The Irish Revolutionary who Became a Canadian Nationalist

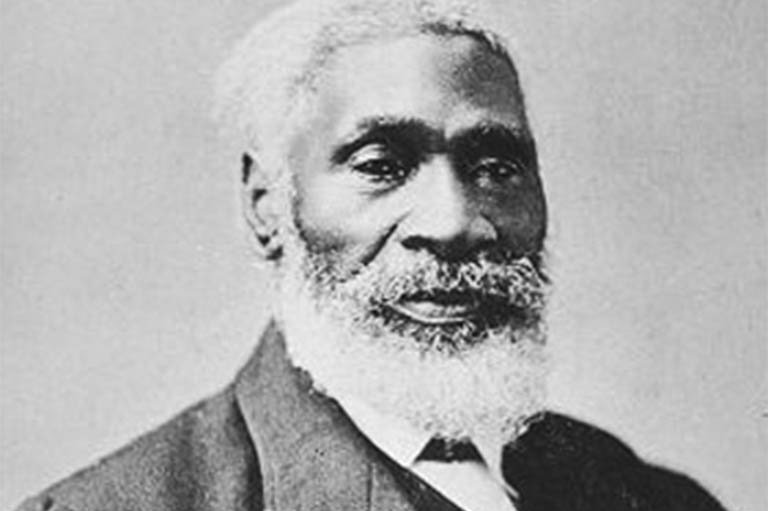

He is remembered best for the worst of reasons. On an April night in 1868, Thomas D’Arcy McGee — journalist, historian, poet, orator, one-time Irish revolutionary turned Canadian Father of Confederation — was assassinated on Sparks Street in downtown Ottawa. Shock waves of grief, anger, and fear pulsed through the country. Six days later, on what would have been his forty-third birthday, some eighty thousand people thronged the streets of Montreal in the largest funeral Canada had ever seen. The tributes were long and lasting: He was a “martyr to the cause of his country,” according to Prime Minister John A. Macdonald. Historian D.C. Harvey later called him “the prophet of Canadian nationality,” while a correspondent wrote to Senator Charles Murphy that McGee was “one of those legendary beings, capable of doing everything and doing everything well.” Canadians were, it seemed, united in admiration and in sorrow.

Not all of them, though. In the backrooms of pubs, in the privacy of their homes, and in safe social circles were those who celebrated, danced, and sang when they read the news. “Here’s long life and prosperity to the man that shot D’Arcy McGee,” toasted a man named Michael Kelly in a Brampton, Ontario, tavern. In Ottawa, a man named Mulvihill “did a step, waving the paper over his head, saying ‘Hell’s flames to your soul, Thomas D’arcy McGee,’” one of the man’s descendants, Nora Daly, later wrote in her memoirs. And in Prescott, Ontario, MLA Mcneil Clarke overheard someone declare that “the shooting of McGee was hard but honest.” The message was clear: For those Irish Canadians who identified with the revolutionary Fenian Brotherhood — which sought to overthrow British rule by violent means — McGee was a traitor to Ireland who had got exactly what he deserved.

Born two hundred years ago, on April 13, 1825, McGee is the only federal Member of Parliament in Canadian history to fall victim to a political assassination. Why did McGee generate such extreme reactions? How did an Irish revolutionary wind up as a Father of Confederation? Who shot him, and for what reason? What was his legacy? The search for answers takes us on a journey across three countries, through revolution, famine, nativism, religious conflict, and political polarization, into the story of one man’s attempt to make sense of the changing world in which he lived and, ultimately, to make it better.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

McGee was born in the town of Carlingford, on the east coast of Ireland. When he was eight, the family moved to Wexford, a stronghold of Irish nationalism that had been at the centre of a bloody and failed rising against English rule in 1798. His father, an Irish nationalist, worked in the customs and excise service; his mother, who died when he was eight years old, inspired him with her love of Irish poetry, legends, and songs.

After spending three years in the United States — where, at the age of nineteen, he became editor of the Boston Pilot, the country’s largest Irish-American newspaper — McGee returned to Ireland in 1845 and joined the nationalist Young Ireland movement, which sought not only to win political freedom but also to promote the language, literature, art, and music of the country.

Finding himself among kindred spirits, McGee articulated his vision for Ireland’s future in a series of newspaper articles and speeches that marked him out as one of the greatest writers and orators of his time. Ireland, he insisted, must have an independent parliament while retaining “the golden link” of the Crown; in this way, Irish interests could be combined with British security requirements, to the benefit of both countries. He advocated a pluralistic form of nationalism, which would encompass and embrace people from all regions, religions, and classes; Ireland was to become a nineteenth-century version of a multicultural society. At the same time, it was essential to protect Irish culture, literature, and music, breaking with English cultural dominance and developing a sense of pride and dignity.

Many years later, his Irish cultural nationalism would assume a Canadian form. “Come!” he would exclaim in 1857 in the New Era, a newspaper he published in Montreal. “Let us construct a national literature for Canada, neither British nor French, nor Yankeeish, but the offspring and heir of the soil, borrowing lessons from all lands, but asserting its title throughout all!” But in 1845 his future in Canada could not have been predicted, and no one would have been more surprised at the turn his life would take than McGee himself. At the time, his energies and emotions were entirely focused on Ireland.

McGee’s passion for building Ireland’s future was heightened by his visits to historic sites and long walks through the countryside. On a three-day pilgrimage to St Patrick’s Purgatory, on an island in Loch Derg, he was deeply moved by the scenic beauty of County Donegal and by the “wild, melodious” hymn sung by “a group of dark-haired, fine-featured young girls.” Within the next five years, most of those young girls would probably be dead.

Beginning in 1846, and lasting until 1851, famine swept across Ireland and wrought terrible consequences for the country. A potato blight destroyed the sole source of food for one-third of Ireland’s population, mainly poor, Catholic tenant farmers, cottiers, and labourers. The response of the government in London was inadequate and inconsistent. “My heart is sick at daily scenes of misery,” McGee said in one of his Young Ireland speeches in 1848. “I have seen human beings driven like foxes to earth themselves in holes and fastnesses; I have heard the voice of mendicancy [beggary] hourly ringing in my ears, until my heart has turned to stone, and my brain to flint, from inability to help them.” Disease, starvation, and mass evictions tore the country apart. By the time it was over, one million people had died; another million emigrated — more than one hundred thousand of them to Canada. “I do, in my soul, believe,” McGee wrote in 1847, “that we are now, at this very hour, in the process of being exterminated as a people.”

Some of the more radical Young Irelanders were gravitating towards revolution as a solution for Ireland’s increasingly dire problems. McGee, along with the majority, remained on the moderate wing of the movement. All this changed, though, when revolution broke out on the streets of Paris in February 1848 and rapidly spread throughout Europe. Suddenly, everything seemed so easy: After a show of strength from the people, their rulers were either fleeing or making concessions. “All over the world,” declared Charles Gavan Duffy, one of the founders of the Young Ireland movement, “from the frozen swamps of Canada, to the rich corn fields of Sicily — in Italy, Denmark, in Prussia, and in glorious France, men are up for their rights.” Surely Ireland, the country that had “suffered more than any other in Europe,” would not allow itself to be left behind.

As the Young Irelanders moved towards revolution, McGee moved with them. In July 1848 he was elected to the revolutionary council that drew up plans for the rising. While his fellow revolutionaries went to the south and west of Ireland to rally their supporters in the countryside, McGee’s mission was to organize Irish revolutionaries in Scotland and bring them over to Ireland: The idea was to seize two or three merchant steamers, put pistols to the heads of their captains, and force them to take a revolutionary army into the northwest of Ireland. There, they would gather support among their countrymen and conduct a guerrilla campaign against the British army, drawing its soldiers away from the main action to the south. “It would be like hitting the enemy in the back of the head,” McGee wrote.

Almost immediately, everything fell apart. In Glasgow McGee learned that he had been recognized and was about to be arrested. His friends there assured him that they would organize the expedition to Ireland, and they advised him to return home to prepare the ground for their landing in County Sligo, on Ireland’s northwest coast. By the time he arrived, however, news came through that the Young Irelanders in the south had been defeated. Upon hearing this, the revolutionaries in Scotland abandoned their plans, and McGee was left alone, with no reinforcements coming. In desperation, he turned to local leaders of agrarian secret societies and tried to persuade them to open up guerrilla operations. After two days of intense debate, they refused on the grounds that there was no chance of success.

With a price on his head and the authorities on his tail, McGee had run out of options. In September he was rowed by a republican sympathizer from the Irish coast to a ship bound for Philadelphia.

Advertisement

Shortly after landing, he wrote a public letter in which he defended Young Ireland’s decision to launch a rising and signed off as “THOMAS D’ARCY McGEE. A Traitor to the British Government.” The British Empire, he now believed, “must be dragged to pieces,” and the best place to start, after Ireland, was Canada. He spent the next eight months spitting fire against all things British, attempting to rekindle the revolutionary flame in Ireland and urging Irish Canadians to avenge the Famine by taking up arms against their rulers. “Either Canada needs a revolution,” he asserted, “or it needs nothing.”

As an exile in the United States, McGee argued that the Young Irelanders should learn from the failure of their rising, build up a secret revolutionary organization, and get it right the next time. But in Ireland, some of his former revolutionary colleagues were drawing very different lessons from the defeat.

One of them, Charles Gavan Duffy, informed McGee in the spring of 1849 that the combined effects of the Famine and military defeat had transformed the situation in Ireland. Revolution, Duffy wrote, was now impossible, and all the wishful thinking in the world could not change that hard reality. If that was the case, the worst thing McGee could do was to lead the people on a path that went nowhere. Instead, he should work for piecemeal, practical reforms that would improve the condition of his countrymen.

Gradually, painfully, McGee absorbed Duffy’s lesson. Establishing his own newspaper, the American Celt, in 1850, and living in New York, Boston, and Buffalo, he repeatedly transmitted the message to his fellow emigrants: Given the power imbalance between Britain and Ireland, revolution was doomed to failure. The way forward was through moral force, not physical force, through gradual reform rather than wholesale revolution. Once McGee had taken that position, there was no going back: Through his writings and his speeches, he set out to defeat the revolutionaries in his midst.

At the same time, McGee was becoming increasingly alienated from what he saw as the American way of life: It was too materialistic, too individualistic, too violent. Meanwhile, his fellow Irish emigrants and exiles, trapped in urban ghettos, were not only experiencing exploitation, degradation, and anti-Catholic prejudice, they were also becoming corrupted beyond recognition.

All of this was happening against the background of an intensifying nativist backlash against immigrants. Attacks on Irish-Catholic neighbourhoods, church burnings, assaults on priests, full-scale riots — all were becoming part of the new reality of the United States. It got worse as the decade wore on, with the growth of the anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant Know-Nothing party, which would win elections in New Jersey, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Indiana, and which looked set to win the presidency. For Irish Catholics, these were terrifying times.

Convinced that American Protestants were fighting an undeclared war against Irish Catholics, and coming to believe that the Protestant emphasis on individual conscience was producing democracy without morality, McGee sought shelter in the Catholic faith. In 1851, after a profound religious experience, he jettisoned his earlier liberalism and resurfaced as an ultra-conservative Catholic. He inhabited a world of absolute moral certainty, in which the Catholic Church stood alone against democratic demagogues, apostate Catholics, persecuting Protestants, radical liberals, and red republicans, all of whom were part of the “Revolution of Antichrist.” It was, to say the least, a truly remarkable transformation.

This meant that many of his former colleagues now viewed him as a traitor. Michael Doheny, who would become a founder of Fenianism, beat him up on the street. But it also meant that McGee began to see Canada in a new light — not as a bastion of the British Empire in North America but as a place where Catholics could breathe easily on the streets, where they could educate their children in their own faith, and where the pace of life was slower, safer, saner. “With us,” he wrote of Americans, “life is a fevered and eager race, with them, a slow and merry procession.”

Critical to his newfound admiration for Canada was the French fact. In the political compromises that had been hammered out over the previous two decades, separate school legislation emerged that enabled Catholics to educate their children according to their own faith. And in Canada East (present-day Quebec) there was nothing like the nativism that he was experiencing in the United States. Not only that, but during several fact-finding tours of British North America he came to see that most Irish immigrants, Catholic and Protestant alike, were living in the countryside, operating their own farms, and doing reasonably well. In 1857, Irish-Catholic community leaders invited him to Montreal to start up a newspaper and run for Parliament.

Four years earlier McGee had visited Niagara Falls, witnessed the Union Jack flying on the Canadian side of the border, and recorded the cataract of rage in his heart at the sight of the “cursed flag” that had been responsible for so many Irish deaths. “My blood leaps wilder than this water/ On seeing thee, thou sign of slaughter,” he wrote in a poem so incendiary that Irish-Canadian author Mary Ann Sadlier later omitted it from her collection of McGee’s poetry. In 1857, things looked very different. “The British flag does indeed fly here,” he wrote, “but it casts no shadow.”

He accepted the invitation and, in December 1857, was elected to the Province of Canada’s legislative assembly.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

And so began his remarkable career in Canada. “I look to the future of my adopted country with hope, though not without anxiety,” he wrote in his most famous speech in support of Confederation. The hope came from a sense of potential, a vision in which people from different regions and with different religions could live together in a society that was inclusive, generous-spirited, and open-minded. The anxiety came from a fear that the “former feuds” of Ireland would take root in Canada and tear the country apart.

McGee was thirty-two years old when he moved to Canada along with his wife, Mary, and his two surviving children, Frasia and Peggy (a daughter and son had died the year before, and another daughter had died earlier in the decade). By this time he had not only shed his earlier anglophobia but also left behind the extreme Catholicism he’d espoused in the United States. He was still a devout Catholic, but he no longer viewed Protestants as his enemies.

The contrast between his dishevelled appearance and his soaring oratory drew many comments, as did his vivacity and sense of humour. He had remarkable intellectual and social stamina, writing a dozen books, hundreds of parliamentary speeches, more than three hundred poems, well over a thousand lectures and innumerable newspaper articles — all before the age of forty-three. And he did this while frequently going on whisky benders, discussing politics and literature well into the early hours of the morning. Efforts of his wife to rein in his drinking were only intermittently successful; living with him cannot have been easy.

He was best known as the Orator of Confederation, the man whose speeches gave poetic voice to the possibilities of the future. Confederation might seem normal and natural now, yet, at the time, it was anything but. There were many regional, religious, ethnic, and linguistic divisions within the country, and the anti-Confederate movement was strong, particularly in Quebec and the Maritimes, as well as in Newfoundland. To push it through took great political skill, some bribery, and powerful arguments — and McGee excelled at the latter.

Less noticed were his practical contributions to the cause. He encouraged Reform Party Leader George Brown to form a coalition government with Conservative John A. Macdonald, achieving a foundation of political stability necessary for negotiations with the other British North American colonies. And he organized a public-relations tour of the Maritime provinces to make the case for Confederation.

McGee did not play a prominent role in the 1864 Quebec Conference that hammered out the details, except in one crucial regard: the establishment of minority educational rights. Support for separate Catholic schools had been a constant factor in his Canadian career, and he had always insisted that Catholics in Canada West (present-day Ontario) should have educational equality with Protestants in Canada East (present-day Quebec). At the Quebec Conference, he got what he wanted. “So far as I know,” he said, “this is the first Constitution ever given to a mixed people, in which the conscientious rights of the minority, are made a subject of formal guarantee.” It was one of his proudest achievements.

Yet McGee’s anxiety about extremist forms of nationalism in Canada did not abate. His fears had originally focused on the ultra-Protestant and anti-Catholic Orange Order, which was going from strength to strength in the mid-nineteenth century. In Canada West, almost all of the elite and a majority of the population were Protestant, the result of immigration by British loyalists after the American Revolution and subsequent waves of English, Scottish, and Irish Protestant settlers through the first half of the nineteenth century. But Irish Catholics also began to arrive around the 1820s to farmstead or to work in lumber camps and canal construction — and their numbers increased as a result of the Famine in the 1840s. Although in many cases Catholics and Protestants lived peacefully side by side, religious tension also existed between the two groups, and this was fanned by militant organizations like the Orange Order.

By the early 1860s, a more immediate threat was emerging — this time from the Catholic side of the religious divide. Founded in 1858, the Fenian Brotherhood was dedicated to raising money, arms, and volunteers to liberate Ireland from British rule. The organization could do this openly in the United States, but in the British North American colonies Fenianism was associated with treason. The brotherhood was gaining ground in Ireland and the United States, and it was making serious inroads into the Irish-Catholic community in Canada. By 1865, one U.S. faction of the brotherhood was planning to attack Britain’s North American empire, and in the following summer it put its plans into practice.

On June 1, 1866, around eight hundred Fenian soldiers in the Irish Republican Army (IRA) crossed the Niagara River into the Niagara Peninsula, planted the Fenian flag, and declared their intention to liberate Canada from the yoke of British oppression. Eight hundred kilometres to the east, the main force of the IRA was gathering in Vermont with the objective of marching on Montreal. Both armies were quickly pushed back, but the threat of further attacks remained.

For McGee, it was essential that Irish-Canadian Catholics distance themselves from the Fenian Brotherhood, even if they sympathized with its goal of freeing Ireland from British rule. If Fenianism took hold in Canada, it would trigger an escalating cycle of conflict in which extremists on both sides of the ethno-religious divide would come to the fore — and in which Irish Catholics, as the minority group, would come off worse. Determined to defeat the movement, he travelled throughout the country giving anti-Fenian speeches to Irish clubs and societies, wrote numerous newspaper articles exposing their clandestine operations in Canada, and supported the suspension of habeas corpus — allowing the government to hold suspects without trial — to counter the threat.

Not surprisingly, those Irish Catholics who either supported or were ambivalent about Fenianism reacted strongly against him. Contrasting his earlier radical Irish nationalism with his current conservatism, they regarded him as a traitor who had sold out his native country for power and prestige, and who by exposing Fenianism in Canada was informing on his fellow countrymen. As sure as God is in heaven, asserted one Matthias D. Phelan in 1865, the Fenians would “wreak retributive vengeance on the parties who threw obstacles in their way. Remember this Kanuck Darky (sic) McGee.” By 1867 he had received so many death threats that he pasted them into a book and drew a skull and crossbones on the cover.

Shortly after 2:00 a.m. on April 7, 1868, McGee, then Member of Parliament for Montreal West, left a late-night sitting of the House of Commons and walked down Sparks Street toward his boarding house. He heard footsteps behind him, quickened his pace, fumbled for his keys, and was shot at close range just as he was opening the door. His murder had all the hallmarks of a hit job by local Fenians, who meted out the traditional punishment for traitors and informers — a bullet in the back of the head.

Police soon received a tipoff pointing them in the direction of an Irish Catholic named Patrick James Whelan. Searching his lodgings, they found Fenian literature, an unsent death threat (to a person unknown), and a revolver that looked like it had recently been fired. The more they investigated, the more the evidence piled up. Reports that Whelan had frequently threatened to kill McGee — and had set out on two occasions to do just that — were compounded by the statement of a witness who saw Whelan making threatening gestures to McGee in Parliament on the night of the assassination. After Whelan’s arrest, a detective and a prisoner who were eavesdropping on his conversations in his cell claimed that he boasted to another inmate about killing McGee.

At the trial, Whelan’s lawyer — John Hillyard Cameron, a Grand Master of the Orange Order — mounted a brilliant defence, challenging every element of the prosecution’s case and arguing that its evidence was either circumstantial or untrustworthy. It wasn’t enough, nor were Whelan’s protestations of innocence. “I never took that man’s blood,” Whelan insisted after the guilty verdict was announced.

But he said something else, shortly before his death sentence was carried out — that he was there when McGee was shot, and that he knew the man who pulled the trigger. And there is an intriguing piece of information that was never brought up in the trial: According to a well-placed informer in the Fenian headquarters in New York, Whelan was not simply a bit player with a grudge against McGee; he was actually one of Canada’s leading Fenians.

Advertisement

We live in increasingly difficult and dangerous times, in which conflicts in other countries have repercussions in Canada — as they did during McGee’s life. Then, there were sometimes-violent tensions between Irish-Catholic nationalists and Irish Protestants; now, we have sometimes-violent tensions between Sikhs and Hindus, Jews and Muslims. Anti-Semitism and Islamophobia are both on the rise. McGee faced down extreme manifestations of nativism, mainly in the United States, but to some extent in Canada as well. For all the twists and turns in his life, one of the constants was his hostility to the abuse of power, whether it came from above or below.

Confronting all of these problems — conflicts imported from abroad, ethno-religious tensions, nativism, and the abuse of power — McGee displayed extraordinary moral courage as he worked towards a form of Canadian national-ism that would be pluralistic, generous-spirited, and broad-minded; one that emphasized the importance of reason, compassion, and kindly feelings, and that strove to find common ground among diverse groups. As we face our own challenges, we may remember this man who also lived through turbulent times and let his voice of moderation echo into our present.

In today’s environment of misinformation and disinformation, it can be hard to know who to believe. At Canada’s History, we tell the true stories of Canada’s diverse past, sharing voices that may have been excluded previously. We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past, highlighting our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages – award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts. Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement