worse to the Jews than anybody, including the Nazis.”

Later, when Berton asked him why he hadn’t written about his wartime experiences, Feyer “simply said [to Berton] ... that they were so unbelievable nobody would believe them.”

According to George Jonas, a fellow Hungarian who was friendly with Feyer, the cartoonist “had demons of all kinds. If you talked with him for five minutes, you’d know he was a guy who had a dark side.”

After the war, Feyer stayed in now Soviet-occupied Hungary, making ends meet with his forgery business and the occasional freelance job. In 1946, when the Communists began to clamp down on the black market, Feyer packed up his gear, walked to Vienna, and surrendered to British forces.

He briefly lived in a displaced persons camp before leaving and settling in Munich, West Germany, where he took to cartooning again full-time. Soon his mother joined him, and the pair resolved to emigrate to the West. His father remained in Hungary.

“Coming to America is the dream of almost all immigrants, and that was my dream too,” Feyer told CBC-TV in 1964. “Capitalism always appealed to me.”

But his initial attempts to gain entry to the United States were unsuccessful, he claimed, because of anti-Semitism. Though the border was not protected by guns or “towers with search lights,” he said, “it’s strong enough to exclude ninety per cent of the human race: mainly those who don’t match the colour scheme.”

Pierre Berton praised Feyer as “the most inventive man I have known,” adding that “ideas crackled from George in meteoric showers.”

Turned back by the U.S., Feyer and his mother applied to Canada. She was accepted right away. It took George, now twenty-seven, five attempts, in part because officials considered his leg injury a disability. He finally won entry — as he would many times during his life — by the well-timed execution of his expertly engineered wit.

On his fifth attempt he covered his immigration application with cartoons of himself drawn as a strapping lumberjack, chopping wood and generally being a productive member of Canadian society. The immigration officers were amused and approved his application.

Knowing only a few words of English, Feyer arrived in Toronto in 1948, got an eighteen-dollar-aweek job in a quilt factory, and moved into an attic on Spadina Road. When he wasn’t stuffing duck feathers into quilts, he was drawing comics and cartoons.

In 1949 he sold his first comic, a simple gag about a man visiting his optometrist, to Maclean’s. But the real joke was squirrelled away in the background, where he had hidden a series of Hungarian profanities in the optometrist’s chart — a dirty and sly in-joke for his fellow countrymen. The sale, the first of many to come with the magazine, was a godsend. “I came to life again,” Feyer said.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Over the next few years Feyer published scores of cartoons, many of which were syndicated internationally. His style blossomed, evolving from a static line to his signature loose “cartoony” style, seemingly influenced by visually innovative European cartoonists such as Saul Steinberg, André François, and Maurice Sinet, known as Siné.

Cartoonist Terry Mosher — who works under the pen name Aislin — remembers Feyer’s work in Maclean’s, which he read growing up in Montreal during the 1950s. “They were certainly a lot more interesting than the bland cartooning that was appearing elsewhere.”

“There’s a lot of good competent cartoonists who give you a laugh sometimes, though not all of the time. But there are those people who stand out, and George is one of them,” said Mosher. “In terms of my own personal ranking, he’s right up there in the upper echelon. If you’re thinking of the original six teams in the NHL, he’s one of them.”

Seth — the pen name of award-winning Guelph, Ontario, cartoonist Gregory Gallant — discovered Feyer’s work by accident twenty years ago while flipping through a collection of international gag comics.

“As a Canadian, your first response when you see anything from Canada is that you just hope it’s not embarrassing,” he said. “So it was nice to see that he was — to use a horrible phrase — a world-class cartoonist. George was doing a much more sophisticated kind of cartooning than anybody in Canada. … And I was kind of disappointed that I had no idea who he was.”

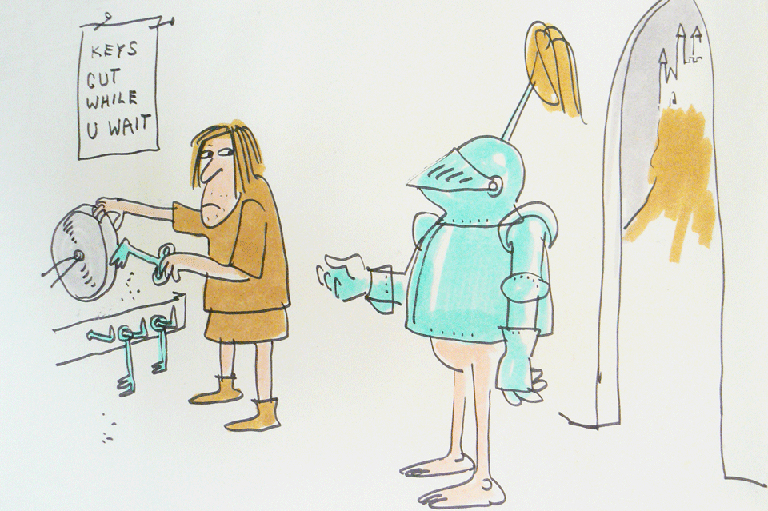

What makes Feyer’s comics stand out, in Gallant’s eyes, is that “every cartoon by Feyer features mischievous characters. And he doesn’t do sweet; his characters were always manic, and I think if he had been allowed a little more freedom, they would have been dirtier, too.”

By 1951 Feyer was making enough money with comics to quit his job and move into a bigger, better apartment and rent a nearby apartment for his mother. That summer he met Michaela Fitzsimons, an art student who was home on a study break. George spotted her at a party north of Toronto and pursued her with his signature devotion.

For two weeks he called her precisely at 11:30 every night and played romantic records over the receiver. On the last night, when Fitzsimons picked up the phone, Feyer said, “How do you like my music?” They were engaged four days later.

It was around this time that Feyer met the man who would be the second-most-important relationship in his life.

The writer Pierre Berton had moved to Toronto a year before Feyer and within a couple of years had ascended to managing editor of Maclean’s, which is where he was introduced to Feyer and his work. Though they seemed an unlikely pair on the surface — Berton was more than six feet tall with a trademark sonorous voice; Feyer was five feet, six inches and congenitally softspoken — the duo actually had a lot in common.

Born just seven months apart, both served in Europe during the war, each harboured strong anti- establishment leanings, and both appreciated the unique alchemy of words and images called comics.

Though Berton is best known as an author and TV personality, he grew up a diehard fan of comic strips and editorial cartooning and originally aspired to a life behind the drawing board. He even tried his hand at cartooning in student papers at university in the 1930s, to little success.

“Berton was a frustrated cartoonist, as a lot of people are, like Margaret Atwood,” Mosher said. “But,” he joked, “they couldn’t make it, so they moved on to lesser things.”

Though Berton switched to journalism after graduation, his passion for comics remained. In the 1940s, as an editor at the Vancouver Sun, he gave cartoonist Len Norris his start, and later he helped launch the careers of Canadian cartooning giants Duncan Macpherson and Sid Barron. “Pierre Berton should be remembered as a patron saint of the golden age of Canadian cartooning,” said Mosher.

Pretty soon Berton was introducing Feyer to his associates in Toronto, which included Marshall McLuhan, June Callwood, Peter Munk (a fellow Hungarian émigré), Norman Jewison, CBC Radio’s Allan McFee and Lister Sinclair, among others.

“He chewed it up,” said Mosher. “He moved through Toronto’s establishment like a strong wind. It was phenomenal. He thoroughly enjoyed the fame in Toronto, there’s no question about that. These big magazine articles were written about him, and the cream of Toronto society was fawning over him.”

As a member of Toronto’s cultural elite, Feyer found himself discussing media theory with McLuhan, boyishly flirting with Callwood, and carousing with Berton, all of whom were engrossed by Feyer’s ribald wit and iconoclastic attitudes towards politics, religion, and sex.

“He would ask girls to lend him their belly buttons, and he would draw — using their belly button as the focal point — all kinds of highly amusing and very clever cartoons,” Jonas recalls. “It became a bit of a distinction to have a Feyer cartoon tattooed on your belly.”

He drew faces on Berton’s bald pate, a leering man peeking out of the top of Callwood’s dress, and a trapeze artist swinging from a necklace just above his fiancée Fitzsimons’ looming cleavage.

During Feyer’s trips north to the Berton family home in Kleinburg, Ontario, Peter Berton — one of Pierre’s sons — remembers him drawing on everything, from walls and light switches to kids and animals.

“I remember he drew a lion tamer on my walls,” said Berton. Feyer also defaced a neighbour’s white Persian cat who was innocently relaxing in the Berton’s living room. When he was finished, “Fluffy” had a beret, moustache, bow tie, dinner jacket, and red-striped socks.

As his reputation spread, CBC took notice and recruited Feyer’s lightningfast skills for the then-infant medium of live television. In 1953 he made his TV debut on the children’s show Telestory Time, where he donned a corny beret and artist’s smock to illustrate a story read by cheery host Pat Patterson. His success on the biweekly show led to other gigs on kiddie shows like Razzle Dazzle and Pick-A-Letter, both of which ran in syndication well into the 1970s.

A segment from Razzle Dazzle provides a quintessential example of Feyer’s commanding talents. As Feyer stands by, a boy draws a loopy squiggle on a blank piece of paper. The cartoonist turns the paper on its end and in less than thirty seconds transforms the boy’s scribble into a defeated-looking barfly perched in front of a pint of beer. He adds a straw to the barfly’s glass and, taking it all in for a second, says to the boy, “Man drinking milkshake.”

It was ingenious and slightly subversive, not unlike his work during the war, and it helped vault him into the public eye.

“Feyer belongs to that generation of performing cartoonists like Al Capp and Ben Wicks,” said Jeet Heer, a cultural historian and writer about comics. “They were part of the entertainment industry.”

But while many fondly remember his work from this period, Feyer came to resent it. “I am not a funny little man,” he told Maclean’s in 1960. “I am sad and serious. I am so serious that when I am on TV they have to get a stagehand to poke me in the back with a broom to remind me when to smile.” According to his son, Tony Feyer, “He didn’t really like the kid’s stuff, but it paid the bills. He loathed doing it.”

In time he parlayed his talent into more adult fare, performing on The Joan Fairfax Show, The Midnight Club (hosted by Pierre Berton), and The Wayne and Shuster Show. In 1955, he began a high-profile gig on Hockey Night in Canada, drawing cartoons to go along with the post-game commentary. Later he landed a spot on The Steve Allen Show and was hired by marketing agencies to do commercials for Esso Oil and other clients.

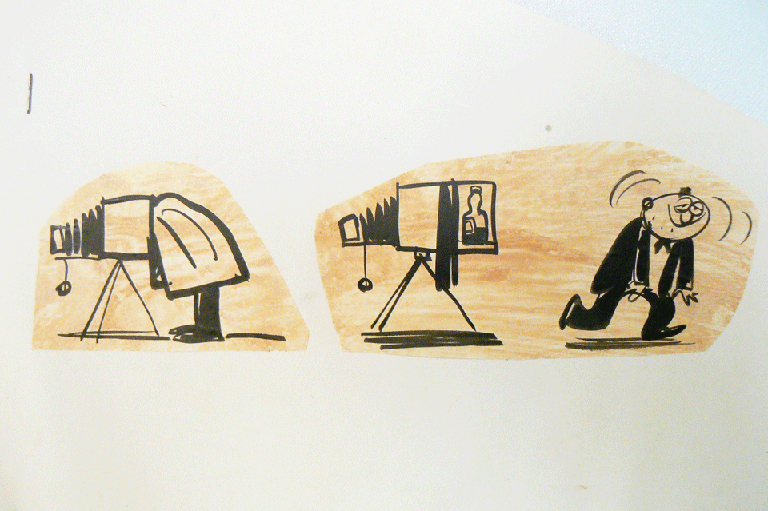

His act became so popular that he registered a patent for his innovative Mobiline process, which involved drawing on a special translucent paper, in reverse from behind. To TV viewers it gave the illusion that his cartoons were drawing themselves.

In 1955, bolstered by his newfound success, he convinced Fitzsimons’ parents to let the pair tie the knot, which they did on July 1 in a hotel in New York City. They moved into a house in Toronto’s Rosedale neighbourhood, which they promptly filled with antiques picked up during their summer holidays in Europe.

Over the years Feyer kept experimenting with new platforms for his panoramic talent. In February 1956 he branched out into fashion, collaborating with a Toronto designer on an outfit that featured his Mexican- themed drawings. In June 1959 he performed an illustrated history of the St. Lawrence Seaway on a twenty-three-metresquare projection screen on Toronto’s Front Street as part of the waterway’s opening ceremonies — Queen Elizabeth watched a live broadcast of this in Montreal. In 1963 he performed at a Liberal candidate debate; a year later he and his marker played the part of the Cheshire Cat in a “jazz-opera” version of Alice in Wonderland.

On May 30, 1959, his wife gave birth to their first and only child, Tony. A joyous Feyer told Maclean’s that he planned to “bring him up as a vulgar millionaire.” By the 1960s Feyer had become something unprecedented within Canada: a celebrity cartoonist, with fans who would frequently interrupt his walks with his dog, Molly, to offer him ideas for his next cartoon. A ropy-haired Hungarian puli, Molly became something of a child and confidant for Feyer during the last decade of his life. “He was so incredibly devoted to that dog,” Tony Feyer said. “I think he probably preferred the company of an animal to a human being at times.”

By the late 1950s, Feyer was growing weary of what he considered editorial interference with his work. He told Berton in 1959 that all of his favourite work was being rejected “in favour of cartoons which he drew under duress but hated for their banality.”

One of his 1952 cartoons depicts a man pitching a series of cartoons to an increasingly amused editor. In the final panel the editor stops laughing, hands the portfolio back to the cartoonist, and sends him on his way. The message couldn’t have been clearer: Feyer’s cartoons were insightful and hilarious — but the reserved readership simply wasn’t ready for them.

“Feyer had a sense of humour which a number of people found weird,” said Jonas. “I frankly didn’t; I found it a kind of central European gallows humour. He was an immensely talented guy, but he hated prudishness and small-mindedness. He helped loosen up the kind of uptightness that was characteristic of Toronto and Canada in the 1950s. That period was very uptight, and George was one of the people who helped liberate it. He produced the sixties more than the sixties produced him.”

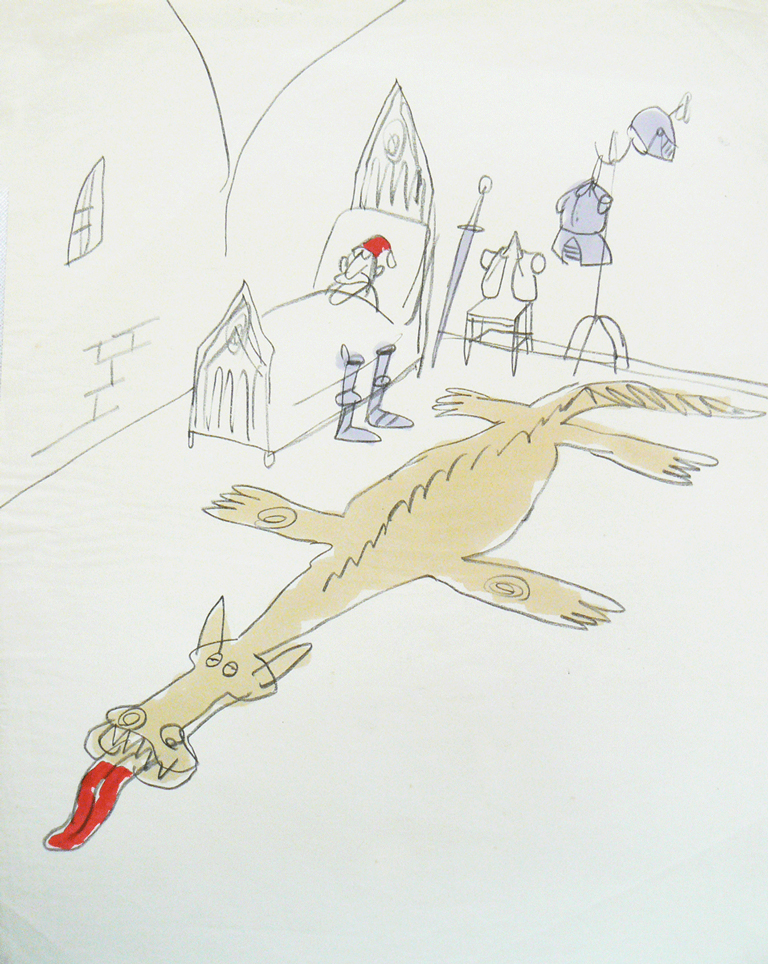

According to Mosher and Berton, more than half of Feyer’s best work never saw print. This included two proto-graphic novels: My Son the God, a wickedly funny take on the Second Coming, and another devoted to suicide, which is sadly lost to time.

Mosher sympathizes with Feyer’s frustrations with editors. “Listen, we’re dealing with people who haven’t got the vaguest ideas of what it is we do, or how we do it — they just know that it’s popular. And what really pisses them off is [that] we’re probably more popular than they are.”

By the early 1960s Feyer had reached a personal and professional turning point. Estranged from his wife (who was addicted to barbiturates and amphetamines) he was becoming increasingly disillusioned with his career in Canada. According to Berton, Feyer felt that he was being taken for granted in Canada, with many clients either stalling him on jobs or not paying at all.

One example of this was the TV show Pick-A-Letter, which saw Feyer draw stories based on a letter of the alphabet. Produced by Screen Gems between 1962 and 1963, the short segments were widely syndicated in Canada and the U.S. and proved so popular that they survived in reruns for nearly two decades. The show was clearly founded on Feyer’s singular talent and could not have existed without him, yet friends say the royalties he was promised were never paid out.

“George was a great talent who I don’t think ever got his due,” said Franklin, “and what bothered people so much was that he never made a penny from that show. Pick- A-Letter was so good, and he never made a penny for it.”

With his work either being exploited on TV or lobotomized in print, Feyer decided to take his substantial talents south to Los Angeles, joining an exodus of Canadian talent that had left the country in search of new work and fresh success. This brain drain included actor Lorne Greene, author Arthur Hailey, and director Norman Jewison, all of whom preceded Feyer and all of whom had been embraced by Hollywood. Feyer escaped to California in the summer of 1965 and rented an apartment in the sunny heart of Hollywood for Molly and himself.

The Globe and Mail caught up with him in September and depicted Feyer as an in-demand talent; he had taped a segment on The Danny Kaye Show alongside Clint Eastwood and Buddy Ebsen and had just booked $21,000 in commercial work. A few months later he was taping TV specials with comedian Mort Sahl and musician Roger Miller.

In a letter to his childhood friend Hansi Forgash dated December 29, 1965, Feyer sounds busy and optimistic, but isolated. “I’m terribly lonely here. I have the Carpenters [Edmund, a well-known anthropologist] and sometimes Barry [Morse] for friends. But mostly Molly.”

A year later, on December 17, 1966, Maclean’s ran a two-page feature on Feyer’s new life. “Like most Canadian brain drainers his feelings are mixed,” it noted. “His income has doubled, but he finds the city ‘superficial, heartless and insane.’”

Another letter written to Forgash a few weeks later shines a harsher, more honest light on his Hollywood existence: “Thanks for the news clippings. I hope you didn’t believe a word of it because all that horse shit was of course Hollywoodese propaganda for myself. The truth is between you and me that life is hard, although hopeful. I miss Tony and worry about Michaela. ... I can’t imagine what would happen to her and Tony if I would be hit by a truck or kicked by a canary (ouch!). It’s beautiful here if you deduct the people. They are full of horse shit up to their ears.” (The word “horse shit” was deployed using a rubber stamp he had devised, with the words appearing in large Gothic script.)

That was the last anybody heard from him. Less than three months later Feyer was found dead in his apartment of an apparently self-inflicted gunshot wound. Edmund Carpenter, who discovered his body on March 31, 1967, initially told the Toronto Star that his friend had killed himself several months after learning he had a brain tumour. Yet Feyer made no mention of the tumour in his letter to his old friend Forgash just a couple of months prior. Adding to the confusion, years later Carpenter took back this detail in a conversation with Tony Feyer, for whom he had become a stand-in father figure.

Feyer’s death devastated his friends and family. A wanlooking Lister Sinclair appeared on CBC-TV the following week to eulogize Feyer, his shaky voice devoid of its usual erudition.“George was a kind, sweet, depressed man most of his life [who] thought of life as a four-letter word,” Sinclair said.

Pierre Berton was “very hard hit” by his friend’s death, said Berton’s son. But he wasn’t particularly surprised, since Feyer had exhibited suicidal tendencies throughout his life.

In fact, Feyer’s work is littered with references to suicide. There were cartoons of men hanging themselves, cutting off their heads, overdosing on pills, and with guns pointed at their heads. In his first apartment in Toronto he drew a priest and mourners on the wall overlooking his bed, as if he was a coffined corpse while sleeping.

As the shock waves abated, the rumours began to circle — about money problems, mental illness, alcohol and substance abuse. Fifty years later, question marks continue to hover. Berton’s eulogy in the Star mentions Feyer’s Hollywood apartment being covered with his cartoons: “Drawings on the walls and the ceiling, drawings on the radiators and the bathroom tile, drawings on the very door handles, drawings stuffed into closets, piled against the bed, stacked in piles on the floor, unfinished on his desk and [drawing] board.” However, Tony Feyer, who spent a summer with his father in Los Angeles, disputes this account, insisting that Feyer always kept an immaculate studio.

In his public encomium in the Star Berton recalled that while visiting Hungary with Feyer in 1963, for a week-long series called “Berton Behind the Curtain,” Feyer “invariably asked gypsy musicians [whom he hated] to play ‘Gloomy Sunday,’” the very song he had mocked decades earlier.

Sinclair all but diagnosed his friend with post-traumatic stress disorder: “The war was very bitter to him. I remember he told me that he would wake at night dreaming of the piles of corpses.”

And, there was a previously unreported incident that occurred in January 1967, just three months before his death, as told by his son. “He went to this meeting in L.A., and he left his dog [Molly] in the car,” Tony recalls. “He was only supposed to be in the meeting for a brief period of time, so he parked the car in the shade with the window open a crack. But he got stuck in this meeting much longer than he anticipated, and the angle of the sun changed, and unfortunately it baked the car, and the dog ended up dying of hyperthermia in the car. It wasn’t long after that that he offed himself.”

In a letter Carpenter wrote to Berton dated April 11, 1967, the anthropologist added a further layer to the mystery: “When I first talked to you immediately following George’s death, I spoke of his depression, the inevitability of it all, etc. I later found out that this was only part of the picture. Toward the end he was fighting with everything in him, working furiously, developing new styles, moving into new fields, etc. The correspondence he left behind — carbons of letters to agencies — indicate that he was determined to make it no matter what the obstacles. Some of these letters were written the day of his death. And there was much else — recent dental bills, library books checked out, etc. — that suggest that both the life and death wishes were very strong toward the end.”

Of course, we can never be sure of the cause of Feyer’s tragic end. The Los Angeles coroner’s office didn’t conduct an autopsy, and by the time Michaela Feyer and their son Tony arrived in Hollywood his body had been cremated. Like every suicide, the question marks that are inevitably drawn can never be erased.

“It was the way he chose to go,” Berton wrote in a eulogy in the Toronto Star a week after Feyer’s death. “And we who were his friends, can have no quarrel with it. We can only mourn the waste.”

In the end, maybe the genius with the felt-tipped marker simply ran out of canvas.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk necktie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. Made exclusively for Canada's History.