Ties that Bind

Trains and railways have been part of Canada for more than a hundred and seventy-five years, with their continuing presence serving as an enduring reminder of the past. Whether it’s the sound of a distant train horn in the night, the picture-postcard sight of a locomotive pulling a string of cars over a long trestle in the mountains, or the experience of being lulled to sleep by the rhythmic motion of steel wheels rolling over track, contact with trains has a way of evoking times past.

The story of Canada is inextricably bound up with trains. Railway development drove Confederation; a promise to build a transcontinental railway brought British Columbia into Canada in 1871; and Prince Edward Island’s rail-building debt pushed it into becoming a province in 1873.

For some, the coming of the railway meant the end of a way of life. First Nations lost their traditional territories, being forced onto reserves to make room for newly arriving settlers. The Métis lost their rights as government troops moved speedily by rail to quash the 1885 uprising.

For others, the railway delivered promise and wealth. Many of us are descended from immigrants whose first memories of Canada are of crossing the country by rail in a no-frills colonist car. Train travel made the breathtaking scenery of the mountains accessible to anyone who could afford a ticket. Rail lines became, in effect, the new Northwest Passage, efficiently bringing goods from west coast ports to the east, and vice versa.

The great age of passenger train travel ended after the Second World War, when automobiles took over. Yet trains continue to hold a fascination for many people today, from hobbyists who set up elaborate train tracks in their basements to volunteers who run the many train museums across the country.

Trains and railways are embedded in our identity as Canadians. In this article we explore just a few of the countless stories that inform our rail history.

From first railway to last spike

The driving of the last spike of Canada’s transcontinental railway can be seen as the completion of a very long journey that began in Lower Canada several decades earlier.

Canada’s first railway — the Champlain and St. Lawrence — opened in 1836 outside of Montreal as a tiny seasonal route — effectively a portage — to connect river traffic. Its first run was completed with help from a team of horses, since it was still early days in the development of engines. Initially the wood-burning locomotive ran only at night, so as not to scare people.

From this small beginning came a frenzy of railway building. The St. Lawrence and Atlantic connected Montreal with Portland, Maine, in 1853; the Great Western linked Niagara Falls to Windsor in Canada West in 1854; the Grand Trunk tied Montreal to the United States at Sarnia in 1860; Prince Edward Island’s costly and meandering rail line reached into every corner of the island by the mid-1880s.

Nervousness about possible American aggression during and after the American Civil War led the Fathers of Confederation to write the publicly owned Intercolonial Railway of Canada — linking linked Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Quebec — into the British North America Act in 1867. And, after promising British Columbia a transportation link to eastern Canada within ten years of that province joining Confederation, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald pushed ahead with building a railway over some of the roughest terrain in the world.

The line was built at great cost. Seventeen thousand labourers came in from China to work at back-breaking labour in dangerous conditions for low pay; about seven hundred died. The material costs were also huge. The federal government gave its private partner, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), $25 million in cash, ten million hectares of prime land, and an exemption from taxes. Even so, Ottawa had to bail out the near-bankrupt CPR more than once and the railway came close to not being finished.

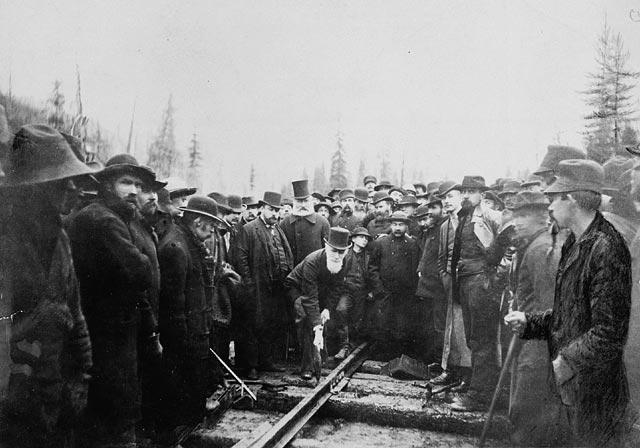

By the time the last spike was driven on November 7, 1885, the sense of exhaustion was evident, and no one seemed in the mood to celebrate. A small party of railroad officials and labourers gathered on a grey drizzly morning at a forlorn spot in the Monashee Mountains of B.C. called Craigellachie. They silently watched CPR director Sir Donald Smith drive a plain iron spike into a regular railway tie — no golden spikes and breaking open champagne bottles, as was the tradition across the border. After railway superintendent Cornelius Van Horne made the briefest of pronouncements — “the work has been done well in every way” — everyone drifted away.

