Washday: The Weekly Ritual

Spend an hour watching any commercial television network and you’re sure to be bombarded with laundry advertisements. Detergents, bleaches, stain removers, fabric softeners, washing machines, and automatic dryers are just some of the products offered. Popular magazines also contain a large number of laundry-related ads, most directed at women, who shoulder much of the responsibility for the family wash.

Article continues below

-

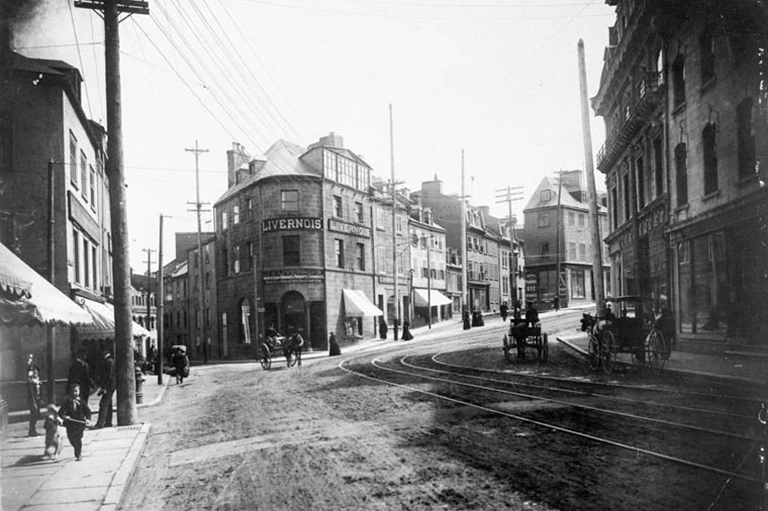

Sheep Creek Laundry and Bath in British Columbia's East Kootenays, circa 1900.B.C. Archives

Sheep Creek Laundry and Bath in British Columbia's East Kootenays, circa 1900.B.C. Archives -

It wasn't until the 1960s that the automatic dryer became common in Canadian households. Until then, most laundered clothes were hung and dried outdoors (in the summer).Library and Archives Canada / PA 133474

It wasn't until the 1960s that the automatic dryer became common in Canadian households. Until then, most laundered clothes were hung and dried outdoors (in the summer).Library and Archives Canada / PA 133474 -

Marie Leclerc washing clothes outside her Cantal, Saskatchewan house, with a washing machine operated with a small motor, circa 1921.Saskatchewan Archives Board / RA 20058

Marie Leclerc washing clothes outside her Cantal, Saskatchewan house, with a washing machine operated with a small motor, circa 1921.Saskatchewan Archives Board / RA 20058 -

The "dolly" or washboard make, which has two corrugated boards for rubbing the dirt out.Eaton's

The "dolly" or washboard make, which has two corrugated boards for rubbing the dirt out.Eaton's -

Margaret Hyde, domestic for the James Ballantyne family of Ottawa East, irons clothes in 1892.Library and Archives Canada / PA 131939

Margaret Hyde, domestic for the James Ballantyne family of Ottawa East, irons clothes in 1892.Library and Archives Canada / PA 131939 -

A Rinso ad from the February 1934 edition of Chatelaine. Like many advertisements for soap powder of the day, emphasis was on relief from the drudgery of laundering clothes. Whiteness and brightness were secondary concerns.Thomas Fisher rare book library, University of Toronto

A Rinso ad from the February 1934 edition of Chatelaine. Like many advertisements for soap powder of the day, emphasis was on relief from the drudgery of laundering clothes. Whiteness and brightness were secondary concerns.Thomas Fisher rare book library, University of Toronto -

1949 Procter & Gamble advertisement for laundry soap. Heavily advertised soap powders, which replaced cumbersome bars of laundry soap that had to be scraped and boiled before use, helped to create an enthusiasm for spotless cleaning.Procter & Gamble inc.

1949 Procter & Gamble advertisement for laundry soap. Heavily advertised soap powders, which replaced cumbersome bars of laundry soap that had to be scraped and boiled before use, helped to create an enthusiasm for spotless cleaning.Procter & Gamble inc.

Feminists have criticized the inane portrayal of women in advertisements, which would have us believe nothing matters more than clean, bright clothing. Probably few women would disagree with this perspective, at least not openly. But doing the laundry—and doing it well—has been an integral part of female culture for generations. It is also an aspect of women’s work that is particularly subject to public scrutiny. A woman can hide poor cooking or housekeeping skills from outsiders by not inviting guests to the house, but clothes are worn in public, where everyone can judge their cleanliness. And cleanliness is important, because cleanliness and respectability have been interconnected in our culture for several hundred years.

Laundering of clothing and household items probably began soon after woven cloth appeared, but the practice was limited to the wealthier classes. The absence of running water and the high cost of soap made it difficult for most people to wash regularly. As social historian Lawrence Stone notes, in the eighteenth century, “the poor were very much dirtier than the rich. Lower-middle and lower classes of the late eighteenth century changed bed sheets no more than three times yearly, and women wore quilted petticoats that they never washed, replacing them only when they had almost fallen apart.”

Standards of personal cleanliness changed in the nineteenth century when cash wages and cheap manufactured goods, including easy-to-care-for cotton clothing, became available. In addition, the cult of respectability took hold, with its notions of cleanliness and godliness. In established communities in both Europe and North America, high standards of cleanliness could be adopted readily by those who had the inclination and the means. But the situation in the pioneer homes of Upper Canada posed some problems. As Jane Errington points out in her study of working women in Upper Canada, early settlers often found it difficult to obtain new clothes or the fabrics with which to make them, so extra effort went into ensuring that garments lasted as long as possible. An essential part of this process was regular washing, which usually look place on Monday or Tuesday, sometimes weekly, sometimes less often.

Genteel pioneer women had to compromise between the expectations that prevailed at home and the realities of frontier life. In the earlier part of the nineteenth century, the frequency with which a wash was done was directly related to social status. Upper-class households could afford larger wardrobes, and so washed every four months, or in some eases, even once a year. To wash clothes more frequently than every six weeks suggested poverty. At the same time, well-to-do nineteenth-century women wore their dresses several times before laundering them, since their outer clothing did not come into direct contact with the body. They were, however, encouraged to change their undergarments frequently, with some ladies’ magazines suggesting fresh linen every time a woman changed dresses throughout the day.

Before washing could begin, extensive preparations had to be made. In pioneer communities, women usually made their own lye and soap, even when commercial products were available. Partly this was due to lack of ready cash, but it was also a matter of personal pride. Lye, a strong alkali concocted from wood ash and bones, was difficult to produce. As late as 1848 American household manual author Catharine E. Beecher included instructions for preparing and testing lye. A hatch of lye that was too strong could be diluted with water, she reported, but the only remedy for lye that was too weak was to start over. Soap, made from lye and animal fat, could be difficult to produce, too. In The Backwoods of Canada, Catharine Parr Traill talks about the mystery of the process, noting that even experienced servants weren’t sure why some batches turned out and others did not.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Laundry equipment was rudimentary. In Country Life in Canada, Caniff Haight remarked, “The only washing machines were the ordinary wash tubs ... and the brawny arms and hands of the girls; and the only wringers were the strong wrists and firm grip that could give a vigorous twist to what passed through their hands.” Mrs. Beecher’s 1848 list of equipment included four tubs of different sizes, a large wooden dipper, two or three pails, a washboard, clothesline, a stick for moving clothes when boiling, a fork to take them out, and a copper kettle. Most pioneer households probably had fewer tubs and pails, an iron kettle (which rusted more quickly than copper and so was more likely to stain clothing), plus a washboard, and possibly a dolly-stick or pounder—an instrument resembling a three-legged wooden stool with a handle attached that was used to force water through clothing.

Hauling water for the wash was one of the most onerous steps involved, which was why women hired help specifically for washdays. Some domestic servants bandied a range of chores, but a number specialized as washer women. Writing in 1837, William Mills of Port Maitland, at the mouth of Ontario’s Grand River, noted that Dederika Memlingh Johnson, wife of a retired Last India Company engineer, hired a woman to help with the wash. “Washing is the most lucrative trade possible here,” Mills reported. The laundress, who worked for other women as well as Mrs. Johnson, earned about $20 a month. Nearly forty years later, teenage diarist Hattie Bowlby of Port Dover reported that her mother sometimes brought in a Mrs. Stoneman to help with the wash.

The actual process of washing involved three steps—soaking, scrubbing, and boiling. Soaking might start two or three days before washday, although this created problems in warm weather when the water quickly went stagnant. Stains might be treated just before or after this stage, using compounds that included everything from vinegar, onions, and buttermilk to chemicals like oxalic acid. Usually, though, the tried-and-true method was to scrub with a brush or on a washboard. Even this seemingly simple task required a certain skill, as Susanna Moodie discovered when her servant was away visiting family and she decided to tackle some “small baby articles“ herself.

“After making a great preparation, I determined to try my unskilled band upon the operation. The fact is, I knew nothing about the task I had imposed upon myself, and in a few minutes rubbed the skin off my wrists, without getting the clothes clean.”

Once the scrubbing was complete, it was time to boil the laundry. Here, again, knowledge and skill were essential if clothing was to be kept in good condition. Wool could not be boiled, and might turn into a hard, felt like fabric if not washed rapidly in cool water. Most clothes were not colour-fast and had to be sorted and washed separately. Buckskin items, which formed part of some early settlers’ wardrobes, posed other problems, as Polly (or Poll) Sprague of Port Ryerse, Ontario, found out in the early 1800s. One day Polly was left alone in the family cabin with instructions from her mother to wash her only garment, a buckskin shift. Polly recalled seeing her mother boil her father’s and brother’s shirts in a strong lye solution, and according to neighbour Amelia Harris Byerses account. Polly “subjected her leather slip to the same process. ... When Poll took her slip from the pot it was a shrivelled-up mass, partly decomposed by the strong ley [sic].” With no change of clothing, Polly was forced to hide in the potato hole under the cabin floor until her mother returned and gave her one of her own woollen slips.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Clothing that could be boiled was usually kept in water for about an hour, stirred with a long stick, removed with a fork, rinsed, and hung to dry. Pioneer housewives used bushes, fences, and other handy locations, a practice that was still common among European agricultural communities in the mid-nineteenth century. Some had clotheslines, which usually had to be held up by a forked stick at various points in order to keep laundry from trailing on the ground. Drying clothing outdoors had advantages— both sun and frost helped to whiten items—but it also meant that laundry might take several days to dry in wet weather. There were also occasional hazards, including local wildlife. In Sketches of Upper Canada, published in 1821, John Howison recounts the story of a woman who sent her daughter to hang clothes on some nearby bushes. When she stayed away too long, her mother investigated and found her “pale, motionless. ... The sweat rolled down her brow, and her hands ... clenched convulsively.” Her gaze was fixed on a nearby log, where a large rattlesnake was swaying menacingly. The mother was able to drive the reptile away with a stick, but doing the wash was probably an anxiety-inducing experience for the girl for a long time afterward.

Snakes and bad weather may have made drying clothes indoors seem attractive, but few cabins were large enough to comfortably accommodate a family’s wash along with all the other household activities.

Labour Saving Machines?

During the First World War, farmers were called on to increase production to help the war effort. Their wives were also expected to pitch in, but found themselves wondering how to do this and still handle household chores.

In March 1918 one possible solution was proposed by Katherine Kent in the women’s page of the Toronto Globe. Washing machines, she suggested, could free women for other chores, or even for taking life a little easier. Her article described the main types of machines available:

The “dolly,” or washboard make, which has two corrugated boards for rubbing the dirt out; the “revolving cylinder” make, which is not unlike the peanut roaster plan, an inner cage holding the clothes and revolving them through the soap and water in the outer cylinder, so many times one way, so many times the other. The “pressing” and “suction” washer has cones which come down and press the clothes, and on being lifted cause a suction which draws the dirt. The “oscillating” kind throws the clothes with the suds in a sort of cradle, and does its work by rapid agitation.

With any of these machines—and a wringer—Kent promised “you can do a large washing without being tired out especially if there was running water and a handy drain. About all you have to do is the planning.”

Of course, women also needed to add soap—one pound soap chips and one cup ammonia to five gallons of hot water. To those who still preferred to boil their clothes, Kent suggested pouring boiling water over the suds as a time-saving measure. Then it was simply a matter of wringing the clothes out, rinsing again, adding bluing, and when the wash was done making sure the washing machine was clean and well-oiled.

Domestic Life

Margaret Hyde (below), domestic for the James Ballantyne family of Ottawa East, irons clothes in 1892. Before industrialization, washerwomen may have enjoyed a higher status than many domestic servants or farm labourers. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, women in Aix-en-Provence were earning twelve sous a day for laundering, compared to eight sous a day for field work. In the 1830s, William Mills of Port Maitland reported that Upper Canadian washerwomen were well paid. Thirty years later in his native Britain, washerwomen were paid two shillings per day, plus food and beer (more if meals were not provided), and they only handled the actual washing. Preparation, assembly of equipment, wringing, ironing, and other tasks were the work of other servants or the women of the households.

There is considerable evidence that at certain times and in certain places washerwomen could set the conditions of their employment, move freely from household to household, and earn more than other domestics. However, studies of British and French washerwomen in the late nineteenth century reveal they worked long hours for little pay in terrible conditions, especially in commercial laundries. The downward slide in their working conditions seems to be directly related to industrialization.

Besides, during much of the pioneer era, washing was a primarily outdoor activity, and quite messy in the bargain. Feet and clothing got very wet, making washday sheer misery in the colder weather. Although British women may have imported the practice of wearing heavy aprons and patens (metal rings that elevated shoes off the ground), they still had to contend with the heal and humidity, the constant exposure to hot water, soap, and other laundry aids that ruined hands, and the lifting involved in filling, emptying, and refilling tubs. One study showed that 75 per cent of late nineteenth-century French laundresses suffered hernias, and many housewives probably suffered similar injuries. They weren’t the only family members at risk: The fire, scalding hot water, and caustic cleaners necessary to a nineteenth-century wash were dangerous to young children, who were invariably underfoot.

As the Upper Canadian frontier disappeared, settlements grew larger and various luxuries became increasingly available. But laundry continued to be done in much the same way as it had in the pioneer era. Margaret Ann (Stewart) Ritter recalled as a child helping her grandmother with the laundry in Dunnville around 1920. Although the household had running water, washing was still a chore. A heavy copper laundry tub was placed across two burners on the gas stove, and then pails of water were poured in. Soap powder was added, the gas jets were turned on, and the mixture was brought to a boil. Then the clothes were added and stirred with a big wooden stick for about an hour. Once the clothes were clean, they were put into a wash pan and the hot water was ladled out of the laundry tub until it was light enough to be lifted and emptied. It was then filled again in order to rinse the clothes. After this was done, the tub had to be emptied once more. Though Margaret remembered her grandmother wringing the clothes by hand, most households by this time had a mangle, or wringer, which could be attached to a tub and reduced the effort involved in wringing clothes.

Many attempts were made to develop washing machines throughout the nineteenth century. Between 1804 and 1873, 1,667 patents were issued in the United States for washing machines. Canadian patents were not issued until 1824. but the very first was for a “Washing and Fulling Machine.” Over the next forty-five years, sixty-three Canadian patents were granted for improvements in washing machines. Most developments were designed to make repetitive tasks somewhat easier. One early washing machine simply borrowed the idea of the washboard, made it cylindrical, and attached a crank to turn it. An early wringing device involved a bag into which clothes were placed. The bag was clamped at either end and one of the clamps twisted by a handle, forcing water out of the clothes in the process. Most of the early designs were rejected because they damaged clothes or were so cumbersome to operate that even servants refused to use them.

When washing machines existed, however, there was no guarantee they would get into the hands of the women who needed them. Much To Be Done, Frances Hoffman and Ryan Taylor’s examination of domestic chores in Victorian Ontario, includes the recollections of Mary Hutchinson Orr of Nichol Township, Wellington County:

The first we ever heard of was through an agent who called, He met father at the gate and asked if he could sell him a machine. Father said he had two very good ones in the house, He wanted to know what wake they were and father said he had better come in and see. So he brought him in to where sister Sara and I were busy with tubs and boards.

William Hutchinson probably had little concept of how burdensome the family wash could be. While the responsibility might have been appealing when young women first took on the task, the novelty soon wore off. Matilda Bowers Eby of Berlin (later Kitchener), Ontario, whose diary is also excerpted in Much to Be Done, wrote in January 1863, “I always like to wash“ and in May 1863, “it always makes me feel well and active when I take wash-tub exercise.“ But by September 12, 1865 she was thoroughly tired of doing laundry. “Am extremely tired tonight. ... The poor wretched women have the same course of work to pass through week, after week, no wonder if they would get tired of it.” In some households, washdays upset the normal routine, taking up so much time and energy that it was nearly impossible to serve regular meals, even with live-in domestic help.

Yet there were also enjoyable aspects of washing. Ruth Rushton, horn in 1908 and raised on a farm on the north shore of Lake Erie, fondly recalled laughing with her mother “in the airy woodshed in summer.” Sometimes, washing could he a community social event. In 1927, Mary E. Wilson wrote an account of washday around 1852 at Mount Olivet, near Cayuga, Ontario, when several women gathered around a pond in the woods to do the family washing:

There would he the Lanes, Smiths, and the different Wilson families, and they had a big black iron pot hung up, in which to heal the water which was soft... Ellen Smith ... had a white muslin dress with blue flowers in it, that she used to wash there ... the girls always had quite a sociable time while the clothes were lining, although the Wilson girls usually took theirs home in a basket on a wheel barrow and hung them on a line to dry.

A household supply of water and other amenities soon put an end to communal washdays. By the time Margaret Ritter and Ruth Rushton were helping with the family wash, women were demanding and getting better laundry equipment. Some took advantage of the new commercial laundries that were accessible in even the smallest towns. Port Dover, for example, with a population of less than 1,200 in 1900 had an agent for the Parisian Steam Laundry in Brantford, eighty kilometres north. Clothing was sent to Brantford by train. And in Western Canada especially, laundries operated by former Chinese railways workers further commercialized the practice.

By the end of the First World War, modern equipment was helping to relieve some of the burden, but washday still required stamina and energy. Until the mid-1950s, when automatic washers became common, electric-powered washing machines had to be filled and drained by attaching hoses. Wringing involved lifting each item out of the tub and running it through motorized wringers. Many housewives continued to wash finer items by hand and hang laundry on clotheslines until the 1960s.

Today’s women no longer have to worry about getting the right strength of lye, or hauling water as their grandmothers and great-grandmothers did. But those ubiquitous commercials make it clear that laundry is, as it always has been, an integral part of women’s lives.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!