Think on Me

One evening in February 1968, singer Judith Lander was sitting in her small apartment in Toronto. She was in her early twenties and had recently moved there from Winnipeg. With a few television gigs on her resumé, her career in popular music was taking shape. The telephone rang. It was her teacher, the famous Canadian contralto Portia White. Her voice was unusually husky, not the soft, honeyed voice Lander was used to. A caring and attentive teacher, White asked her how she was. She was sorry that Lander would not be pursuing a career in opera, but she was certain that, whatever Lander decided to do, she would be successful. White said that although she would no longer be teaching her, she had one request: “Judy, please take your vitamins.” As they said goodbye, Lander told her she would see her soon.

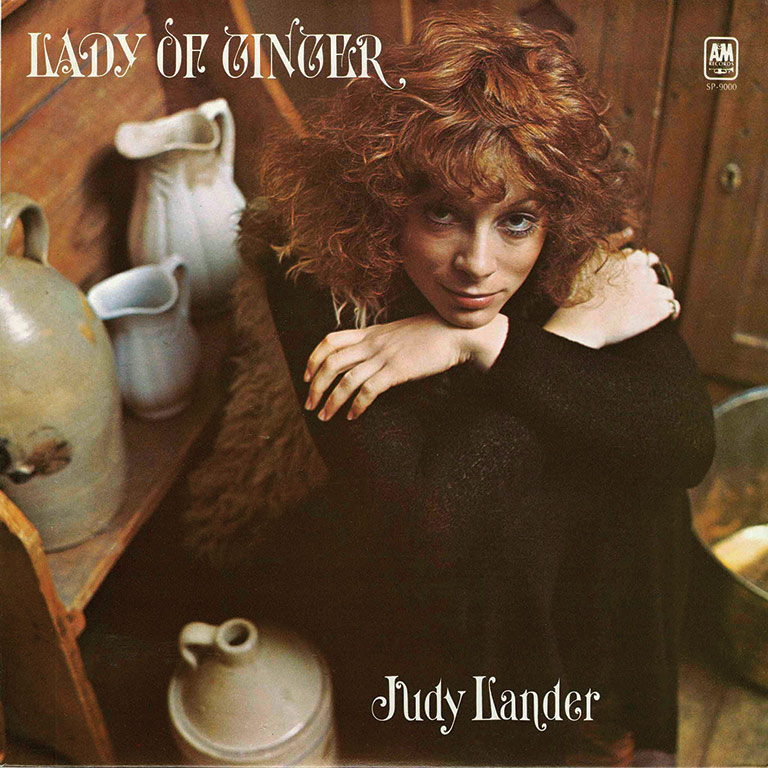

It was not to be. A few days after that memorable telephone call, Lander learned that White was quite ill. Unsettled by the news, she sat at her small piano as some lyrics came to her, and she composed a pleasing melody to accompany them. “Lady of Ginger,” a song for Portia White, was born.

The Lady of Ginger and velvet and honey and light

Breathed a child’s awe into me

The lady of ginger and velvet and honey and light

wore the cloak of dignity….

A raindrop fell on her nest of earth

and nurtured her sparrow song of purity

She rode on the wings of a nightingale

And her colour was liberty

The next morning, Lander heard on a radio newscast that White had died in a Toronto hospital at the age of fifty-seven. Those were troubled times. White’s death occurred barely two months before Nobel Peace Prize winner Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968. As for me, I was a teenager in Beechville, a Black community near Halifax, counting the months to June, when I expected to graduate, and at the same time wondering if I would be accepted into university. After all, when I entered high school, my grade nine teacher advised me to take the general program: “If you make it through,” she told me, “you might get a little job for yourself.”

Such were the low-level expectations and unjustified racist attitudes — whether intentional or not — faced by so many Black students of my generation and of the generations before mine, including Portia White’s. She earned accolades in the 1940s, a time when race, gender, and class determined what people could do and were expected to do, and in a province and country marked by a legacy of slavery and racial discrimination. But she was a dreamer, she was brave. How audacious of this Black woman to aspire to perform on the concert stage. It wasn’t done — that is, until Portia White. She was christened by a journalist as “the New Canadian Star of the Concert Stage. “ Hers is a remarkable story, but one tinged with more than a touch of sadness.

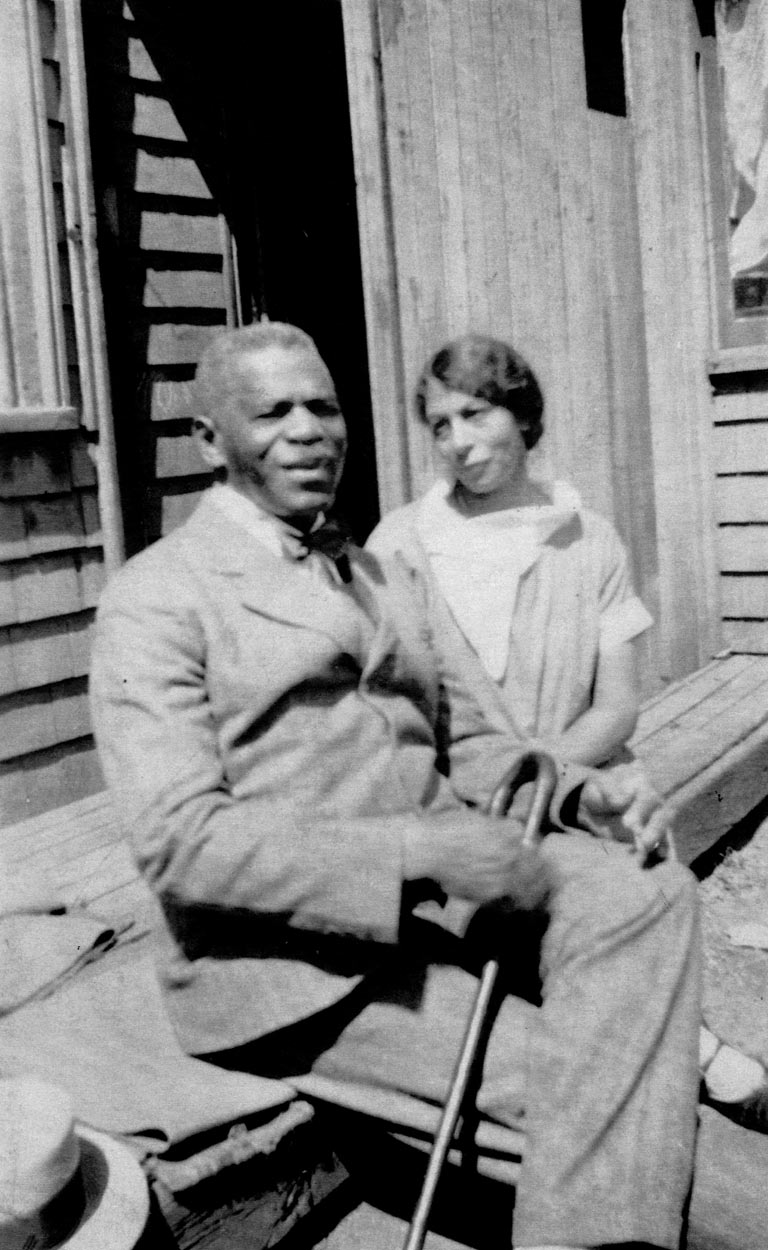

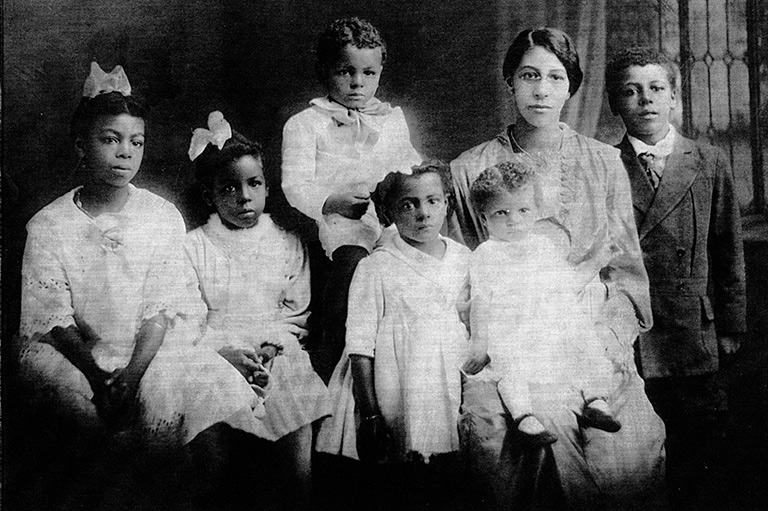

Named after Portia, the heroine of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, White was born in Truro, Nova Scotia, on Saturday, June 24, 1911. An adage says, “a Saturday child works hard for a living.” White did not disappoint. An early reader, she learned to play the piano when she was five years old. Along with her twelve siblings, she was raised in Halifax by her Virginia-born father, Rev. William Andrew White, and her mother, Izzie White, of Mill Village, Nova Scotia.

At the outbreak of the First World War, large numbers of Black men went to recruiting stations across Canada to volunteer but were turned away; they were told it was a “white man’s war.” After protests by Black leaders, including William White, and a debate in the House of Commons, the No. 2 Construction Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, a segregated, non-combatant unit of Black soldiers, was mustered on July 5, 1916, in Pictou, Nova Scotia. William White, named chaplain, was assigned the rank of honorary captain, becoming one of a very few Black commissioned officers in the Canadian contingent. He departed for France in 1917, leaving his wife to care for their six children, the oldest of whom, Helena, was nine.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

At war’s end William White was called to Cornwallis Street Baptist Church in Halifax. (Founded in 1832, it was renamed New Horizons Baptist Church in 2018.) As the family grew in the 1920s, Helena and Portia, the next eldest, helped to manage the household by taking care of the younger children.5

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Yvonne, the youngest of the thirteen, remembered Portia as a strong disciplinarian. Each morning, eight-year-old Yvonne sat while Portia braided her hair. Once at school, she and her friends would undo her braids, intending to redo them before she went home. One day she forgot. She faced the consequences: Portia spanked her, which was not an unusual action for the times but a shock to Yvonne. Her hair stayed braided ever after. Portia was not above pulling pranks, Yvonne explained. With sister Nettie she generously spiked their mother’s fruitcake with rum. Mother Izzie, who would never use liquor in her cakes, was none the wiser.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the sound of music wafted from their home on Belle Aire Terrace in North End Halifax. Passersby might hear the weekly choir practice, children’s piano lessons, brother Billy’s quartet singing a spiritual, or “Portia’s big voice rehearsing,” as her brother Lorne recalled. Izzie, an accomplished singer and mandolin player, gave her children an early start with regular singing and piano lessons, inspiring in them a lifelong love for music.

At the age of eight, Portia sang solos in the church choir and at the Halifax Music Festival. When she was old enough, she became the choir director. Family friend and choir member Aleta Williams said she was a meticulous director who taught everyone to perform well and to achieve the precise notes she expected. “Nobody ever told me to sing. I was born singing,” Portia told a radio interviewer. “I think that if nobody had ever talked to me, I wouldn’t be able to communicate in any other way but by singing. I was always bowing in my dreams, and singing before people, and parading across the stage as a very little girl.”

When she finished high school in 1929, her class prophesy predicted that within ten years she’d see her name in lights outside a concert stage. In reality, teaching was one of the few professional jobs open to Black women. After training, White taught in Black segregated primary schools — the only ones whose doors were open to her — in Black communities near Halifax. Her pay: thirty to thirty-five dollars a month.

These were the dirty thirties; times were hard. Death was a frequent visitor to the White family. Three young siblings died between 1921 and 1939. After William White died in 1936, money was scarce. Izzie White took in boarders to help ends meet, and Portia helped out financially whenever she could.

Music clung to her heart. She set aside $3.50 a month to pay for lessons at the Halifax Conservatory of Music. She entered the Nova Scotia Music Festival and won the competition for mezzo-soprano in 1935, 1937, and 1938. After winning three times, according to the rules, the Helen Campbell Kennedy Silver Cup was hers to keep.

The tumult of the Second World War brought a person into White’s circle who would change the course of her life: the singer and medical doctor Ernesto Vinci. Born Ernst Wreszynski to a Jewish family in Prussia in 1898, Vinci immigrated to Canada in 1939. The famous conductor Arturo Toscanini recommended that the Halifax Conservatory of Music should hire Vinci to head the voice department. The conservatory did so, and Vinci became White’s voice teacher and one of the architects of her career. The Halifax Ladies Musical Club, eager to help, paid for lessons for White, who by this time was already twenty-eight years old. Vinci saw tremendous potential in White’s gifts; he directed her voice change from mezzo-soprano to the rarer contralto range.

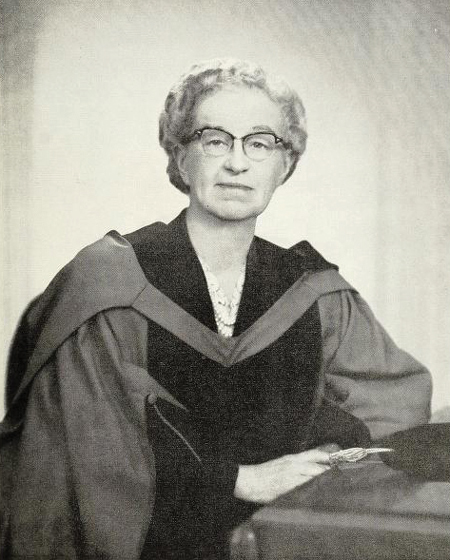

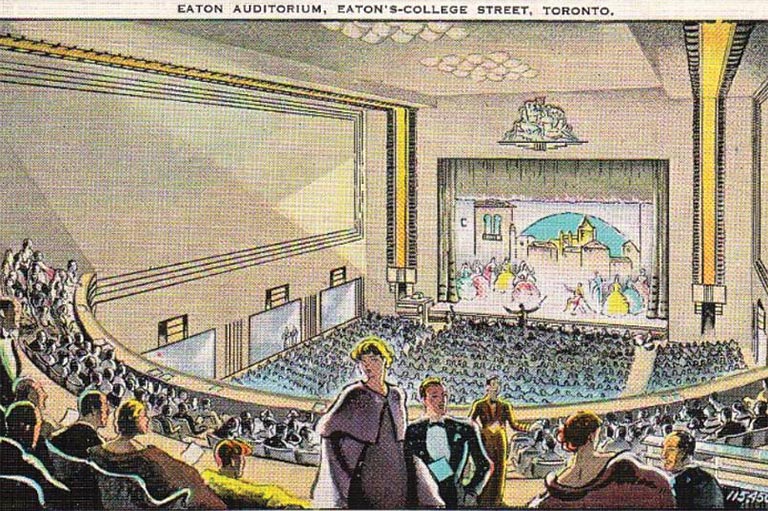

A fairy-godmother figure entered White’s story when Edith Read, the principal of the Toronto private girls school Branksome Hall, came home to Halifax for a visit. After hearing about White, she telephoned and invited her to sing for her. Afterwards, she was convinced that White should be heard beyond small Maritime venues. Using her connections, she arranged a debut at Toronto’s Eaton Auditorium, Canada’s leading concert venue. White later told a radio interviewer: “I must admit that I doubt very much that any other singer has ever ventured to do such a big thing after having done only two or three recitals.”

On the evening of Friday, November 7, 1941, accompanied on piano by fellow Haligonian Elaine Burns, the thirty-year-old White began her concert with Beethoven’s “Creation Hymn,” continued with selections by classical composers Elgar, Schubert, and Verdi, and closed with spirituals including “Li’l David Play on Your Harp.”

In glowing reviews, critics vied for superlatives to describe White’s talent and the elegance of her stage performance. Hector Charlesworth, reporting for Saturday Night, wrote, “When one considers that Miss White was singing for the first time in a large musical centre, before an audience of strangers, her poise was amazing. This recital indeed may well have been a milepost in a great career. Her tonal volume is remarkable, and she makes a beautiful use of it.” Her unusual voice range of three octaves — from a high A-flat down to a low D — turned heads, and she sang in several languages. Portia’s concert was a flickering light in a gloomy world racked by the Second World War.

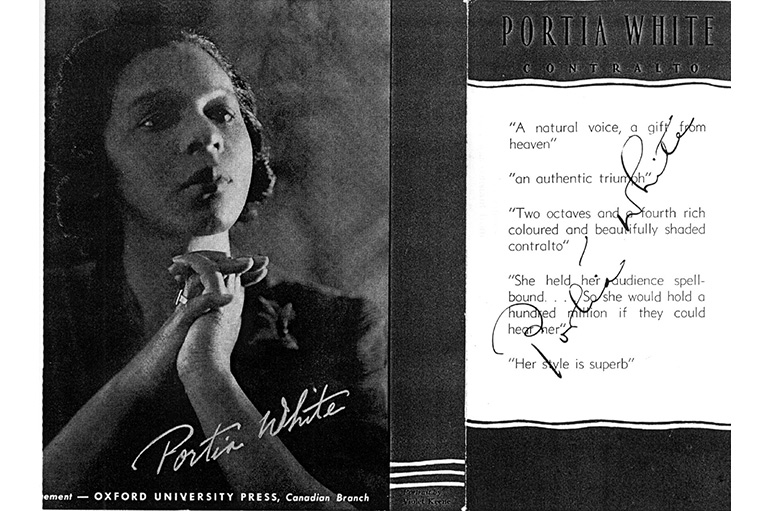

After White’s success, the Canadian branch of Oxford University Press (OUP) seized an opportunity: Its new concert management division in Toronto needed artists, and White signed on as one of its first. She wired the Halifax School Board to resign form her teaching position. White’s backers, thrilled with the prospects for her career, wondered if she could be as big as the famous American singer Marian Anderson, considered by many to be the finest contralto in the world. This comparison trailed White throughout her career.

Though its concert management division was created with good intentions, OUP’s inexperience in artist management would be exposed only two years later, in 1943, when confusion arose over White’s schedules, performance fees, and expenses. She made efforts to sort out the problems but to no avail. “They have deliberately made it impossible for me to see them,” she confided in a letter to Vinci that William Clarke, the head of OUP’s Canadian division, had “left for the West so that I shan’t see him now.”

While White’s musical intelligence and poise endeared her to critics and audiences, press reports often pointed out her race. “Portia White, Negro contralto of Canadian origin,” opened one New York newspaper report. In Saturday Night, she was “deep voiced, dusky skinned,” and “the young Canadian Negro girl.” Perhaps at play was an underlying assumption that such talent was exceptional or unusual because she was a Black performer singing the classical repertoire.

Therein lies the racial conundrum: People packed halls to see her, yet she still faced the colour barrier. Historian Hilary Russell, in an unpublished paper for the Historical Services Branch of Parks Canada, wrote that White was once given a room at a Canadian hotel but told she could not eat in the dining room. She was not welcome at Toronto’s prestigious Granite Club, which also rejected Marian Anderson because of her race. En route home from her triumphant 1946 South American and Caribbean tour, in spite of reservations made in advance, there was no room for her at a Miami hotel even though there was a room for her accompanist, Gordon Kushner. He said Portia handled the ordeal with dignity. He refused his room in protest. They stayed up overnight in the airport, waiting for a flight the next day. Portia White lived the truth of American scholar and activist W.E.B. Du Bois’s perceptive words: “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the colour line — the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea.” Racial events in 2020, well into the twenty-first century, cast in bold relief the frightening relevance of his assessment.

In 1943 audiences flocked to see White during her Canadian tour that finished in November with an encore at the Eaton Auditorium. That year she experienced the first of her health problems: She had throat surgery, a fearsome experience for any singer. Now under contract with OUP, she continued performing after a short rest — otherwise, she would have had no income. New York beckoned. White’s patron Edith Read knew stars were made there, and she knew who could pave the way. Her friend Edward Johnson, born in Guelph, Ontario, was the general manager of New York’s Metropolitan Opera. Read arranged for White’s audition. While Johnson liked what he heard, he told White that she needed more concert experience: Go home, perform more, continue training with Vinci.

During January and February of 1944, White practised her repertoire and performed concerts — dress rehearsals for her New York debut. She was drawn to songs that perfectly blended poetry with music and to spirituals. Audiences enjoyed these “sorrow songs” that became a signature part of her program; her accompanist Kushner said she relaxed more when performing them.

Read rented New York’s prestigious and trail-blazing Town Hall theatre for the evening of March 13, 1944. New York’s music circles were buzzing. When White graced the stage before an enthusiastic, racially mixed audience of a thousand, including a sprinkling of Canadians, she became the first Canadian woman to perform there. “An Unheralded Star is Born,” read the headline in New York’s P.M. Daily, whose critic Henry Simon reported, “she has one of the finest contralto voices to reach New York since Marian Anderson, with whom comparisons are inevitable.… She has enormous power.” Fame arrived at Portia’s door, “and from that time on,” she told a radio interviewer, “things just gathered impetus, and I was swept away on this tide of great activity.”

In May 1944 the government of Nova Scotia and the City of Halifax took an unprecedented step: They created the Portia White Trust, a special fund to support the career of their newly minted singing sensation. Regular allocations covered many, but not all, of her expenses. Officials gave White a white fox cape that she draped over her shoulders at later concerts. Agents from Columbia Concerts Inc. successfully courted her. She left OUP to sign a three-year contract with Columbia, one of the two largest artist-management companies in North America. Soon after, she moved to New York.

Columbia also required her to sign a separate one-year contract with a New York-based public relations company. She paid the company’s fee and her publicity expenses directly from her earnings. The cost of any voice coaching, essential to improving her performance skills, also came out of her income.

Between April and June of 1944, White performed in five concerts, the largest of which was the United Nations Victory Rally at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto. In July she travelled to several major U.S. cities as a star performer with the Fifth Annual Negro Music Festival, appearing beside luminaries such as composer W.C. Handy and poet Langston Hughes.

Town Hall’s music lovers cheered White’s encore performance in October 1944. Again, reviews were glowing, though at least one pointed to an unevenness in her voice. White knew her weaknesses and how much she still had to learn; her concentrated musical training had been cut short after her Eaton Auditorium debut. “Even now when I get a chance to be in Halifax I study with my teacher — one acquires many bad habits when touring,” she told a reporter. As the number of her concerts increased, visits home became infrequent. In 1946, accompanied by Kushner, she thrilled audiences during a three-month whirlwind tour of the Caribbean and South America. A highlight came in the Panama Concert Hall when a group of Black youth presented her with a special medal they struck in her honour.

White garnered a lot of ink. Lengthy profiles appeared in Chatelaine, Saturday Night, and Ebony. Readers learned that she liked to play tennis, tackle crosswords, embroider handkerchiefs, and read Christopher Marlowe’s plays. And she loved to cook, especially salmon from Nova Scotia that she sometimes had shipped to Toronto, where she stayed before and after her residency in New York. To account for her late start on the American music scene, White’s publicity material fudged her birth date, presenting her as eight years younger than she was. She attracted interest from other artists, too: Yousuf Karsh photographed her; Harold Pfeiffer sculpted her likeness in bronze; and her portrait, painted by Hedley Rainnie, now hangs in Nova Scotia’s Government House.

Today performers of White’s stature have assistants to take care of the myriad details of touring and performing. White seemed to have no one. Columbia agents in New York and Toronto controlled everything, from where and what she sang to her fees; they even commented on her hairstyle. Yet it appears that the level of support she needed to fulfill their expectations was not there. Often White took care of her own travel arrangements; she paid for and cared for her gowns and covered her accompanist’s fees and travel expenses. She was expected to gather reviews about her concerts to send to Columbia. “Have not succeeded in my attempts at collecting the write-ups,” she wrote to Vinci in July 1944, while on the road with the Negro Music Festival. “We have all been moving too quickly. I have not even seen them.”

By 1947, her Columbia managers began to falter. Tours and concerts were booked, then cancelled. “It is difficult to understand,” she wrote to Read, “why given so much time and my reputation, they have failed to make more definite arrangements.”

At home a family member was ill and her youngest brother was beginning college. She wanted to help. With few concerts, there was little income, and at the age of thirty-six her own health was failing. She had suffered a bout of pleurisy, a lung inflammation, from which she had recovered. Now, unbeknownst to most people other than close family members, she had breast cancer. It was the moment to move home — this time to Toronto, the city where she was first introduced to the music world beyond Halifax. Read offered White a temporary place to live at Branksome Hall along with a job teaching music to Branksome’s girls.

The move allowed White to spend time with her brothers Bill and Jack and their families, who now lived in Toronto. “Portia would play Schubert on the piano, and that was lovely,” her sister-in-law Vivian recalled. “She was quite interested in our life and how the children were doing and played bridge with them, scowling at her cards if they weren’t to her liking.” Family was important to White. “Portia made sure that she kept in touch with all the family members.… She would phone me on Fridays and tell me about what was happening with the other members of the family,” Jack White said.

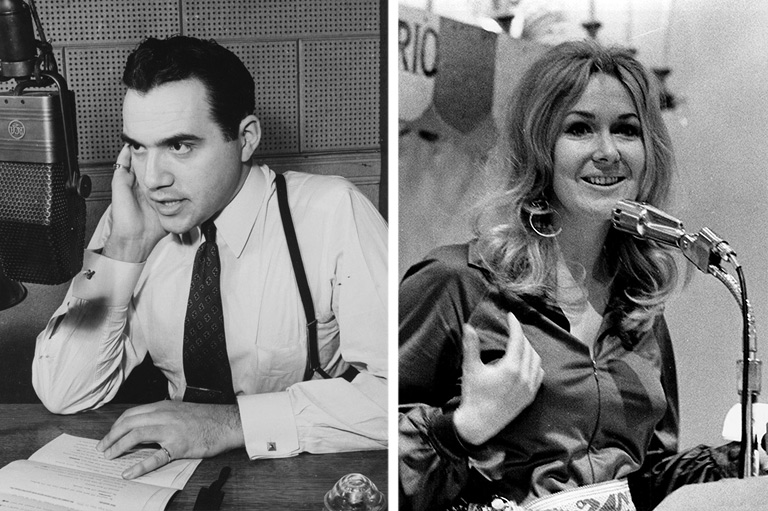

In the 1950s, Portia White established a teaching studio that attracted a who’s who of Toronto’s music, theatre, and television personalities. She taught actors Lorne Greene and Don Francks and singers Dinah Christie, Ann-Marie Moss, and Robert Goulet — names many Canadians knew from their appearances on early CBC television shows. Reflecting on her gift for teaching, she told a radio host in 1964, “I have found that I have a peculiar gift that I didn’t realize that I had…. A peculiar kind of articulate thing comes when I’m communicating with my pupils that is quite strange. Some of them tell me that I hypnotize them.” A few of those students, with no place to go, spent Christmas with her and her brother Bill’s family.

"The secret of singing,” White told writer Frank Morriss, “is in not stopping. Once you do it’s hard to come back.” But she did make efforts to do so in the 1950s and 1960s. She found a new teacher with whom to continue her studies and gave occasional performances. Ron Collier, who was soon to become a jazz legend in Toronto, organized a memorable concert with her at Casa Loma, a gothic-revival mansion in the city's downtown, in November 1958. “We are featuring Miss Portia White, who is going to be singing spirituals and folk songs accompanied by our guitarist Ed Bickert,” Collier told radio interviewer Leslie Bell, who found the pairing curious until White added: “We’re tracing the relationship between jazz as it is known today and the spirituals from which jazz has evolved.”

When Queen Elizabeth II officially opened the Confederation Centre in Charlottetown in 1964, White was among the artists invited to perform. She sang “Bonnie George Campbell,” one of the Queen’s favourites. “Her Majesty was interested in where I had travelled in my concert career and asked about the selections I sang,” she told reporter Dulcie Conrad. Her last public performance went back to her Baptist roots. She sang during the triennial assembly of the Baptist Federation of Canada, held at Ottawa’s First Baptist Church in 1967. By that year Portia had performed in nearly 150 recitals and concerts, but Columbia had never arranged any commercial recordings. The only ones extant were made backstage and were never intended for public release. Digitized by the National Archives in Ottawa, they were released by her family on CD in the early 2000s.

Nonetheless, her legacy stands. In 1999 Canada Post featured her image on a stamp in its Millennium Collection’s Extraordinary Entertainers series. She was named a Person of National Historic Significance in 1995 by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, and Nova Scotia established the Portia White Prize, valued at $25,000, that is awarded each year to an artist who has achieved cultural and artistic excellence in her or his discipline.

New generations now learn about her. Talented artists from all disciplines benefit from awards given by the Nova Scotia Talent Trust, which began as the Portia White Trust and which still exists today.

Portia White’s signature song, “Think on Me,” says:

When I no more behold thee, think on me

When hearts are lightest, when eyes are brightest,

When griefs are slightest, think on me.

More than a century after her birth, people like me are still thinking about her.

Thanks to Section 25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canada became the first country in the world to recognize multiculturalism in its Constitution. With your help, we can continue to share voices from the past that were previously silenced or ignored.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!