Yet this moment marked the beginning of a new era. Canada was now united from coast to coast.

Moving the troops

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

By the spring of 1885, the Métis living in present-day Saskatchewan had had enough of the federal government’s refusal to address their grievances over their rights to their land, their language, and their culture. As they had done sixteen years earlier in the Red River Settlement under Louis Riel, they rose up in resistance.

In both cases, Ottawa sent in troops. The big difference was that in 1885 there was a railway to transport the army. A journey that took three months in 1870 was completed in less than ten days in 1885. This had huge implications.

Riel had apparently not taken the railway into consideration when he came out of exile in Montana to lead the second uprising. Perhaps he was hoping for a similar outcome as with the earlier event — a settlement negotiated before troops arrived. Those negotiations eventually led to Manitoba’s entry into Confederation, and, while Riel was compelled to flee, no shots were fired after the arrival of Colonel Garnet Wolseley’s army.

The second Riel uprising unfolded very differently. A confrontation led by Métis military leader Gabriel Dumont at Duck Lake left a dozen North-West Mounted Police dead. When word reached Ottawa, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald’s Conservative government turned to the CPR for help. This came at just the right time for the CPR, since it was nearly bankrupt.

In return for its help, Parliament authorized a quick loan to the railway of $500,000, with more to follow. CPR superintendent Cornelius Van Horne would later say that the CPR should dedicate a monument to Riel for saving the railway.

But Riel would not be saved. By mid-April the resistance was over. Riel surrendered and was found guilty of treason. He was hanged on November 16, 1885 — nine days after the completion of the CPR.

A thrilling ride

In the days before strict rail safety rules, a daring pastime for some was to ride on a locomotive’s cowcatcher — a triangular metal frame designed to sweep obstacles out of a train’s path. Lady Agnes Macdonald, wife of Canada’s first prime minister, famously documented her wild ride over the Rocky Mountains during the couple’s cross-country journey over Canada’s newly completed Canadian Pacific Railway in 1886. Despite concerns expressed by railway superintendent John Egan, Lady Agnes — who was weeks away from her fiftieth birthday — had train staff fasten a seat to the front of the locomotive.

Later, in her diary, she described her feelings as the train pulled away at Lake Louise: “I feel a thrill that is very like fear; but it is gone at once, and I can think of nothing but the novelty, the excitement, and the fun of this mad ride in glorious sunshine and intoxicating air, with magnificent mountains before and around me, their lofty peaks smiling down on us, and never a frown on their grand faces!” She rode the cowcatcher quite happily for a thousand kilometres from “summit to sea” while her husband John A. Macdonald remained comfortably seated in their private train car with a rug over his knees and reading material in hand.

It was evidently a welcome break for a woman who was by nature bold and curious about the world but constrained by her role as the “Chief’s” wife. “She was ill at ease as a hostess, and such social duties as became a prime minister’s wife did not come easily to her,” said historian P.B. Waite in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

If photos were taken of her exploit, they are no longer in circulation. But it seems others were similarly moved to take a front seat. During a tour of Canada by the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York in 1901, members of the royal party posed for a picture on the royal train’s cowcatcher at Glacier, British Columbia.

The gentleman train robber

Train robberies are a big part of the folklore of the American Wild West. Jesse James, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and other outlaws gained notoriety for their audacious holdups. In Canada, the railways were generally more secure, but at least one famous American train robber made a big splash when he tried his luck in British Columbia.

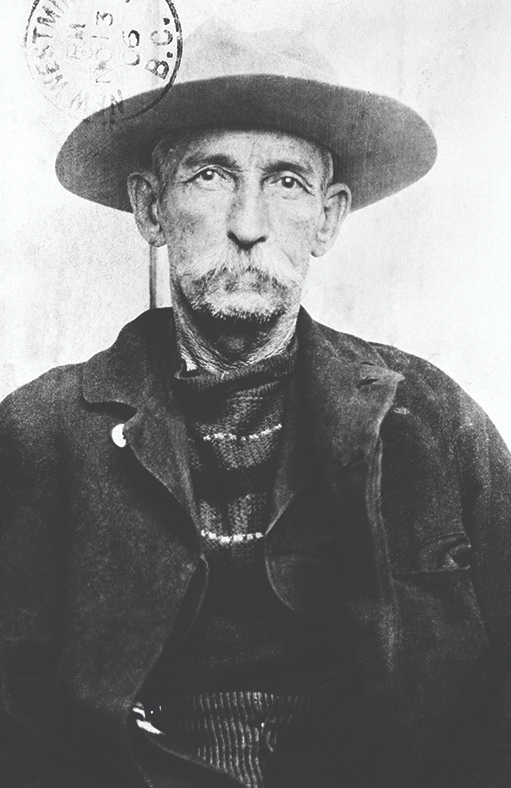

The facts of Bill Miner’s life are not certain, but he had a reputation for unfailing politeness; hence his nickname, the “Gentleman Bandit.” After a robbery, he is said to have always wished his victims a “good day” and is credited with being the first to use the phrase “hands up!” A handsome man, he dressed well and spent lavishly, but he also got caught sometimes and spent much of his adult life in prison.

In 1904, a few years after his release from a California penitentiary, Miner stepped across the border into British Columbia. By then he was about fifty-seven, and, lacking a retirement plan, he continued with his unlawful livelihood. Along with two accomplices, Miner boarded a CPR train near Mission and forced the engineer at gunpoint to halt the train and unhook the baggage and express cars. They took off with at least seven thousand dollars.

Miner lived quietly in B.C. for a couple of years before striking the CPR again, near Kamloops on May 8, 1906. This time things did not go smoothly — Miner’s mask was accidently knocked off, and he and his gang overlooked several packets of banknotes and got away with just fifteen dollars and some liver pills. The North West Mounted Police caught up with them a few days later as they were calmly eating lunch. Miner received a twenty-five-year sentence.

By this time, the British Columbia public was quite taken with Miner’s charm and his boldness in taking on the CPR, an unpopular monopoly at the time. A famous picture taken by Mary Spencer, a photographer on contract with the Vancouver Daily Province, was widely circulated. The Province reported that throngs of admirers were on hand to greet him when he arrived to serve his sentence at New Westminster Penitentiary.

Miner didn’t stay in the B.C. prison long. By 1907, he managed to tunnel his way out and fled to the United States. Once across the border, he continued his life of crime and died in a Georgia jail in 1913.

A circus train tragedy

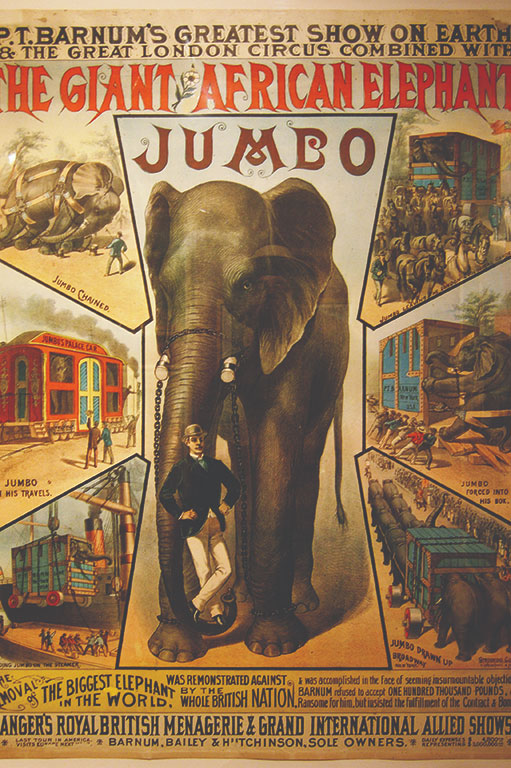

Back in the day, when the circus came to town, it came by rail. Circus trains were a welcome sight as they travelled from town to town, but mishaps occasionally happened. One of the saddest accidents took place on September 15, 1885. On that date, Jumbo, billed by P.T. Barnum as the world’s most famous elephant, performed at a show in St. Thomas, Ontario. As usual, Jumbo was the star attraction, drawing large crowds because of his reputation as an intelligent but gentle animal and his unusually big size.

When the show was over, Jumbo and a tiny elephant, named Tom Thumb, were led along the train tracks on their way to being boarded onto the circus train. At the same time, a freight train came barrelling towards them in the dark. The freight train conductor noticed the animals too late. Seeing the danger, Jumbo reportedly reared up on his hind legs and struck at the locomotive with great force, knocking off the smoke stack and derailing the train. Both elephants were hit. Tom Thumb survived. According to folklore, in his final moments Jumbo reached over to his long-time trainer, Matthew Scott, and drew him in with his trunk.

The accident made headlines around the world. Jumbo had been widely known and loved. He was captured as an orphaned infant in Africa in the early 1860s and was eventually housed in London’s zoological gardens. He gave rides to children, including a young Winston Churchill and the offspring of various European royal families. The London zoo sold him to the Barnum and Bailey Circus but tried unsuccessfully to back out of the deal after vigorous public protests. Jumbo arrived in North America in 1882 and quickly gained a following.

After his death, Jumbo’s legacy lived on. His hide was mounted and toured with the circus for two years. Jumbo has lived on in folklore and was the inspiration for a Walt Disney cartoon. In 1985, the city of St. Thomas erected a life-size statue of Jumbo, which was later include in the city’s North American Railway Hall of Fame.

Canada’s silk road

The completion of Canada’s transcontinental railway in 1885 did more than unite the country; it made the search for the Northwest Passage irrelevant. For centuries, merchants hoped that a navigable Arctic sea-trade route would be found to connect with the wealth of the Orient, but this never panned out. Now, with the port of Vancouver connected to the rest of Canada by rail, a lucrative trade route had opened up. Enter the silk train.

Silk trains ruled the rails between 1887 to the early 1930s. The speedy airtight trains carried bales of raw silk from Japan and had priority over all other rail traffic. The valuable cargo was loaded in Vancouver and rushed to Toronto and then on to the silk mills of the eastern United States. Since raw silk could deteriorate quickly if exposed to heat or moisture, speed was of the essence. The trains travelled at about a mile a minute, which was very fast at the time. The boxcars were shorter than average, the better to take sharp curves at high speed. According to a Vancouver Daily Province report from January 10, 1903, the silk train “makes the regular express time appear as but a snail’s pace.”

Considering all the rush, there were few accidents. The only one on record took place September 21, 1927; a train derailed as it rounded a bend near Hope, British Columbia. No one died, but a number of silk bales tumbled into the fast-flowing Fraser River. According to an article by CN Rail employee Jean-G. Coté in the August 1976 issue of Canadian Rail, bales that had floated downstream continued to be found months afterwards. “Local Indians were paid ten dollars per bale for each one found and turned in, though the value of the contents was by this time questionable.”

Coté also noted that watching a silk train speed by was a thrilling event. He recalled seeing one approach the Edmonton rail yard in 1927: “In two minutes the headlight of the locomotive had expanded from pinpoint size to a solar dimension and the engine blew up a cloud of steam in the wintry twilight, as it roared by … soon only the twin red eyes of its last car marker lights were visible.”

The Depression, the Panama Canal, air travel, and the development of synthetic fibres all contributed to the end of the line for the silk trains. By 1933 these special trains were gone.

Taking in the view

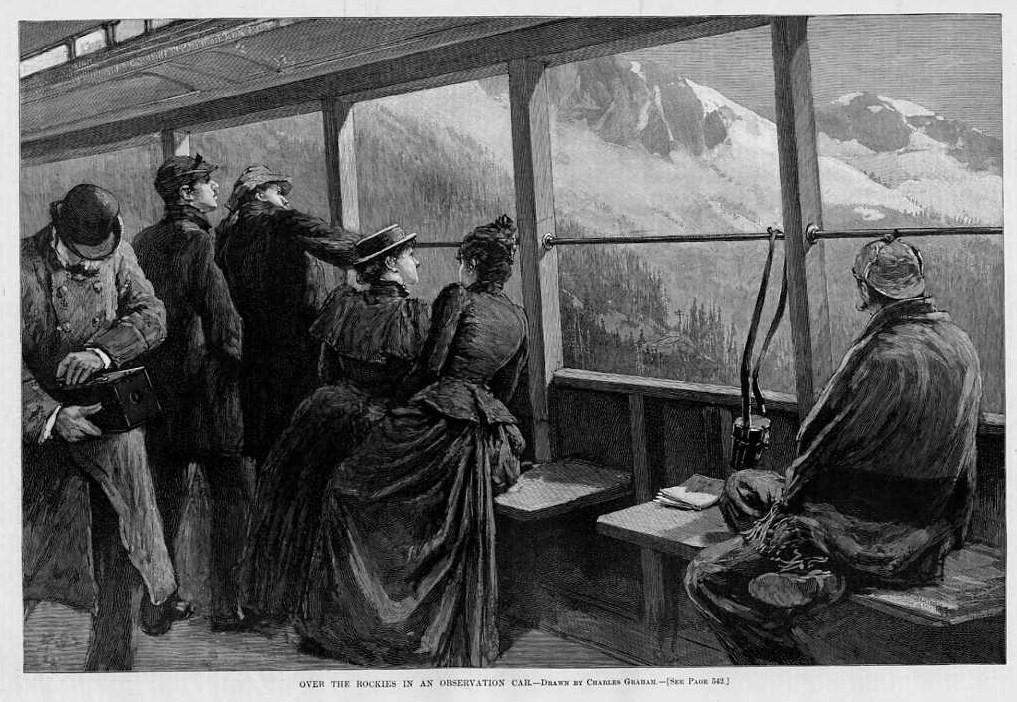

To travel by train through the Canadian Rockies remains one of life’s sublime pleasures. The CPR early on tried various ways of treating its passengers to a full viewing experience while travelling through one of the world’s most majestic mountain ranges. Some early railway observation cars were simply roofless, open-air cars tacked on to the rear of the train — fine for viewing but not so great in rain and cold. Also, cinders from the steam locomotives tended to sting the observers’ eyes.

Near the turn of the century, the railway introduced enclosed observation cars with enlarged windows and cupolas. These provided better visibility but it was still hard to view the tops of the mountains. Next came cars with glass panels in the roof, but these proved extremely hot in summer, while in winter the glass tended to steam over with condensation.

Improvements were gradually made. Rupert Brooke, an English poet who toured the Rocky Mountains by train in 1913 while recovering from a messy romantic breakup, had nothing but praise for the observation car. He wrote: “The Observation-Car is a great invention of the new world. At the end of the train is a compartment with large windows, and a little platform behind it, roofed over, but exposed otherwise to the air. On this platform are sixteen little perches, for which you fight with Americans. Victorious, you crouch on one, and watch the ever-receding panorama behind the train.

“It is an admirable way of viewing scenery. But a day of being perpetually drawn backwards at a great pace through some of the grandest mountains in the world has a queer effect. Like life, it leaves you with a dizzy irritation. For, as in life, you never see the glories till they are past, and then they vanish with incredible rapidity. And if you crane to see the dwindling further peaks, you miss the new splendours.”

Today, the air-conditioned dome cars of Via Rail’s passenger service remain a favourite for rail travellers.

No-frills travel

For most new immigrants who arrived in Canada prior to the 1960s, a long train ride to their eventual destination was among the most vivid of their early experiences. Their first impressions were often of days of travel through a seemingly endless expanses of forest and prairie.

At no time was immigration more brisk than it was during the first decade of the twentieth century, when Canada’s population increased by one third, from 5.3 million to 7.2 million. To handle these massive numbers, CP Rail built more than a thousand colonist cars. The cars, in use from 1886 to the 1940s, offered cheap fares without the frills.

An immigrant interviewed by Barry Broadfoot in The Pioneer Years, 1895-1914, described travelling in the colonist car as a hellish experience: “At night was the worst. The cars were full and babies were crying and I can’t remember any blankets. It seems nobody told anybody to bring bedding, and all our bedding was in our trunks.… I could never stand the sight of a train again. Never.”

Other newcomers didn’t seem to mind. Writing in his diary in 1887, Joseph Eckersley seemed quite happy with the arrangements: “The arrangements for sleeping are contrived by sliding seats. There is a water closet & Stove at each end of the car together with washing stand & bowl. The stove is useful for cooking your food as well as for heating the place.”

The Canadian National Railway and its predecessor, Canadian Northern Railway (1899–1923), also transported large numbers of immigrants. In Canadian Northern Railway and the Men Who Made it Work (1980), author Jack Bradford writes: “Whole families would be confined to one end of a boxcar with their livestock partitioned off with their personal effects in the rest of the car. The noise of these trains and the livestock as they passed through the town and through the necessary switching moves was terrific.”

Secret war train

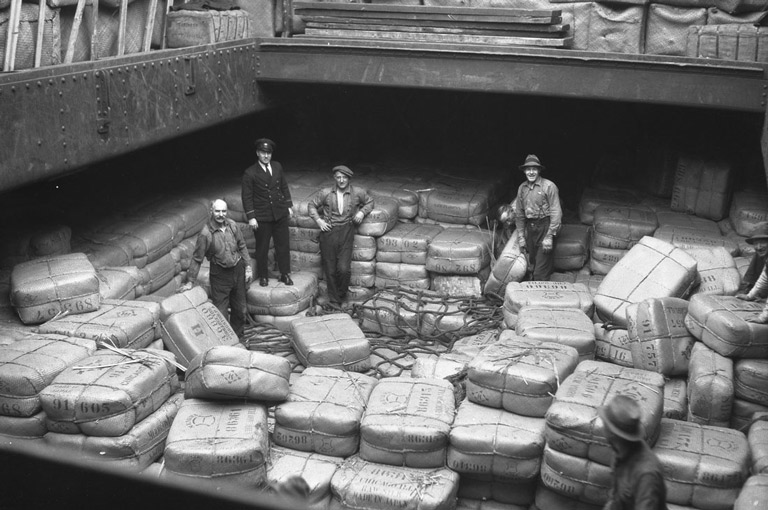

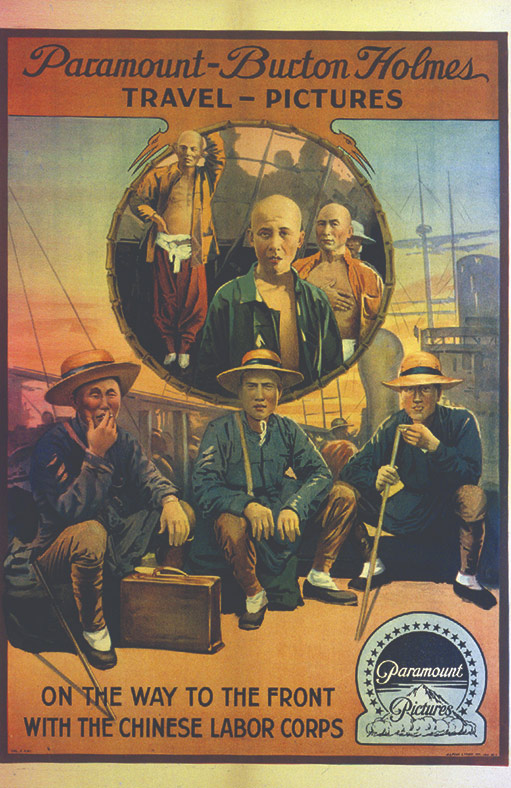

Among the clandestine operations carried out by Canada during the First World War, the transport of more than eighty-four thousand Chinese labourers to the front via sealed trains travelling across Canada ranks as one of the most hush-hush. The Canadian Department of Defence file on the Chinese Labour Corps (CLC) was not declassified until 1985.

The scenario was this: The Allies needed more fighting men at the front. This necessitated freeing regular soldiers from non-combat duties. The solution was to use Chinese labour. Britain and France signed a contract with China in January of 1917 to supply men to work behind the lines in France and Belgium. Canada’s role was to hire the workers and transport them across the Pacific by steamship, overland from Vancouver to Halifax by rail, and then on to Europe by ship.

While travelling across Canada on the CPR — a railway their predecessors from China had helped to build — the labourers were under close guard, and the windows of the train cars were blocked with heavy screens. During stops, the Chinese were not allowed to leave the train, for fear they would escape. Anti-Asian sentiment in Canada was high at the time. In an October-November 1991 article in The Beaver magazine, former guard Donald McKechnie described the precautions as superfluous. “The men gave no indication of being interested in venturing into what would probably have been a hostile environment; and, besides, they were having a good time aboard, and especially enjoyed being fed,” said the article.

Once in Belgium and France, the workers were placed in special camps and performed a variety of duties, such as bricklaying, carpentry, shoemaking, tailoring, and plumbing. Although they were behind the lines, they sustained some casualties from aerial bombing and long-range artillery. And, after the war ended, they were engaged in dangerous cleanup duties that involved handling unexploded ordnance and removing battlefield corpses. At least ten were shot by firing squad, likely for mutiny. In total, about two thousand members of the CLC died in Europe, according to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

The labourers returned to China by the same way they left. Again, sealed CPR trains took them across the continent. On one occasion in March 1919, a riot broke out at the overcrowded William Head quarantine station near Victoria, and two thousand men escaped. Most were apprehended, but an unknown number melted away into Victoria’s Chinatown. By April 1920, the last steamship carrying the CLC had left Canada for China. But it would be at least seven decades before this unusual chapter of Canadian history became public.

Happy holidays

There was a time when rail travel was the fastest, most convenient mode of travel available, a time when trains went almost everywhere, including resorts, beaches, and ski hills. In fact, many of today’s most popular vacation destinations owe their existence to the railways.

Banff, Alberta, is a prime example. Its tourism potential was immediately recognized when three railroad workers stumbled across a series of hot springs in 1883. The springs, combined with the magnificent scenery, inspired the CPR to erect the elegant Banff Springs Hotel in 1888. The Banff Springs was just one of many grand hotels built by the railways.

Some fared better than others when passenger rail use declined. Minaki Lodge, a luxury resort in northwestern Ontario that was completed by the CNR in 1927, was a popular destination until after the Second World War. After that, it fell into steady decline, despite many ownership changes and millions of government dollars spent on renovations, eventually burning to the ground in a spectacular fire in 2003.

For those without the means to stay at a luxury resort, the railways provided affordable day excursions to the beach. Lake Winnipeg, north of the city of Winnipeg, was a particularly popular destination. It all came about when CPR president Willian Whyte, who liked to boat on the lake, decided that a sandy strip of shore on the west side would make a good amusement zone. In 1901, he purchased a thirteen-hectare farm along the shore and extended a rail line to the property. Soon, there was a rail station, amusement rides, a dance hall, concession stands, and other amenities. It cost fifty cents to take train to Winnipeg Beach — a distance of about eighty kilometres — and by 1914 as many as forty thousand people a day were travelling the route in the summer.

Not to be outdone, the rival Canadian Northern Railway (later known as the Canadian National Railway) built a line to the beaches on the east side of Winnipeg, attracting similar numbers of people. As many as fifteen trains a day travelled up and down the Lake Winnipeg shoreline in the 1920s.

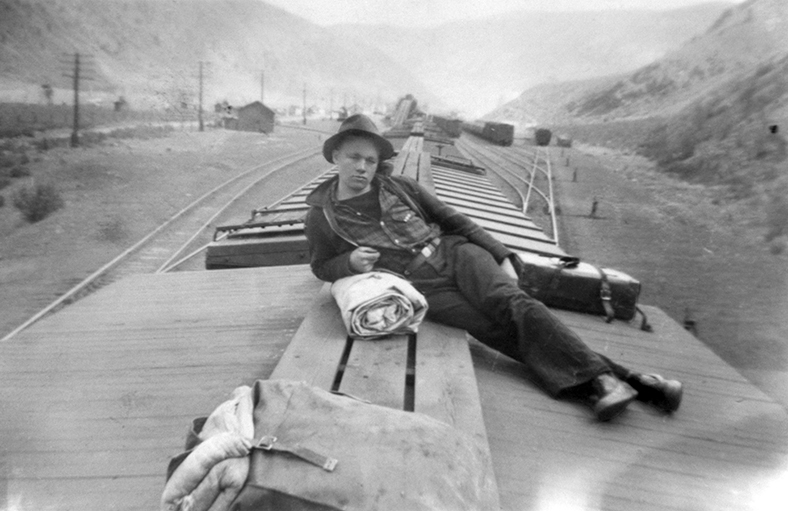

Riding the rails

During the dirty thirties, sneaking onto a boxcar was a cheap, fast way for unemployed people to move across the country in search of work — or to stage a demonstration. In June of 1935, during the height of the Great Depression, more than eight hundred relief camp workers in Vancouver clambered up iron ladders along the sides of an eastbound CPR freight train for the first leg of planned journey to Ottawa. The On-to-Ottawa Trek was set up to protest what organizers called “slave labour” conditions at the relief camps, where indigent men laboured on public works projects for twenty cents a day.

James Kingsbury of the Toronto Daily Star, rode along with the protesters as they clung to the tops of boxcars. He reported that their faces were soon blackened by coal dust and their eyes became red and watery from flying cinders. At the mercy of the elements, they were often soaking wet and shivering from cold. But the highly disciplined group caused no trouble and received a great deal of support, even from police, who initially looked the other way. Kingsbury reported that twenty-four British Columbia provincial police officers “gave the boys a big cheer and a wave of their hands as the train passed the boundary” into Alberta. Many people provided food, shelter, or transportation as the trekkers rolled through their communities.

By the time the hobo army reached Regina, the rail-riding crowd had grown to two thousand. Determined to stop the protest, Prime Minister R.B. Bennett’s government ordered the CPR and the CNR to regard the trekkers as trespassers and to ban them from their trains. Meanwhile, a delegation of trek leaders was allowed to carry on to Ottawa as regular train passengers. But their meeting with Bennett did not go well. Tensions increased as the RCMP moved in to arrest the trekkers and detain them at a special camp. On the July 1, 1935, the Regina Riot broke out after mounted police charged a crowd. One plainclothes officer died, and about 120 protesters were arrested.

Fearing more violence, Saskatchewan Premier James Gardiner stepped in and brokered a deal in which the trekkers would receive free train transportation back to where they had come from. The On-to-Ottawa Trek was over, but few sympathized with Bennett’s harsh tactics. Within months, Bennett’s government was voted out of office.

School trains

If you were a child living in a remote area of northern Ontario between the 1920s and the 1960, you might have attended school in a railcar. Schools on rails operated on a number of routes to provide an education to the children of railway workers, miners, forestry workers, trappers, and other northern residents.

The Northern Ontario Railroad Museum and Heritage Centre in Capreol, Ontario, describes the school on wheels as a joint venture between the Ontario Department of Education and the CN and CP railways. A train would drop the railcar off at a designated siding. Kids would arrive and attend school for about a week. They would then be given enough homework to last them until the next time the car came around.

“They travelled by foot and by canoe and on skis and snowshoes,” says the museum’s website. “One story tells of two young boys aged nine and eleven who travelled twenty miles by dog sled and who then built a small lean-to shelter of pine boughs to stay in overnight. It was minus forty degrees.”

The school car was half classroom and half residence for the teacher — and often for the teacher’s family. Fred Sloman spent thirty-nine years as teacher on a school car that served a 240-kilometre stretch between Capreol and Foleye. Not only did he and his wife, Cela, raise five children in the school car, they became an integral part of the each settlement. They provided basic medical care, offered various kinds of help to new immigrant families and even provided entertainment in the form of movies, bingo, and card nights.

Sloman was inducted as one of the heroes of the Canadian Railway Hall of Fame in 2003. “Northern Ontario in those days was a land of hardships and deprivations, and Sloman diligently shared his knowledge with the locals and made a real difference in their lives,” says the hall of fame’s website.

The school on wheels program ended in 1967.

Centennial train

For those who couldn’t attend Expo 67 in Montreal, a visit to the Confederation train was the next best thing. Considering how central the building of the transcontinental railway was to the birth of Canada as a country, it’s little wonder that the train was one of the most popular features of the 1967 centennial. With its sides dramatically emblazoned with colourful centennial graphics and its locomotive numbered “1967,” the train stopped at more than eighty cities and towns across the country. It featured six coaches filled with multimedia exhibits telling the story of Canada from its prehistoric beginnings to the atomic age.

The train was outfitted with a special horn that played the first four bars of “O Canada.” People lined up for hours to step on board. (Similar tractor-trailor caravans travelled to communities not accessible by rail, attracting comparable crowds.) As Peter H. Aykroyd wrote in The Anniversary Compulsion (1992), the long lineups were not a deterrent. “People didn’t mind. After all the caravan comes to us, doesn’t it? It’s a privilege. Glad to wait.” Moreover, admission was free.

The journey started in Victoria on January 9, 1967. The train arrived on the east coast in October, then doubled back to end its journey in Montreal on December 5. Visitors all experienced what was then cutting-edge technology that allowed them to see, hear, and feel some of the benchmarks of Canada’s history. “The visitor to the train will feel what it was like to take steerage passage to Canada from Europe as so many Canadian immigrants did,” promised its marketing material. “He will be surrounded by the atmosphere experienced by the Canadian soldier in the First World War. He will be taken dramatically through the boom and bust of the twenties and relive the atmosphere of the hungry thirties.”

Not everyone welcomed the train, though. In Montreal, a group of about seventy separatists attacked it, throwing paint on its sides. The protesters denounced the exhibition as propaganda that lied about events such as the deportation of Acadians. At another demonstration, in Quebec City, separatists argued with visitors, calling them traitors to Quebec.

Most Canadians loved the train, though. The Confederation train received more than 2.7 million visitors, and most were quite happy to, as the marketing material stated, “see Canada as you’ve never seen it before.”

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement