Hunting Lincoln’s Killer

The bodies and blood were everywhere, blanketing the Virginia hills and the banks of the Bull Run River on that beautiful summer day in 1861. U.S. President Abraham Lincoln’s Union forces were being massacred.

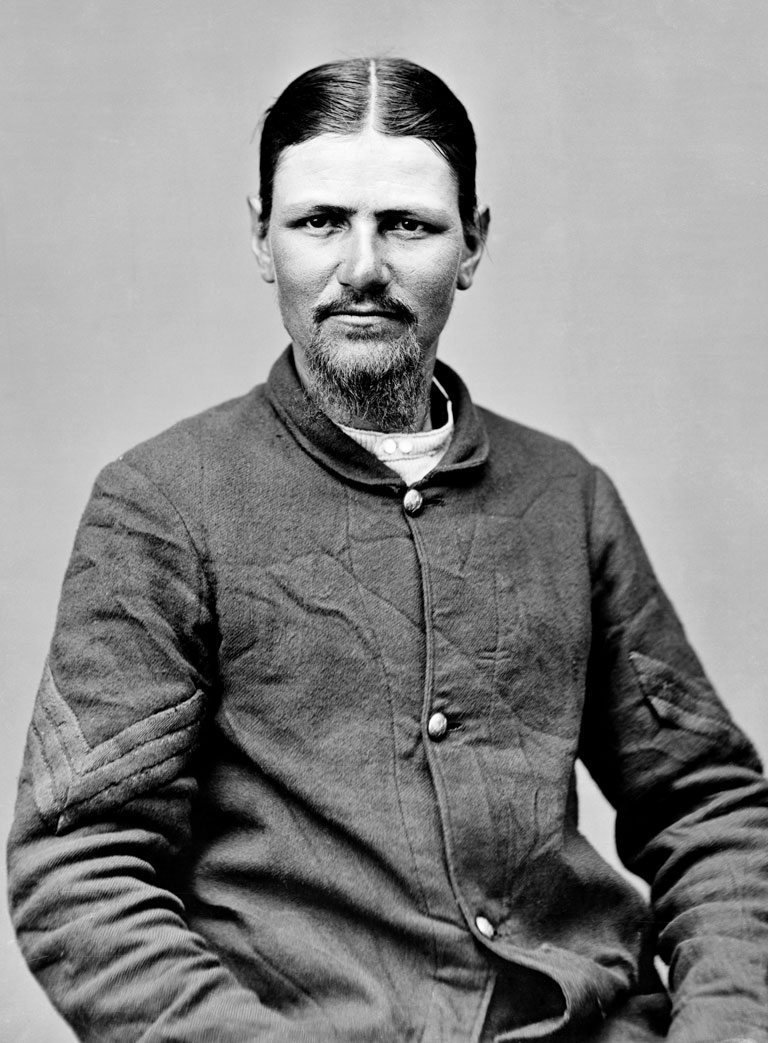

“We waded in great confusion,” recalled a twenty-three-year-old soldier named Edward P. Doherty. “We were immediately ordered to fall back and lie down, as the discharge from the enemy’s battery was severe.”

The Battle of Bull Run — the first major battle of the American Civil War — unfolded on July 21, 1861, just forty kilometres southwest of Washington, D.C. Confidence of victory was so high among Union supporters that a large crowd of spectators, including several members of the U.S. Congress, gathered nearby, carrying picnic baskets and opera glasses.

It turned into a rout. “Legs, arms and bodies are crushed and broken as if smitten by thunder-bolts; the ground is crimson with blood,” recalled one of Doherty’s fellow soldiers. A desperate Doherty dragged some of his wounded comrades to a nearby church that was serving as a field hospital, then he dashed across the battlefield to rejoin what he supposed was his regiment. He was badly mistaken: They were enemy Confederates. “The cavalry galloped up and arrested me,” he wrote in a gripping account published in the New York Times.

Doherty was just one of thirteen hundred missing or captured Union soldiers that day; another fifteen hundred perished. What made him different was that he was Canadian. This was not his country, but, like many other Canadians, he made it his war.

For four years the American Civil War raged between the Northern Union and the Southern Confederate armies, claiming more than six hundred thousand lives. On that summer morning in 1861, Edward Doherty could never have imagined what his final and fateful mission in that war would be.

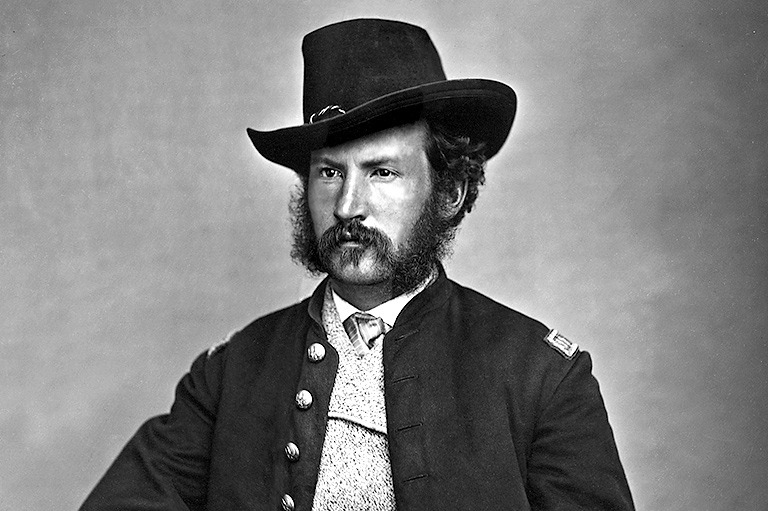

Little is recorded about Doherty’s early life except a handwritten entry in a church registry that shows he was born into a family of Irish immigrants in 1838 in Wickham, a small town in what was then called Canada East, not far from Montreal. Doherty moved to that city to go to school, graduated from college, and studied law with a local firm.

By 1861, Doherty found himself working in New York City. On April 20, a week after the Civil War broke out, he ran into some companions who had just enlisted. “I met a number of my friends who were members of the 71st regiment — who, after some parley, induced me to become a member of their corps,” he recounted in a remarkably detailed series of letters printed in the Montreal Gazette under the title “Letter from the Seat of the War. From a Montrealer in the U.S. Army.”

Just like that, he was a private in Company A of the Seventy-First New York Volunteers. Doherty never elaborated on his reasons for enlisting so quickly, though his military diaries revealed a young man’s thrill at the prospect of stirring battles and “gallant soldiers.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Doherty and the rest of his regiment were quickly dispatched to Washington, where the Northern troops were gathering. The president himself came by to visit the new recruits soon after: “On Sunday, we were honored by a visit and a how do you do shake hands,” Doherty reported in the Montreal Gazette.

Soon after, the men of the Seventy-First Regiment found themselves plunged into the nightmare that was Bull Run. After the brief but bloody battle, the victorious Confederates confined Doherty and other prisoners in the nearby church that had been turned into a field hospital. It became a sort of tomb for the dying and a dungeon for the living. “During the confusion, I managed to conceal myself under a blanket which was saturated with blood,” he recounted in the New York Times. “They left me, supposing I was wounded.” All through the night, Doherty tried to ease the suffering of those around him, but by the next morning thirty-two of his fallen comrades had died.

The healthier prisoners were being marched away to Richmond, Virginia. Doherty had no intention of being forced deeper into enemy territory, much less of being left behind to die. He and two other captured soldiers made a break for it. They snuck past the guard, ran all night and for seven days more across railroad tracks, fields, and forests, before they finally made it back to a Union camp.

After a warm supper and a good night’s sleep, Doherty insisted on riding back to Bull Run to see where so many of his comrades had fallen. “I visited the field of battle on horseback,” Doherty recalled. “I saw there numbers of our comrades, unburied.” As he looked over the hills littered with rotting bodies, it was not only the blood or the disfigured faces and torn limbs that struck him. “The smell was offensive,” he remembered.

Doherty’s bravery helped him to move up the ranks. His military record was full of praise from his superior officers. “His reputation for gallantry in the field as admired by his brother officers is second to no one in the service,” said one commander. Even his foes had strikingly similar praise for the Canadian. One unnamed Confederate in Doherty’s military files described him as “that gallant officer.”

By September 1863, the war had dragged on for two years with no sign of victory for either side. Doherty arrived in Washington, joining the Sixteenth New York Cavalry as a first lieutenant. His new regiment was handed the important assignment of “covering the Defences of Washington, D.C., and operating against guerrillas,” according to his military records. Their job was to protect the city, though not the president.

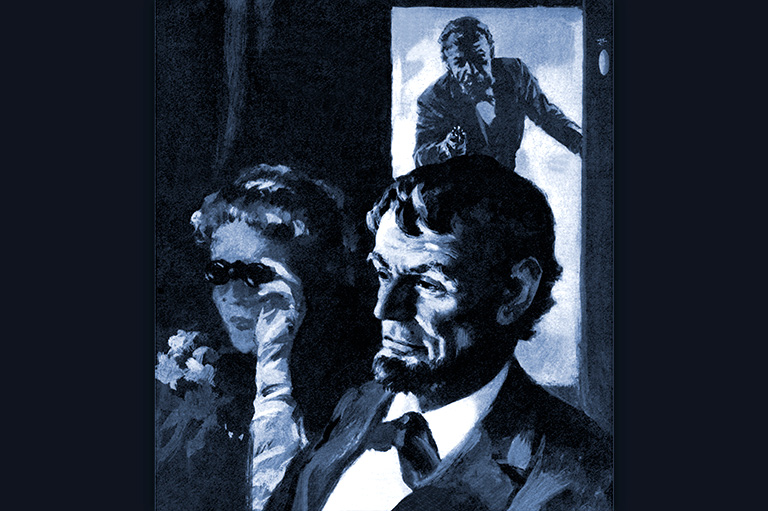

Two more years of heavy fighting finally gave Abraham Lincoln his victory against the Confederacy, though not the unity of the “house divided” he had warned about in a famous speech three years prior to the Civil War’s outbreak. Hatred ran deep in the South for the president who — through his Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, and through the ultimate victory of his Union Army — had freed America’s slaves. Few were more enraged than John Wilkes Booth — one of the country’s most famous actors and most ferocious Southern sympathizers. In a letter justifying his stance, he had proudly proclaimed that “this country was formed for the white, not for the black man.”

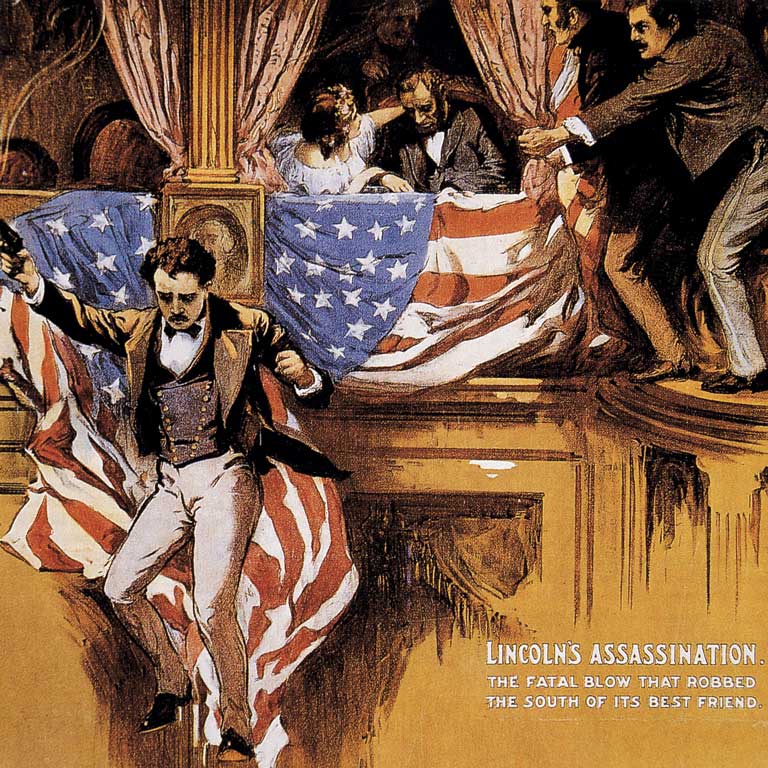

On April 14, 1865, while Lincoln was celebrating the end of the war by attending a play at Ford’s Theatre, Booth snuck into the presidential box and fired a single bullet into the back of the president’s head. The assassin dashed away on horseback in the dark of night, crossing into Maryland where he met up with an accomplice named David Herold.

Doherty never recorded his thoughts on the slaying, but he must have been as shaken as everyone else in Washington. Ten days later, he was sitting on a bench in Lafayette Park across from the White House. Amidst the gloom and grief that shrouded the city, it was a rare moment of rest for the Union Army lieutenant. “It was my day off and I was rejoicing my soul in the bright rays of spring sun,” he later recalled in a magazine interview.

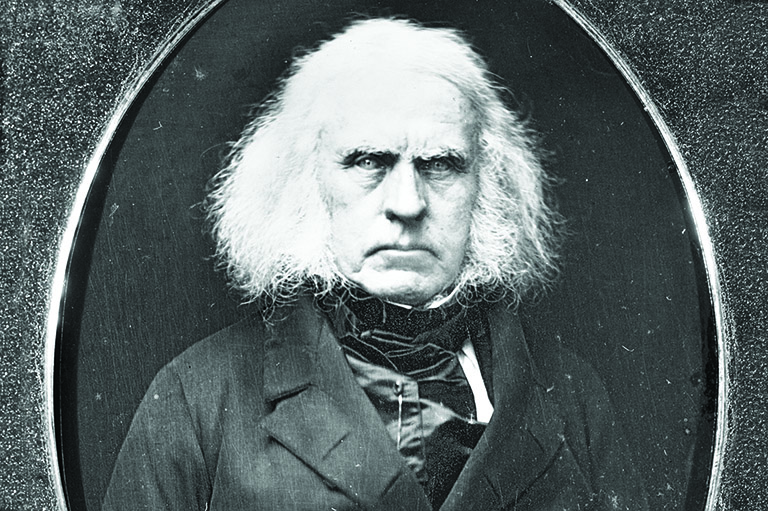

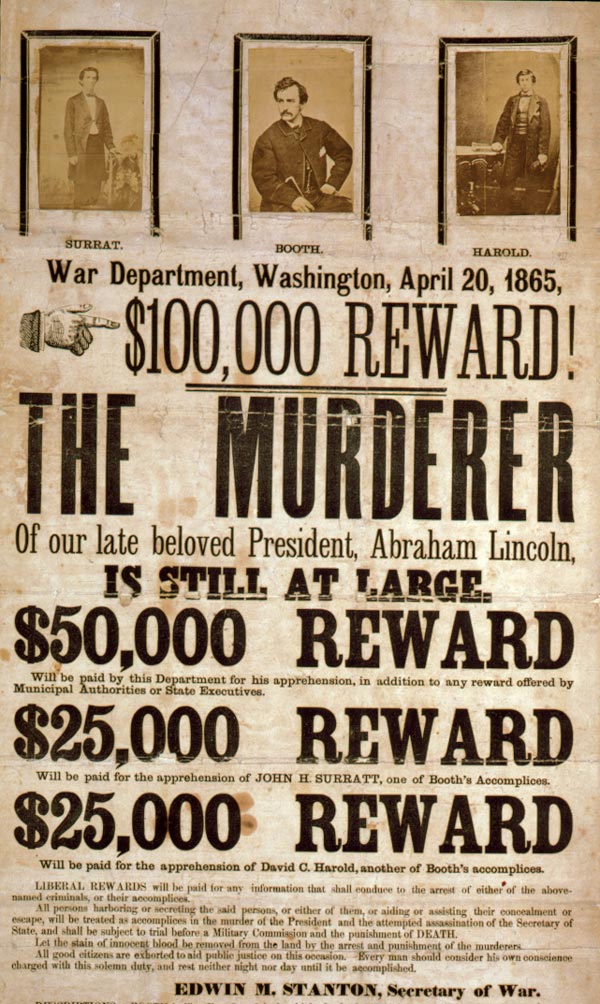

His respite in the park that day was interrupted when a messenger approached with urgent orders. The specifics of his new mission were not spelled out; all Doherty knew was that his commander in the Sixteenth New York Cavalry had been told to find “a reliable and discreet commissioned officer” and twenty-five men and to equip them with three days rations. Doherty rushed back to his barracks and sounded the call to his men for “boots and saddles.” He then made his way to the War Department, where he was told to report to Lafayette Curry Baker. At the time there was no FBI or Secret Service. Baker, a controversial figure with a reputation for brutality and corruption who headed a private firm known as the National Detective Agency, had been tasked by a desperate government to oversee the investigation into the assassination.

“Colonel Baker handed me photographs,” Doherty recalled. They were pictures of Booth and his accomplice, Herold. Doherty suddenly grasped the gravity of his assignment: He had been charged with hunting down the accused conspirators behind the murder of Abraham Lincoln.

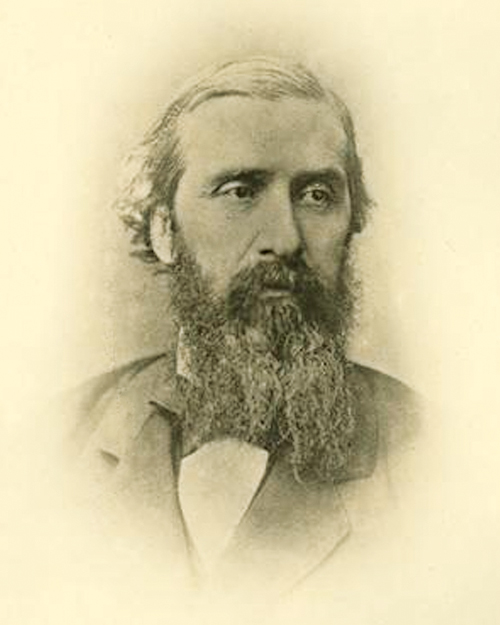

Lafayette Baker appointed two of his own detectives to accompany Doherty: his cousin Luther Baker and a former cavalry officer named Everton Conger. No one disputed that it was Doherty who was in charge of the military regiment. But jealousy and rivalry quickly set in between the civilian detectives and Doherty. Later, they would each claim that they had played the major role in the events that would follow.

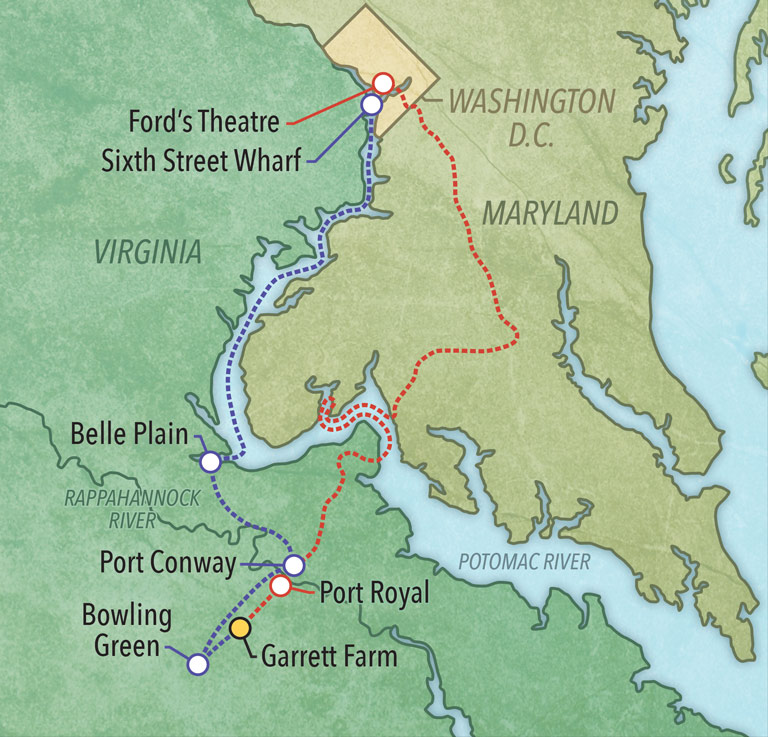

The authorities had received information that Lincoln’s killer was hiding out somewhere between the Potomac River, which divides Maryland and Virginia, and the Rappahannock River, further to the southwest. Doherty led the search party through the night, first by ferry and then on horseback, south down the Potomac River and into Virginia. Arriving on the shores of the Rappahannock River late in the afternoon of April 25, they approached a fisherman who ran a ferry and showed him pictures of the fugitives. He recognized Herold and Booth, explaining that he had helped them and some Confederate soldiers to cross the river the day before. “We concluded that we were on their track,” Doherty recalled.

A vital clue came when the fisherman’s wife disclosed that Willie Jett, one of the three Confederate soldiers who had helped Booth, would likely be visiting his girlfriend at a hotel at Bowling Green, just twenty-five kilometres away.

The searchers dashed to the hotel and confronted Jett, who initially denied knowing anything about Booth. Doherty was having none of it. “We took Jett down stairs and informed him our business, telling him that if he did not forthwith inform us where the men were he should suffer; that no parley would be taken,” Doherty recounted. Jett confessed to the search party that he had decided it would be best to hide Booth at a nearby farm owned by a man named Richard Garrett.

That, at least, was Doherty’s account in the lengthy official report that he submitted to the military on April 29, 1865. In his telling, he played the lead role in tracking down Booth and Herold and in the confrontation that followed — although Baker and Conger, in their versions, made themselves the centre of the verbal exchanges and action.

Doherty’s account — told in his military report and in later newspaper interviews — continued with the arrival of his party at the Garrett farm in the pitch-black, early morning hours of Wednesday, April 26. Booth had been on the run for twelve days, and now he was cornered. Doherty’s men and the detectives surrounded the barn on the property where the Garretts said Booth was sleeping. Doherty noticed a large crack on one side and stationed Sergeant Boston Corbett to stand watch at that corner of the barn.

“Booth all this time was very defiant and refused to surrender,” Doherty recounted in his military report. “Considerable conversation now took place between myself, Booth, and the detectives. We threatened to burn the barn if he did not surrender.”

Booth then offered to send out his accomplice, Herold. “Oh, Captain, there is a man here who wants to surrender awful bad,” the assassin announced. Herold stuck his hands out through the barn door. Doherty grabbed Herold’s wrists and pulled him out of the barn. Then he had his men secure Herold with some rope.

But inside the barn the famous actor was not through performing. “I own all the arms, and intend to use them on you gentlemen,” the assassin declared. The search party carried out its threat and began to light a fire around the building. Booth stayed put as the fire spread. A single gunshot added to the confusion as the flames crackled in the burning barn.

Doherty, thinking at first that Booth had shot himself, raced into the burning building with the others to grab Booth. “He was dazed for a moment and his eyes bore that piteous expression characteristic of a hunted deer,” Doherty later recalled in an interview with the Brooklyn Citizen. “He bent forward as if to make a spring and, raising his right hand, ran his finger through his heavy hair as if collecting his thoughts.” Then Booth slumped down and collapsed onto the floor of the barn.

It was not Booth who had fired what would turn out to be the fatal shot but Corbett, the man Doherty had stationed at the corner of the barn. “Corbett … seeing by the igniting hay that Booth was leveling his carbine at either Herold or myself, fired, to disable him in the arm,” Doherty recounted later in the popular Century magazine. “But Booth making a sudden move, the aim erred, and the bullet struck Booth in the back of the head, about an inch below the spot where his shot had entered the head of Mr. Lincoln.”

The soldiers gathered around the dying assassin. One put his hand under Booth’s sagging head, and then they carried out Booth’s limp body from the flames of the barn to the front porch of the Garrett home. “Booth asked me by signs to raise his hands,” Doherty recalled. “I lifted them up and he gasped, ‘Useless! Useless!’”

They tried to offer Booth water and brandy, but he could not swallow anything, as he drifted in and out of consciousness. Doherty sent for a doctor, but there was nothing to be done. “At seven o’clock Booth breathed his last.”

On the Garrett porch, Doherty and the team proceeded to go through the dead man’s pockets. They found a diary, a large bowie knife, two pistols, a compass, and a banknote from Canada for sixty pounds. The banknote in Booth’s pocket was money he had withdrawn from an Ontario Bank branch in Montreal during a trip to Canada six months earlier. The irony was that Montreal — where Doherty had lived and studied before heading to the United States — had become a nest of Confederate spies and sympathizers during the war. Booth did more than banking there. He met with Southern agents and obtained letters of introduction to Confederates in Maryland that he would use to further his plots and to pull off his escape after the assassination.

Doherty had hunted down the president’s killer across two states. Now he had a corpse to get back to Washington. He did so with surprising tenderness and care, according to his account in Century. “I took a saddle blanket off my horse, and, borrowing a darning needle from Miss Garrett, sewed his body in it.”

For Edward Doherty, that was the end of the hunt for Lincoln’s murderer. But it was just the beginning of his fight to secure a reward and, even more importantly, his reputation.

A nasty battle was brewing over the reward of more than $100,000 that had been offered for the capture of Booth and his accomplices. In early May 1865, Doherty wrote to the army’s chief of staff, submitting the names of the soldiers who had served under him with a simple message: “My command and myself claim the honor of having effected the capture of the assassins and we respectfully ask that the reward offered be properly distributed where it belongs.” He sent the army’s top brass affidavits from no fewer than thirteen of his men. One after the other, they confirmed the leadership role Doherty had played in the hunt.

But Lafayette Baker and his underlings, Conger and Luther Baker, did not want Doherty and his men to get the glory or the cash. In late December 1865, they lobbied Secretary of War Edwin Stanton in an account filled with exaggerations, omissions, and outright lies — even claiming at one point that Doherty had hidden under a shed, a fabrication unsupported by the testimony of any of the eyewitnesses. In their version of events, Lafayette Baker had masterminded the entire hunt from his office in Washington. Never one to be modest, Lafayette Baker concluded — despite the facts that he had stayed in Washington, uncovered no clues, and was nowhere near the chase — that he was in effect the one who “apprehended both Booth and Harrold [sic] … and is entitled to the reward primarily.”

Stanton appointed a special judicial committee to sort through the deluge of claims, and its report in April 1866 made clear Doherty’s central role in the capture of Lincoln’s assassin: “The expedition was imminently of a military character. Its special duty was to scout through a considerable region of country lately within the enemy’s lines, and inhabited by a class hostile to the government, who would readily aid in the escape or concealment of the fugitives, and who could be overawed and compelled to surrender them, or give information in regard to their route, by military force alone. The military element of the expedition is, therefore, believed to have been that which was essential to its success. … Lieutenant Doherty is shown to have acted and been recognized as the commander of the expedition.” As such, he was worthy of the largest share of the reward — $7,500 (worth about $137,000 today) — about twice as much as Baker and each of his detectives was allotted. Enraged, Doherty’s rivals used their political connections in Congress to engineer a hearing into the “fairness and propriety” of the reward payments.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Giles Waldo Hotchkiss, a New York congressman, opened the proceedings with a full-frontal attack. “I believe Lieutenant Doherty was a downright coward in the expedition,” he said, repeating the slanderous stories spread by Lafayette Baker. “Doherty stayed under a shed, and no power could drive him out of it,” Hotchkiss contended, while his frightened men were “lying around under the apple trees and elsewhere.” The committee voted to give Lafayette Baker the biggest share of the reward and slashed Doherty’s payment.

Fortunately, some justice was restored when the report was put to a vote in the full House of Representatives. Lafayette Baker — whose machinations and lies had also earned him plenty of political enemies — saw his bounty massively slashed. Doherty had his reward pushed back up to $5,250. It was a messy end to an ugly affair.

Worse than any squabble over money, Doherty had been slandered in Congress, the most public forum in the country. Doherty voiced his outrage in a letter to the New York Times. “I cannot remain quiet under such a charge, affecting my character as a soldier and my conduct as an officer,” he declared.

“Chance has connected my name with a great historical event,” wrote the Canadian who took up the Union cause, “and I simply desire that the army with whom I served, and the people for whom I fought, should know that in the performance of my duty, I was not a laggard and a coward.”

At least within the army, Doherty’s courage was not questioned. He was transferred to the Fifth U.S. Cavalry and sent to Kansas and Colorado to help the U.S. Army drive the Cheyenne out of their lands in a series of raids and massacres known as the Republican River Expedition. During one particularly bloody battle, at least fifty Cheyenne fighters were surrounded and slaughtered. It was a tragic twist of fate that the Canadian who had fought in Lincoln’s army in a war that ended slavery would end up helping that army in its ugly war of extermination of Indigenous peoples.

In any event, Doherty’s military days were coming to an end. Trouble inside the ranks began brewing for him by 1868, according to author James Carson, who carefully chronicled the history of Doherty’s cavalry regiment. It started with complaints that Doherty had meted out improper punishments to enlisted men under his command. An army investigation found no fault and accepted Doherty’s defence that he was harsh but fair. But then Doherty was accused of going to the house of a “common, public prostitute” in uniform; there were reports of unpaid debts and a serious drinking problem.

A special military board convened in Washington and investigated Doherty’s case for a month. He escaped a court martial, but the army brass ruled that he was “unfit for the service by reason of lack of good moral character.” Doherty complained that he never got an adequate chance of “explaining or disproving these malicious false charges,” but he was mustered out of the service on December 27, 1870.

Doherty recovered from that setback, building a successful civilian life in the years that followed. He married, raised a son, found various government jobs, and by 1886 he had landed a well-paying if unexciting sinecure as general inspector of paving in New York City’s public works department. Doherty probably would have been content to live the rest of his life in relative obscurity.

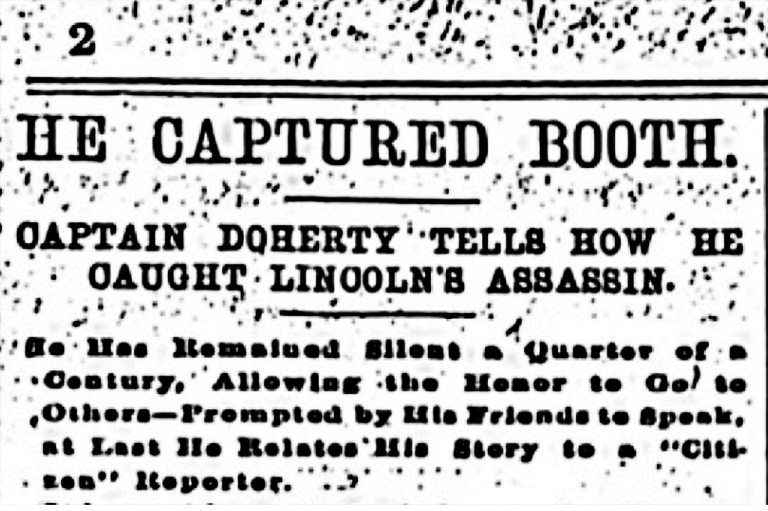

But more than two decades after the war Doherty was again thrust into the spotlight. The Brooklyn Citizen, a New York newspaper, ran a major feature on the local hero, with the headline all in capital letters: “HE CAPTURED BOOTH.” “He has remained silent,” the newspaper reported, “allowing the honor to go to others.”

Doherty got more publicity when in 1890 Century magazine published an expanded version of the detailed military report he had filed soon after Booth’s capture and death. That same year, Doherty’s legacy was secured when the definitive tenvolume biography of Lincoln written by his private secretary, John G. Nicolay, and the future secretary of state, John Hay, was published, crediting the Booth manhunt to “a party under Lieutenant E.P. Doherty.”

In 1895 the New York Times added its prestige to the scales of history with a lengthy story about the city’s paving inspector who “commanded the company of cavalry which tracked Booth to his hiding place.” Much more than he had in the battle for the reward money, Doherty, it seemed, had emerged victorious.

Doherty also reconnected with his fellow army veterans. He became a commander of a local branch of the Grand Army of the Republic, a Union Army veterans group, and served twice as grand marshal for New York’s Memorial Day celebrations.

Doherty died of heart disease at his New York home on April 3, 1897. He would have been pleased with the headline of the obituary that ran the next day in the New York Times, which was simple and to the point: “He Commanded the Men who Hunted down the Assassin of Abraham Lincoln.”

Edward P. Doherty was buried in the American military’s hallowed grounds at Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, D.C. His tombstone reads: “Commanded detachment of 16th N.Y. Cavalry which captured President Lincoln’s assassin April 26, 1865.”

The man from small-town Quebec had won his battle with history.

The Altar of Freedom

Canada and America’s Civil War

Over the course of America’s bloody four-year Civil War from 1861 to 1865, around thirty thousand to fifty thousand Canadians enlisted to fight — and they did so valiantly. At least twenty-nine earned Medals of Honour; five of them became Union generals. Many paid the ultimate price for valour: an estimated five thousand to seven thousand died.

The American Civil War pitted twenty-three Northern states, which remained in the American Union, against eleven Southern “Confederate” states, which claimed the right to secede from the Union. The schism was primarily caused by the Southern states’ desire to retain and expand the institution of slavery as American settlement moved westward, and the Northern states’ desire to limit, or even abolish, slavery.

Canadians signed up overwhelmingly on the Northern side. For those looking for adventure or in need of a small but steady salary, it was certainly geographically easier to join U.S. President Abraham Lincoln’s Union Army. Tens of thousands of citizens from what was then British North America — especially French Canadians — had already settled in the northeastern states, looking for work. As many as five to ten per cent of some regiments in Maine, Massachusetts, and Michigan were francophones.

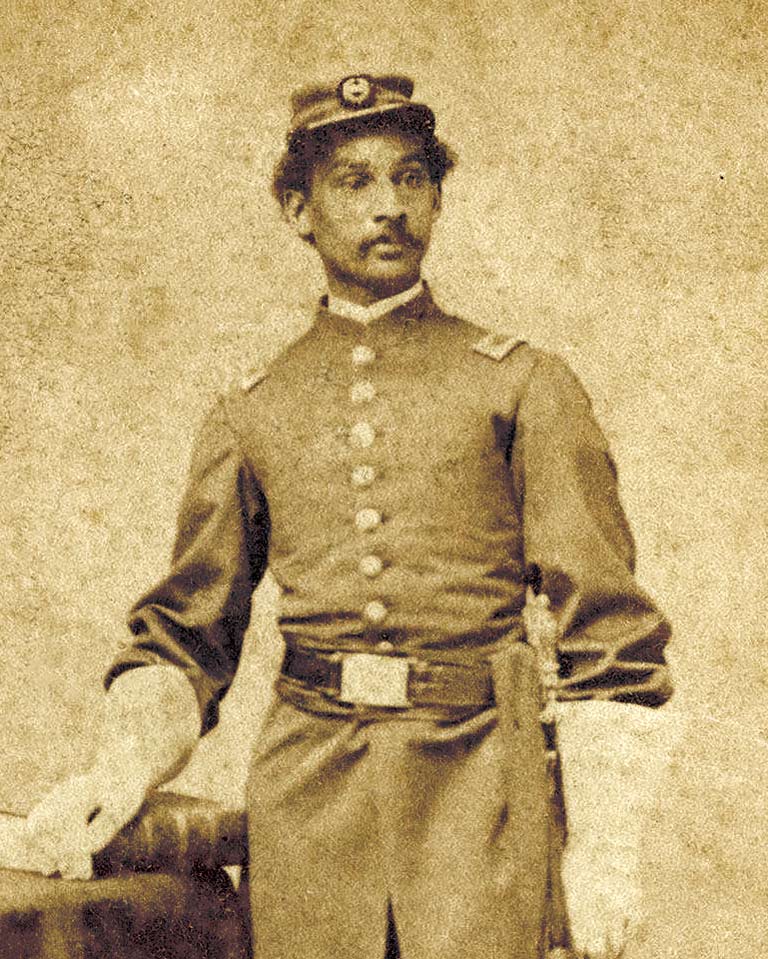

Many also joined out of conviction. An estimated 2,500 Black Canadians signed up, according to historian Richard M. Reid, who has chronicled their contributions. In a battle made famous by the Oscar-winning 1989 movie Glory, the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Colored Infantry — the first Black regiment in the North — stormed Fort Wagner in South Carolina on July 18, 1863. Half the men, including four Black Canadians, perished that day in the brave, but failed, assault.

Perhaps the most famous Black Canadian in the war was Dr. Anderson Ruffin Abbott. His father was a Toronto businessman and anti-slavery abolitionist who inspired Abbott to become the first Canadian-born Black doctor. In 1863 he became a contract surgeon in the Union Army, helping to treat Black soldiers who — faced with inferior training, equipment, and medical help — were injured and died at a much higher rate than their white comrades.

In far fewer numbers, there were Canadians who volunteered to fight for the Southern slave states. Perhaps the most notorious of them was George “Lightning” Ellsworth, a whiz at the relatively new technology of the telegraph who helped Confederate raiders confound their enemy by hacking into Union communications and spreading false information about troop movements and plans.

In 1864, a desperate Confederacy opened up a new front, seeking to undermine Lincoln’s government from where he least expected — north of the border. Soldiers and saboteurs were sent from Canada to attack Union prisons, engage in piracy on the Great Lakes, and raid border towns.

The sympathies of many members of Canada’s political and financial elite lay with the Confederacy. Like their wealthy counterparts in England, they had business ties with the cotton-producing South. They also felt more attuned to the conservative aristocracy of the South than to what they saw as Lincoln’s dangerous democratic populism.

The major newspapers they owned were decidedly pro-South. The Globe, published by fervent abolitionist George Brown, was an exception. More typical was the Niagara Review, which denounced Lincoln as a “mad, blood-stained despot at Washington.”

Montreal Police Chief Guillaume Lamothe was forced to resign when it was exposed that he collaborated with Confederate bank robbers who raided a small town in Vermont. The wealthy Toronto politician George Taylor Denison III colluded with Confederate agents and spies.

Still, the hearts of most ordinary Canadians were with the North. “Canadians should be especially proud of the part they took in that epoch-making period of the world’s history,” Abbott told a military memorial gathering decades after the war. “When thirty thousand of them left their homes and went forward to fight … thousands of our comrades poured out their blood upon the battle field as a libation upon the altar of freedom.”

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement