Tolerance or Tyranny?

It was the fall of 1774. Somewhere in Mohawk territory, along the well-travelled corridor that ran from Canada, along Lake Champlain, down the Hudson River to New York, Mohawk leader Thayendanegea — also known as Joseph Brant — could see the birch, oak, and maple trees turning bright shades of red and gold. The beauty and tranquility of the season, however, belied the growing political turbulence roiling Anglo-American settlers in Massachusetts, directly to the east. Thayendanegea and other First Nations leaders were hearing disquieting rumours about a possible confrontation between New Englanders and the British Crown.

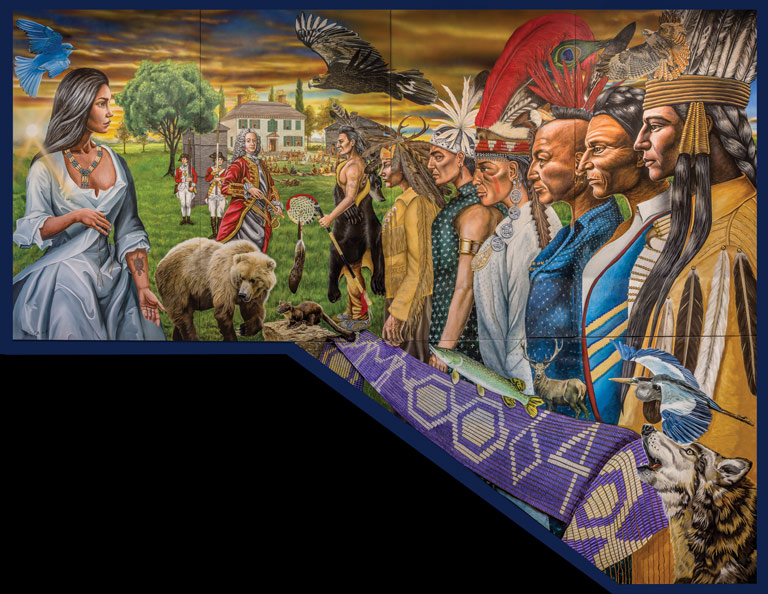

Within the Haudenosaunee Confederacy — an Indigenous alliance whose territory spanned an expanse of land to the south and east of Lake Ontario — the Mohawk, or Kanien’keha:ka, lived on the easternmost lands and were known as the Keepers of the Eastern Door. They had long found themselves at the centre of the region’s geopolitics, occupying an ancient trade route that divided the French settlers and their allied Indigenous villages along the St. Lawrence River valley from the Dutch, English, and Haudenosaunee people to the south. For generations, Haudenosaunee leaders like Thayendanegea had fought to maintain their autonomy amidst the recurring conflicts that had left so many scars on the land and its people.

With the fall of New France in 1760 and the end of the Seven Years War in 1763, the British had asserted their sovereignty over the territory previously claimed by the king of France. The end of the war between the two European powers had driven hopes among many in the region for a new era of peace and prosperity.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

A mere decade later, however, such hopes had been upended. Now, disputes between British-American settlers and British Crown officials were turning into a crisis. The events would pull the Haudenosaunee Confederacy apart — extinguishing the Council Fire that had long symbolized unity among the six confederated nations. And they would break up Britain’s North American empire, unleashing a chain of consequences that would lead to the creation of the United States of America and, later, to Canada. Those momentous events were fuelled, in part, by an act of British Parliament that aimed to appease Canada’s French Catholic settlers and to formally recognize Indigenous lands. It was called An Act for making more effectual provision for the Government of the Province of Quebec in North America and known more concisely as the Quebec Act.

This year marks the 250th anniversary of the Quebec Act of 1774. Unlike the Battle of the Plains of Abraham or the War of 1812, the Quebec Act has not found a place in the Canadian popular imagination. And yet its role in North American history was more significant than most people, including most historians, realize. The story of the Quebec Act focuses not just on French-speaking settlers in the St. Lawrence River valley and their English colonial governors; it also incorporates imperial officials in London, First Nations across the Great Lakes watershed and the Ohio Valley, rebellious colonists, ambitious land speculators in Virginia, Scotland, and England, and many others. In its broadest frame, the act was more than a North American event: It was a turning point in the history of a globalizing British Empire — the result of an overextended empire facing demographic, legal, religious, and cultural diversity unprecedented in its history.

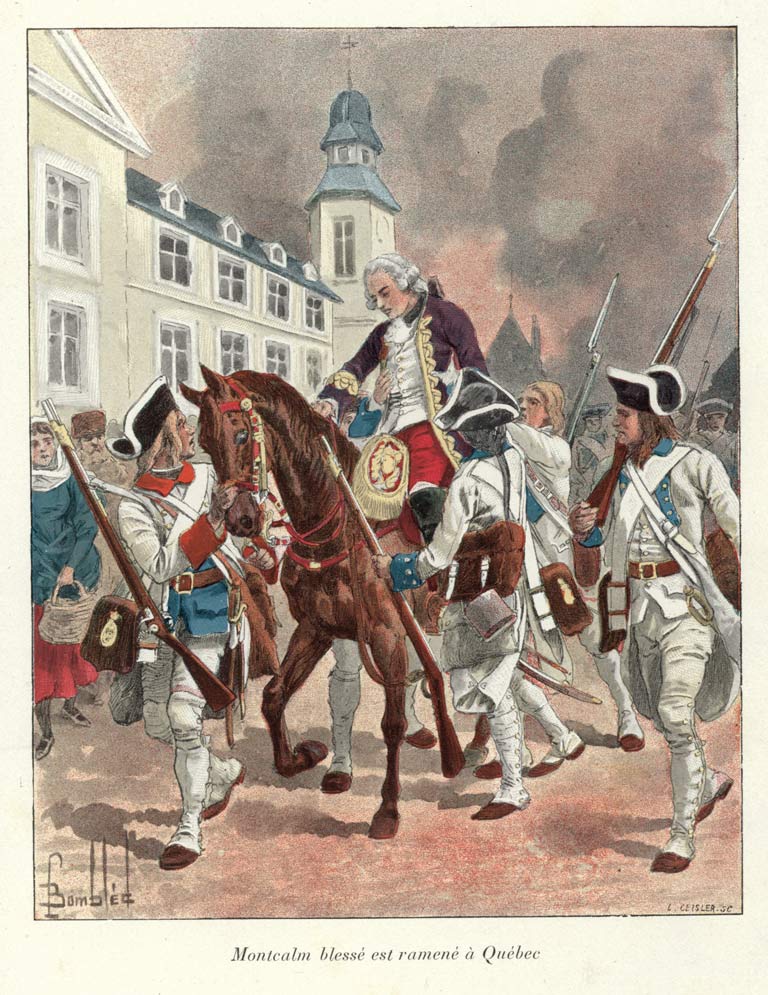

Our story begins in 1759, when French General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm’s army fell to British forces in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, presaging the end of French power in North America. By the time France ceded its claims on Canada to the British Empire in the Treaty of Paris in 1763, French-speaking people had lived along the St. Lawrence River for more than 150 years.

Through that long stretch of time, the French had pushed up the St. Lawrence River deep into Indigenous territory — across the Great Lakes watershed, into Anishinaabeg territory to the north and west where, to use the Ojibwe historian Michael Witgen’s term, an “infinity” of kinship-based Indigenous worlds had proliferated for centuries. French trade networks extended far north into Cree territory and south through the Illinois and Ohio river valleys, where merchants and voyageurs encountered, traded with, and married into Illinois and Miami societies. The networks continued up the Missouri River, deep into the lands of Siouan-speaking peoples, and down the Mississippi River, through Osage and Quapaw territory to the French beachhead of New Orleans. Across these vast distances, intrepid missionaries and fur traders integrated themselves into Indigenous kinship networks that stretched across the extensive river systems, creating an Indigenous-Metis-French world whose reach extended via the French Empire into the Caribbean and across the Atlantic Ocean to Europe and Africa.

That complicated world beat to rhythms of its own drums. Maps printed in London and Paris made it appear as though vast swaths of the continent could be transferred among French, British, and Spanish hands. But those maps reflected a fantasy of colonial possession more than any reality on the ground. In North America, areas of European military and demographic dominance extended only from the Atlantic coast to the Appalachian Mountains, in addition to a stretch along the St. Lawrence River and a few scattered settlements elsewhere.

Nonetheless, the collapse of France’s North American empire changed the continent’s geopolitics. France had long provided weapons and support to its Indigenous allies, creating a powerful counterweight against the pressures of creeping British settlement. With the French defeat, Indigenous nations in the interior were thrust into a more precarious position. British authorities assumed that they could impose their laws on the territories ceded by France. But Indigenous people had not capitulated in Montreal or in Quebec, nor had they signed any treaties in Paris. “Although you have conquered the French, you have not yet conquered us!” the Ojibwe Chief Minavavana warned a British trader. “These lakes, these woods and mountains, were left to us by our ancestors. They are our inheritance; and we will part with them to none.”

British officials proved deaf to such sentiments, however. And so, in 1763, Indigenous people took matters into their own hands. Led by the Odawa war chief Pontiac, or Obwandiyag, allied nations including the Ojibwe, Potawatomi, Illinois, Miami, Shawnee, Delaware, and others launched a series of devastating assaults on forts and settlements across the Ohio Valley, extending deep into Pennsylvania and Virginia. The vast uprising across the trans-Appalachian West panicked British imperial officials with the prospect of a costly new war, coming hard on the heels of their recent victory. The last thing they wanted was to send another army to North America — not at a time when they were desperately hoping to reduce expenses, pay off the massive debt accumulated in the Seven Years War, and figure out how to assert control over the gigantic swaths of territory they’d won in North America, the Caribbean, and India.

Great Britain responded with a set of momentous concessions, enshrined in the Royal Proclamation of 1763. The proclamation created three new provinces in North America — including Quebec — and one in the Caribbean. It also laid down principles intended to protect Indigenous land rights. It “reserved” the territory west of the Appalachian Mountains for First Nations people “with whom we are connected, and who live under our Protection,” forbidding the grant of property titles in the area and outlawing real estate transactions between Indigenous people and British settlers, land companies, or provincial assemblies. From 1763 on, only Crown authorities would have the legal authority to purchase Indigenous lands.

Advertisement

While the Royal Proclamation established a temporary peace in the west — and a very long-term precedent that Indigenous land cessions had to be mediated by the Crown — it angered British-American settlers along the coast. For decades, officials and residents from New England to Virginia had hoped to push west into the Ohio Valley. Having defeated the French in the hope of opening those lands to speculators and settlers, they suddenly found their ambitions thwarted by imperial officials in London. From their perspective, that land was the reward for the enormous sacrifices they had undertaken during the Seven Years War.

By replacing the French in the Ohio Valley, the British were pulled into a world they hardly knew: a fluid, highly mobile, and decentralized Indigenous world, where European claims of sovereignty remained exceedingly tenuous. Only by strengthening their own networks of Indigenous alliances could British officials hope to assert their influence. The oldest and most important of British allies were the Haudenosaunee, centred along the Mohawk Valley, and the Cherokee, positioned along the Tennessee River. Controlling two major waterways into the Ohio Valley, these two groups of Iroquoian-speaking people in the north and south became the key to British control of the region.

In the face of relentless pressures from land-hungry settlers pushing across the Appalachians — and in recognition of already-existing settlements in regions that now encompass Kentucky and Tennessee — Haudenosaunee and British diplomats renegotiated the boundaries of Indigenous territory in 1768. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix opened a vast section between the Appalachian Mountains and the Ohio River to white settlement and speculation while closing off Haudenausonee territory along the upper Susquehanna River. Leaders like Thayendanegea hoped the line drawn at Fort Stanwix would serve as a permanent frontier, keeping English settlement from crossing the Ohio River.

In the years that followed the Fort Stanwix Treaty, British authorities continually insisted that they would keep white settlement out of Haudenosaunee territory. But those promises were too often broken. “We are sorry to observe to you that your People are as ungovernable or rather more so than ours,” Seneca Chief Serihowane chastised the British superintendent for Indian affairs in the northern colonies, William Johnson, in 1774. “It seems, Brother, that your People entirely disregard and despise the settlement agreed upon by their Superiors and us.”

Why were British officials so eager to keep their settlers out of the continental interior? One major reason was the strength of Indigenous power and the desire of First Nations to hold on to their lands. But there was another important reason as well. British officials hoped to channel settlement in other directions: to the colonies of East Florida and West Florida, newly wrested from the Spanish; to Nova Scotia, whose French Acadian population they had deported just a decade earlier; and, of course, to the St. Lawrence River valley, the heartland of now-defunct New France, where they hoped that a giant wave of Protestant Britons would outnumber, dominate, and eventually assimilate the French Catholic inhabitants.

Although the 1763 Treaty of Paris ending the Seven Years War gave residents of the former New France the option of leaving for France, few accepted. Members of the military nobility faced doubtful prospects in Europe; in Canada, by contrast, they were firmly rooted by trade networks and by the socio-economic power they wielded as landowners. Unsurprisingly, most chose to stay. The prosperous communities of Canadian merchants in Quebec City and Montreal made the same calculation and arrived at the same decision. Among the elite, only the members of the civil administration left in significant numbers. As for the artisans and peasants, they remained attached to the society into which they had been born. The settlers of French ancestry in the St. Lawrence River valley, with their growing sense of collective identity, posed an obvious threat to British sovereignty. Perhaps, officials in London hoped, the large-scale immigration of Anglo-Protestant settlers could neutralize the Canadian influence.

In pursuit of this goal, the British Board of Trade, led by the Anglo-Irish proprietor Wills Hill, 1st Earl of Hillsborough, implemented policies to attract Protestant migrants to the new territories and keep them out of the trans-Appalachian west. A 1763 Board of Trade memorandum outlined the steps needed to implement the policy in Quebec: It proposed establishing a capital named British Town to be settled by new migrants who would bring with them “the English language, the English manners, & a Spirit of Industry, among the French Canadians.”

It was not long, however, before British imperial control ran up against realities on the ground. Within several years, the demographic and political situation in the St. Lawrence River valley (and elsewhere in the empire) had made itself manifest. Aside from a small but notable cohort of Scottish merchants, no waves of Anglo-Protestant migration were flooding into Quebec. Meanwhile, the French-speaking Canadian settlers retained a firm hold on the lands bordering the St. Lawrence River. Unless British officials were willing to embark on a gigantic population removal far more challenging than the Acadian expulsion of 1755 — and they were not — they had no choice but to find an accommodation. They would need to develop forms of imperial governance that were more open to cultural and religious diversity, and firmer in curbing colonial autonomy, than anything that had been tried before.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

In furtherance of this vision, British officials began to develop strategic alliances with prosperous families of merchants and artisans who formed an educated petite bourgeoisie in Quebec and Montreal — a group willing to offer its services to the new imperial state. These literate Canadians had largely ensured the operation of the colonial administration after the departure of the French civil administrators. They also embodied a vibrant French-speaking public opinion.

Ensuring the participation of Canadians in the political and administrative structures of the colony required more than mere accommodation to the principles of cultural and religious toleration, however. It required an institutional recognition of the Catholic Church itself — which not only served religious functions but also ran institutions like schools and hospitals. That was a pretty tall order, given that — ever since King Henry VIII had broken with Rome in 1534, declared himself Supreme Head of the Church of England, and launched that country’s Protestant Reformation — England had been waging what many of its fiercely religious subjects understood as an apocalyptic struggle between Protestant freedom and Catholic slavery to a Roman Pope. Local authorities would have to proceed cautiously.

In June 1765, the Board of Trade in London received a report urging that Canadians “not [be] subject to the incapacities, disabilities, and penalties to which Roman Catholics in this kingdom are subject by the Laws thereof.” According to historian Philip Lawson, this was the moment when officials in London definitively abandoned the vision of a Protestant Quebec. It represented a turning point in the history of British imperial governance and of the principle of religious tolerance. (It would take more than half a century before Catholics in Britain would be granted such rights with the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829.)

On June 29, 1766, Monseigneur Jean-Olivier Briand — a high-ranking Quebec clergyman who had adopted a conciliatory attitude toward the British conquerors — returned from a trip to England and France, where he had been consecrated, and triumphantly disembarked at Quebec as the colony’s new Catholic bishop. The Catholic Church had become the authorities’ preferred representative of the Canadian people. And, thanks to a particularly efficient system of cultural and moral regulation, the clergy had become the main guarantor of Canadians’ loyalty to their new masters.

When Guy Carleton replaced James Murray as governor of Quebec in 1766, adherents to ideologies of Anglo-Protestant supremacy hoped for a return to policies of forced assimilation. Those hopes were soon dashed, however: The new governor continued his predecessor’s policies, ignoring the demands of British merchants and forming even closer ties to the traditional Franco-Catholic elites.

Between 1766 and 1774, Carleton and a group of experts in colonial affairs developed and drafted what would become the Quebec Act. In its drafting, the Earl of Shelburne, the Crown official in charge of American affairs, placed particular emphasis on Great Britain’s responsibility to recognize certain rights of the peoples it conquered. Although an assimilationist vision prevailed in the early stages of drafting the Quebec Act — with authorities assuming that French law would eventually give way to British law — this vision disappeared from later drafts, as demographic realities became clear to policy-makers in London.

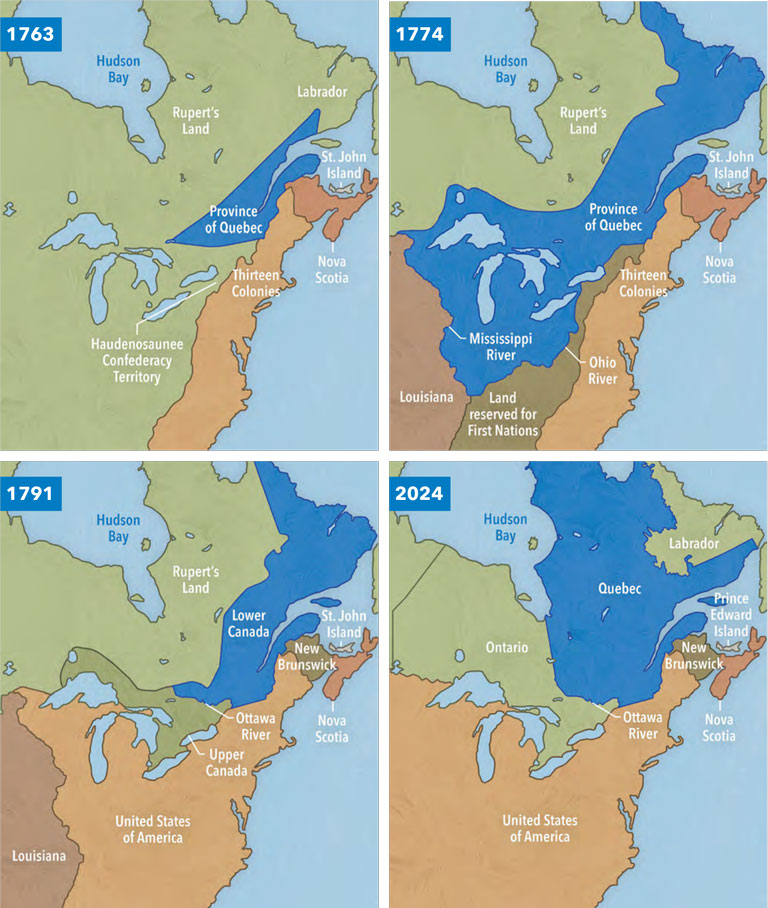

The final bill, presented by Carleton to the British Parliament in May and June of 1774, perpetuated the social, legal, economic, administrative, cultural, and territorial frameworks that Canada had inherited from the French regime and applied them to a British colony named “Quebec” that stretched from the shores of the Labrador Sea to the St. Lawrence River, west to the Great Lakes and the Mississippi and Ohio river valleys, deep into North America’s continental interior.

By extending Quebec’s borders down the Ohio River, the Quebec Act reinforced the boundary between Indigenous and settler territory negotiated at Fort Stanwix in 1768. It built on long-standing Indigenous and French travel routes connecting the Ohio and the St. Lawrence river valleys, and it reoriented trade and governance in the region away from the American seaboard colonies. It signalled that British authorities would privilege their alliance with Indigenous power in the region — Haudenosaunee power, especially — over the interests of the rebellious, land-hungry settlers. As one British official wrote from London, the act had “the avowed purpose of excluding all further settlement” in the Ohio Valley. As another British official put it, the expanded province of Quebec would serve as “an eternal barrier ... [a] Chinese wall.”

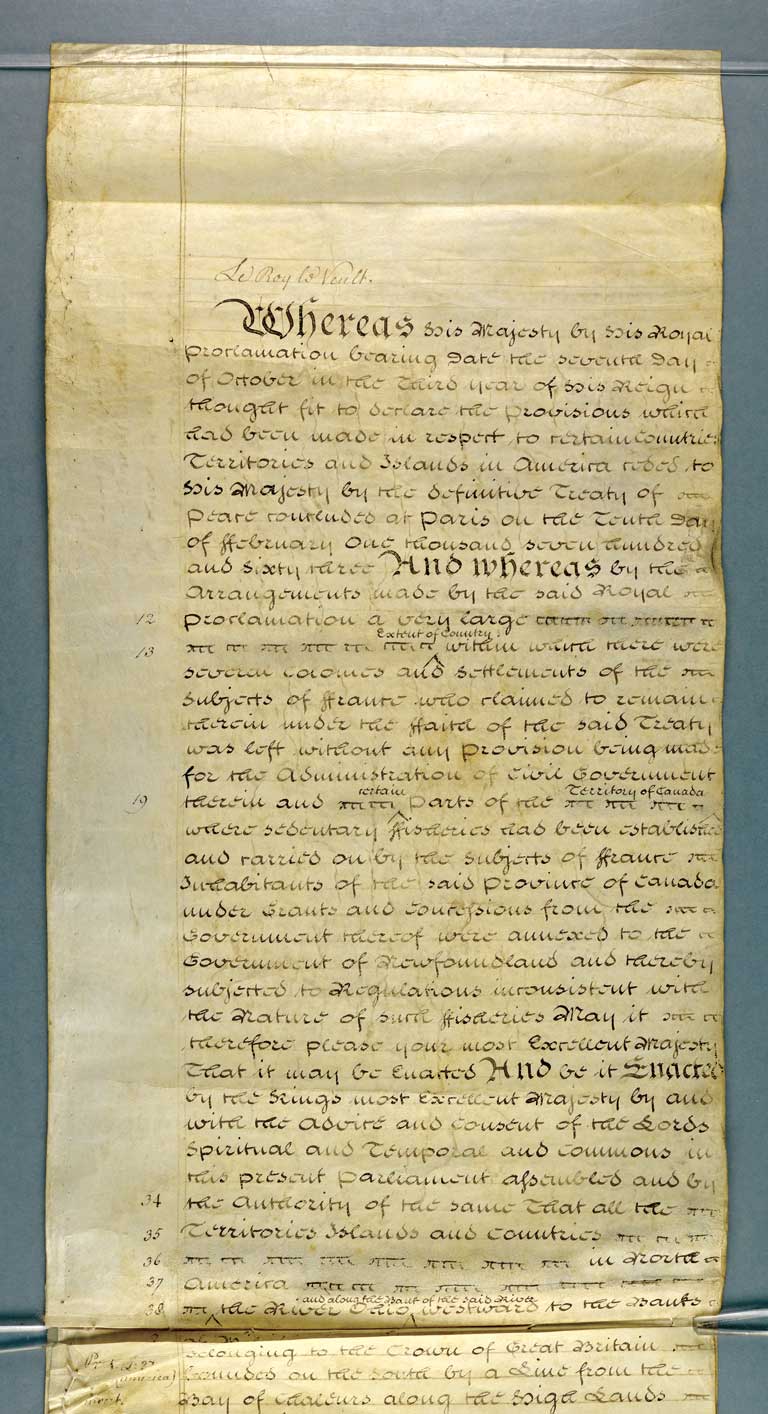

An Act for making more effectual provision for the Government of the Province of Quebec in North America was approved by a large majority in the British House of Commons on June 18, 1774, and received royal assent four days later. Coming into force on May 1, 1775, the Quebec Act represented what historian Hannah Muller called “a new vision of governance.” It marked the moment, as she put it, “when a truly imperial subjecthood was imagined and realized — a subjecthood that could accommodate the many people and the many laws of the British Empire.”

From this perspective, it is surely one of the great historical ironies that this new vision — this expanding understanding of an empire that could accommodate a variety of religions and ethnicities — also marked the greatest crisis thus far in the British Empire’s history. When news of the Quebec Act reached Britain’s Thirteen Colonies on America’s Atlantic seaboard — already in the midst of angry rebellions against taxation — it created a veritable explosion. “The King has signed the Quebec Act,” wrote Ezra Stiles, future president of Yale University, “extending the province to the Ohio & Mississippi and comprehending nearly two thirds of the territory of English America, and establishing a Romish Church & IDOLATRY over all that space.” How, Stiles wondered, could British officials “expressly establish Popery over three quarters of their Empire”?

For Protestant Americans throughout the seaboard colonies, the Quebec Act was an appalling example of British tyranny. Passed amidst other responses to the colonial rebellion — acts that closed the port of Boston to maritime traffic, abolished an elected body in Massachusetts, and centralized power in the hands of the Crown governor — the Quebec Act looked to many colonists like a repudiation of traditional English liberties.

Here was the British government extending religious rights to Catholic subjects in Canada and protecting land rights of Indigenous people in the Ohio Valley, even as it cracked down on the political rights of Protestants in New England. Scarcely a decade had passed since Anglo-American colonists had fought and died to defeat the French and First Nations alliance that had so long stood on their western fringes (more than one-third of New England men had served in the armed forces during the Seven Years War). And yet, upon their greatest triumph and the upsurge of patriotism that swept across the Thirteen Colonies, here was the British government returning a vast part of that western land to officials in Quebec.

Those colonists quickly added the Quebec Act to their tally of “Intolerable Acts” — a set of draconian laws passed in the British Parliament to crack down on Massachusetts in the wake of the Boston Tea Party. The act helped to push those colonists to armed rebellion, and eventually to revolution and the breakup of the British Empire. After the American Revolution, when the newly recognized United States of America negotiated its treaty of independence in 1783, its diplomats were able to secure the rest of the Ohio Valley all the way to the Mississippi River as part of their new nation. Haudenosaunee leaders were appalled. “They were the faithful allies of the King of England,” insisted Thayendanegea’s nephew Kenwendeshon (Aaron Hill). “He had no right Whatever to grant away to the States of America, their Rights or properties.” But the devastation wrought by American forces on Haudenosaunee territory left them little ability to resist.

Although jockeying between the United States and Britain for the Great Lakes region would continue for several decades — and the War of 1812 would briefly reopen the possibility of an internationally recognized Indigenous territory north of the Ohio River — the intervening years gave the United States precious time to consolidate national power at the expense of Indigenous land rights.

Although the borders established by the Quebec Act did not hold, its legacy lived on. The act marked the first time the British Empire officially recognized the rights of Catholics on a large scale. (It had previously done so in two much smaller places: the Mediterranean island of Minorca and the Caribbean island of Grenada.) The Quebec Act previewed the future recognition of minority religious rights elsewhere in the Empire — and, eventually, in Britain itself. In this regard, it anticipated the form the British Empire would take in the nineteenth century, as it expanded beyond settler colonialism toward other forms of colonialism using legal pluralism as a strategy of governance.

In North America, the Quebec Act helped to keep Canada in the British Empire. Rebellious American colonists believed that French Canadians, forcefully incorporated into the British Empire just a decade earlier, would inevitably ally with the movement for U.S. independence. The Articles of Confederation that governed the new United States made the admission of Canada — but no other colony — automatic. But the French settlers never rose up as the Americans expected. They saw no reason to ally with the traditionally anti-Catholic colonists over an increasingly tolerant British Crown.

As for the colonial elites, with their religious and seigneurial land rights guaranteed by the Quebec Act, their interests had been successfully fused to those of Britain. Shortly after the American Revolution, Crown authorities began a policy of attracting settlers north of the Great Lakes with generous grants of land and promises of low taxation. By 1791, a new Constitutional Act replaced the Quebec Act and created the provinces of Upper and Lower Canada. Quebec was firmly, if ambivalently, ensconced in the British Empire.

Advertisement

The Quebec Act also laid the groundwork for Quebec’s complex place within Canada. By guaranteeing Catholics the free exercise of religion, the act maintained the power of the Church, making it a central pillar of Quebec identity for two more centuries. Not until the Quiet Revolution of the 1970s was the Church’s grip on the province’s educational institutions and many of its social services finally challenged. By recognizing French civil law, the Quebec Act also established the dual legal regimes that continue today. French law still governs Quebec jurisprudence in many matters, and three seats of the Supreme Court of Canada are reserved for Quebec.

The legacy of the Quebec Act for Indigenous people was more ambivalent. For First Nations leaders like Thayendanegea, the act had initially offered a hope of reserving the lands west of the Ohio River as permanent Indigenous territory. When British diplomats ceded the vast area between the Ohio and Mississippi rivers south of the Great Lakes to the United States — renouncing the territorial claims the Crown had made in the Quebec Act — it was another great betrayal of Indigenous land claims by European powers. In certain ways, it was the most inexplicable one, since American arms had never conquered that territory during the war. Thayendanegea and his people moved across the border into the area that would soon be known as Upper Canada. There, as in the United States, the Haudenosaunee and many other First Nations continued — and continue — their valiant struggle to maintain their land rights and cultural traditions against the relentless onslaught of settlement and dispossession.

Quebec’s Changing Borders

Major Provisions of the Quebec Act

In addition to territorial expansion, the Quebec Act contained several important provisions that shaped the province for centuries:

- Article V declared “that his Majesty’s Subjects [in Quebec] ... may have, hold, and enjoy, the free Exercise of the Religion of the Church of Rome ... and that the Clergy of the said Church may hold, receive, and enjoy, their accustomed Dues and Rights.”

- Article VIII guaranteed that citizens of Quebec “may also hold and enjoy their Property and Possessions, together with all Customs and Usages relative thereto, and all their other Civil Rights ... and that in all Matters of Controversy, relative to Property and Civil Rights, Resort shall be had to the Laws of Canada.”

- Article XI stated that “the Criminal Law of England ... shall be observed as Law in the Province of Quebec.”

- Article XII eschewed an elected assembly and created “a Council for the Affairs of the Province of Quebec” with seventeen to twenty-three members whom “his Majesty ... shall be pleased to appoint.”

In today’s environment of misinformation and disinformation, it can be hard to know who to believe. At Canada’s History, we tell the true stories of Canada’s diverse past, sharing voices that may have been excluded previously. We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past, highlighting our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages – award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts. Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement