Personae Non Gratae

Educator Rev. Adolphus Egerton Ryerson is among seven prominent Canadians who will no longer be recognized with historic plaques as the result of a federal review.

Historic Sites and Monuments Board plaques recognizing the seven have been permanently removed due to their connection with residential schools or to other policies that impacted Indigenous people, Parks Canada announced in late August.

“For each of the designations, the Board recommended that no new plaque be installed, as the limited text of a plaque does not allow for adequately communicating this complex history,” the federal agency stated. The iconic bronze plaques are usually attached to stone cairns and are limited to 642 characters each.

While the seven will keep their designations as national historic persons, their reasons for being selected have been updated to include their roles in government policies that harmed Indigenous peoples. In all, more than two hundred plaques have been under review since 2019 for content deemed outdated or offensive.

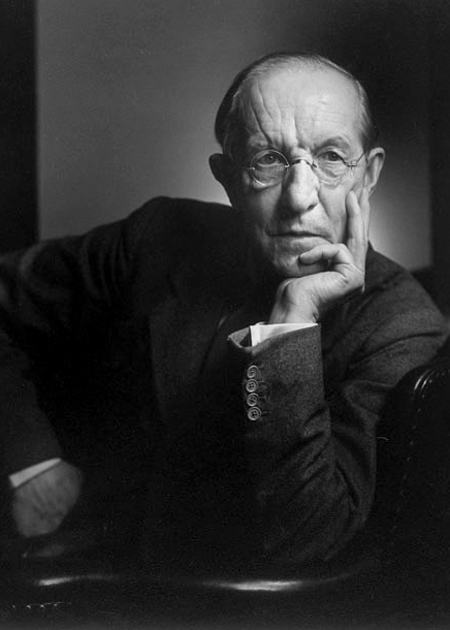

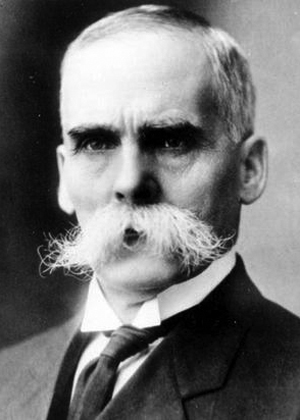

Duncan Campbell Scott (1862–1947)

Year of designation: 1948

In his day, Scott was widely known and celebrated as a poet and writer. He was also the chief federal government minister responsible for expanding and administering Canada’s residential school system and the Indian Act.

Nicholas Davin (1843–1901)

Year of designation: 1947

Davin was a journalist, poet, orator, and prominent Western politician. As the author of the Davin Report, he recommended removing Indigenous children from their families and stripping them of their cultures.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

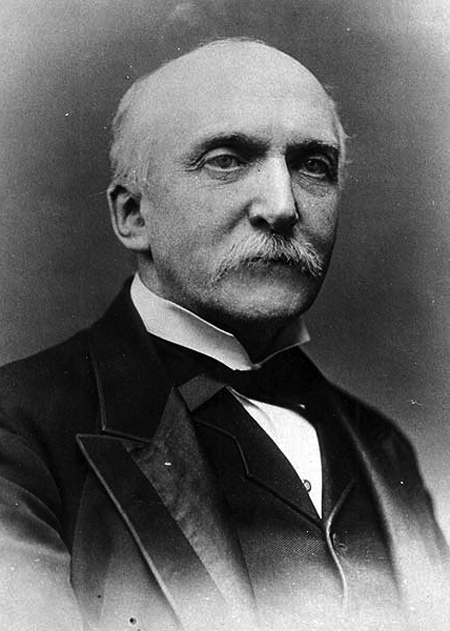

Hector-Louis Langevin (1826–1906)

Year of designation: 1938

A Father of Confederation and a defender of Quebec’s interests, Langevin helped to draft the seventy-two resolutions of the British North America Act. But, as minister of public works, he supported aggressive assimilation policies for Indigenous children and his government’s plans to establish three industrial residential schools in the Northwest.

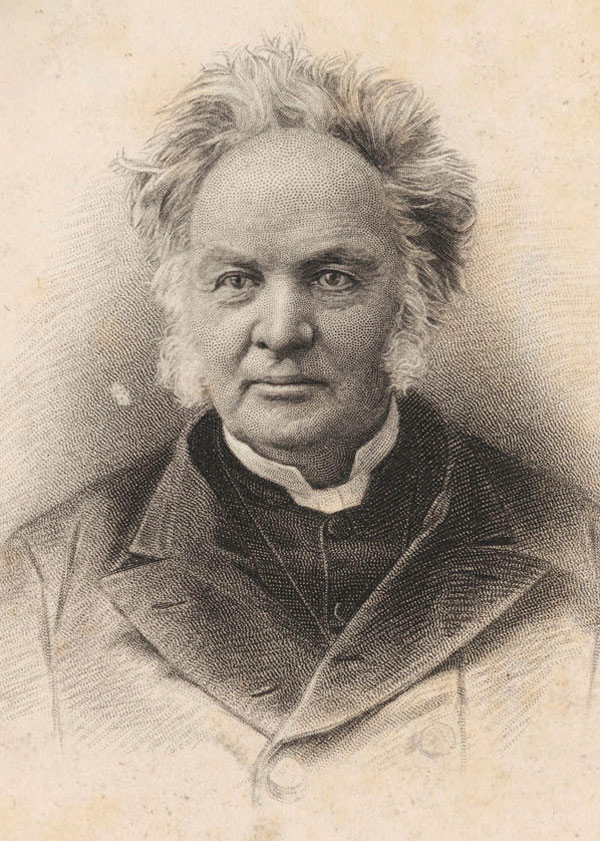

Rev. Adolphus Egerton Ryerson (1803–82)

Year of designation: 1934

As chief superintendent of education for Upper Canada, Ryerson standardized the education system, introducing free elementary schooling. He opposed racially and religiously segregated schools, but bowed to public pressure to allow them. A report he wrote for the federal government was used to support the residential school system.

Advertisement

Joseph William Trutch (1826–1904)

Year of designation: 1975

Trutch was a British-born engineer, surveyor, and politician. As British Columbia’s chief commissioner of lands and works, he reduced the size of existing reserve lands, denied Indigenous title, and continued the provincial policy of not entering into Treaties with First Nations.

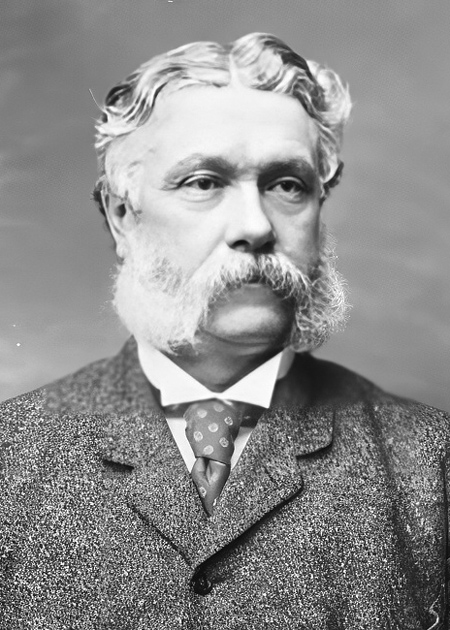

Edgar Dewdney (1835–1916)

Year of designation: 1975

Dewdney was a surveyor, politician, and Indian commissioner in the Northwest. As commissioner, Dewdney withheld food from starving Indigenous people to coerce them onto reserves. He also established a pass system limiting off-reserve travel by First Nations people and helped initiate and shape the residential school system.

Frank Oliver (1853–1933)

Year of designation: 1947

A Western journalist and politician, Oliver successfully advocated the forced surrender of First Nations reserve land and personally benefited by acquiring some of the relinquished lands. As federal minister of the interior, Oliver restricted Black and Asian immigration and oversaw the expansion of residential schools.

Canada's History magazine was established in 1920 as The Beaver, a Journal of Progress. In its early years, the magazine focused on Canada's fur trade and life in Northern Canada. While Indigenous people were pictured in the magazine, they were rarely identified, and their stories were told by settlers. Today, Canada's History is raising the voices of First Nations, Métis and Inuit by sharing the stories of their past in their own words.

If you believe that stories of Canada’s Indigenous history should be more widely known, help us do more. Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share Indigenous stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!