Cannibal Cruise

After the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, England was a rising maritime power, flush with success and pride. Trade was increasing, merchants were searching for a route to the Orient and the Spice Islands, and English privateers were plundering Spanish ships in the West Indies.

It was the dawn of a golden age of prosperity and expansion for England, and interest and pride in the nation’s seafaring past increased dramatically.

A young scholar and cleric named Richard Hakluyt was busy gathering all the information he could for a monumental compilation of the tales of past English maritime prowess. He spent years at this task, travelling the country and interviewing mariners, sea captains, merchants, and adventurers. As an archivist and editor, he preferred verifiable firsthand accounts, eyewitnesses, and official documents.

On one occasion, just before publication in 1589 of the first edition of his work The Principal Navigations Voyages Traffiques & Discoveries of the English Nation—Made by Sea or Over-land to the Remote and Farthest Distant Quarters of the Earth at any time within the compasse of these 1600 yeeres, he rode over three hundred kilometres from his home in Oxford to interview the last remaining survivor of a little-known voyage to the Newfoundland and Labrador coast.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The elderly man’s name was Dr. Thomas Buts, and the voyage took place in 1536, at the dawn of the days of English transatlantic voyaging half a century earlier.

From Buts, Hakluyt learned “the whole trueth of this voyage from his own mouth, as being the only man now alive that was in this discoverie.”

The only other corroboration of Buts’s improbable tale came from a gentleman named Oliver Dawbeny, who was interviewed around the same time by Hakluyt’s cousin. After the passing of fifty years, neither of the men could recall the precise details of the voyage, and their accounts as recorded by Hakluyt are somewhat sketchy, leaving many questions unanswered. But it is possible to piece together an outline of one of the most unlikely and unlucky expeditions to what is now the Canadian Atlantic coast ever to have occurred during the Age of Discovery.

It was an unimportant voyage that accomplished little in terms of geographical discovery, but for those mariners who participated it was a terrifying ordeal benighted by starvation, cannibalism, and piracy.

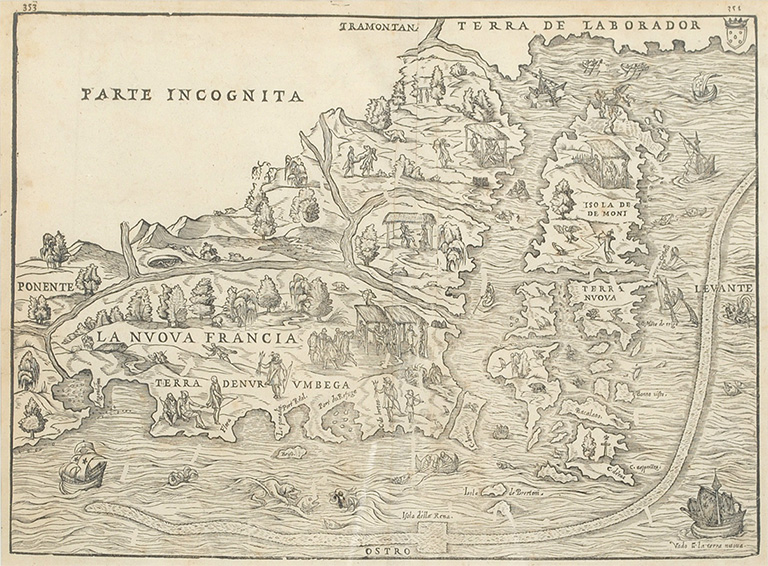

Since John Cabot’s voyage across the Atlantic in 1497, and perhaps even earlier, English mariners had been frequenting the Grand Banks of Newfoundland to fish for cod. Geographical knowledge of the coast, however, was as scant as our current knowledge of the surface of Mars.

Only recently had European cartographers agreed that the land was not the fabled coast of the Orient or Spice Islands and was indeed an entirely new continent. In January 1536, when a London leather merchant and experienced sea captain named Richard Hore proposed a tourist expedition to the New World, it seemed like a grand and exotic adventure.

Hore, who was, according to Hakluyt, “a man of goodly stature and of great courage, and given to the study of Cosmographie,” probably drew inspiration for his scheme after hearing of Jacques Cartier’s successful voyage to the St. Lawrence in 1534, and after observing the excitement generated by the return of William Hawkins from South America in 1535 with “one of the savage kings of the countrey of Brasill.” Hawkins paraded the hapless man around London, drawing crowds of astonished spectators.

Hore realized that he could outfit an expedition of dual purposes to reduce the financial risk-while one ship loaded up on codfish, the other would cruise about the coasts with a complement of English gentlemen. Perhaps if they were lucky, they too could capture an Indigenous person to be displayed, for a modest fee, to the curious masses.

It would be a dangerous and possibly foolhardy voyage, without maps of the coast, sailing cumbersome, top-heavy Tudor ships loaded with coddled gentlemen with no sea experience. There was always the chance that they would become lost or burst asunder on the jagged coastal rocks hidden by the swirling waves of the turbulent north Atlantic.

But Hore was a tireless promoter of the venture and, when King Henry VIII blessed the outlandish scheme with “favour and good countenance,” dozens of gentlemen expressed interest in the exciting voyage.

Hore’s “persuasions tooke such effect” that “many gentlemen of the Innes of court, and of the Chancerie, and divers others of good worship, desirous to see the strange things of the world, very willingly entered into the action with him.”

Between January and March 1536, thirty gentlemen sightseers had signed on for the adventure of their lives. The tourists included many proud and wealthy members of the English court, including M. Weekes, “a gentleman of the West countrey of live hundred markes by the yeere living”; M. Tucke. “a gentleman of Kent”; M. Thomas Buts, “the sonne of Sir William Buts knight of Norfolk”; M. Armigil Wade, “a very learned and vertuous gentleman ... afterwards Clerke of the Counsailes of king Henry the 8 and king Edward the sixth”; M. Oliver Dawbeny, “merchant of London”; and “divers other of good account.”

In addition to the gentlemen, there were around ninety sailors, bringing the total number to 120 on two small ships, the William and the Trinity. Richard Hore apparently sailed in one of the vessels himself.

Advertisement

After mustering the crowd “in warlike manner at Gravesend, and after the receiving of the Sacrament,” the two ships slipped their mooring and sailed down the Thames into the Channel and headed west across the ocean. It was the end of April 1536.

The Atlantic crossing must have been a terrible ordeal for wealthy gentlemen without naval experience and unaccustomed to cramped quarters on drafty ships with little other than salt pork, hardtack, and flat beer for provisions. Hakluyt records that the ships were “very long at sea ... above two moneths, and never touched anyland untill they came to part of the West Indies about Cape Briton.”

They sighted what they suspected was Cape Breton, the northern promontory of Nova Scotia, and steered northeastward around the southeastern tip of Newfoundland, following the rugged coast north until they sighted the “Island of Penguin”—now called Funk Island, off the northern coast of Newfoundland.

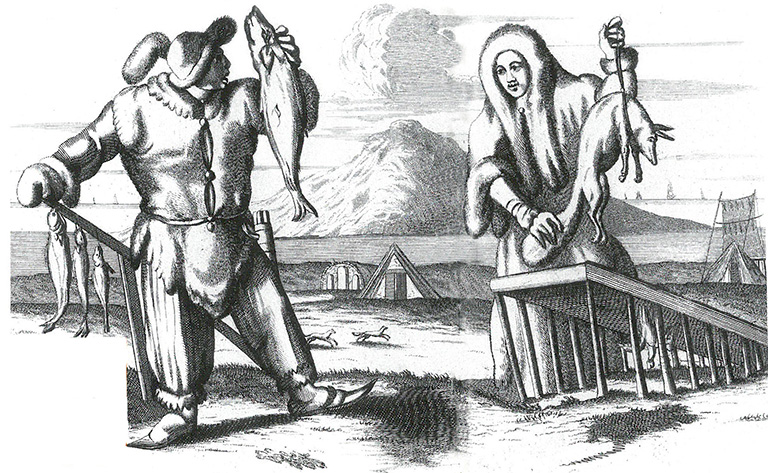

The desolate promontory, “very full of rockes and stones,” had been visited by Jacques Cartier two years earlier and was a regular stopping point for fishing vessels. This voyage was no exception. The island was “full of great foules white and gray, as big as geese, and they saw infinite numbers of their egges.”

The birds were the flightless great auks, large and easy to catch. Along with other sea birds of Funk Island, the auk was a reliable source of food for thousands of mariners over the centuries until by the mid-nineteenth century it was driven to extinction.

The crews of the Trinity and the William rowed small boats to shore and “drave a great number of the foules into their boats upon their sayles, and tooke up many of their egges.” The sailors prepared them for eating by plucking the feathers, apparently an annoying job as “their skinnes were very like hony combes lull of holes being Head off.”

When the work was done, they cooked up a great least of the sea birds, probably roasting them over a fire, and declared them “very good and nourishing meat.”

It was no doubt a great treat after over two months of hardtack and biscuit. On Funk Island they also spied several “beares both blacke and white,” which they hunted with their guns and “tooke them for no bad foode.”

After the communal feast and replenishing of fresh food supplies, the two ships separated. While the William loaded with sailors and fishers, cruised to the Grand Banks to load up on codfish, the Trinity sailed off into unknown waters for adventure and to hunt and capture an indigenous person from the area.

Not long after, the Trinity was anchored in a bay, unable to leave. Although it is unclear exactly where the Trinity sailed, historians such as Davis Beers Quinn suggest that the most likely destination was the Strait of Belle Isle en route to the St. Lawrence, while others have suggested that the ship quickly put in to a nearby harbour on the northern Newfoundland coast.

The accounts of the voyage recorded by Hakluyt offer no clues to explain why the Trinity became stranded along an unknown shore, but storms may have damaged the vessel beyond repair, or the ship may have run aground on hidden coastal rocks.

Most of the skilled and experienced mariners were probably on the William, leaving the Trinity with a large contingent of gentlemen who had no practical knowledge of nautical matters.

In either case, the Trinity was in harbour somewhere along the Newfoundland or Labrador coast when Oliver Dawbeny, strolling the upper deck, caught sight of a boat being rowed slowly and cautiously from the shore toward the ship.

The “natural people of the countrey, that they had so long and so much desired to see,” were likely paddling a bark or skin canoe on a fishing or birding expedition. Dawbeny was very excited, and after yelling to his comrades below deck, he and some crew “manned out a ship-boat to meet them and take them.”

But the wary locals, perhaps detecting the sinister motives of the English gentlemen, “returned with maine force and fled into an Island that lay up in the Bay or river there, and our men pursued them into the island” where they escaped.

After thrashing around through the evergreen forest for several hours, the troupe stumbled upon “the side of a beare on a wooden spit” at the locals’ campsite.

Perhaps they ate some of the roasting bear before continuing their search. But the only other items of interest they could plunder from the camp were “a boote of leather garnished on the outward side of the calfe with certaine brave trailes, as it were of rawe silke, and also found a certaine great warme mitten.”

(Probably an Inuit design, reinforcing the notion that they were either harboured along the northern Newfoundland coast or the southern Labrador coast.) The downcast gentlemen returned to the ship with these intriguing curios but without a human captive.

The ship remained in harbour for a considerable time, likely several weeks, until “they grew into great want of victuals.” Perhaps the stores had inadvertently been transferred onto the William before the two separated, or perhaps their stores had gone mouldy or rancid.

Apparently, the Trinity was also bereft of any fishing gear – it, too, must have all been loaded onto the William – and the stranded men “found small reliefe” from the land.

For a brief period of lime, the crew and gentlemen, numbering as many as forty or fifty individuals, stole fish from the fledglings in the nest of a nearby osprey “that brought hourely to her yong great plentie of divers sorts of fishes.”

But the famine, Dawbeny related, increased daily until “they were forced to seeke to relieve themselves of raw herbes and rootes that they sought on the maine.”

The land proved inhospitable, barren and devoid of life. Hunting parties failed to return with anything edible, and the men went ashore and spread out, ranging through the stunted shrubs and wind-lashed trees for anything edible. They grew weak, fearful, and demented as they withered away on a diet of roots and herbs.

Stranded along the desolate coast, slowly starving, they resorted to the final indignity. “In the fieldes and deserts here and there, Dawbeny remembered, “the fellowe killed his mate while he stooped to take up a roote for his reliefe.” Alter concealing the body and “cutting out pieces of his bodie whom he had numbered,” a lire was lit and the flesh “broyled ... on the coles and greedily devoured.”

Slowly men went missing, and the officers speculated that they had been “devoured with wilde beastses,” or “destroyed” by the local population. The account doesn’t specify whether the missing men were sailors or gentlemen.

On one occasion, however, a starving man scratching in the stony earth for herbs smelled “the savour of broyled flesh” and drew near to a man huddled over a small fire. The two fell into a violent quarrel, the one accusing the other of secretly holding food while the others languished.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

They soon fell into “cruell speaches,” as one claimed that the other “would stiller him and his fellowes to sterve, enjoying plentie as lie thought. The guilty man, according to Dawbeny, then passionately shouted: “If thou wouldest needes know, the broyled meate that I had was a piece of such a mans buttocke.”

The shocking news was delivered to the captain, possibly Richard Hore himself, who in dismay and perhaps disgust harangued the starving men with “a notable Oration”, wherein he “vouched the Scriptures from first to last,” and proclaimed that “these dealings offended the Almightie.”

He beseeched them to pray lor deliverance from their miserable predicament and reminded them that “it had been better to have perished in body, and to have lived everlastingly, than to have relieved for a poore time their mortal bodyes, and to be condemned everlastingly both body and soule to the unquenchable fire in hell.”

He began to “exhort” repentance and “besought” them to pray for the intervention of God “for his owne mercie to relieve the same.” Apparently the men were shamed into stopping their cannibalistic feasting.

But despite the pitiful pleas to their God, the famine continued unabated until, driven to despair, the entire company agreed that “rather then all should perish, to draw lots who should be killed.” They would draw straws to select the sacrifice for the evening’s meal.

It was probably nearing the end of September. The first round of their morbid game had not taken place, however, before a ship was spied on the horizon.

It proved to be a French fishing ship “well furnished with vittaile.” Whether the French offered assistance will never be known, but the starving English mariners resolved on a bold plan of action, “and such was the policie of the English, that they became masters of the same and. changing ships ... they set sayle to come to England.”

Apparently, they stole the French ship and abandoned the French sailors with the damaged Trinity.

The return voyage in the captured ship was an adventure in itself. The astonished gentlemen “sawe mighty Islands of yee in the summer season, on which were haukes and other foules to rest themselves being weary of flying over far re from the maine.”

After a month of sailing, they arrived in England at the end of October and put to shore at the first port they came to — St. Ives in Cornwall. Being so weary and emaciated from the journey, the gentlemen did not travel far.

They recuperated “and were very friendly entertained” at “a certain castle belonging to sir John Luttrell”, before slowly pressing on overland to London.

It was at this castle that Thomas Buts, whom Hakluyt interviewed later in life, “was so changed in the voyage with hunger and miserie, that sir William his father and my Lady his mother knew him not to be their sonne, untill they found a secret marke which was a wart upon one of his knees.”

Neither Buts nor Dawbeny in their accounts related by Hakluyt give any indication of how many perished on the expedition, or whether it was mostly mariners or gentlemen who survived the return journey.

After they were nursed back to health, the survivors expected to suffer punishment or social reproach for killing their comrades in their desperation. But far from being angry Henry VIII was sympathetic and, “mooved with pitie, punished not his subjects.”

Advertisement

When the French sailors cruised into London in the Trinity several months later, the king “out of his own purse made full and royall recompence unto the French. He also ordered their ship returned to them. Hakluyt records no more details of the adventure, but other court records in England reveal that Richard Hore came into trouble of a different sort.

His business partners accused him of stealing their share of the codfish brought back by the William, which had returned to London in September. He was also sued by the owner of the Trinity and the William, who claimed they were severely damaged during the voyage.

Hore’s disastrous expedition put to an end all official English voyages of discovery to the New World for over a quarter century, and ended the Newfoundland tourist business for the next two hundred years.

The historian David Beers Quinn wrote that “the adventure certainly gave some educated Englishmen a view of the New World, but it was a sufficiently unfavorable one to act as strong negative propaganda for further North American exploring expeditions.”

Fortunately, tourist cruises to bird sanctuaries and for whale watching along Newfoundland’s ruggedly beautiful coast are now popular and common, and starvation, cannibalism, and piracv are relegated to the distant past. Funk Island is now a wildlife preserve, and the scene of the piteous suffering and desperation of the men of the Trinity lies in one of the thousands of inlets and sheltered coves along the Newfoundland or Labrador coast. It will probably never be found.

Thus ends the tale of “The voyage of Master Hore and divers other gentlemen, to the Newfoundland, and Cape Briton, in the yere 1536 and in the 28 yere of king Henry the 8.”

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk necktie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. Made exclusively for Canada's History.