It Is Pictured

With a strong prairie wind buffeting our backs and a hot southern-Alberta sun baking our arms, my daughter, Alaina, and I float down the tranquil Milk River in our kayaks. The river quietly sweeps us past sheer sandstone cliffs that reach into the pale prairie sky, while swallows dart overhead, tacking across the wind like tiny sailboats.

At the bottom of the Milk River Valley, surrounded by the mixed-grass prairie of southern Alberta and with only the birds in sight, we feel utterly alone but certainly not lonely. After all, we’re in the middle of Writing-on-Stone / Áísínai’pi — a provincial park, a National Historic Site, and a UNESCO World Heritage Site all rolled into one impressive place.

This is a land with a long memory. Archaeological sites show that Indigenous people have been visiting Writing-on-Stone /Áísínai’pi (Blackfoot for “it is pictured” or “it is written”) for more than 3,500 years. However, people have likely been coming here for much longer than that, as the oldest archaeological sites in this corner of southern Alberta date back ten millennia.

Today, Writing-on-Stone / Áísínai’pi is a living cultural landscape that remains sacred to the Siksikáítsitapi (meaning Blackfoot-speaking real or original people) of the Blackfoot Confederacy: the Kainai, the Piikáni, and the Siksika First Nations. As long as the Niitsítapi (the Blackfoot term for themselves and other Indigenous people, meaning original or real people) have been on the Great Plains, they have travelled here to communicate through ceremonies and vision quests with the sacred beings that dwell among the hoodoos and the sandstone cliffs.

A short distance from where we float alongside the pale-yellow cliffs is the largest concentration of Indigenous rock art on the Great Plains. At night, after our float down the Milk River, we settle around a campfire under a star-filled sky. The soft murmur of voices and the pop and crackle of nearby campfires drift through the campground.

In the morning we join a guided tour of the archaeological preserve, a restricted area where most of the rock art is found. The tours, often led by Siksikáítsitapi guides, are the only way to see the concentration of petroglyphs (rock carvings) and pictographs (painted images) in the park and are the best way to learn about them. Interpretive displays in the visitor centre further explore the history and meaning of rock art, along with the history of the Siksikáítsitapi, the North West Mounted Police (NWMP), and the settlers who established farms and ranches in this area in the mid-to-late 1800s.

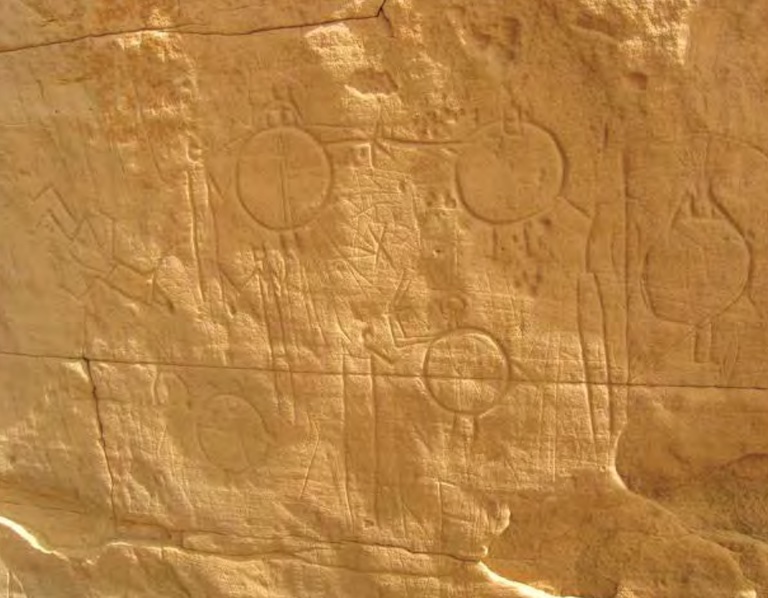

Our guide leads the group along a trail that begins near the rodeo grounds where we started our river float the day before. We follow an undulating cliff, passing numerous panels of well-preserved petroglyphs and pictographs of abstract shapes and recognizable images, such as bison, horses, and numerous shield-bearing warriors and human figures with V-shaped necks or triangular bodies.

We learn that the rock art — most of which dates back between roughly a thousand years and a century ago — records events, personal achievements, dreams, and visions. It’s believed that the oldest petroglyphs in the park were crafted some three thousand years ago.

The arc of Great Plains history written on the rocks stretches from the days when dogs were the only domesticated animal in use in North America, through to the introduction of horses and guns in the early-to-mid 1700s. It continues through the arrival of the police and the settlers, ending relatively recently with the automobile’s appearance in the West, which was documented on the rocks in 1924 by Bird Rattle, a Piikáni Elder.

While many of the petroglyphs and pictographs stand alone as single images, others tell elaborate stories, such as the battle scene. Accessible via a short trail from the park’s public road, this panel features 250 petroglyphs that are said to document a battle the Siksikáítsitapi fought against the Crow, Gros Ventre, and Plains Cree near the Milk River in 1866.

Even though the battle scene petroglyph is accessible without a guide, it is fenced off to protect it from vandals. Alberta Parks is actively removing graffiti from the cliffs. Damaging the rock art or defacing the cliffs, hoodoos, and rocks in the park can lead to large fines (up to $50,000) and a year in jail.

Across the valley from where we sit immersed in the history and culture of the Siksikáítsitapi, we can see the 1975 reconstruction of the NWMP post. Its white walls stand in sharp contrast to what we experience on the north side of the river among the rock art — settler law and order juxtaposed with ceremony and reverence. The NWMP established a camp facing Police Coulee in 1887 to stop both cross-border raiding of horses by the Kainai and whisky smuggling into First Nations. The Mounties built the barracks in 1889, and the post closed in 1918.

Soon after the police established their post, settlers began farming and ranching in a region whose original inhabitants had been removed — they had been confined to reserves following the 1877 signing of Treaty Seven. However, the farmers and ranchers embraced Writing-on-Stone / Áísínai’pi, and their stewardship led to its being protected as a provincial park in 1957. The park was named a National Historic Site in 1995 and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2019.

Today, Alberta Parks manages Writing-on-Stone / Áísínai’pi with advice from Siksikáítsitapi Elders. The Siksikáítsitapi continue to practise their traditions and ceremonies in the heart of their ancestral lands. They share their ancient connections to this sacred landscape with non-Indigenous people such as me and my family, and each successive visit has left us with a deeper appreciation for the people of this remarkable place.

IF YOU GO

GETTING THERE: Writing-on-Stone / Áísínai’pi is located in south-central Alberta just north of the Canada-U.S. border. The park is a 3.5-hour drive from Calgary by way of Lethbridge and the town of Milk River. From Milk River, it’s a thirty-minute drive east to the park via Highway 501.

WHERE TO STAY: Camping is available in the park, and sites can be reserved on the Alberta Parks website. Five private campgrounds are available within a forty-five-minute radius of the park; they’re located at or near the communities of Foremost, Milk River, and Warner. Hotels and motels are also located in Milk River.

EXPLORE: Hike the 4.4-kilometre Hoodoo Interpretive Trail to learn about the natural and cultural history of Writing-on-Stone / Áísínai’pi.

BRING: Services in the park are limited, so bring food and plenty of water. Summertime temperatures can reach forty degrees Celsius.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement