Inventing a 'Friendly Neighbor'

The Great Depression was a nervous time for Canada’s tourism industry. From 1929 to 1933, revenue from tourist traffic in Canada fell by more than half, and even visits to iconic national parks stagnated. By 1934, an industry already in flux — thanks to private car ownership that shook up leisurely old routines based around trains, steamboats, and resort hotels — now faced a crisis.

Worried Canadians called for a public inquiry, which the Senate conducted in 1934. Predictably, the Special Committee on Tourist Traffic recommended a stimulus package — an emergency program of public spending on parks, highways, and publicity. The program was to be consistent with a “fair and reasonable enforcement of regulations and the welfare and dignity of the country generally,” said the committee’s report.

Dignified or not, new staff and new ideas were needed to rebrand Canada as a “friendly neighbor.” The government quickly poached New Brunswick’s chief tourism officer, Leo Dolan, a bright, able man who was at ease in all the necessary circles. After a change of government in 1935, Dolan found himself working under a public servant who was as dynamic as himself — C. D. Howe, the American-born minister of railways and canals.

Dolan would spend the next thirty years promoting Canada, first as director of the tourism bureau, and later as consul-general in Los Angeles. In 1935, he sat down with Toronto advertising genius Jack MacLaren to dream up new ways to brand Canada. Enough survives in the official records to show flashes of enthusiasm and easy relations between Dolan and MacLaren’s team, as well as occasional tight-lipped reminders that this was, after all, government work.

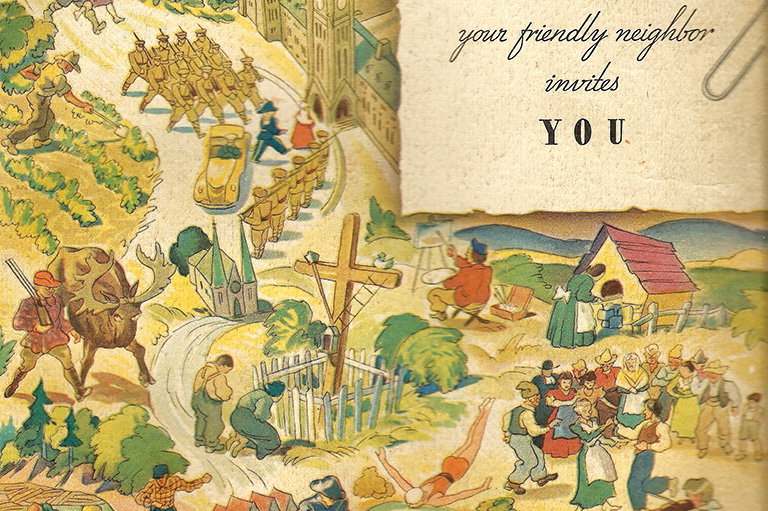

The resulting collaboration was a colourful forty-eight-page booklet, aimed straight at the American market. The title, Canada, your friendly neighbor invites you (with neighbour spelled the American way), borrowed a description U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt had used during trade negotiations. The “friendly neighbor” that emerged was more sophisticated than the notorious marketing blend of moose and Mounties. The new characterization of Canada merged boundless but safe wilderness with historic cities — a mixture which was mildly exotic, yet free from danger for the travelling family. Moose and Mounties do not dominate the medley of impressions the booklet’s images provide: Forts and public buildings are solid and impressive, bears are as common as automobiles, fish are plentiful, and only men wear two-piece bathing suits.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Civil servants wrote the text for the booklet, which MacLaren’s team enlivened with an attractive layout and original artwork. The target audience was the upscale professional American man who was invited on page three to renew his zest for living by “turning the key in the office door for a few weeks this year” and bringing his family to Canada. “Next winter,” this fictional American was advised. “You’ll be glad you said: ‘Good-bye, desk, I’m going North.’”

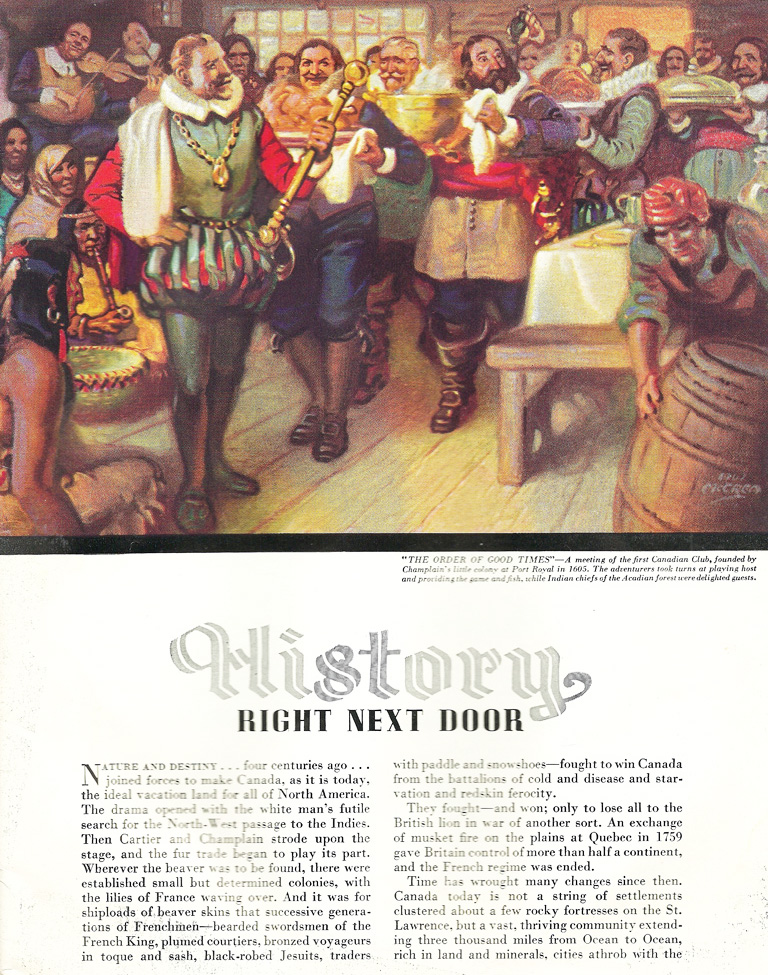

MacLaren’s men drafted this breezy invitation, but lost their fight to print it in a woman’s handwriting and sign it “Janey Canuck.” This was too folksy for Dolan, who “hated” the stereotype of Jack Canuck and believed it offensive to “a certain element of our population in Canada” (presumably meaning French Canadians). The deputy minister agreed, and Janey Canuck was banished. The letter appeared unsigned and unaddressed, and the ad men’s suggestions to address it to “Dear Uncle Sam,” “Dear Cousins,” or “Dear Neighbor,” were also quashed. It was placed on a page that faced a painting called The Order of Good Times — representing the social club established in New France by Champlain in 1606. Thus the “dignity of the country generally” was preserved.

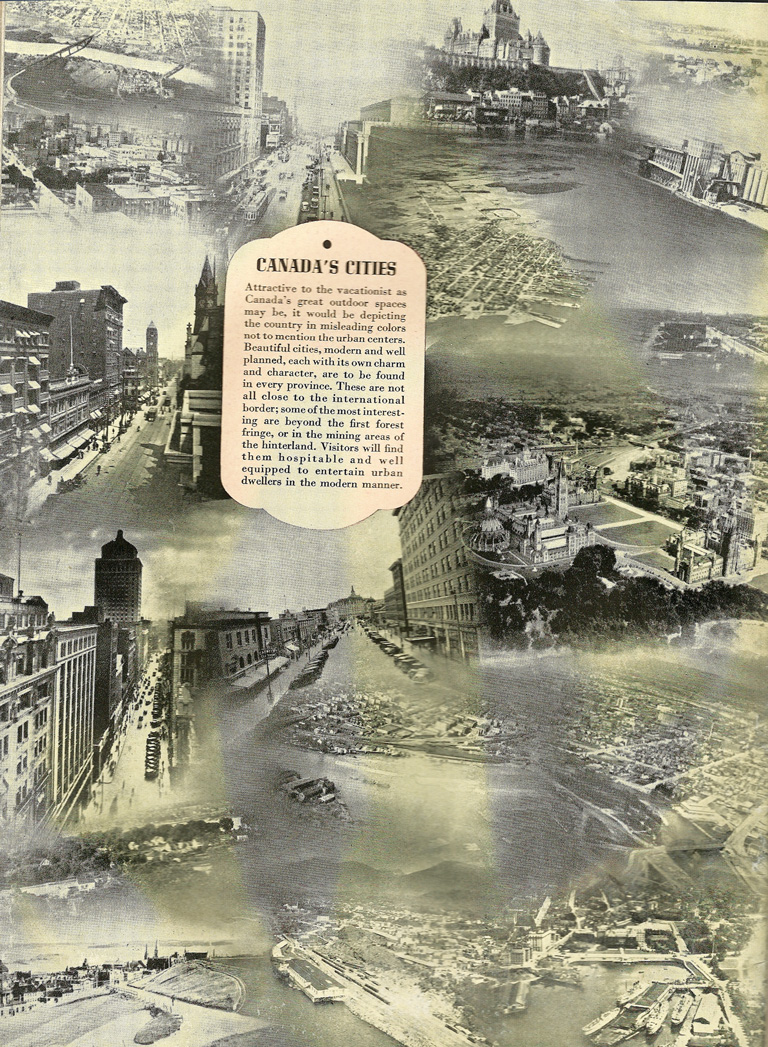

The more serious approach also influenced the choice of “History Right Next Door” as the first of twenty short articles in the booklet. The second article featured Canada’s national and provincial parks. More tales of heritage followed in a twopage spread on capital cities and parliament buildings. In the final cultural contribution, “Stories in Stone,” National Parks staff extolled the country’s historic sites alongside photos of many of eastern Canada’s best-loved attractions. These included Louisbourg and Grand Pré in Nova Scotia, and the Basilica of Ste. Anne de Beaupré in Quebec. The story was accompanied by a timeline of sixty-four important events in Canadian history.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

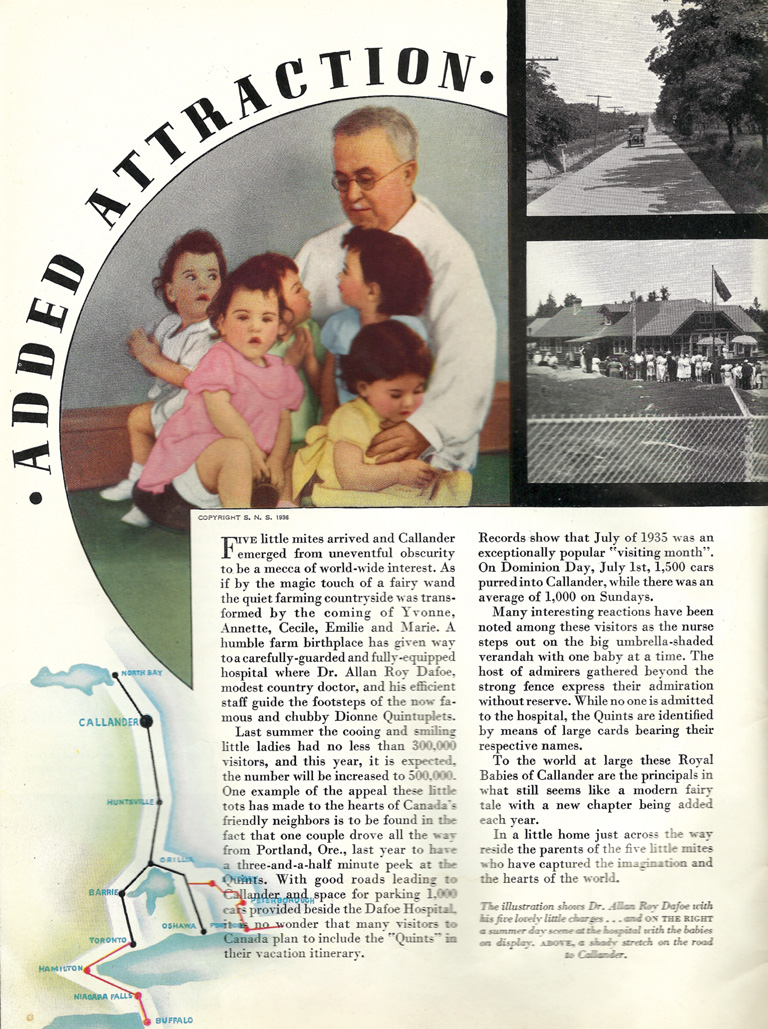

Also inside were articles on travel by rail, road, and steamboat, two short pieces on border formalities, and eleven articles on outdoor sports and recreation. An essential ingredient was a feature on the “Royal Babies of Callander” — the Dionne Quintuplets — whose cooing and smiling, promoters hoped, would draw half a million visitors a year to Quintland, north of Toronto.

The more serious approach also influenced the choice of “History Right Next Door” as the first of twenty short articles in the booklet. The second article featured Canada’s national and provincial parks. More tales of heritage followed in a twopage spread on capital cities and parliament buildings. In the final cultural contribution, “Stories in Stone,” National Parks staff extolled the country’s historic sites alongside photos of many of eastern Canada’s best-loved attractions. These included Louisbourg and Grand Pré in Nova Scotia, and the Basilica of Ste. Anne de Beaupré in Quebec. The story was accompanied by a timeline of sixty-four important events in Canadian history.

Also inside were articles on travel by rail, road, and steamboat, two short pieces on border formalities, and eleven articles on outdoor sports and recreation. An essential ingredient was a feature on the “Royal Babies of Callander” — the Dionne Quintuplets — whose cooing and smiling, promoters hoped, would draw half a million visitors a year to Quintland, north of Toronto.

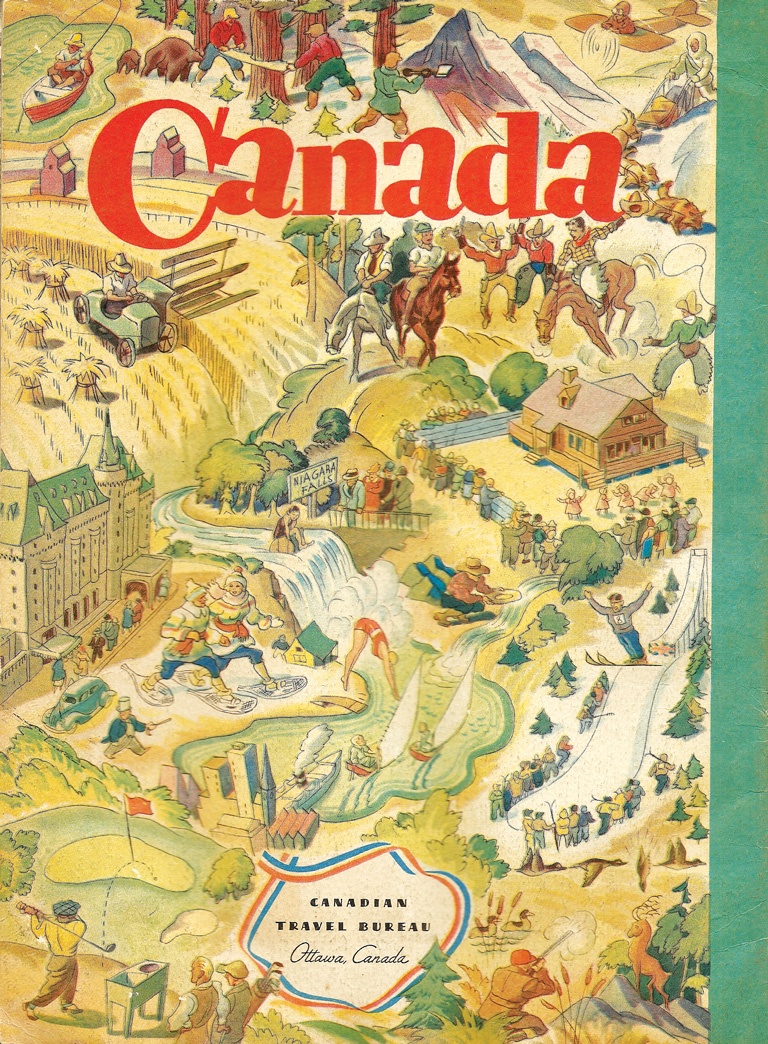

The masterpiece of the whole project was the wraparound cover painting. It featured a swarm of Canadians acting in stereotyped regional and occupational roles. They mostly ignore the sprinkling of young American couples doing hearty outdoor things within this “Where’s Waldo” scene. Jack Bush, who was then a twenty-six-year-old commercial artist with the Toronto graphic design firm of Bomac Engravers, did the artwork. Bush is now best known for his decisive move into abstract expressionist painting in the 1950s, but the cover of Canada, your friendly neighbor invites you must have been one of his most stimulating opportunities during the Depression.

“Although the pamphlet might be described as ‘camp’ by today’s standards, it won a design award nonetheless as part of the RCA [Royal Canadian Academy of Art] annual exhibition of 1938,” writes Michael Burtch in a 1997 exhibition catalogue entitled Hymn to the Sun.

Bush’s paintbrush imagined a Canada with numerous landmarks but no boundaries. The image has no real oceans and only the vaguest orientation of regional figures to where they ought to be. Appropriately, along the top edge a bush pilot and a dogsled suggest the North, and where New Brunswick should be, a fisherman in slicker and sou’wester is throwing his net to catch a diving woman in a red bathing suit. By contrast, at the foot of Niagara Falls a Klondike prospector pans for gold in a stream that winds away to Quintland. Mostly, the images jostle each other in a joyful rejection of conventional geography.

Advertisement

Two kinds of people inhabit this imaginary place. The Canadians are shown working and playing in about equal numbers. But they are completely uninvolved in industry — a typical evasion in this style of tourist promotion, which walks a tightrope, promising visitors modern conveniences while hiding the grittier evidence of modern life. Through this idealized tableau move the real stars — the anglers, the hunters, and the youthful American couples on holiday.

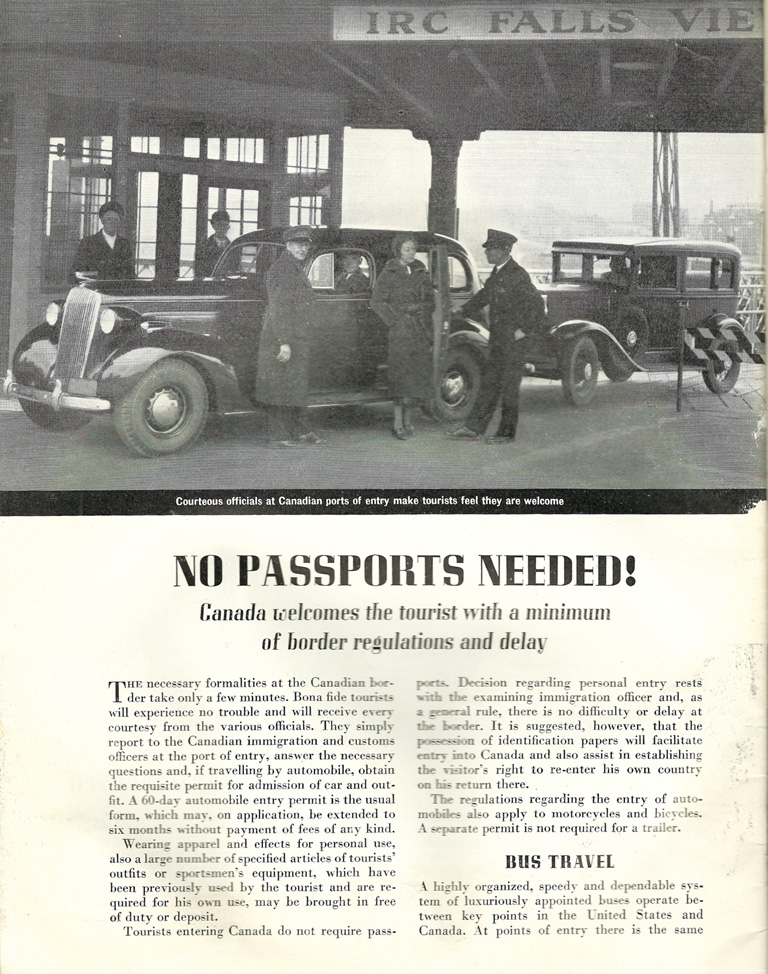

The booklet deals in an unthreatening way with the question of Canada as a foreign country. A high comfort level is suggested via a familiar list of public holidays, calming assurances about American currency being welcome, and an announcement that now sounds ironic: “NO PASSPORTS NEEDED! Canada welcomes the tourist with a minimum of border regulations and delay.”

Dolan had 150,000 copies printed at about thirty-three cents apiece. They were widely praised within the business and were distributed through a network of American contacts. Others were given away in railway cars in Canada and at other tourist haunts. No record has been found of a second printing. Three years after publication, the Second World War broke out, disrupting tourism and ushering in a new era with new ways of seeing and marketing the country. During its moment, however, Canada, your friendly neighbor was an eye-catching example of Canadians’ desire to attract Americans, while self-consciously reflecting who we imagined we were, or might want to be.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement