It's My Right!

October 28, 1972, Edmonton

Eric held up a jean jacket decorated with bright yellow happy face. “Look! Only a dollar.”

Marianne raised one eyebrow. “It’s kind of cool. Unlike you.”

The woman behind the table piled with clothes, dishes and toys tried not to laugh. “You should be nicer to your little brother, even if he’s taller than you are.”

“I’m smarter, too, Mrs. Nakamura,” said Eric as he handed her a dollar bill and slipped the jean jacket on.

“Oh, please!” Marianne said. “I’m 21. You’re still in high school.”

“But I can vote on Monday just like you can,” Eric retorted.

Marianne was looking through a box full of records. “Big deal,” she said absent-mindedly. “Oh, wow!” She held up her find. “The Guess Who!”

Mrs. Nakamura looked serious.

“Back up, young lady. Voting is a VERY big deal! My family has only been allowed to vote in Canada a little longer than you’ve been alive.”

Eric and Marianne stared at her in shock as a man with long black hair looked up and nodded. “That’s around the time Inuit were able to vote. Took Canada even longer to allow Cree people like me. I’m Dan, by the way. Just moved in.” He reached out to shake hands.

“That’s terrible!” Eric’s face showed his disbelief. “Not that you moved in,” he added quickly. “The voting thing.”

“Of course, some of us didn’t want anything to do with elections,” Dan added. “Still don’t. Lots of us just want to govern ourselves.”

He picked up a big ceramic statue of a dog. “What do you want for this?” he asked Mrs. Nakamura.

“Please — just take it!” she said with a laugh. “I’ll be so happy not to have to dust it!”

“Thanks!” Dan said. “Nice to meet you all. Now for some butter tarts!” He tucked the statue under his arm and headed over to the bake sale table.

Mrs. Nakamura sighed. “You don’t understand how lucky you are, Marianne. A lot of people in Canada haven’t been able to vote until very recently. That’s why I care about it so much.”

Her mind seemed to be else whereas she arranged, then rearranged some glass vases. “My family is from Japan, but I was born here. I’m Canadian, but that didn’t matter. The government said we didn’t deserve a voice in our own country’s elections.”

She shook her head. “It wasn’t just us, or people like Dan, or people whose families came from China or India.Your grandmother once told me how much it upset her that for the longest time, your grandfather could vote and she couldn’t.”

Marianne’s face went red, and then white. “I . . . I had no idea. I always thought election talk was so boring.

But I can’t imagine Eric being allowed to vote and not me.”

Her dad wandered up. “I have strict instructions not to buy any more stuff until we sell all of ours.” He waved back at his wife.

Eric piped up. “Hey Dad — do you always vote?”

“You bet I do!” his father replied firmly. “Your grampa always told me that in the country where he grew up, people died fighting for that right.” He nodded at his neighbour. “Including many Canadians from Chinese and Japanese backgrounds. A lot of people in the world have no say at all in who their government is or what it does. But we do.”

Mrs. Nakamura caught Eric and Marianne glancing at each other and smiled. “So . . .?”

Marianne looked doubtful. “I still don’t see how my one vote makes any difference.”

“Well, what do you care about?” her dad asked. “Now, what if everyone else who cared about the same things also thought their vote didn’t matter so they didn’t bother to go to the polls on

Monday?”

Marianne threw up her hands. “Okay, okay! Voting matters. I get it!”

“It’s also a big responsibility,” Mrs. Nakamura added. “As far as I’m concerned, if you don’t vote, you’d better not complain about the election results.”

Eric stood up tall. “I’m going to vote! After all, it’s my right.”

“And it’s my right, too!” Marianne declared.

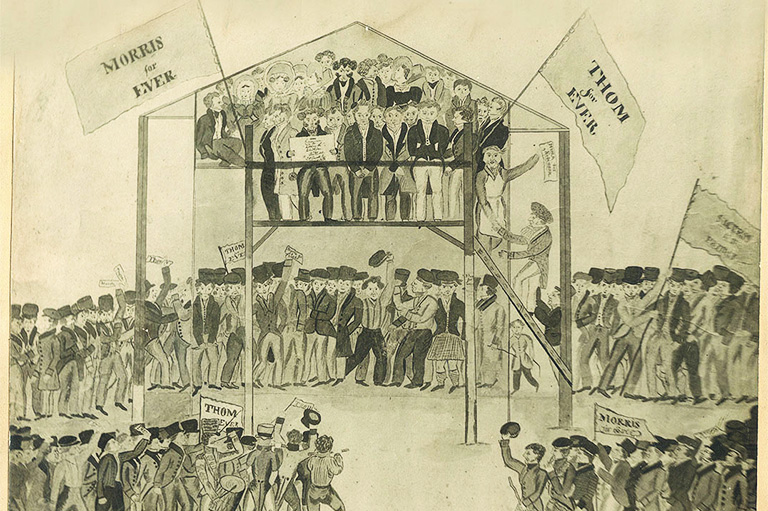

The characters in this story aren’t real, but the 1972 Canadian election was the first after the voting age dropped from 21 to 18. There have been many changes to voting rights over Canada’s history. At first, only men who were wealthy enough could vote in federal elections.

Before confederation, some women property-owners voted. Black or Métis men weren’t barred, but few were wealthy enough to qualify. The only way First Nations men could vote was to give up their treaty rights. In 1918, after decades of fighting for their rights, Canadian women were finally allowed to vote in national elections. The 1934 Dominion Franchise Act set national rules, but there were still many groups of people who were barred from voting.

A group of Canadians of Japanese heritage travelled to Ottawa in 1936 to explain to a House of Commons committee why they should have the right to vote.They were turned down. Canadians of Chinese, Japanese and east Indian descent were only able to vote in 1948. Religious groups like Mennonites, Doukhobors and Hutterites who opposed serving in the military had the vote taken away during the two world wars. And it wasn’t until 1950 that Inuit could vote, although ballot boxes often weren’t even sent to their communities. In 1960 First Nations people in Canada could finally vote nationally without having to give up treaty rights.

Among the more recent groups to get the right to vote in federal elections were people with intellectual disabilities (1993) and prisoners (2004).

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement