Reluctant Union

It didn’t. Perhaps Newfoundlanders were exhausted by the fevers of the two referendum campaigns that led up to the vote. Or perhaps the politics of some sixty years ago had a grace and consent that the politics of today has long forgotten. Either way, one of the most remarkable considerations of Confederation with Canada, once achieved, was how little turmoil or resentment followed that transition, mandated as it was on one of the closest votes on the profoundest possible question ever submitted to the Newfoundland population.

I take that as a starting point for a survey of Newfoundland and Labrador sixty years after the (for us) epochal event. Confederation settled in with astonishing ease. There were, of course, some pockets of resentment. A few heroes of the anti-Confederate movement were durable in their bitterness and disappointment. And, as in any immensely emotive and close contest, there was a predictable after-cloud of suspicion that the result had been “manipulated,” that the greater forces of Great Britain and the Canadian government had arranged the result from the beginning. A few bad novels and one bad movie have mined the minimum vitality of that theory. But overall, Confederation, having been achieved, was accepted (local Oliver Stones notwithstanding) and in the main celebrated.

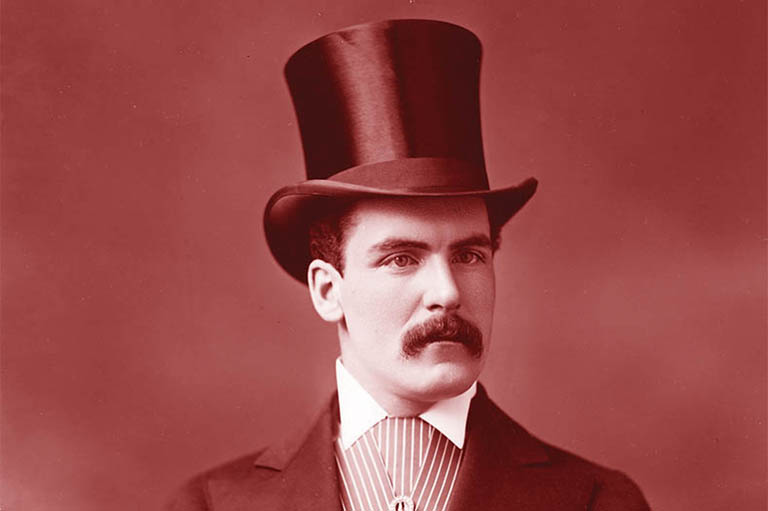

Some of this was, emphatically, a consequence of the formidable and relentless persuasions of Smallwood after Confederation. Every man is a hero in his own drama, and in the theatrics of ego Smallwood was a playwright of the highest order.

But there were reasons why Confederation settled in that went beyond Smallwood’s striving for a large page in the history books. And they were, in fact, real history.

Newfoundland was poor, really poor, before Confederation. By any index or standard the people of Newfoundland had it spectacularly hard. The stories of life in Newfoundland in any decade from 1900 are horrifying. Read some account of Wilfred Grenfell’s mission in Labrador. Or read Peter Neary’s fascinating edition of the letters of a colonial administrator from the 1930s, White Tie and Decorations. Every child in the 1950s in Newfoundland grew up on stories from parents or grandparents telling of hardships, isolation, poverty of the grimmest kind, poor health, early mortality.

Hard times form character; the axiom is undeniable. And out of hard times, compounded by isolation, a real character — the Newfoundland character: stoic, humourous, selfless, inventive in speech and song — emerged or evolved. But at what price? At what cost of opportunities fore-shorn, potential amputated?

Who else would have lasted here? Who else could have made out of the constant scramble for existence, signposted by calamity and deprivation (disasters at sea, slaughter in war are the terrible “achievements” of Newfoundland’s collective experience) such a genuinely rich, enfolding, even warm way of life?

The great common voice of Newfoundland is in those questions. We had learned to cherish our hard interactions with a hard place, and worked an alchemy that perhaps few other peoples have, of transmuting what should be merely a record of hanging on to a triumph of community Indeed, it goes deeper or further than that. It is the central paradox of Newfoundland history that the harder it was the more we “liked” Newfoundland. It is all caught in an almost proverbial tag for Newfoundland: this “marvellous terrible place.”

Confederation was the event that broke the miserable chain. We yoked with the larger continent, entered a fully twentieth-century nation, and within a decade were taken up by the great systems and institutions that underpin modern Western society. “No longer alone” is the motto of post-Confederation Newfoundland. But always at the back of every Newfoundland mind, even sixty years on, is the wondering thought: Was the trade a good one? Not as the simple equation: Did we barter our “distinctness” for a better life of goods and services? But did we secure the better life at the expense of some greater largeness of being? To phrase the point this way is to invite, perhaps, an easy mockery.

By standard accounting, there can be no debate at all about Confederation. We are better off for it. It may be that the generation born since Confederation is the very first one in Newfoundland, since Newfoundland was a place name on the early maps, that has had the means — schools, hospitals, communications, a standard of living above subsistence — to realize its potential. The first generation for which choice replaced necessity as the essential dynamic for a true majority of Newfoundlanders.

This is a very compelling recommendation for Confederation, and it is probably the enduring practical one. But every major choice is also a foreclosure; the embrace of Confederation in 1949 was equally a farewell. It was a farewell to a singular and profoundly textured strain of character and identity. Newfoundland life, for all of the deprivations and abrasions of history, was also marked by its intensity, by an abundance of response, a relish in living here. The vigour, inventiveness, humour, and charge of Newfoundland culture has been for almost all of its existence one of the strange miracles of this continent.

Confederation was a shield against the wind, but for some Newfoundlanders (I think I’m one of them) it will always be tinged (in no mean or bitter sense) with the rueful flavour of a resignation — that our winding, odd, precarious, difficult, perplexing journey since Cabot’s landfall had to close. As I noted at the very beginning of this note, there was remarkably little turbulence after the choice had been made. Newfoundlanders “became” Canadians — a remarkable transition when it’s thought about — almost overnight.

But even sixty years on there is still the quiet thought — perhaps instinct is the better term — that in the exchange, made necessary by history and endorsed by every measure of practicality, we may have let slip something of the elusive scant glory caught in the paradox of “this marvellous, terrible place.”

A short history of government in Newfoundland

Law and order at last: A couple of thousand year-round residents of Newfoundland were governed by the arbitrary rules of fishing admirals until 1729, when British naval Captain Henry Osborne established constables and justices of the peace.

Colonial status: After long being regarded by Britain as a fishing base, not a colony, Newfoundland was in 1824 granted a civilian governor and an appointed legislative council. In 1832, an elected council began sitting with the appointed body.

Democracy: A popular vote in favour of responsible government led to Philip Francis Little becoming Newfoundland’s first prime minister in 1855. The colony became a dominion in 1907.

Early attempts to join Canada: Union with Canada was considered in the early 1860s but the public quashed the idea in the 1869 election. The notion was revisited in 1895 after a series of disasters left Newfoundland destitute, but talks went nowhere.

Government by commission: The Great Depression bankrupted Newfoundland and people faced starvation. Confronted with rising social unrest, the Newfoundland government approached Britain for aid. As a result, the elected government was replaced with an appointed commission, which governed from 1934 to 1949.

The tenth province: With economic stability restored, voters in 1948 chose between commission government, self-government, or union with Canada. Union won by fifty-two percent on a second referendum and Joseph Smallwood became the first premier in 1949.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement