Sir Wilfrid Laurier and Canada's Jews

To the Jews of Europe, Canada represented endless possibilities for the future. For some, it was a refuge from the pogroms of Eastern Europe; for others, the possible site of an autonomous homeland in the West.

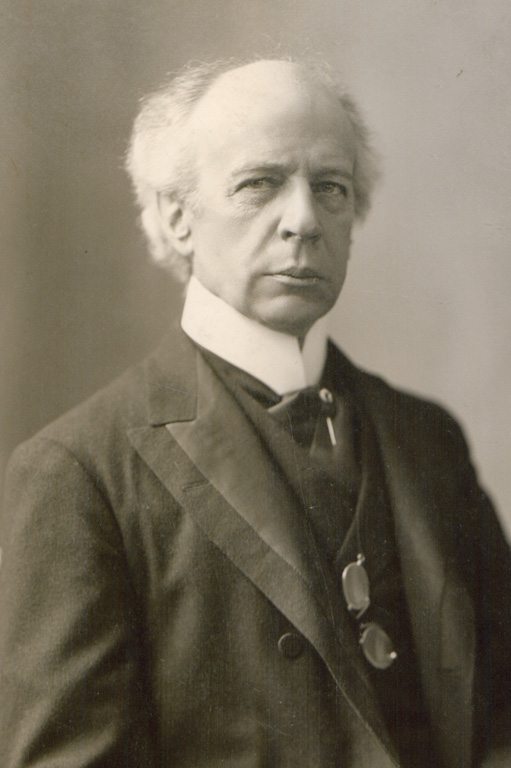

Canada’s seventh prime minister had his own vision of “one great united people,” with no room for separate colonies.

But in 1906 Canada’s Jews seized on a supposed statement that Laurier had indeed promised such a settlement — a statement that has been the subject of speculation for more than ninety years.

In the annals of Canadian Jewish history, it is well known that Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier is alleged to have promised part of Manitoba to the Jews as a place where they might be granted “a measure of self-government,” with their own bylaws, substituting Saturday for Sunday as the day of rest.

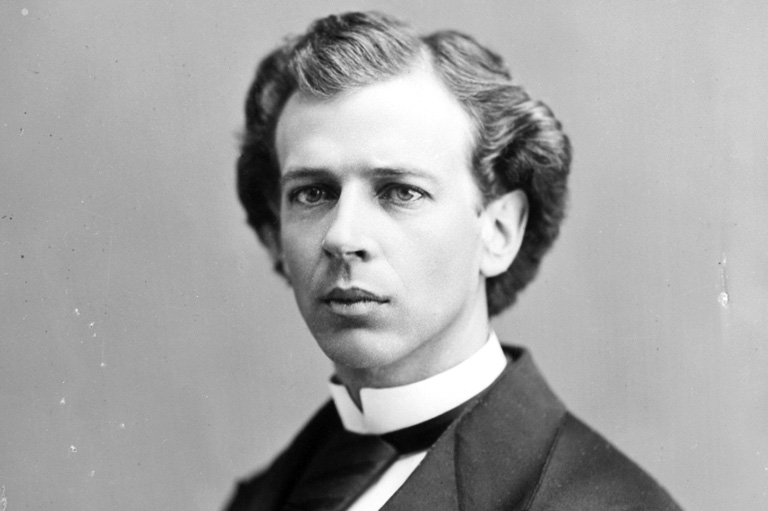

Laurier supposedly made this offer to Herman Landau while visiting London in 1897 for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. Landau, a London Jewish financier and philanthropist, claimed to have had an interview with the Canadian prime minister on the question of Jewish settlement in Canada. But this alleged exchange was only disclosed nine years later in a lecture entitled “Canada and the Jews,” delivered by Landau to the Hampstead and St. John’s Wood Jewish Literary Society.

News of the lecture was reported in the London Jewish Chronicle, January 19, 1906 and reprinted in The Jewish Times of Montreal, February 9, 1906. (The Jewish Times, founded in late 1897 and published biweekly in English, was the first Jewish newspaper in Canada.) The report aroused some excitement in Canada’s Jewish community, for not only did it contradict stated immigration policy, it encouraged the hope held by some Jews for a culturally autonomous Jewish territory.

So who was Herman Landau? And why would he make such a statement publicly?

Landau was best known for his support of the East London Jewish Sheltering Home from 1885. His first known connection with Canada dates back to 1886, when he served as an agent for the Canadian Pacific Railway. Through this connection, he was able to send a group of young Russian Jews to take up land at Wapella, Saskatchewan.

Landau likely made his 1906 statement about Laurier’s offer because a Jewish territorialist organization was then actively seeking a location in any county where Jews might establish an autonomous settlement (as distinct from the Zionist goal of a Jewish homeland only in Palestine).

In his lecture Landau also asserted that he was a friend of Baron Maurice de Hirsch, the European banker, railway builder, and philanthropist who began to assist in the resettlement of Jews from the Russian Empire after anti-Jewish pogroms intensified in that country following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1880.

In 1887, when Lucien, the only child of Baron de Hirsch, died of pneumonia at age thirty-one, the Baron reportedly commented in response to a letter of condolence: “My son I have lost, but not my heir; humanity is my heir.” In his lecture, Herman Landau stated that it was he who, on visiting the bereaved parents in Paris after the death of their son, had suggested they could “adopt all Israel as their children by founding colonies in Canada [to] rescue a great number of Jews from ... persecution ... at the hands of the autocratic Government of Russia.”

Landau claimed the Baron wrote to him shortly after, approving of this scheme and asking Landau if he could find a “devoted, self-sacrificing committee” to carry it out. In fact, before he started such an organization, Baron de Hirsch had directed his philanthropic endeavours to support the work of the Alliance Israelite Universelle in Paris.

And it was a representative of the Alliance who wrote to the Anglo-Jewish Association (not to Landau) on behalf of the Baron to inquire about the possibility of a Jewish farm colony in Canada. Moreover, the name of Herman Landau appears nowhere in any biographical works on the Baron, nor in the records of the Jewish Colonization Association (JCA), which the Baron founded in 1891 for the purpose of resettling Eastern European Jews in places where they could engage in agricultural or other constructive pursuits.

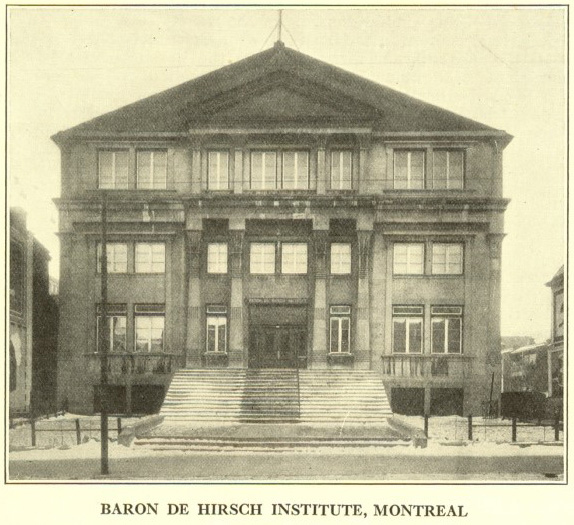

The same year that the JCA was founded, Montreal’s Hebrew Benevolent Society (HBS) received a contribution of $20,000 from Baron de Hirsch to support its welfare services. The building purchased to serve as an immigrant shelter and welfare headquarters became known as the Baron de Hirsch Institute (BHI).

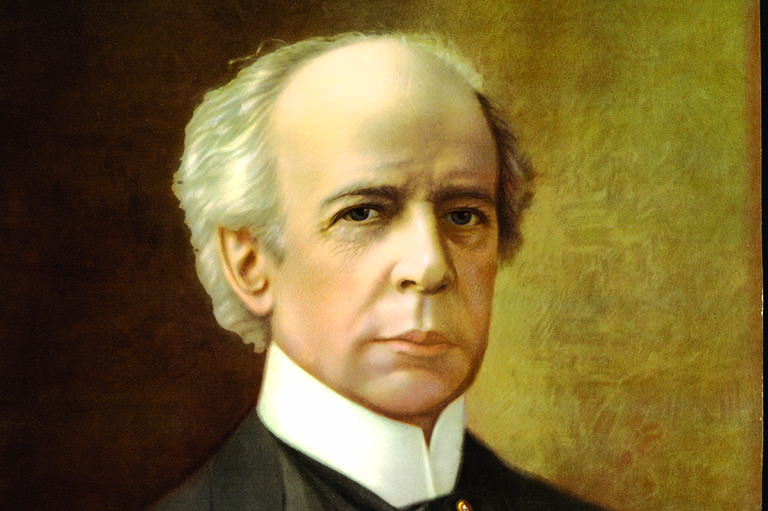

With an indication of further assistance from the Jewish Colonization Association, the BHI/HBS then began to explore the possibility of founding a new Jewish farm settlement in the West. In early 1892, there was a meeting with Prime Minister John Abbott in Ottawa followed by an exchange of letters to the government.

In a fourteen-point memorandum, W.H. Baker, clerk of the Baron de Hirsch Institute, asked for the conditions under which a Jewish settlement might be established in the West. The government’s position was clearly set out in a ten-page response from H.B. Small, secretary of the Department of Agriculture.

There was no objection to a new Jewish settlement, but a request for contiguous land for “a whole and undivided colony” was rejected as “undesirable in the interests of the settlers themselves.”

Nevertheless the Baron de Hirsch Institute, with financial support from the Jewish Colonization Association, did succeed in starting a new Jewish settlement not far from Oxbow, Saskatchewan.

It was called Hirsch after the great benefactor. The Jews were granted an area of land where they could file for alternate quarter sections under The Homestead Act among non-Jewish neighbours.

In 1900, the Jewish Colonization Association learned that “masses” of Jews in Romania were living in “the most frightful destitution ... due to the most refined persecution.”

Conditions for the Jews had become so intolerable that in the spring of that year more than 25,000 set out across Europe to Hamburg on foot. They became known as the foosegayer — literally “foot walkers,” and signalled the wholesale exodus of Jews to the United States; some also sought entry to Canada.

The JCA, however, was not a charitable institution in the ordinary sense. It could not disburse aid money freely — its mandate was to sponsor projects to help Jews become established in constructive pursuits. Thus it was that, as thousands of Romanian Jews were fleeing persecution in 1900, the JCA began its appeal to Ottawa, via London, for land to establish a new colony of Romanian Jews in the West.

In the spring of 1901, Laurier refused this request on the recommendation of his immigration minister, Sir Clifford Sifton. (Sifton had earlier told his immigration agent in Europe that he “objected to Romanian Jews as immigrants.”) By the time Laurier’s response reached London however, sixty-five Romanian emigrant families were on the high seas en route to Canada. They were not turned back, and eventually they started a new Jewish colony in Lipton, Saskatchewan. But Sifton’s report, in which he questioned the Jews’ suitability as farmers was influential, and did limit the size of the settlement.

This attitude was nothing new. When Canada opened its doors to immigrants in the late nineteenth century, the Jews were not included on the list of peoples invited to settle in this country. This was confirmed by W.D. Scott, a former immigration agent turned historian, when in 1913, he wrote on “Immigration by Races” in the Adam Shortt /Artthur Doughty series Canada and Its Provinces.

Scott candidly discussed all immigrant groups, categorizing them as either “desirable” or “undesirable.” Negroes, Chinese, Japanese, Galicians, Italians, and Jews were in the undesirable category. Of the Jews he said, “No effort has ever been made by the Government of Canada to induce Jewish immigrants to come to the Dominion and the influx [of Jews] has been entirely unsolicited.” Scott was undoubtedly writing from his experience, beginning in 1891, as an immigration agent.

In the late 1890s, the government was still following the policy, adopted soon after Confederation, to encourage only farmers and domestics as immigrants, to discourage and prevent the entry of indigents and undesirables, and to limit the settlement of immigrants in the cities. A negative attitude toward Jews arose from this policy, but there was no legal bar if they could pay the landing fees imposed by order-in-council.

But this attitude was again demonstrated in the summer of 1900, when about 2,000 Romanian refugees arrived in Canada, some of them having been turned away from U.S. ports.

In July, Jews aboard two ships in the Montreal harbour, the S.S. Montfort and S.S. Lake Champlain, were not permitted to disembark. On leaving Europe they had been told they needed $5 to $10 each to qualify for landing as nonpaupers.

While they were in transit, however, the Canadian government changed the landing money requirement to $25 per person. In addition the government suddenly announced a ban on sending any more people to the West.

The problem of the Romanian Jews was reported regularly in both the Jewish and mainstream press.

The issue came up in Parliament when a Toronto M.P., citing a report on poverty-stricken Jews coming to Canada, asked if Canadian agents in Europe were “catering for that class of people.” Sir Wilfrid Laurier responded that it was not the policy of the government “to bring out paupers,” but there was no restriction against “able-bodied men who were able and willing to work.”

On July 22, David Ansell, president of the BHI/HBS, advised the society’s board of a telegram from James Smart, deputy minister of the Interior, complaining about the arrival of “undesirable Romanian Jewish immigrants” andwarning that if Jewish immigration continued, the government would have to “take steps to prevent it.”

Some board members wanted to send a delegation to call on the minister, but Ansell offered instead to write to Prime Minister Laurier and “endeavour to see him,” to discuss the issue of the Romanian immigrants still detained on board the Lake Champlain.

When the prime minister had not replied to Ansell’s request for an appointment by early August, the BHI/HBS board held a special meeting August 5.

At this meeting it was unanimously resolved to advise the immigration department that the BHI/HBS was prepared “to take charge of the Romanian Jewish immigrant passengers on board the steamer Lake Champlain, so that they shall be no charge on the country.”

This resolution was sent to Clifford Sifton, minister of the Interior, and to John Hoolahan, the government’s local immigration agent.

On August 9, David Ansell again wrote to Laurier explaining that the organization’s purpose was to prepare for the acceptance in the country of 600 to 700 Jewish immigrants and you will have read from our papers of yesterday and today the dismal state they are placed in by our Government inducing them to emigrate and on landing ... being told that the laws of the land forbid that they should go inland without having $25.00 per capita. ... These unfortunates have been misled by the agents of the Government and I think in the cause of humanity that they should not be turned away from our shores.

Ansell appealed to Laurier’s “sense of fairness ... to devise some means of rectifying the unjust action of your Government.” He also wrote to the Jewish Colonization Association in Paris with a copy of his letter to the prime minister advising that the increased landing charge was “practically aimed at the Romanian Jews who were mostly in a destitute condition.”

On August 12, Ansell reported receiving a reply from Laurier, but its contents were not recorded. By September 18, the problem of the Romanian immigrants was resolved, but there is no word on how this came about. Between July 16 and late October, a total of 2,019 Romanian Jews arrived in Canada. Of these, 509 were sent to the U.S., 783 remained in Quebec (mostly in Montreal), and 139 went to Toronto. The remainder went to seventeen other centres in Canada, including Cape Breton (47), Winnipeg (79), Brandon (2), and Oxbow (10).

At the annual meeting of BHI/HBS on October 28, 1900, the board delivered a report which detailed the difficulties of the Romanian immigrants. It cited the order-in-council, passed in July of that year, “prohibiting the embarkation of undesirable immigrants,” and noted its subsequent reversal after the board provided certain guarantees.

It was also reported that the Government were reimbursed the sum paid for food to the first arrivals in Winnipeg before the prohibition was placed on that town by the Department of the Interior. Your Board at the same time reminded the Government that the Hebrew immigrants to Canada had never ... been an expense to the Government or a burden upon the country.

The funds for this extraordinary outlay by the BHI/HBS came from the JCA office in Paris.

On November 7, 1900, there was a general election marking the end of Laurier’s first term in office. In spite of the difficulties with the government over the Romanian immigrants, on November 2, The Jewish Times wholeheartedly commended Laurier and the Liberal party to its readers as worthy of reelection. A special election supplement in Yiddish was included with this edition, along with a photo portrait of Laurier “worthy of framing and preserving.”

The Jewish Times also disclosed in an editorial comment that there had been a meeting of Jewish electors, which should never have been held because it is unwise for Jews to segregate themselves in this manner ... (where) an attempt was made to bring discredit on the government for its action in relation to the Jewish immigrants from Romania. ... The speakers ... spoke as if hundreds of these people still languished on shipboard.

The Jewish Times called the critics’ comments “a brazen perversion. of truth” and a “gross calumny of the government, which proved its liberality and kindness to the Jewish refugees by permitting them all to land.”

The writer of the article further elaborated on this “liberality” by quoting the expressed views of Laurier in calling for “justice,liberty, and equality to every man, woman, and child,” and stating, “Canada has room for one great united people; it has no room for jealous divisions and racial hatreds.”

The article does not disclose who called the meeting, nor what transpired there. But it was obvious that the “uptown” Jewish leadership had its critics probably drawn from the “downtown” newcomers.

Clearly, some Jews were not prepared to overlook the way in which the government had treated the immigrants from Romania.

In 1900 Herman Landau was also trying to assist the exodus of Jews from Romania to Canada.

That summer the BHI/HBS board was advised of a cable received by the Elder Dempster Steamship Company “from a Mr. Landau in London, informing that 200 Romanian youths were coming over by S.S. Lake Ontario, and placing at the disposal of the company the sum of $1,000 to obtain them employment.”

The BHI/HBS was asked to cooperate in receiving this group. It was decided, however, that the Society “had as much as they could possibly do with the immigrants coming direct from the Jewish Colonization Association.”

Therefore they could not do anything for these 200 people. The board also said it “had no cognisance [sic] of Mr. Landau.”

If he had wanted their help, it said, he should have communicated directly with them. In practical terms this decision was a rejection of Mr. Landau, rather than of the immigrants on the S.S. Lake Ontario since there is at least one reference to people from that ship being assisted.

By 1905, it appears that Landau did become known to the leaders of the BHI/HBS.

The organization’s 42nd annual report refers to the “Jewish Sheltering Home,” established in London by “the eminent philanthropist, Herman Landau,” being taxed to its utmost capacity, due to a new, large influx of Russian immigrants, brought about primarily by the effect of the Russian-Japanese War.

Several hundred of the people in the Sheltering Home were sent to Canada at that time.

The 1905 report also stated that the BHI/HBS board “has communicated with the philanthropist, Mr. Landau, and assured him of its willingness to cooperate with him when necessary in his acts of benevolence.”

Having thus been recognized in the fall of 1905 for his philanthropy, it is not surprising that the news of his lecture in London a few months later caused a stir among Jews in Canada.

The Laurier “promise” was also seized upon because the debate on the Lord’s Day Act (which would ban work on Sunday) was then getting into high gear.

That act would compel observant Jews to limit their work week to five days, with Sunday a legislated holiday and Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, a religious one. (Its enactment eventually contributed to the weakening of Jewish Sabbath observance in Canada.)

The government had sponsored the bill, but Laurier himself showed support for a compromise approach that would take into account the views of seventh-day minorities.

Thus Landau’s disclosure of Laurier’s 1897 “offer” of a territory where Saturday might be observed in place of Sunday gave hope to those who sought a Lord’s Day Act exemption for observant Jews, as well as to those who fostered the idea of Jewish cultural autonomy.

Moreover in late 1905, Laurier had appeared at a Zionist rally in Ottawa called to protest the 1903 and 1905 pogroms in Kishinev (capital of Russian Moldavia).

“We cannot bring all the Jews of that country to Canada,” Laurier said, “but we can extend a hearty welcome to those who choose to come.”

Landau’s reported address, coming soon after Laurier’s remarks in Ottawa, revived hope for a new Jewish farm settlement in the West. In May 1907, the London Jewish Chronicle interviewed the prime minister in Ottawa on this question.

Laurier stated that the Canadian government had been approached with a plan to form a colony (probably by the Baron de Hirsch Institute), “but we refused to entertain it.”

And, he added, “We have granted privileges of this description before but they did not work satisfactorily and will consequently not be repeated in the future.”

Asked whether he might look more favourably on a series of small colonies rather than one large one, he responded: “No, we (are) not prepared to sanction such colonies. To allow Jews to form ... a separate organization is impossible. We would not allow that to Jews or to any other body.”

Despite this reply, Laurier was asked specifically about his objections to “local autonomy” for a Jewish settlement, as proposed by the Jewish Territorial Organization (The JTO, at that time, dissenting from the World Zionist Congress decision to seek Jewish colonization only in Palestine, sought a territory for autonomous Jewish settlement wherever it might be practicable).

The P.M. responded: “I suppose there would be Gentiles as well as Jews in such a colony .... and all would take the usual chances of election.” Laurier said that Jews were welcome as individuals, “but I must tel1 you,” he added, “that we encourage no immigrants except ... agriculturists, farm laborners and domestic servants.”

There could hardly have been a clearer disavowal of the possibility of Jewish cultural autonomy than that given in this interview. Nevertheless, a number of Jewish leaders held on to the notion that such a vision could be realized in Canada.

Later that summer, Israel Zangwill, the Anglo-Jewish author who was president of the Jewish Territorial Organization, sent a special emissary to Ottawa to attempt to negotiate an autonomous Jewish district. His effort ended in failure, of course.

Despite evidence to the contrary, B.G. Sack, the best-known Canadian Jewish historian in the first half of the twentieth century, in 1941 published his essay, “A Historical Opportunity Forfeited,” based on the press report of Landau’s 1906 lecture. And most writers of Canadian Jewish history, until recently upheld Sack’s version.

Two exceptions were Abraham Rhinwine and Simon Belkin. In 1916 Rhinewine, a supporter of the Jewish territorialist movement, wrote to Sir Wilfrid Laurier, then leader of the Opposition, and to Sir Robert Borden, who had become prime minister in 1911, asking them about the possibility of obtaining a district for Jewish settlement after the war, noting the earlier rejection a decade earlier.

In his book Der Yid in Kanada (1926, Yiddish untranslated), Rhinewine recounts that Laurier replied: It was not the policy of the Canadian Government, when I was in office, to grant any blocks of land to establish colonies of the same religious faith or of the same race; but we would welcome Jewish immigrants and give them homesteads on the prairies ... as they were available.

Prime Minister Borden referred the question to the minister of the Interior from whom there is no indication of a reply. Simon Belkin, in Through Narrow Gates (1966), repeats all the claims made by Landau in his 1906 lecture but points out certain discrepancies.

It was Belkin who disclosed that when Baron de Hirsch’s representative inquired about the possibility of a new settlement in Canada in 1889, be wrote to F.C. Mocatta, a vice-president of the Anglo-Jewish Association — not to Landau. Belkin also presents Rhinewine’s account of his 1916 exchange with Laurier.

The press report of Landau’s lecture, still the only source for his claims about Laurier and de Hirsch, states that Landau “discussed” with Laurier “the question of Jewish colonization.”

How and where the discussion took place is not disclosed. Perhaps it was no more than a casual encounter and the exchange of a few words that Landau embellished in his lecture almost a decade later.

As to Landau’s motives: he was genuinely dedicated to the cause of aiding persecuted Russian Jews. He knew about de Hirsch and the Jewish Colonization Association, even if he didn’t make it into the leadership of that organization.

He was also probably aware of strains that had developed in the political Zionist movement after the 1904 death of its founder, Theodor Herzl, and the subsequent founding of the Jewish Territorial Organization in 1905.

Surely it was no more than over zealousness that caused him to embellish his talk. Hopefully Laurier’s alleged promise to Herman Landau to grant the Jews an autonomous territory in Manitoba will now be seen as one promise this revered Canadian political leader never made.

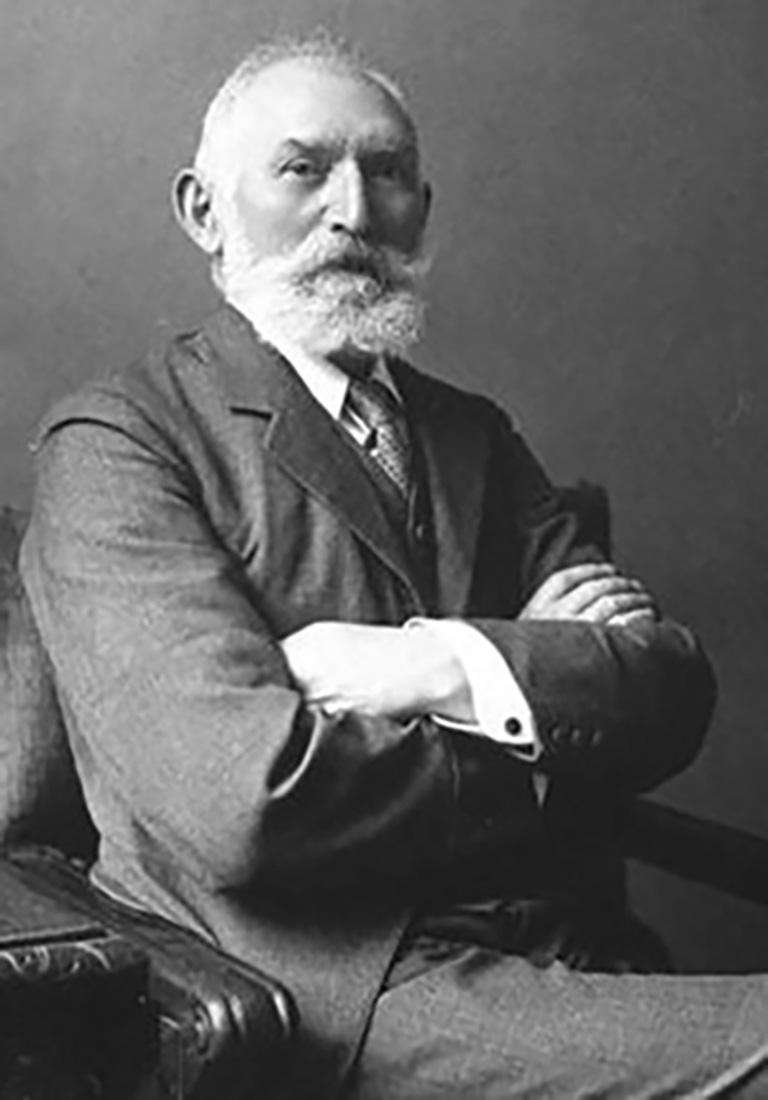

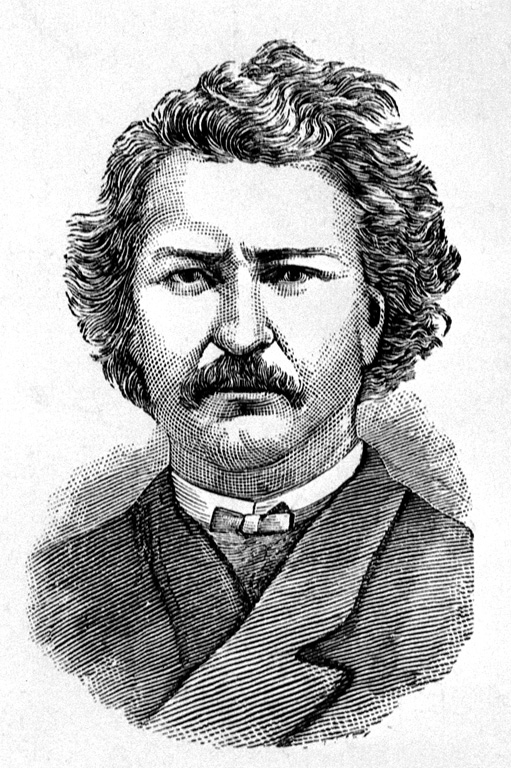

Louis Riel and the Jews

The first and only Canadian politician ever to include the Jews on a list of prospective immigrants was Louis Riel but this only came to public light long after Riel was executed.

In the diary that he kept during 1884–85, Riel expressed his views on race relations and on immigration. Proposing to invite people from nine European groups, including the Jews, to settle in Canada, Riel said, “I put aside opinions and disputes about the personal worth of the different races of men.” He called on the Jews to establish a “New Judea on the shores of the Pacific.” Riel wanted Manitoba reserved for “pure French-Canadian Métis”; he offered the ” Irish, Italians, Bavarians, and Poles [land] ... east of the Rocky Mountains” and the “Swedes, Norwegians, Danes, Belgians,and Hebrews [land] ... west of the Rocky Mountains.”

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!