The Great Flag Debate

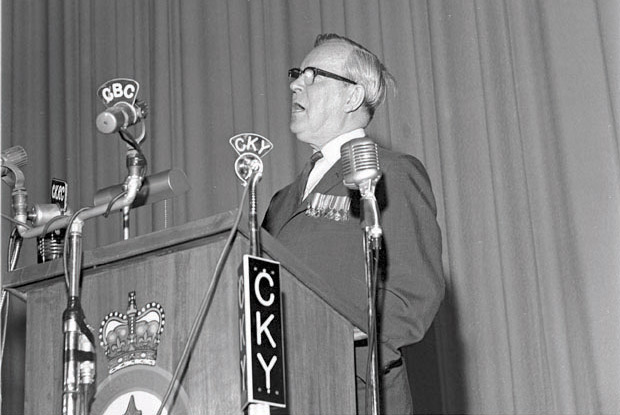

For Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson, travelling to Winnipeg on May 16, 1964, was a bit like the biblical Daniel walking into the lion’s den. The lions he was about to face were veteran members of the Royal Canadian Legion gathered at their national convention.

They knew he was coming to sell them on his proposal for a new flag with a maple leaf design and to retire the Canadian Red Ensign under which Canadian soldiers had fought and served. And some of them were prepared to roar with disapproval.

During the flight to Winnipeg aboard the government Jetstar, Pearson thumbed through marked issues of the Legion’s magazine — the Legionary — and calmly read every adverse article that had been written about his flag proposal. The cover of the magazine — which bore a Canadian Red Ensign with the caption “This Is Canada’s Flag: Keep It Flying” — said it all. But if Pearson, who headed a minority Liberal government, was nervous, he didn’t show it.

“Nothing appeared to bother him,” recalled John Matheson, the Ontario Liberal MP who accompanied Pearson on the trip and played a key role in the flag drama. “When he stepped off the plane in Winnipeg and mingled with the legionnaires, it was obvious that he felt at home and relaxed.”

The next day, Pearson entered the jam-packed Capitol Theatre in the city’s downtown and faced about two thousand delegates, many of them wearing Red Ensign pins in silent protest. As he stepped to the podium, the audience could see that the prime minister was wearing his set of medals from the First World War, a reminder that he was one of them.

He then launched into a passionate speech about patriotism, service to the country, and the importance of “pride in our nation and its citizenship.” The key point of his remarks was that Canada needed a flag that would be relevant to all Canadians, not just those of British descent.

“I believe that today a flag designed around the maple leaf will symbolize ... will be a true reflection of — the new Canada.” His remarks received polite applause in addition to loud boos and hisses from a minority in the audience. Legion president Judge Clare C. Sparling twice jumped to the podium to call the members to order. Pearson laughed, shrugging off the interruptions and continuing with his speech. The great Canadian flag debate had now officially begun.

The debate would rage for more than six months, cause acrimony in the House of Commons, unleash an emotional debate among Canadians everywhere, and, in the end, do little to unite the country.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Until the adoption of the Maple Leaf, Canada did not really have a flag of its own. After Confederation in 1867, Canada used the Union Jack and then the Red Ensign as it flags. Both were symbols of the country’s historic connection to Britain.

During the 1920s and 1940s, Liberal Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King considered the adoption of a new flag, but there was little support for it. Instead, by an order-in-council passed on September 5, 1945, the Canadian Red Ensign — which as of 1921 featured the Union Jack and the shield of the coat of arms of Canada with three maple leaves at the bottom — was designated as the flag that was to be flown on all federal buildings “until such time as action is taken by Parliament for the adoption of a national flag.”

In Pearson’s opinion, the time for such action had arrived in early 1964. Canada, he believed, was on the brink of a major crisis. The rising tide of Quebec nationalism threatened the survival of Confederation. As Pearson recalled in his memoirs, “the flag was part of a deliberate design to strengthen national unity, to improve federal-provincial relations, to devise a more appropriate constitution, and to guard against the wrong kind of American penetration.”

Pearson had first concluded that Canada needed its own official flag when he was secretary of state for external affairs in the 1950s. Once he became Liberal Party leader in 1958, he supported the inclusion of a new flag in the party’s platform. At a rally in 1961, he promised that “a Liberal government will establish a distinctive Canadian flag within two years of taking office,” a commitment that was reiterated during the 1962 and 1963 federal election campaigns.

Once in power, Pearson was true to his word. He assigned the task of conducting the initial research on a new flag to Matheson, the MP for Leeds in eastern Ontario. Matheson was of Loyalist heritage, a wounded veteran of the Second World War, a distinguished lawyer, and a member of the Heraldry Society of England. He was also later involved in the creation of the Order of Canada.

“Everybody seemed to assume that [producing a suitable flag] would be a straightforward, simple matter,” Matheson later wrote. Matheson, Pearson, and every other Liberal soon discovered how wrong that assessment was.

As Pearson’s biographer John English pointed out, “1964 was one of the worst political years in Canadian history.” As the head of a tottering minority government besieged by scandals, Pearson hoped a new flag would serve as “an elixir that might transform followers, wearied of the parliamentary battles and sad at heart as their heroes fell. Moreover, in the races against national division, a new flag might be a rallying symbol,” said English.

By the spring, following discussions with Matheson and others, Pearson had a fairly good idea of what a new Canadian flag would look like: two blue bars, top and bottom, with three maple leaves on a white background.

Later this design was modified by war veteran Alan Beddoe, an artist, who placed the blue bars vertically to symbolize Canada’s motto of a dominion “from sea to sea.” Much to Pearson’s annoyance, this design was soon derided by the Conservatives and their allies in the press as the “Pearson pennant.”

A group in support of keeping the Red Ensign as Canada’s flag demonstrates on Parliament Hill on June 1, 1964. RCMP were out in full force to ensure there were no clashes between these protesters and an opposing group supporting a new flag.

Yet Pearson pressed on. Demonstrating the “courage of a Roman gladiator,” as an editorial in the Hamilton Spectator described it, Pearson broached the subject of the flag at the Royal Canadian Legion branch in Espanola, Ontario, in his home riding of Algoma East in early May.

In his speech, he made the case for the uniqueness of the maple leaf as a Canadian symbol and expressed to his skeptical audience “the pride he felt at wearing the maple leaf badge” as a Canadian soldier during the First World War.

He next met privately with eight Ottawa journalists to survey their opinions of the three-maple-leaf flag design that he was about to publicly unveil.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The intimate gathering was supposed to be off-the-record — at least according to Richard O’Hagan, Pearson’s press secretary — but Walter Stewart of the Toronto Star, one of the reporters O’Hagan had invited, broke the unwritten protocol (he later denied he had done anything wrong) and wrote an article about the new flag. His colleague Val Sears wrote in a companion piece that Pearson had already chosen the flag design.

The two articles and the publicity they received played into Opposition and Progressive Conservative leader John Diefenbaker’s hands. He accused the Liberals of being manipulative and Pearson with subverting Parliament by “personally” selecting the flag design and already informing the Queen about it — a charge the prime minister denied.

At the same time, Pearson was not to be deterred. Without conferring with his Cabinet (according to historian Norman Hillmer) he decided to speak about the flag at the Legion convention in Winnipeg, setting off a national, and frequently contentious, discussion.

Following Pearson’s well-publicized Winnipeg speech, some commentators denounced the Liberals as being anti-British. “To tamper with our traditional flag — the Canadian Ensign — at this time is mischievous and dangerous,” the editors of the Toronto Telegram claimed in a typical criticism.

Advertisement

Some Canadian historians, including Donald Creighton and WL. Morton, protested that the proposed flag was “innocuous” and that, contrary to Pearson’s belief, it would not promote national unity but merely produce “an indifferent response.”

Some members of the Liberal Cabinet were uncertain what to make of the fuss, and there were discussions about simplifying the design and featuring only one maple leaf rather than three.

Academic studies and opinion polls of the era indicated that Canadians were more or less evenly divided about adopting a new flag and retiring the Red Ensign. There is, however, no convincing polling data of French-speaking Quebecers, the group the flag was allegedly meant to appease, notes historian C.P Champion, who has written extensively on the flag debate.

The comment made in December 1964 by then University of Montreal law professor Pierre Trudeau — who within less than a year was elected to Parliament and became a member of Pearson’s government — that “French Canada did not give a tinker’s damn about the flag” was probably accurate.

Moreover, if French-speaking Quebecers did feel connected to a flag, it was the fleur-de-lys, the province’s official flag adopted in 1948 at the behest of Premier Maurice Duplessis and his Union Nationale government.

The flag debate in the House of Commons opened on June 15, 1964, with the Liberal government’s proposal to adopt the three-leafed flag on a field of white between sections of blue. The resolution included a provision to fly the Union Jack on certain occasions — an attempt to show respect for history and tradition.

If the flag resolution was to pass, the minority Liberals needed support from the other parties. Tommy Douglas of the New Democratic Party was in no rush to proceed. Real Caouette, the leader of the Ralliement des creditistes, the independent Quebec wing of the Social Credit Party of Canada, generally approved of the Liberal plan, though he regarded the maple leaf design “of British and regal inspiration” and did not support the continued use of the Union Jack.

The main obstacle in the House was Diefenbaker. Pearson’s detested Tory adversary could not be placated or convinced of the merits of the flag. To Diefenbaker, it was a disavowal of Canada’s British tradition. He demanded a referendum on the flag, something Pearson was not prepared to hold.

The Commons continued sitting all summer, but the Conservatives held firm in their opposition. By mid-September, with Parliament seriously stalemated, Pearson finally obtained Diefenbaker’s agreement to refer the flag issue to a parliamentary committee. Seven of the members were Liberal, five were Conservative, and the NDP, Social Credit, and Creditistes each had one member.

Matheson, who was appointed the committee’s chairman, was given six weeks to produce a report. Pearson was confident about the outcome. “We are going to have a new flag by Christmas,” he told one party supporter. “It’s going to be a distinctive national flag, and it will be based on this historic and proud emblem of Canada, the maple leaf.”

That prediction turned out to be correct. Yet what the flag the committee eventually endorsed was not Pearson’s preferred blue, red, and white trifoliate design. Some months earlier, Matheson had consulted with veteran and historian George F.G. Stanley, then the dean of arts at the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston, Ontario.

As Matheson recalled, Stanley “believed that simplicity was of the essence in a flag and that a single maple leaf would serve better than the three.” For his model, Stanley recommended a design based on the military college’s red and white flag, which he noted were “traditional colours for French and English Canadians.”

In time, Matheson, who had been committed to Pearson’s three-leaf design, changed his view and advocated for a flag with a single red maple leaf with two red vertical bars on a white background.

By the end of October, the choice before the parliamentary committee came down to three designs: a Union Jack and fleur-de-lys combination; Pearson’s blue, red, and white three maple leaves; and the Stanley-inspired white and red single maple leaf. When the committee vote was taken, the five Conservatives naturally assumed that the seven Liberals would vote for the Pearson pennant. And, with the intent of producing a divided result, they cast their ballots for the Stanley design.

Instead, the Liberals by mutual agreement — and with orders from Pearson, who did not want his flag to pass with a slim majority — had also decided to vote in favour of Stanley’s flag, so that it was the design most favoured by the committee and presented to Parliament.

A day before the committee’s report was tabled, however, Diefenbaker, who was furious at what had transpired, publicly dismissed the single maple leaf flag as being too close in design to the flag of Peru — which also has two vertical red bars with a coat of arms in the middle against a white background. “If we ever get that flag, we would have the Peruvians saluting it, anyway,” he sarcastically declared in a television interview,

His caustic remarks set the tone for fourteen days of rancorous debate in the House of Commons. According to Pearson, “Mr. Diefenbaker was determined to do everything possible to defeat and destroy this resolution.” The Conservatives proposed an amendment that a national plebiscite on the flag be held. When that failed, they started a prolonged filibuster.

The Liberals were rescued from this embarrassing mess on December 9 by a member of the Conservative caucus, Leon Balcer, a Quebec MP who had had enough of his own party’s time-wasting ploy. He urged the Liberals to invoke closure to halt the debate and call for the vote, a proposal endorsed by Caouette’s Creditistes.

Though Pearson was hesitant to use closure — given the bitter memories of the pipeline debate of 1956, in which a Liberal government also invoked closure, an action that was roundly condemned and had paved the way for Diefenbaker’s Conservatives to come to power — he felt he had little choice.

On December 15, a motion on closure passed 152 to 85. Diefenbaker berated the Liberals that they had given the country, “a flag by closure.” Nonetheless, two days later on December 17, 1964, at 2:15 A.M., after 270 speeches had been delivered on the subject, Canada’s flag with the single red maple leaf was declared official by a vote of 163 to 78. All but three MPs rose from their seats and sang a loud rendition of “O Canada.”

At the end of January 1965, Pearson travelled to London to witness Queen Elizabeth II sign a proclamation affirming Parliament’s decision.

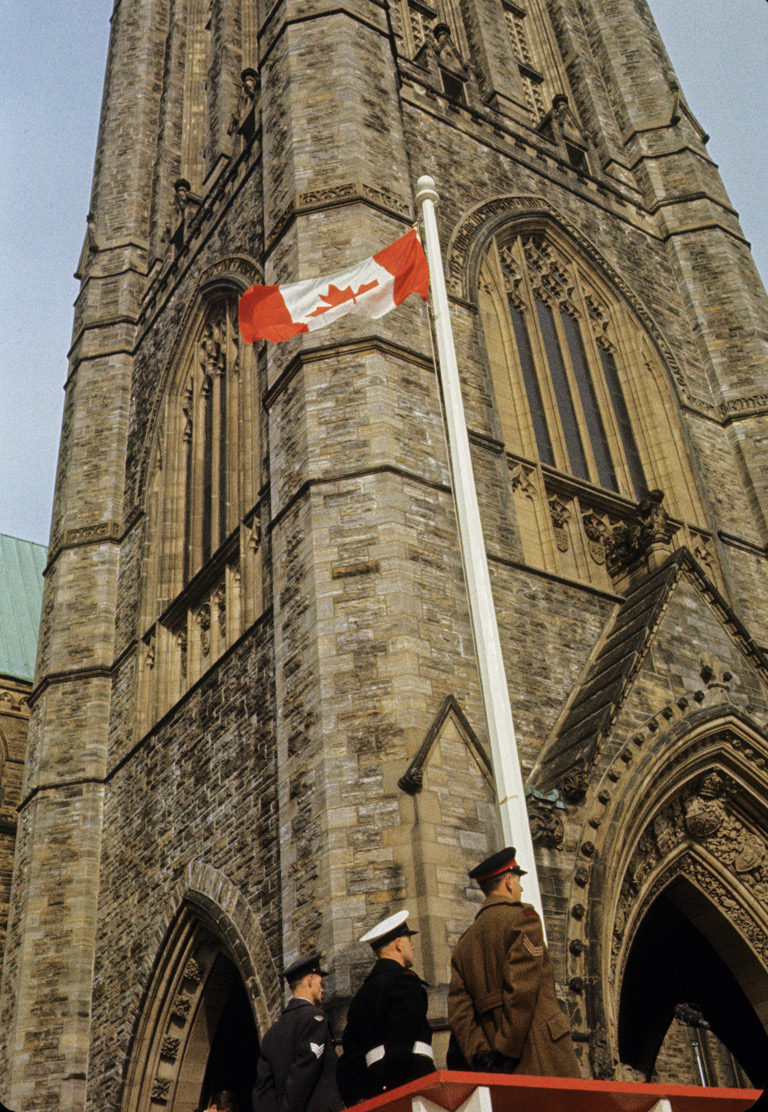

Then, back in Ottawa on February 15, at the damp and cool Flag Day ceremony on Parliament Hill in the shadow of the Peace Tower, the Red Ensign was taken down and the new Maple Leaf flag was raised with a resounding cheer from the dignitaries and the large crowd in attendance.

For Pearson, it was a proud moment — his proudest as prime minister, according to his wife Maryon — while a news photo published the next day showed Diefenbaker shedding a tear.

Did the new flag make Canada less British? Not according to historian Champion, who has convincingly shown that the choice of the maple leaf for Canada’s flag as well as the eventual choice of the colours red and white all had deep British roots.

“If it was not explicitly British in appearance, the rebranding of British scarlet, the red of the Red Ensign, as ‘gules on a Canadian pale argent,’ represented a continuing, if more subtle, Britishness — the legacy of a very British coup,” writes Champion.

This may be so. But five decades ago the adoption of the Maple Leaf flag was perceived as a step forward in Canada’s national development. As author Peter C. Newman wrote in 1964, it marked a “transfer of power from one generation to the next.”

Since its inception, the Maple Leaf flag has been carried proudly in every winter and summer Olympics since 1968. It has been highlighted on sports uniforms, worn on suit lapels, and displayed on the backpacks of generations of Canadians trekking across the world.

Fittingly, when Pearson passed away in 1972, his coffin was draped with the red Maple Leaf flag. And, just as fittingly, when Diefenbaker died six years later, his casket was covered with two flags — a Maple Leaf and a Red Ensign — sewn together.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk bow tie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. This bow tie was inspired by Pierre Berton, inaugural winner of the Governor General's History Award for Popular Media: The Pierre Berton Award, presented by Canada's History Society. Self-tie with adjustments for neck size. Please note: these are not pre-tied.

Made exclusively for Canada's History.