Path of Most Resistance

I had only a sketchy recollection of the “Northwest Rebellion” — the armed uprising of 1885 led by Métis leader Louis Riel — when I drove an hour north of Saskatoon to visit the Duck Lake Historical Museum.

I soon learned much more as museum director Celine Perillat took me on a tour of some of the main sites of the resistance.

“Although the Northwest Rebellion stretched from Winnipeg to Alberta, most of the action took place here in Saskatchewan,” Perillat said as we drove a short distance west from the town of Duck Lake to a field with a cairn and plaque commemorating the small skirmish that touched off the rebellion.

At the Battle of Duck Lake, Métis fighters led by Gabriel Dumont, Riel’s military commander, overwhelmed a group of North West Mounted Police (NWMP), causing the latter to retreat.

As we drove farther west, passing vast yellow fields of canola, Perillat explained what had given rise to the rebellion. Métis people who had settled on land in what is now Saskatchewan were threatened by newly arriving settlers from eastern Canada.

When Riel asked the government to protect Métis rights, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald refused. Facing the loss of their land and their survival as a distinct people, the Métis rose up, forming a provisional government led by Riel.

In a parallel tragic story, the First Nations were suffering from the influx of settlers, the ravages of smallpox, and the depletion of the once-vast buffalo herds.

Furthermore, the government was not honouring Treaty 6, a major agreement between the Crown and a number of Aboriginal tribes on the prairies. Thus, many Aboriginals joined Riel and the Métis in their struggle. In response, Macdonald sent troops west to quash the uprising.

“I think Louis Riel was misunderstood,” mused Perillat, who is part Métis, as we travelled to our next stop. “He was treated as a villain, but many feel he was a hero.”

We arrived at Fort Carlton Provincial Park, the site of a restored Hudson’s Bay Company trading post, which also served as a base for the NWMP.

While there, we wandered along the wooden palisades, spoke with interpretive staff, and touched artifacts such as buffalo hides, beaver skins, war clubs, and birchbark baskets.

Next we drove east to St. Laurent de Grandin, an early Métis settlement and an annual pilgrimage site for its Our Lady of Lourdes shrine.

Many religious miracles have been reported at the shrine, with numerous people believing themselves cured by the spring water that flows from the hillside.

The settlement’s cemetery is the final resting place for four Métis fighters who fell in the Battle of Duck Lake. “Look,” said Perillat, pointing to a Métis flag flapping in the wind. “That shows the memory of the rebellion is still alive.”

Outside of Saskatchewan, however, the event is less well known. In part to address this, Tourism Saskatchewan and several partners have embarked on a project, called Trails of 1885, to signpost each of the twenty or so key sites connected with the uprising. The project, which will span three provinces and include maps and guides, was expected to be completed by late 2014.

“The Trails of 1885 is nationally significant and … will, we hope, attract visitors from around the world,” said Mark England of Tourism Saskatchewan.

I silently vowed to someday explore the entire route, which approximately traces the Carlton Trail, a major transportation route in the 1800s, along which Red River wagons rumbled between Fort Garry (Winnipeg) and Fort Edmonton.

In the meantime, I decided to join a one-day canoe tour — the River Trails of 1885, offered by CanoeSki Discovery Company — which visits many of the rebellion sites along the South Saskatchewan River north of Saskatoon. We launched two canoes, and soon the fast-flowing river carried us to Middleton’s Camp, a large grassy area marked by a lonely cairn.

“Major-General Middleton’s forces,” said our guide, “camped here for two weeks to regroup after the Battle of Fish Creek, also known as the Battle of Tourond’s Coulee.”

We paddled on, soon arriving at the battle site, where Dumont’s forces ambushed a larger government force and made them retreat. Trails mowed in the grass led us to a lookout with long views onto the river and the surrounding prairie.

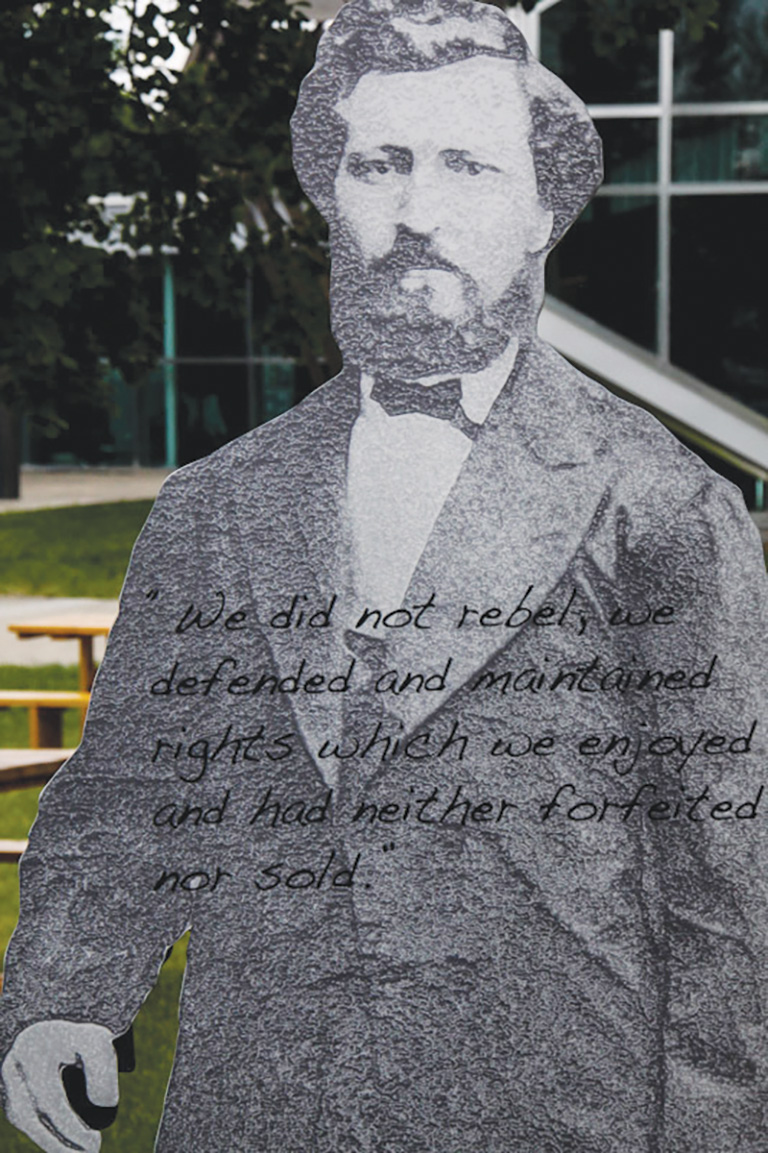

Metal cut-out figures representing Métis and government soldiers were arrayed on the valley side, so we could imagine the battle that raged here in April 1885.

Back on the water, we enjoyed the sight of pelicans, ospreys, and wildflowers. We stopped at Petite Ville, an abandoned Métis hivernant, or winter village, and munched on Saskatoon berries.

After twenty-three kilometres of paddling, we arrived at the once thriving but now abandoned village of Batoche, a National Historic Site.

At the white-sided rectory, a guide in period costume pointed to holes in the wall.

“These were made by the much-feared Gatling gun. The government forces also used cannons and cavalry.”

I gulped as I envisioned the position of the Métis, who, fighting with rifles and little ammunition, were outgunned and outnumbered. They were defeated in this final battle of the resistance.

In the cemetery, graves and crosses mark the dead of both sides. Riel surrendered a few days after this battle and was eventually hanged.

That evening I nursed an ale and thought about the rebellion, Riel, and the parts of the Trails of 1885 I still had to visit. The western part called to me, especially the site of the Frog Lake uprising where Cree warriors, encouraged by the Métis victory in the Battle of Duck Lake, attacked Frog Lake village on the eastern edge of what is now Alberta, killing nine settlers.

I also yearned to visit Manitoba and tour Winnipeg’s St. Boniface Museum, and stand silently at Riel’s grave in the cemetery beside the St. Boniface Cathedral. Perillat’s words echoed in my mind: “Riel should never have been hanged.”

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement