Beautiful Cities

-

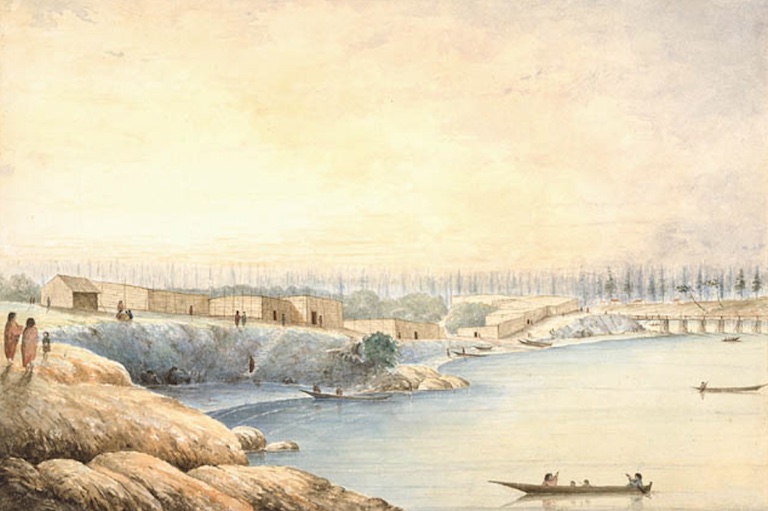

A view of industrial Montreal, 1896.McCord Museum

A view of industrial Montreal, 1896.McCord Museum -

A plan for Mount Royal Park, 1880.McCord Museum

A plan for Mount Royal Park, 1880.McCord Museum -

American landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, 1893.Wikipedia

American landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, 1893.Wikipedia -

The lookout at Mount Royal Park,1916.McCord Museum

The lookout at Mount Royal Park,1916.McCord Museum -

The park’s funicular railway, 1900.McCord Museum

The park’s funicular railway, 1900.McCord Museum -

A calèche and pedestrians at Mount Royal Park, 1936.McCord Museum

A calèche and pedestrians at Mount Royal Park, 1936.McCord Museum -

A 1911 map of Stanley Park, Vancouver.City of Vancouver Archives

A 1911 map of Stanley Park, Vancouver.City of Vancouver Archives -

Workers clear a midden - a deposit of shells - to make way for a road through Stanley Park, 1888.City of Vancouver Archives

Workers clear a midden - a deposit of shells - to make way for a road through Stanley Park, 1888.City of Vancouver Archives -

An aerial view of Vancouver, with heavily treed Stanley Park surrounded by water, 1931City of Vancouver Archives

An aerial view of Vancouver, with heavily treed Stanley Park surrounded by water, 1931City of Vancouver Archives -

A man stands under the entrance arch of Stanley Park, circa 1890s.City of Vancouver Archives

A man stands under the entrance arch of Stanley Park, circa 1890s.City of Vancouver Archives -

Old squatters' shacks at Stanley Park, early twentieth-century.City of Vancouver Archives

Old squatters' shacks at Stanley Park, early twentieth-century.City of Vancouver Archives -

A 1928 map of Hamilton, with Cootes Paradise in the upper right.Royal Botanical Gardens

A 1928 map of Hamilton, with Cootes Paradise in the upper right.Royal Botanical Gardens -

An aerial view of the Desjardins Canal at Cootes Paradise, Hamilton.Royal Botanical Gardens.

An aerial view of the Desjardins Canal at Cootes Paradise, Hamilton.Royal Botanical Gardens. -

The rock garden at the Royal Botanical Gardens, circa 1930s.Royal Botanical Gardens

The rock garden at the Royal Botanical Gardens, circa 1930s.Royal Botanical Gardens -

Sunday traffic on the Queen Elizabeth Way at Jordan Harbour near St. Catharines, Ontario, 1954.Royal Botanical Gardens

Sunday traffic on the Queen Elizabeth Way at Jordan Harbour near St. Catharines, Ontario, 1954.Royal Botanical Gardens -

Thomas Baker McQuesten.Whitehern Historic House and Garden.

Thomas Baker McQuesten.Whitehern Historic House and Garden.

On November 10, 1862, Major Alexander Stevenson, a Montreal city councillor and part-time militia commander, recruited the Montreal Field Battery to help him drag artillery guns up the snow-laden slopes of Mount Royal. After a difficult climb, they reached the summit, where they fired off about a hundred rounds — and alarmed city dwellers below. “The general opinion in the city was that the Fenians had made a lodgement on the mountain,” relates an 1898 history of the field battery.

Stevenson was not trying to start a war. Rather, he was taking the occasion to call for Mount Royal — then a densely forested presence in the countryside held by private landowners — to be made into a public park. He repeated the action the following year. The booming salvos — and the fact that a landowner had cut down a swath of trees on the mountain for firewood, making for an unsightly view — eventually wore down opposition to Stevenson’s idea.

“Give us a noble park on the top of Mount Royal, from whose summit a succession of the most beautiful landscapes can be seen and where the commons may go with their families to breathe the fresh air,” uttered one appeal by a columnist in the Montreal Gazette in 1867. Two years later, the city began setting aside money for the park.

Like other cities in Canada and elsewhere, industrialized Montreal in the 1860s was no Shangri-La. Residents of Canada’s congested rail and factory hub lived with the distinctive smell of industrial pollution, merged with the stench of decaying animal carcasses, horse manure, and open drains. The streets rang with the bustle and din of unceasing industry. For the poorly paid workers who toiled long hours in the dusty factories they lived next to, there was little respite from the gritty reality of their bleak urban life.

Those with money — the merchants and industrialists who had made their fortunes from the city’s economic activity — had a generation earlier vacated the industrial area for more pleasant surroundings at the foot of Mount Royal. This largely Anglo Protestant enclave built its mansions, estates, and gardens on former apple orchards on the plateau. However, the mountain itself was considered too steep and inaccessible for recreation. To get around that problem, the city in 1874 hired Frederick Law Olmsted, the creator of New York City’s Central Park.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Olmsted was an American landscape architect who had taken his country’s cities by storm with an innovative approach to the planning of urban green spaces. By the end of the century, his ideas had grown into a phenomenon across North America known as the City Beautiful movement, itself a precursor to modern urban planning.

“Charming natural scenery,” Olmsted wrote in his 1881 book, Mount Royal, Montreal, “acts in a more directly remedial way to enable men to better resist the harmful influences of ordinary town life, and recover what they lose from them. It is thus, in medical phrase, a prophylactic and therapeutic agent of vital value … and to the mass of the people it is practically available only through such means as are provided through parks.”

Olmsted’s ideas took hold in a few Canadian cities, such as Montreal and Vancouver, in the later nineteenth century. By the time Hamilton came on board in the 1920s, the City Beautiful movement had broadened into professional city planning and the beautification of the entire urban streetscape.

However, according to Sean Kheraj, an environmental historian, grand signature parks and protected green spaces were not originally conceived with nature preservation in mind. Kheraj, an associate professor at York University and author of Inventing Stanley Park: An Environmental History, says the wealthy men who often sat on local parks boards and drove the construction of urban parkland fully expected that these would help their cities attract business investors and tourists. They also saw the opportunity to make money from the increased value of land in the vicinity of these parks.

That explains a preference among the early park boosters in the Victorian period for a pristine display of nature that was clean, orderly, and bereft of permanent residents. No concept existed then of people living in public parks and serving as their stewards.

In Montreal, Olmsted sympathized with those who feared the park would attract vandals and other troublemakers. “I advise you not to allow the mountain to be in all parts left open to be wandered over and used at will at all times by all comers. You cannot afford the force of police which if you will do so, will be necessary to the protection of its finer elements of value,” Olmsted wrote in Mount Royal, Montreal. He recommended family friendly amenities, such as toilets, picnic shelters, and hot water for making tea.

“Make it an easy custom to fall into, by all classes, even your poorest workingman, to come here by families, once or twice a week, late in the day, during the hot season, to take their evening meal,” Olmsted continued, adding: “No men are reckless in their conduct in a place in which good women and children seem to be at home.”

While Olmsted and other park boosters seemed to be advocating for the working class, in reality few common folk from Griffintown and other lower-class districts could afford a horse-driven carriage ride to Mount Royal — and it was a long way to walk.

The park officially opened in 1876. Roads and walking paths were built on the upper mountain plateau, which offered a spectacular view of Montreal. Later, the city built a funicular railway for fast access to the summit. The railway, which operated from 1884 to 1918, was strongly opposed by Olmsted. The American designer believed that park-goers should stroll up the mountain at a leisurely, contemplative pace in order to fully experience its beauty and serenity.

On the other side of the country, Vancouver was also making an effort to establish a signature urban park. On a sunny September 27, 1888, crowds rushed to be first through the gates of newly opened Stanley Park. The city was then just two years old and had a population of just over a thousand people. The four-hundred-hectare park might have seemed large for such a small city, but Vancouver’s boosters dreamed big and modelled their idea for a park on the examples of New York’s Central Park and San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. As one British Columbia provincial official enthused on opening day, Stanley Park “laid the foundations on what promises to be the greatest city on the North Pacific.”

The procession of visitors had a good view of the mountains and the ocean on opening day, the Daily News-Advertiser told its readers. But it failed to mention whether they had noticed the homes of the people — Indigenous and Chinese — who were still living in the park, which was federal Crown land that had been transferred to the city. Not long after the opening, Vancouver park authorities used city health regulations to eject the Chinese families and to burn down their homes.

Meanwhile, Indigenous people had lived in the area for as long as three thousand years, and one village, Chaythoos, was still standing. After the park’s official opening, however, the village was demolished: “The city built the park road through the village and had to remove fencing and other structures as part of the construction process,” said Kheraj.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

While most Indigenous residents were relocated, a few stayed behind at Brockton Point. Park authorities took a more gingerly approach to removing them, concerned that the remaining families would succeed in claiming squatters rights — a situation that could have resulted in the families’ land being sold to private business interests.

Eviction proceedings were not launched until the 1920s. The resulting court case went all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada. Since the families had no written documents proving continuous residence, and the court ruled their oral history to be unsatisfactory, the Indigenous residents lost their case. However, some were allowed to stay, and it was not until the 1950s that Stanley Park was finally emptied of inhabitants.

Unlike Mount Royal, Stanley Park did not benefit from the vision of a landscape designer. This task was left up to Vancouver’s Park Board and its employees. In one notorious case of re-engineering, members of the local gun club were given permission every Saturday morning starting in 1910 to shoot crows, because they were perceived as predators. This was a controversial practice even at that time, and it continued until 1961.

The park’s first visitors would probably have spotted many spindly and dead trees — the result of insect infestation. This did not conform to an urban public’s expectations of a typical Pacific coastal forest. To solve the problem, the Parks Board consulted James Malcolm Swaine, a federal Department of Agriculture scientist who specialized in the application of chemical sprays to battle insect pests.

A Cornell University graduate in entomology, Swaine arrived following a major insect and fungus attack in 1913 on Stanley Park’s coniferous trees. The western hemlock was defoliated by the looper moth. Another insect, the gall aphid, attacked the Sitka spruce. While the spruce trees survived, their needles changed from green to rusty brown and looked ragged. Both species of tree were removed and replaced by hardy Douglas fir trees, which were immune to infestation.

By the 1940s, Stanley Park had become a thick and lush West Coast display of Douglas firs. “It is [Swaine’s] ideas that absolutely shaped the vision of [Stanley Park] that we see today,” said Kheraj.

In southern Ontario, Hamilton’s conversion to a greener city came late, and much of it was driven by one man — Thomas McQuesten. By the time McQuesten was first elected to municipal council in 1913, Hamilton was the largest industrialized city in Canada. But park and recreational space was limited, as new industries and residential suburbs gobbled up scarce land from the top of the Niagara Escarpment to the shore of Lake Ontario.

Much of Hamilton Harbour was heavily polluted from industrial waste generated by lakefront factories, including the large steelmakers. Their employees lived nearby in the northern and eastern ends of the city.

“There was an emergence of the importance of parks in Hamilton as part of the identity, that it was an industrial city but [did not have to be] a dirty industrial city.” said McMaster University historian Ken Cruikshank, co-author of The People and the Bay: A Social and Environmental History of Hamilton Harbour. “It could be similar to Birmingham [in England] but not all of the bad things that one associates with Birmingham.”

Born in June 1882, McQuesten grew up with five other siblings in genteel poverty at the stately house of Whitehern in Hamilton. They were raised by a strict Presbyterian mother whose husband had squandered the family fortune and then died from overdosing on sleeping medication. His mother made clear to McQuesten that it was his duty to restore the family name and fortune. Her influence also drove him to seek social reform through city planning and beautification. Gardens and beautiful surroundings were seen to be morally uplifting. He had no talent for design, but he was able to collaborate with talented city planners, landscapers, architects, artists, and gardeners to design various parks, playgrounds, gardens, roads, and bridges in Hamilton and the Niagara region.

As a member of Hamilton’s Board of Parks Management from 1922 to 1948, McQuesten actively pursued vacant properties that could be transformed into parks. A fortuitous settlement with a developer in tax arrears in 1927 resulted in the acquisition of sensitive properties in the Westdale ravine and adjacent wetlands known as Cootes Paradise. This 991-hectare area was placed under the management of the Royal Botanical Gardens (RBG) and became the base for Canada’s largest protected nature sanctuary of plants, birds, and animals. By 1932, “Steeltown” had the largest acreage of developed parkland and playgrounds of any Canadian city.

Hamilton’s green space attracted a diverse group of people, including those who were not desirable by middle-class standards. During a housing shortage following the First World War, desperate people began squatting in boathouses and shacks on public or railway land in the harbour’s northwest corner. These inhabitants went hunting and fishing for food in Cootes Paradise. McQuesten held little sympathy for them and viewed their makeshift community as unruly. Eventually, the squatters were evicted during the Great Depression. Some of the displaced were compensated with small amounts of money and then hired for the 1929–31 construction of the RBG’s Rock Garden.

McQuesten’s greening influence was felt beyond Hamilton. Elected to the Ontario legislature in 1934, he influenced the replanting of trees on the Niagara Escarpment, the restoration of War of 1812 forts in Niagara and eastern Ontario, and the system of parks and gardens in the Niagara region.

As provincial minister of highways in the 1930s, he also tried to make the drive along Canada’s first superhighway — connecting Toronto and Niagara along the shore of Lake Ontario — a pleasurable and aesthetic experience. The new road was lined with fruit farms and newly planted pine and spruce trees to form a parkway originally known as the Middle Road. Renamed the Queen Elizabeth Way in 1939, the highway’s increased traffic led to its inevitable widening and to the complete undoing of McQuesten’s original vision.

A guarded personality, McQuesten underplayed his role in all of these projects. “I have often said that we have to do good by stealth in this world,” he once stated.

Today, we are fortunate in being able to appreciate the work McQuesten and others carried out in their efforts to beautify Canada’s cities.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk necktie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. Made exclusively for Canada's History.