The Great Hunger

On a cobblestone quayside in the heart of Dublin six human figures, cast in bronze, trudge alongside the River Liffey. Each is gaunt and emaciated, clothes hanging in rags. One carries a small child, and it is not apparent whether the child is alive or dead. They are harassed by another figure — a dog, its tail between its legs and its ribs showing as it snarls and barks. The forlorn outcasts make their way toward the ships that will take them away from blighted Ireland.

These statues represent more than a million Irish refugees who fled the Great Hunger — in Irish Gaelic, an Gorta Mór — as the Irish famine of 1845 to 1852 is sometimes known. It is argued that the disaster was not truly a famine because, in spite of the starvation that killed a million people, British policy enabled Ireland to continue exporting food.

The statues of Dublin’s Irish famine memorial, simply titled Famine, were created by Irish sculptor Rowan Gillespie and unveiled at a sesquicentennial ceremony in 1997. This year marks the 175th anniversary of what the Irish call Black ’47 — and there’s no doubt that 1847, the worst year of the famine, represents a pivotal year in Irish history.

But 1847 was also a horrific year in Canadian history: Approximately one hundred thousand Irish men, women, and children — all of them hungry, many of them sick with highly contagious diseases — arrived in the colonies of British North America. Cities and towns were overwhelmed by a tidal wave of refugees — in many cases, the Irish immigrants outnumbered the existing population. The famine in Ireland led to a typhus epidemic in Canada. The death rate among the refugees was appalling: about one in six. The pandemic that killed so many Irish immigrants also took a fierce toll on the people we now call front-line workers — the nurses, doctors, nuns, priests, and volunteers who cared for the ailing. Though they occurred nearly two centuries ago, the events of Black ’47 have left an indelible imprint on Ireland and on Canada, linking both countries by strong bonds of genealogy and shared history.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The links between Canada and Ireland go back many generations before the Great Famine — as early as the sixteenth century, when Irish fishermen toiled in the waters off the coast of Newfoundland. In the early nineteenth century, droves of Irish emigrants — at first mostly Protestants, but with an increasing number of Catholics after 1820 — left the island seeking opportunity abroad. By 1830, about thirty thousand people a year were arriving in British North America from the British Isles — two thirds of them from Ireland. By the time of the first Dominion census in 1871, nearly a quarter of Canadians had Irish ethnicity. As the historian David A. Wilson observed, “English-speaking Canada had a significant Irish accent.”

The Irish were leaving an island fractured by sectarian and class strife. After centuries of war and colonization by English and Scottish settlers, the vast majority of the Irish lived in poverty on estates owned by landlords residing in England. The lower classes — including the cottiers who farmed small plots of land and often paid their landlords in labour — were Catholic. The land-owning and merchant classes were Protestant.

The island also had one of the fastest-growing populations in the Western world. Estimated at three million in 1700, by the 1840s the Irish population had reached 8.5 million. But, while Ireland’s population increased, its agricultural productivity did not. With so many of Ireland’s poor living on small plots of land on landlords’ estates, Irish farms produced half the yield of English farms. Economic thinkers debated ways to introduce commercial farming methods to increase production — methods that involved, in part, clearing cottiers off the land. Thomas Malthus, an influential English economist and demographer of the time, predicted that population growth would outstrip food production, leading to famine. Among the ruling classes, some argued that such human calamity was inevitable and would eventually clear the way for economic progress.

What sustained so many Irish people in such poverty? New varieties of potato were being cultivated in the acidic, boggy, and rocky soils of the western counties and in the mountains beyond the fertile valleys. Even these poor soils could yield nearly fifteen tonnes of potatoes per hectare. The crop was nutritious and, combined with cow’s milk, provided a reasonably balanced diet.

Early in the 1840s, the potato became vulnerable to a strange new disease. First, light green spots began to appear on the edges of potato leaves. The spots grew larger and turned black. Soon the plants rotted above the ground, leaving a terrible stench. Even an otherwise healthy-looking potato dug from the soil would turn to black mush in a couple of days.

The potato disease arrived in Belgium in June 1845. By September, the Dublin Evening Post reported that the blight had shown up in Ireland. But, the newspaper assured readers: “We believe that there was never a more abundant Potato Crop in Ireland than there is at present.” Botanists thought the disease was some kind of root rot, exacerbated by that summer’s unusually damp weather. The problem would disappear once the weather changed, they theorized. They were wrong. The disease was Phytophthora infestans, a fungus whose spores could be blown across great distances, and which would return year after year.

The 1845 potato crop rotted in the ground. The crop failed again in the summer of 1846. Food prices rose. Wages fell. Tenant farmers could no longer pay their rents to absentee landlords. The soup kitchens, public-work projects, and work-houses proved insufficient to relieve the growing crisis.

The workhouses, in particular, exacerbated the problems created by the famine. They had been established in the previous century and systematized in 1838 as a way to house and feed the poor. Entire families were brought to these large institutions, where they were separated by gender and given menial jobs such as breaking rocks or picking fibres from ropes to be used for caulking. During the famine, so great was the demand for relief that the destitute wandered the country looking for a workhouse that would take them in. By bringing hundreds of people together in a confined institution, the workhouse system contributed to a new crisis. In January 1847 — even before the fungus returned to destroy the potato crops — several contagious diseases, including typhus, erupted in Ireland. Typhus is a highly transmissible bacterial infection spread by lice and prevalent in crowded, unsanitary conditions, such as workhouses and — as would be tragically revealed — ships.

Patients suffer high fever, headaches, excruciating muscle pain, rashes, vomiting, diarrhea, and delirium. As the disease spreads through the body, it causes inflammation of blood vessels, blood clots, and organ damage. Left untreated it can have a mortality rate of up to sixty per cent.

Advertisement

In the north of Ireland, the Enniskillen Chronicle & Erne Packet reported, “The country districts are in an awful condition; every second house is infected, and every day witnesses some one of the inmates being carried to the grave. In many instances, whole families are discovered dying at the same time, without either food, clothing, or any person to minister to their wants.”

In County Clare, in western Ireland, a public servant observed “women and little children, crowds of whom were to be seen scattered over the turnip fields, like a flock of famished crows, devouring the raw turnips, mothers half naked, shivering in the snow and sleet, uttering exclamations of despair whilst their children were screaming with hunger.”

The combination of starvation and typhus destroyed social cohesion. The Times of London reported on food riots in Dublin, where “a mob consisting of between 40 and 50 persons, many of them boys, commenced an attack on the bakers’ shops.” In some communities in the countryside, survivors could not summon the strength to remove, transport, or bury corpses. Bodies were deposited into shallow, unmarked graves, where animals would dig them up again.

Between 1845 and 1852, approximately a million Irish emigrants — some estimate two million — boarded ships for England, North America, and Australia — anywhere that would take them away from the Great Hunger. Black ’47 saw 150,000 Irish refugees flee to Britain. Another 215,000 sailed for North America; about 90,000 of them headed to the British North American colonies of Canada East (today’s Quebec) and Canada West (today’s Ontario), and another 16,000 to New Brunswick.

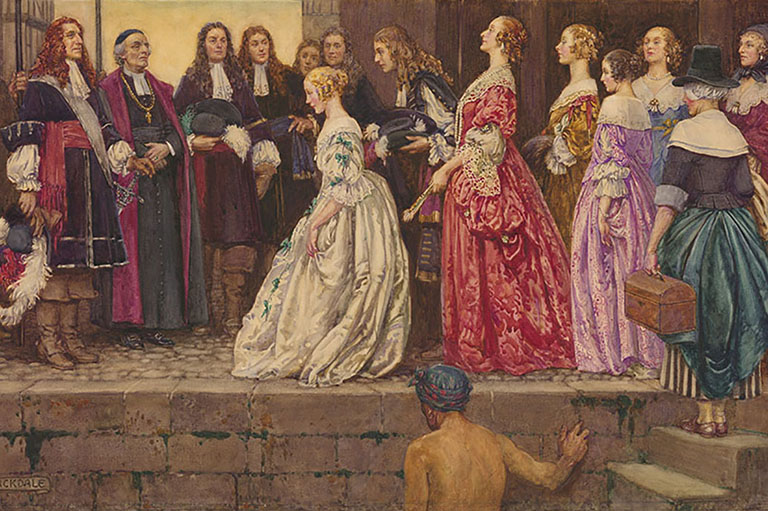

Some landlords saw emigration as an opportunity to clear tenants off their property, consolidate their holdings, and thereby increase the efficiency and productivity of their farms. Amendments to the tax system required landlords to pay according to the number of tenants on their land. It therefore made economic sense to pay for their tenants’ passage out of Ireland. Some landlords added a bonus if the tenants tore down their own cottages before their departure.

A ticket to British North America cost more than three pounds — almost six months’ earnings for an unskilled worker. Fares were often paid by relatives who had already emigrated and established themselves. Meanwhile, changes in American passenger transport regulations raised the fare to ports in the United States such as New York, Boston, and Baltimore to five pounds. At the depth of the Irish famine, British North America thus became the preferred destination for famine refugees. Many intended to continue their journey to the United States, but the tidal wave of refugees would first hit the shores of Canada East and New Brunswick.

For immigrants arriving in the Province of Canada, the first stop was Grosse Île, an island in the St. Lawrence River thirty-four kilometres downstream from Quebec City. During a devastating cholera epidemic in 1832, sheds had been built on the island to create a quarantine station. A system existed that Canadians today, after living through the COVID-19 pandemic, would recognize: Arriving passengers would be quarantined for two weeks — long enough, it was believed, for any disease to be revealed. The sick would be cared for in a hospital until they were healthy enough to continue upriver.

After seeing the first wave of famine victims arriving in Grosse Île in 1846, the medical superintendent, Dr. George M. Douglas, anticipated a tough year for 1847. He took precautions and ordered 50 new beds for the hospital, bringing the total number of beds to 250. His precautions turned out to be not nearly enough.

The first ship to arrive in the 1847 season was the Syria, which docked on May 14 after sailing from Liverpool, England — a common port of departure for Irish emigrants. Of its 245 passengers, nine had died on the voyage. Among those still on board the Syria, at least half were sick with “ship fever” — typhus. Over the following week, forty of them died in hospital on Grosse Île.

Within a week, eight more ships arrived at Grosse Île from Liverpool and from the Irish port cities of Cork, Limerick, and Dublin. Every vessel had typhus cases. The authorities had not considered the possibility of so many cases per ship; nor had they counted on so many ships. By May 30 a line of forty vessels stretched three kilometres along the St. Lawrence River, unable to proceed further without clearing quarantine. A priest at the quarantine station, Father Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau, estimated that, of the thirteen thousand passengers aboard those ships, one thousand were sick. Taschereau described one vessel, the Agnes, as “the most plague-ridden ship of all and in danger of losing everyone on board.” In the end, of the 430 passengers who left Cork aboard the Agnes only 260 survived — a death rate of forty per cent.

From the beginning of May to the end of October 1847, 442 ships arrived at Grosse Île, carrying just over 93,000 immigrants (a further 5,282 would-be immigrants had per-ished during the crossing). While immigration records noted a ship’s port of departure rather than its passengers’ nationalities, the Quebec emigration agent, A.C. Buchanan, judged that more than eighty-five per cent of the immigrants were Irish.

Priests visiting one ship anchored off of Grosse Île described how, in the hold where the Irish resided, they were “up to their ankles in filth. The wretched emigrants crowded together like cattle and corpses remaining long unburied.”

By July, the diarist Robert Whyte described “hundreds ... literally flung on the beach, left amid the mud and stones to crawl on the dry land as they could.”

By summertime, the hospital beds were filled — often with two or three patients to a bed — and the additional patients had to be moved to the quarantine sheds. The sick and dying soon overwhelmed the quarantine sheds and were laid out in the aisles of the church. Tents were erected, but they had been constructed without wooden floors, so patients were deposited on the cold, wet ground. One priest wrote: “Beside each tent lies fermenting waste which nobody has had time to carry away, and inside, in two and sometimes three rows, lie living skeletons; with hardly enough straw on which to stretch out their limbs, men, women and children, pell-mell; and so close together that one could hardly take a step without treading on some part of the breathing mass. Nearly all are suffering from dysentery as well as from fever, and are too weak to drag themselves outdoors, and hence must wallow in their own filth.”

During that plague-ridden season, the Grosse Île quarantine hospital admitted nearly nine thousand ailing passengers, of whom more than three thousand died. Meanwhile, with every building on the island full of typhus patients, the passengers who were deemed healthy had to quarantine on board the fetid ships on which they had spent weeks crossing the Atlantic. More than eight hundred of them perished aboard ship, while anchored in quarantine. The dead from the ships and from the hospital were buried at the Grosse Île cemetery — the largest Great Famine graveyard outside of Ireland.

Similarly, in New Brunswick, 17,000 emigrants arrived at the port of Saint John over the 1847 sailing season, almost all of them Irish. They, too, suffered high death tolls: Moses Perley, the emigration agent, wrote that 2,400 perished, including 823 who died at sea.

The people tasked with processing immigrants or treating the sick stood in grave danger of becoming infected themselves. Nurses were expected to share the accommodations and the food of the sick, and when they fell ill there was no one to care for them. Douglas, the Grosse Île medical super-intendent, offered high wages to female immigrants to serve as nurses, but few took up the offer. He turned to the local jail and released prisoners to work as nurses, but many stole from the dead and the dying.

On board one of the first ships to arrive that year was a Dr. John Benson from Dublin. The forty-five-year-old physician had experience working in Irish fever hospitals and volunteered to help Douglas and the medical staff. He died of typhus within seven days. Four of the hospital doctors died of typhus, and all of the medical officers became sick at some stage. Twenty-two nurses, orderlies, and cooks died, while seventy-six fell ill of typhus. The Catholic and Protestant clergy showed great courage in ministering at Grosse Île, but seven of them also succumbed to typhus.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

In their tens of thousands, the Irish refugees were eventually released from quarantine — in many cases as asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic carriers of the disease. The horrors of Grosse Île were soon repeated in cities and towns further up the St. Lawrence River.

In Quebec City, sheds were constructed for the sick and dying next to the Marine and Emigrant Hospital. They were torn down by an angry mob. By the end of the year, the typhus death toll reached 1,041.

Further upriver, the recently elected mayor of Montreal, John Easton Mills, faced a similar mob. With about fifty thousand residents, his city was the largest in British North America, but the population swelled with the arrival of seventy thousand refugees. Fever sheds were built at Point St. Charles along the St. Lawrence River, close to the Montreal harbour. The mob wanted to tear them down and drive out the immigrants. Mills dissuaded the mob and had another twenty-two sheds built and guarded by soldiers. Mills went on to volunteer as a nurse at the sheds, changing bedding and providing patients with water. He contracted typhus and died that November.

Mills was not alone in his sacrifice for the refugees of Black ’47. In Montreal as elsewhere, the front-line workers risked great danger. Of the forty Grey Nuns in Montreal who ministered to the sick, thirty caught the disease themselves, and seven died. The Sisters of Providence took over nursing duties from the Grey Nuns in June; by the end of September, twenty-seven of them had also died. Among the many clergy who caught the fever were the bishop of Montreal, Ignace Bourget, who survived, and Father Armand-François-Marie de Charbonnel, who also survived and later became the bishop of Toronto. Those who died included the Vicar General of Montreal’s Hôtel-Dieu hospital, M.H. Hudon.

Records indicate that 3,579 refugees died at Point St. Charles. They were buried in unmarked graves along the St. Lawrence River. Twelve years later, some of the human remains were uncovered by a construction crew — some of whose workers were likely survivors of Black ’47. The navvies removed a huge boulder from the river and placed it over the graves with an inscription: “To preserve from desecration the remains of 6000 immigrants who died of ship fever A.D. 1847-8 this stone is erected by the workmen of Messrs. Peto, Brassey and Betts employed in the construction of the Victoria Bridge A.D. 1859.”

It’s unknown how the workers came up with the figure of six thousand dead, as inscribed on the boulder that is known today as the Black Rock. The Montreal Irish Monument Park Foundation is working with Hydro-Québec and the city administration to have the boulder incorporated into a memorial park where visitors can remember both the refugees who perished and the many individuals who, regardless of language, religion, or heritage, provided help and comfort to the sick and dying.

The website of the Montreal Irish Monument Park Foundation describes the city’s response as “one of the greatest humanitarian efforts ever seen in Montreal or Quebec or Canada.” That may be right, but similar acts of courage and dedication were replicated in other communities across British North America.

The Mohawk of Kanesatake, located just west of Montreal, were among those who raised money for famine relief. The Bishop of Quebec sent out a call for French-Canadian families to adopt the orphans left behind by parents who had died. Some six hundred children were taken into French-Canadian homes. In Toronto, the Mirror, a Catholic newspaper, urged citizens to do their part to welcome the refugees and tend to the sick and dying: “Better to die in the performance of duty than to preserve life by the cowardly desertion of the afflicted.”

But, just as with the mobs in Quebec City and in Montreal who wanted to destroy the fever sheds, many others did not welcome the Irish refugees. The Quebec City newspaper Le Canadien described them as “low Irish” who were “naked, malodorous and filthy.” In Toronto, chief emigration agent Anthony Hawke said they were “diseased in body, belonging generally to the lowest class of unskilled labourers — very few of them are fit for farm servants. Added to this they are generally dirty in their habits and unreasonable in their expectations as to wages.” He further complained: “Hitherto such people have been the exceptions to the general character of immigration, but this year they constitute a large majority.”

Through the summer and autumn of 1847, the tidal wave of immigrants — and the typhus they carried — followed the waterways deeper into Canada. In Kingston, in Canada West, 1,400 immigrants died and were buried on the site of what is now the Kingston General Hospital. In Bytown (present-day Ottawa), three thousand refugees arrived — many of them sick and destitute — before the Rideau Canal was closed on August 2 to prevent more from coming.

When considering the impact of a huge influx of sick and impoverished refugees on a relatively smaller established population, perhaps the most dramatic example occurred in the city that is now Canada’s largest metropolis. In 1847, Toronto had a population of just twenty thousand. In the course of Black ’47, it received more than thirty-eight thousand refugees. In August, at the crest of the wave, an average of 450 immigrants a day arrived in Toronto. The “Year of the Irish” left an indelible mark on the city.

The city had been given an early warning of what to expect. In January 1847, Bishop Michael Power, travelling to Ireland to recruit nuns for his diocese, saw first-hand the impact of famine and disease, and the desire of so many to escape to North America. He wrote back to Toronto urging the city to prepare.

A new Emigrant Hospital was planned, but there was no time. The General Hospital at the corner of King and John streets was repurposed for the typhus emergency. In June, the city’s Board of Health appointed thirty-six-year-old Dr. George Robert Grasett as superintendent. He soon realized the need to build fever sheds, as the numbers of sick and dying overwhelmed the hospital. Within a month of taking up his responsibilities, Grasett himself succumbed to typhus. By October of that year, Power, who had returned to Toronto to help provide care and ministry to the Irish immigrants, was also dead of the disease.

Some 1,124 Irish immigrants died in Toronto. Among those who survived, many moved on, some to the United States, others to smaller communities, and still others to the countryside, where it was often hard to find work. Farmers were afraid of contracting the disease from Irish farmhands and were reluctant to travel to typhus-ridden Toronto to sell their produce. Some Irish families were grateful to have escaped famine- and disease-afflicted Ireland to make a new start. In urging others to join him, one Irish immigrant, Daniel McNamara, wrote: “Thank God we have left that miserable country, that we are in a good country now, and our children had good health. I have 3s 9p [three shillings nine pence] a day and steady work, laying out a new road and levelling hills.”

But for others the refugee experience brought overwhelming tragedy. For the Willis family — father, mother, and five children — the first loss came at the outset, when one son fell sick before the ship set sail and had to be left behind in Limerick, Ireland. The family’s eighteen-year-old son and ten-year-old daughter died while crossing the Atlantic Ocean, and their seventeen-year-old daughter was removed to the fever sheds in Grosse Île, where she died. The remaining three Willis family members travelled through Quebec City and Toronto to reach Brantford, in Canada West, where the father and remaining son also died of fever. The story of the Willis family was told in a 2009 Canada-Ireland television co-production, Death or Canada.

Irish immigration to British North America peaked during the famine years, then dwindled over the remainder of the nineteenth century. In the fifteen years follow-ing the end of the Great Hunger, another 114,000 Irish immigrants came to Canada; in the twenty years after that, about 70,000 more arrived. By 1914, only one per cent of immigrants to Canada were Irish. In total, from 1829 to 1914, 661,000 Irish men, women, and children came through the port of Quebec, the main entry point into Canada.

For many years, the famine immigrants of Black ’47 were looked down upon by other Canadians. Within a few generations, however, the descendants of the famine Irish found their place in the multicultural mosaic that would become modern Canada. By 1871, the proportion of Irish (both Protestant and Catholic) in the merchant, white-collar, and artisan classes in Canada matched the proportion of Irish in the country as a whole. According to the 2016 census, 4.6 million Canadians claim Irish heritage — the fourth-largest ethnic group in the country.

When looking at Ireland’s contribution to Canada, there is much to cheer about. Notable members of the Irish diaspora range from Father of Confederation Thomas D’Arcy McGee, to prime ministers Brian Mulroney, Paul Martin, and John Thompson, to the members of the folk band The Irish Rovers. Certainly, Ireland helped to build the foundations of Canadian institutions, from the RCMP (modelled on the Royal Irish Constabulary) to the Irish system of education and the Irish textbooks that were influential in establishing public schools in Canada.

But, while we celebrate Irish culture each St. Patrick’s Day on March 17, it is sometimes easy to forget or to ignore the terrible price paid by so many people in Black ’47 — not just the thousands who died or whose lives were shattered, but also the hardships and prejudices faced by those who had fled starvation by coming to a new land, where detractors characterized them as “low,” “malodorous,” and “unskilled.” These stereotypes, forged in the furnace of one of the great tragedies of the nineteenth century, stuck to the Irish for a long time.

The legacy of the famine Irish is now honoured in the heart of Toronto’s waterfront at Ireland Park. On a wall of Kilkenny stone are inscribed the 675 known names of Irish immigrants who died in the city during Black ’47. As more names are identified, they will be added to the wall.

Rowan Gillespie, who created the statues of gaunt, starving immigrants trudging toward the famine ships along the quays of Dublin, was commissioned to continue the story at the other end of the journey. His work, entitled Arrival, is neither triumphalist nor celebratory; rather, it inspires reflection on the plight of migrant people everywhere and in all times. It depicts five human figures who have made the awful voyage across the Atlantic on the coffin ships. They have quarantined in the hellhole of Grosse Île. They are still haggard, gaunt, and emaciated. A woman lies on the ground, perhaps dying. Alongside a chain-link fence, a man cringes apprehensively. Or is he praying? A youth stares wide-eyed at the harbour’s enormous grain silos. But, in place of the overwhelming despair and desperation of Dublin’s Irish famine memorial, two of the figures — a pregnant woman and a man raising his arms toward the city skyline in awe of what has been achieved — offer the promise of hope for the future.

Disease and Dispair Aboard the Coffin Ships

In 1847, at the height of the Irish famine, more than six thousand emigrants died en route to British North America. The ships that carried the Irish refugees became known as “coffin ships” for their filth, crowded conditions, poor food, rampant typhus, and high death tolls.

The transportation of Irish emigrants relied on a system developed to export Canadian timber to the British Isles. Once the timber was unloaded in Britain, a temporary passenger deck was installed in the ship’s hold to carry people on the return voyage to Canada. With some cost-cutting measures, back-hauling people could be almost as lucrative as hauling timber.

One way to save time and money was not to bother caulking the temporary passenger decks. As a result, these decks were impossible to keep clean when food, waste, and filth fell between the cracks. Another money-making measure involved squeezing more passengers into steer-age than the regulations allowed. Britain’s Passenger Act regulated a sleeping area of six feet by eighteen inches (roughly two metres by half a metre) for each steerage passenger. In practice, four passengers — often strangers — were crammed together in one bed measuring two metres long and two metres wide. Sick passengers lay in their own vomit and excrement, spreading filth and disease to their unfortunate bunkmates.

The windowless holds lacked fresh air. The buckets used for toilets remained in the crowded lower decks until the brief periods when passengers were permitted aloft to remove their waste and cook their provisions. But many refugees lacked food. Although captains enticed clients with promises to supplement the passengers’ provisions, they often over-promised and under-delivered — another way to increase profits.

Stephen de Vere, an aristocratic Irish landlord who shared the travails of his tenants by travelling to Canada with them in steerage, described the conditions on board the barque Birman: “Hundreds of poor people ... huddled together without light, without air, wallowing in filth and breathing a fetid atmosphere, sick in body, dispirited in heart." — Don Cummer

The Miraculous Jeanie Johnston

Docked in Dublin’s River Liffey, across from EPIC, Ireland’s Emigration Museum, is a reconstruction of the three-masted barque Jeanie Johnston. Rather than being a coffin ship, the Jeanie Johnston provided safe passage for some 2,500 Irish emigrants across the North Atlantic.

While many famine ships were decrepit relics of the Napoleonic Wars, the Jeanie Johnston was built in 1847 and made her first voyage in 1848. Unlike the overcrowded coffin ships, she often carried fewer than two hundred passengers. Her owner, William Donovan of Tralee, Ireland, along with Captain James Attridge and his crew, took their responsibility for their passengers very seriously.

Before boarding, passengers underwent a medical inspection by the ship’s physician, Dr. Richard Blennerhassett. Those he diagnosed with typhus were not allowed to travel. On the voyage, the doctor implemented sanitary measures including the regular cleaning of the toilet buckets. He requested that, in suitable weather, the hatches be opened to ventilate the lower decks and urged that passengers be permitted to walk on deck in the fresh air for thirty minutes each day. In addition, the food that emigrants brought onboard was supplemented by ship rations including bread, porridge, tea, and molasses.

Together, these factors produced a miracle: In ten years of crossing the North Atlantic between Tralee and Quebec City, the Jeanie Johnston recorded no fatalities. Some passengers were so grateful for their safe and healthy voyage that they wrote to thank Attridge for saving their lives and bringing them to a land of new opportunity.

In fact, with the birth of an infant on her maiden voyage, the Jeanie Johnston delivered one more passenger to North America than she had boarded in Ireland. The grateful parents christened the infant with the eighteen names of the ship, its officers, and its crew: Nicholas Richard James Thomas William John Gabriel Carls Michael John Alexander Trabaret Archibald Cornelius Hugh Arthur Edward Johnston Reilly.

Today the replica of the Jeanie Johnston is open for guided tours. Among its artifacts is a photo of the now-adult infant passenger as a bartender in Minnesota — his name shortened to Nicholas Johnston Reilly. He and his wife eventually settled in Minneapolis and opened a liquor store. — Don Cummer

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement