Gushing with pride

For Charley Fairbank, the oil-soaked lands of southwestern Ontario are more than just a bit of history. The black gold flooding up from beneath the ground is like the blood of his family, and Charley wants to transfuse that blood into the body of Canadian history.

Oil bubbled out of the ground in the area long before the Europeans arrived. Chippewa craftsmen used the pitch found around the communities of Oil Springs and Petrolia to waterproof their canoes and possibly as medicine to treat wounds.

When the first oilmen began to hand-dig wells in this southeast corner of Lambton County (about seventy kilometres west of London) they found deer horns and pieces of timber bearing the marks of the axe, and, in one spot along Black Creek, a new well under excavation cut into the remains of an ancient First Nations well.

“At a depth of twenty-seven feet from the surface, a pair of deer’s antlers were taken from this old pit,” Fairbank said.

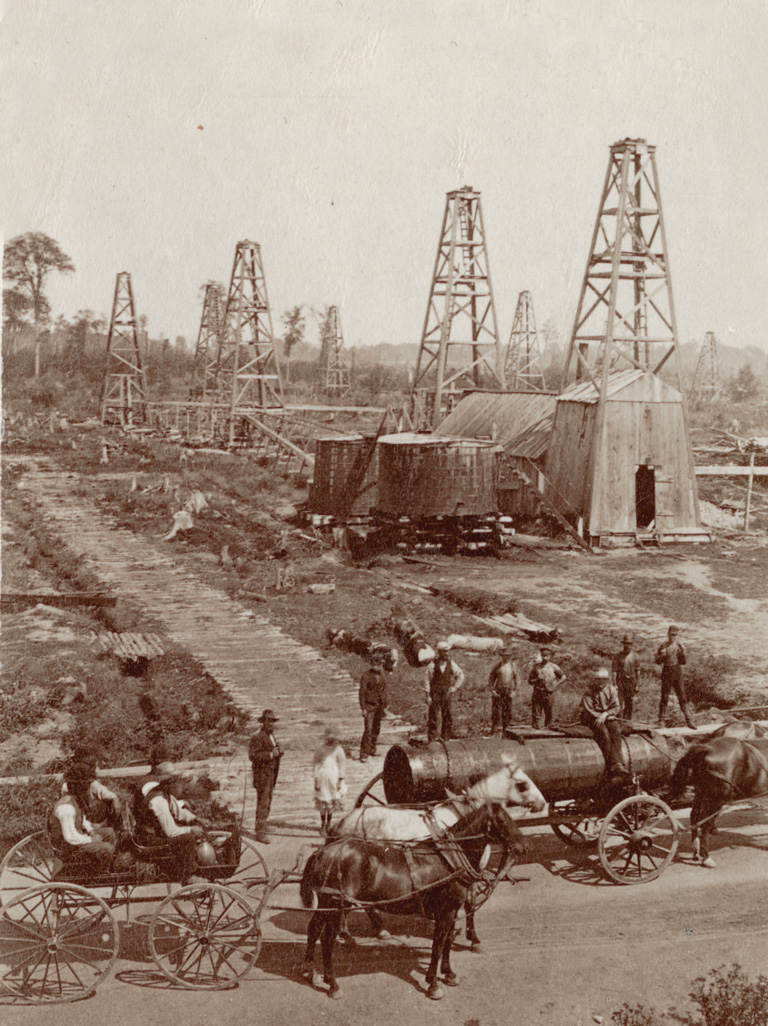

It was at Oil Springs that James Miller Williams dug the first commercial oil well in North America in 1858. Within months of his discovery, the oil rush was on. Fairbank’s great-grandfather arrived in 1861 and immediately bought land.

Today, Oil Springs is designated a national historic site, and Fairbank and his son, Charley IV, operate the oldest oil company in the world. The Fairbank family is one of the last of the oil clans still involved in an industry born in the 1850s muck and mire of Enniskillen Township.

With 350 operating wells, the 263-hectare Fairbank field produces twenty-four thousand barrels of crude annually. Even though Fairbank Oil is a commercial enterprise, Charley Fairbank is the head cheerleader promoting the birth of the oil industry as a tourist destination.

On what turned out to be the hottest day of the year, Fairbank and I hopped into his pickup. He wanted to show me his latest project, the Fairbank Oil Nature Trail, which is part of the Oil Patch Driving Tour.

Every generation of Fairbank growing up on the property was keenly aware of its diverse species. Deer, monarch butterflies, frogs, muskrat, and beaver as well as a host of insects and reptiles live here.

When he shuts off the truck’s diesel engine, the sound of a rhythmic creaking accompanied by the scent of raw crude rides the wind into the cab. Contrary to popular opinion, the smell of oil isn’t offensive, just a departure from everyday aromas.

From the walkway above Black Creek, Fairbank points out cardinal flowers and about a dozen rare species of plants growing in the creek mud. He also indicates an overgrown earthen mound. “That’s a precontact First Nations mound,” he said. “There are six of them. We haven’t excavated it yet, so we’re going to work with the local band to protect it and research it.”

Archaeologists, I thought to myself, would have a field day here. Turns out they already have. Dr. Emory Kemp, a renowned industrial archaeologist from West Virginia University, has already visited these oil fields to look at the technology, causing Fairbank to quip, “It was as if they had been studying dinosaur fossils and stumbled on a living, breathing dinosaur.”

Technology is a key part of the driving tour. Jerker lines that power the wellhead pumps provide a creaking soundtrack. It is nineteenth-century technology that still works incredibly well.

We stop at a life-sized outdoor diorama of sculpted steel representing five men and a horse. The sculpture illustrates a drilling crew operating a cable tool drill rig, which was the original technology for sinking a well and is still in use today.

Dozens of these steel folk art figures populate the landscape.

While we’re stopped, Fairbank tunes his radio to a station listed on the driving guide, and we pick up a broadcast giving information about the display.

There are nine stops with audio presentations tied to them; the first stop is the Oil Museum of Canada, where you can get your bearings and tune your radio.

The indoor and outdoor displays on the oil museum’s four-hectare site contain a wealth of information about the birth of the North American oil industry.

Inside the museum, which became a National Historic Site in 2004, there is a theatre with audiovisual screenings; a main gallery details life in the pioneering days of the first oil explorers; the Oil Springs gallery focuses on the discoveries, exploration, and development of the fields immediately surrounding Oil Springs; and the foreign drillers gallery tells the stories of local men who travelled the world drilling for black gold using Canadian technology.

The daughter of one Oil Springs driller married the legendary Count von Zeppelin. Another drilling family found itself trapped by the Russian Revolution in 1918 and made its escape overland in farm wagons and on horseback from Grozny, on the Black Sea, to Murmansk, in the Russian Arctic, where it continued its journey home aboard a British troop ship.

A visit to the Oil Museum of Canada can take you the better part of a day, but it’s well worth it.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement