Dreams in the Dust: The Story of Tom Sukanen

There she was, red hull mounted on white keel, rising above the prairie grass of rural Saskatchewan. The thirteen-metre-long Sontiainen never sailed beyond one farmer’s imagination. She was a prairie dust ship, a strange reminder of the madness that ran rampant during the Great Depression.

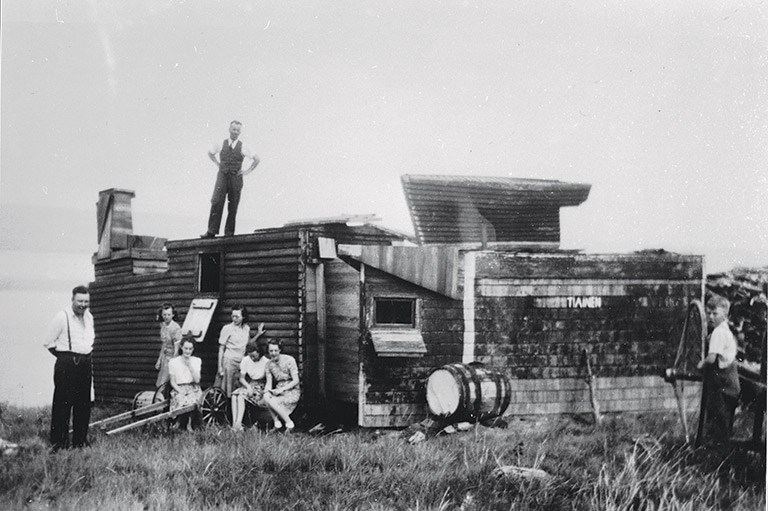

Pictures of the Sontiainen were in our family photograph albums. Dad had seen the ship, had met the huge Finlander, Tom Sukanen, who’d built her. On a cool fall Sunday in 1938, a bunch of farm kids hopped in a truck and drove to see this fantastic thing growing on the prairie.

Dad, just fourteen, the youngest of the group, took photographs of the hull and keel with grandpa’s Kodak box camera.

It was such an unlikely idea, an ocean-going sail and steam ship, built amidst the dust and despair of the dirty thirties, thousands of kilometres from the nearest salt water. The ship took shape near Macrorie, a tiny village located midway between Swift Current and Saskatoon.

Dad never tired of telling us the story. He believed in Sukanen’s dream of sailing the ship across the ocean. Dad believed Sukanen might have done it — if only. Hope dies hard in the West.

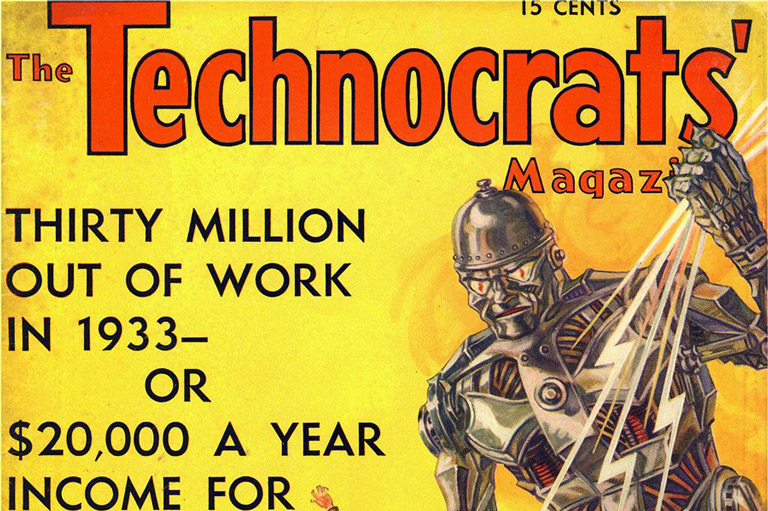

When Dad visited the boat, the Great Depression was drawing to a close and the Prairie provinces were nearing the end of a ten-year drought that had devastated the land.

There had been no decent crops. Even when a little rain fell and wheat came up, grasshoppers quickly devoured it — or the grain was felled by a wheat rust fungus and had to be plowed under.

But mostly there was no rain, only wind. The hot, dry wind blew day and night, carrying off great black clouds of topsoil. My aunt Mabel remembers waking up in the morning and finding the patchwork quilt she was sleeping under had turned one uniform colour — grey.

No one had money. Mom tells a story about my Norwegian grandmother who, after turning her house upside down, still couldn’t find three pennies to buy thread from a travelling salesman. Husbands and sons left home to find jobs.

My dad’s cousin Pat got hurt felling trees up north. No longer able to work, he hopped a freight train south, avoided the railway bulls — as the rail police were called in those days — and slept under a bridge in Saskatoon. He came home hollow-eyed and hungry, just as broke as when he left.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

When all hope ran out, some farmers simply walked out to their barns, slung a piece of rope over a beam, and hanged themselves. Wives were afraid to go looking for them.

In the midst of all this misery was Tom Sukanen. That crazy Finn, they called him.

He had started to build a boat! It would have been funny if things hadn’t been so desperate.

Impoverished farm families were piling everything they owned into wagons and slinking off for greener pastures further west, but this man was spending good money shipping in material from afar for his crazy project — huge flat sheets of steel, stout beams, boxes of nails, bags of bolts.

He’s building an ark, they laughed. It’s going to rain forty days and forty nights, they joked. Where’d this Noah get the money? What a damn fool waste.

The fact that he had decided to build the ship twenty-six kilometres from the nearest body of water — the South Saskatchewan River — did not help. The nearest ocean was at least a thousand kilometres away. Yet he held on to his dream — his crazy, impossible, mad, beautiful dream — to build a steamship and sail her home to Finland.

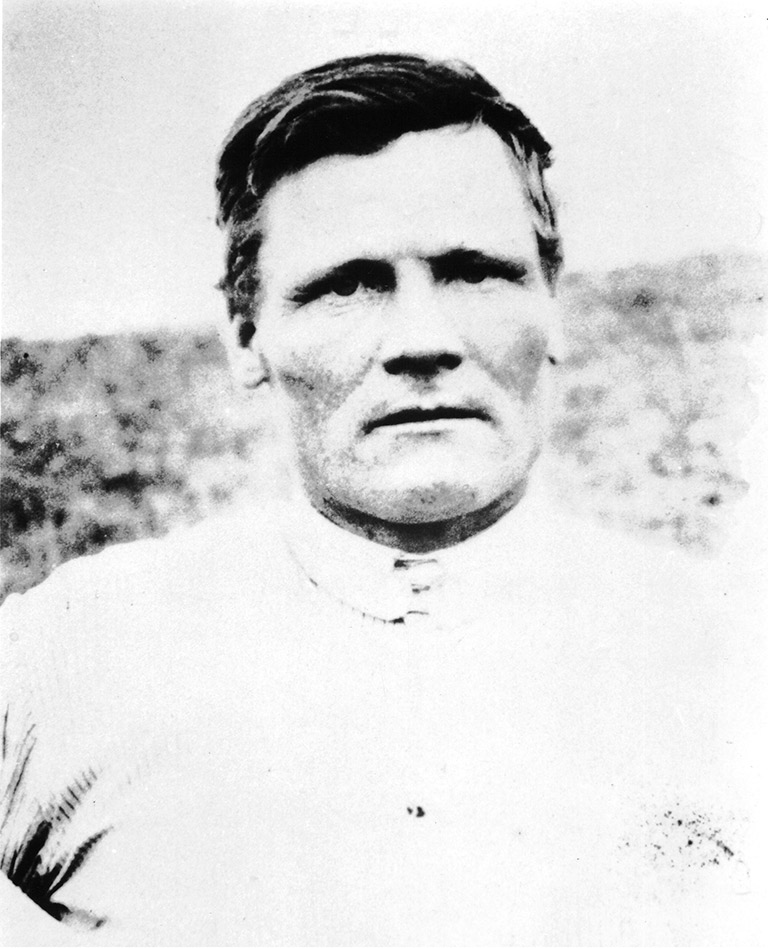

Damianus (Tom) Sukanen was born in 1878 in the village of Kurjenkylä, Finland. He grew to be five feet, ten inches tall. He was barrel-chested, broadshouldered, and possessed immense strength. He trained and worked as a shipwright.

In 1906, he married Sanna Liisa Rintala. Soon after, he sailed to America with thousands of other Finns, leaving behind his pregnant wife. Family members say this was to avoid being drafted into the Russian army, as Finland was controlled by Russia at the time.

A year later, his wife and baby daughter joined him in America. They went to Biwabik in eastern Minnesota, where it’s believed Sukanen had found work in the area’s rich iron ore mines.

According to family members, Sukanen may have been involved in union organizing at the mine. By 1910, the couple had a boy and three girls, including a new baby girl. One night, their house burned down. They all escaped, but one daughter bore scars from her burns for the rest of her life. Some in the family suspected arson, a result of Tom’s union activities.

On March 31, 1911, an article in the Biwabik Times reported that Sukanen’s wife was sent by court order to Duluth for an assessment of her mental condition.

The article was headlined, “Mrs. Sukkanen [sic] Demented. Deserted By Husband, She Is Losing Her Mind,” and stated that “Mrs. Sukkanen has been acting very peculiarly for some time” and had not been taking care of her two-month-old daughter.

The same article also said Tom Sukanen had recently spent ninety days in jail for failing to support his wife and children and had told the court at his trial that he would spend the rest of his life in prison before supporting his family. “He is also said to be mentally unbalanced,” stated the newspaper.

Sukanen abruptly left Biwabik that year and headed to Canada, where his brother Svante farmed in Saskatchewan and where the government was still giving away land.

Incredibly, he walked all the way — about fourteen hundred kilometres. According to family members, he arrived at his brother’s farm near the villages of Macrorie and Birsay with just twenty-eight cents in his pocket. His feet were a mess.

Meanwhile, Sukanen’s wife, known then as Ida, ended up in a mental hospital at Fergus Falls, Minnesota. Relatives say she suffered from depression, was closed up, and wouldn’t speak to anyone in the asylum.

Occasionally she would surprise people by playing the piano. With both parents gone, the children were taken away and put up for adoption; the two oldest girls went to one family while the youngest daughter and son went to another.

After homesteading in Saskatchewan for a while, Sukanen went back to Minnesota for his family. But his wife either refused to come or was too ill. He went to court to get his children back, but the court rejected his request. Sukanen went home alone.

A few years later, Sukanen returned to Biwabik and discovered that his wife had died in the mental hospital in 1914. The story goes that he found his son, Taivo, and tried to bring him back but got caught near the Canada-U.S. border. Again Sukanen returned by himself.

Sukanen may have been bereft, but he was not a loner in those days. On the contrary, he was an active member of his new Canadian community. He went to social gatherings and meetings in the Finnish community hall.

Before the Depression hit, his farm did well. He had good crops, livestock, and, according to local gossip, as much as nine thousand dollars in the bank — a fortune in those days.

He was renowned for his mechanical ability. “His thumb was not in the middle of his palm” is the droll way Finns describe someone like Sukanen, who apparently had the skill to build anything.

But it’s difficult to separate the facts from the myths when it comes to Sukanen’s legendary skills. There still exists a handmade tricycle that he is believed to have built for himself. It’s said he built a small wooden threshing machine, a sewing machine, a wheat-puffing machine, and a violin (that he knew how to play).

But not everyone believed those stories. One summer day, Dad and I went to visit Tom’s nephew Elmer Sukanen and his wife, Helen, on their farm near Lucky Lake, not far from Macrorie. Elmer (now deceased) doubted many of the stories told about his uncle.

More importantly, he didn’t believe that Sukanen was mad, or that the idea of building the boat was crazy or even foolish. It’s the Finns’ way, he said. We might get it into our heads to build something just for the fun of it. The boat was just his uncle’s eccentric, fantastic project. A Finn would understand, Elmer Sukanen insisted.

Local people thought Tom Sukanen was crazy to think he could sail his ship down the South Saskatchewan River. But Sukanen didn’t plan on sailing down the river. That’s why he built his keel and hull in two sections. His plan was to put the deck cabins on a raft, mount his old car engine on the raft with a propeller, and pull the watertight keel and hull on their sides behind him.

The story goes that Sukanen disappeared one summer while planning his ship; he’s said to have travelled by rowboat on the South Saskatchewan to help chart his route to the sea.

His plan was to ride the current downstream past Saskatoon, join the North Saskatchewan River at Prince Albert, follow it east into Manitoba to Cedar Lake and across Lake Winnipeg, then travel northeast down the Nelson River to Hudson Bay. There, Sukanen would bolt the keel, hull, and cabins together on their sides, stuff his keel full of rocks for ballast, and right his ship in the salty water.

Both Elmer Sukanen and a neighbour, Victor Markkula, thought Sukanen intended to install a mast and sail as well. So he would either hoist canvas or fire up his boiler, and sail around the northern tip of Quebec — the Ungava Peninsula — pass Baffin Island on his port side, head east to the tip of Greenland, then on toward Iceland and Scotland, the North Sea, and finally home.

Sukanen must have imagined the scene during those stormy winter nights on the prairie, seeing himself at the helm of his ship, a Finlander arriving home in the port of Helsinki.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

What Sukanen probably didn’t realize — or acknowledge — was that his flotilla would never have made it to Lake Winnipeg; it would have been ripped apart by any number of rapids on the Saskatchewan River, including a 6.4-kilometre stretch of frothing white water at Grand Rapids, Manitoba — now the site of a hydroelectric dam.

If Sukanen had traced that route in his rowboat as the story suggests, it’s doubtful he ever would have started building his boat. Unless, of course he was mad. Or if his ship was one big stick in the eye of a Depression-crazed world.

When Sukanen started building his boat, he went from being admired as a good farmer and mechanical genius to being despised, feared and finally, shunned. After he tore apart his barn, his granaries, and then his house for lumber, he moved into the hull of his ship. He installed a small coalwood stove for cooking and heat and transformed from an eccentric into a recluse. He stopped looking after himself; he lived on handfuls of wheat and rotting horsemeat.

One of the photographs Dad took on the day of his visit in 1938 was of a dead horse under a cowhide on the deck of Tom’s ship. You can see two front hooves, leg bones sticking out from under the cowhide. Dad wondered how he’d managed to haul the thing up there. A dead draft horse, starved or not, must have weighed five hundred kilograms or more. I remember the admiration in Dad’s voice.

Sukanen was famous for his strength as well as for his ingenuity. In the early days of his project, when the sheets of flat steel began to arrive at the railway station in Macrorie, Sukanen loaded them onto his horse-drawn wagon by himself, heaving a single sheet that would take two or three ordinary men to move.

Later, when Sukanen began working on his boilers, he wielded a sawed-off sledgehammer in each hand and pounded the flat sheets day and night until they succumbed and curled into cylindrical steam boilers. The incessant ringing rolled across the countryside, disturbing the neighbours from early morning till late at night.

It took Sukanen about seven years to build the boat. Eventually he stopped farming, but then so had everyone around him.

His tools were rudimentary: Besides the sawed-off sledgehammers, he had an anvil, a forge, a hand drill, a few metal bits, a wood saw, and a hacksaw. With these items, he built a ship. He built the hull and keel separately. The hull was 13.1 metres long and three metres high with a 2.7-metre beam. The keel was 9.1 metres long at the waterline and 2.7 metres deep.

He built his own forge. After he fashioned the boiler, Sukanen made steam cylinders and pistons the same way — with brute force.

He used a hand drill and hacksaw blade with a rag for a handle to cut round holes for pipes in the half-inch metal. He cut gears and sharp-toothed sprockets. He cut up steel rods and heated and hammered them into a chain, one link at a time. When his teeth fell out, he made himself another set out of iron, or so they say.

When the ship was almost ready, Sukanen built two small cabins to be mounted on the deck, fore and aft — one was to be the wheelhouse near the bow; the other his sleeping quarters at the stern. They were clad with corrugated metal and were triangular in shape.

To protect his ship from battering waves and ice, Sukanen wired tin ceiling plates together, nailed them onto his keel, then painted them in horse blood according to a homeland tradition. He named his boat Sontiainen, a Finnish word that means “dung beetle,” perhaps a wry Sukanen joke.

Around 1938, Sukanen started trying to move the hull and keel to the river. The day Dad and the boys came along, the hull and keel were away from Sukanen’s valley farmstead and sitting on the flat prairie.

Sukanen had a set of iron wheels under one end of the hull and a dozen fence posts. But his horses had starved and died one by one during the ship’s building.

Eventually, he was down to one horse and made only a few metres or so a day. In the end, he tried to drag his ship by himself using a winch tied to a post in the ground — a doomed captain at his mast.

By this time Sukanen was in bad shape. His famous strength was gone. He was close to starving. He was miserable, sullen, and filthy, too. The myth said there was nothing Sukanen couldn’t do, but he could not ask for help. He was too proud. None came and none was offered.

Wilf Markkula, son of Victor Markkula, one of Sukanen’s closest neighbours, says his father could have pulled the boat down to the river in a day with his tractor. But Wilf says his dad, perhaps only half jokingly, said he was afraid people would have thought he was crazy, too, if he’d helped. In the end, the hull and keel travelled only 4.8 kilometres.

Finally, in 1939, after many complaints, the RCMP reluctantly stepped in. Constable Bert Fisk drove out with Sukanen’s brother Svante and nephew Elmer. When they found him, he was so weak that he had to be helped to his feet. With tenderness and respect, the constable put him into the front seat of his car and drove him to the mental hospital in North Battleford, Saskatchewan. Sukanen was then sixty-one years old.

While he was in hospital, someone looted and vandalized his ship, stole his tools, and scattered his gear across the prairie. Victor Markkula tried to hide the fact from Sukanen, but one day another visitor let the truth slip out. That’s when Tom’s dream finally ended. He was a broken man when he died at the hospital in 1943. Both husband and wife ended their lives in asylums, twenty-nine years apart.

The story did not die, however. Far from it.

A farmer named Laurence “Moon” Mullin heard about Sukanen and his ship and tracked down the hull and keel. He found them in Markkula’s farmyard, where they had been hauled for safe-keeping — they were being used to store wheat and house chickens.

Dad and I went to visit Mullin and his wife, Hazel, at their home in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. Mullin, an exuberant storyteller, told us how he’d been caught up in the spirit of Sukanen’s dream. He’d retired, sold his farm, and dedicated the rest of his life to salvaging the boat and turning her into a monument.

Mullin, his wife, and others raised money and hired a moving company to haul the hull and keel, donated by the Markkula family, to a rural museum just outside of Moose Jaw. There, they put them together for the first time. Mullen even had Sukanen’s body exhumed and brought down from North Battleford to be reburied beside his ship. They had a commissioning ceremony with bagpipes and speeches.

Sukanen’s story is well-known across the prairies. It’s been the subject of countless newspaper articles, radio and television reports, a chapter in a book about prairie steamboats, a play, a musical, a novel, a documentary, and a screenplay.

In 2009, an art film, Sisu: The Death of Tom Sukanen, written and produced by Chrystene Ells, premiered at the Montreal World Film Festival. And in 2012 a feature film shot in Manitoba, Mad Ship, featured a mad Norwegian farmer and was based loosely on the Sukanen story.

After visiting with the Mullins, Dad and I went to see the Sontiainen at the Sukanen Ship Pioneer Village and Museum not far outside of Moose Jaw. It was a beautiful sunny day. There she was, assembled, hull mounted on keel, bow rising up just the way Sukanen must have dreamed.

The triangular cabins Sukanen had built were long gone. But Mullin and his crew had built some rectangular cabins that looked more like chicken coops and had bolted them to the deck with their square corners hanging out over the gunwales. One good wave would have taken care of them, but I suspect they were designed to accommodate tourists rather than a solitary sailor.

The boilers Sukanen so laboriously made are thought to have disappeared long ago beneath the rising waters of Lake Diefenbaker when the South Saskatchewan River was dammed in the 1950s and 1960s. However, the pistons and cylinders Sukanen built were lying in the grass beside the boat, spray-painted silver.

One thing struck both Dad and me: They were rough and crude. It seemed unlikely that they would have made even one revolution, never mind a transatlantic crossing. Still, we marvelled at the workmanship. Dad was especially happy to be on board this thing that had been such an iconic part of his childhood.

Inside the ship there was a single photograph of Sukanen looking all square-jawed and handsome, the photographer unknown. There were artifacts Mullin had rounded up, such as handmade metal gears, a chain of rough hand-forged links, and a tricycle Elmer Sukanen remembered riding.

Up in the forward cabin, there were the remnants of the chronometer Sukanen is said to have carved. But it, too, seemed an instrument unlikely to keep time accurately enough to chart a position on the tossing North Atlantic.

There remains a gaping hole in the Sukanen legend, a tantalizing, maddening piece of the puzzle that’s missing. No one knows for sure why he felt the need to build a boat to get home to Finland.

Instead of spending money on sheets of steel and lumber, he certainly could have bought a train ticket to Montreal or New York and sailed home on a proper ship.

Elmer Sukanen’s explanations of his uncle’s reasons changed over the years. He told one writer that Tom Sukanen had promised his mother he would be a success in America and that one day he would build a ship and return to Finland to get her.

Some speculate that Sukanen, like so many immigrants, simply wanted to come home in heroic style, proving that he had made it in the New World. But to many people, this dust-covered, flatland Sisyphus had given himself such an impossible task that there can be only one reason for this extraordinary folly — an exquisite madness.

Dad passed away in 2010. I never did ask him if he thought Sukanen was crazy. In those days, in a world half mad with poverty and starvation and gloom, there was a fine line between sanity and the dark side. Besides, Dad often said you had to be crazy to farm in Saskatchewan, anyway.

In the end, it doesn’t matter whether Sukanen was crazy or not. People view his stubbornness, his undisputed ability, and his independence with pride.

For Western Canadians in particular, Sukanen’s ship is a totem of sorts, a symbol of the strength, resilience, work ethic, and, sometimes, madness it took to survive and prosper in this often harsh landscape. To others, there was romance in Sukanen’s outlandish dream.

To Finns, the story of Sukanen is simply the embodiment of their national spirit — in a word: sisu. There is no English equivalent, but it speaks of a tenacious inner strength — guts, will, and perseverance, more than fleeting courage — which sustains Finns as they pursue a heartfelt goal in the face of overwhelming adversity. That’s why Chrystene Ells chose the word as the title of her film about Sukanen.

“What is defeat?” she asks. “Defeat is not failure; it’s when you don’t follow your heart. Sukanen followed his heart.”

Dad would have agreed with that. He had great respect for people like Sukanen, who travelled to the beat of their own drum. As another of his prairie heroes, Tommy Douglas, once said, “Dream no small dreams.”

Perhaps this is why Sukanen continues to fascinate people some seven decades later, why his story earns pride of place among pioneers — those stoic, skilled, resolute men and women who sailed here first, dreamed crazy dreams, and made everything possible.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk bow tie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. This bow tie was inspired by Pierre Berton, inaugural winner of the Governor General's History Award for Popular Media: The Pierre Berton Award, presented by Canada's History Society. Self-tie with adjustments for neck size. Please note: these are not pre-tied.

Made exclusively for Canada's History.