A River Runs Through Us

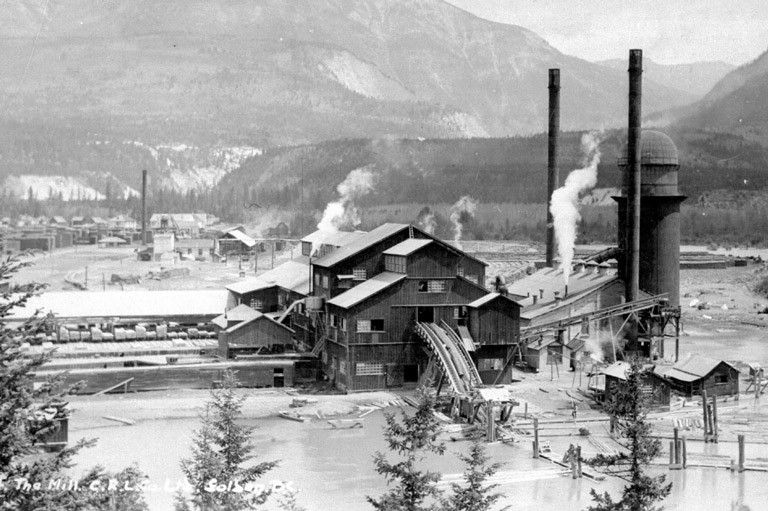

The Columbia River is the fourth-largest river in North America. Stretching from the mountains of southeastern British Columbia and flowing south across the U.S. border, its drainage area includes seven American states. In 1944, Canada and the United States agreed to talk about sharing the conservation and management of this massive river system. Twenty years later — following a devastating flood in 1948 that literally wiped Vanport, Oregon, off the map — both countries implemented the Columbia River Treaty.

“It ought to be remembered that there is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success, than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things. Because the innovator had for enemies all those who have done well under the old conditions, and lukewarm defenders in those who may do well under the new.”

Machiavelli, The Prince, 1532

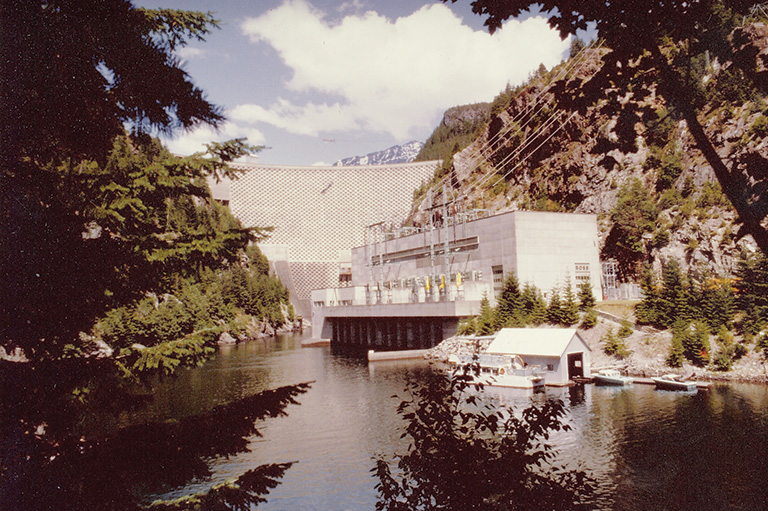

As a result of the treaty, the Columbia River is now the most dammed river in North America and the continent’s biggest hydroelectricity producer. It is also perhaps the classic example in the world of the successful and equitable sharing of downstream benefits between two countries.

The U.S. agreed to pay British Columbia an advance of $65 million — representing half of the estimated value of the reduced flood damage in the U.S. from the years 1964 to 2024. The U.S. also agreed to provide B.C. with the annual value of the marginal power generated — the so-called Canadian Entitlement. The Canadian Entitlement is currently worth between $60 million and $300 million per year; the amount varies depending on the price of electricity.

The treaty runs in perpetuity. However, 2014 and 2024 are important years. In the year 2014, Canada or the U.S. can, for the first time, give ten years notice to unilaterally terminate the treaty. And in the year 2024, unless there is an agreement to the contrary, the coordinated flood control portions of the Columbia River Treaty expire.

With 2014 fast approaching, some people on both sides of the border say the treaty is not broken, so no one should be trying to fix it. However, critics say the very simplicity that has made the treaty successful has also made it woefully out of date. For example, they say that in 1964 the enormous ecosystem impacts of the treaty on wildlife, fish, and water quality were not contemplated, the impact of climate change was largely unknown, and the Aboriginal peoples onboth sides of the border were not consulted, nor were their interests accommodated.

If either country gives notice to terminate the treaty, the situation is more complex.

In 2011 alone, over fifteen hundred residents on the Canadian side took part in a series of community meetings to discuss issues of concern, including: The removal of debris from reservoirs so that people could use these bodies of water for tourism and recreation; how to deal with invasive aquatic species; how to avoid damage to Aboriginal archeological sites; and how to ameliorate the damage from dust storms when reservoir levels are low.

Many questions have arisen. Should Canada and/or the U.S. give ten years notice in 2014 to terminate the treaty? What would termination mean as a practical matter? If there were no treaty, is Canada still obliged to prevent flooding in the U.S.? Is there any way that the existing treaty can be adjusted to include values and interests that were not prominent when the treaty was first negotiated?

If the U.S. and Canada do nothing in 2014 or beyond to terminate the treaty then it will be business as usual, with one important exception: The current coordinated operation for flood control in the U.S. would terminate in 2024, unless there is an agreement to the contrary. As a practical matter, this would mean that flood control, particularly in the U.S., would likely be much more challenging and expensive.

The fact that the Columbia River Treaty appears to have worked reasonably well for the past forty years, or that international treaties are increasingly difficult to negotiate or adjust in the present political climate on both sides of the border, should not deter those who wish to see constructive change.

The pros and cons of an adjusted treaty should be evaluated in both countries. Such an evaluation should go beyond the status quo to include a critical review of how best to conserve and protect the environment, as well as to respect the interests of those living near the Columbia River. Lessons can also be learned from governance of the other 246 international drainage basins around the world.

Last, but not least, all who will be involved in determining the future of the Columbia River in 2014 and beyond should seek to overcome what Machiavelli identified as the “incredulity of men who do not readily believe in new things until they have had a long experience of them.”

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Sponsored by

This article, prepared for Canada’s History, is part of a four-part series on environmental history generously sponsored by the Walter & Duncan Gordon Foundation.

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk necktie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. Made exclusively for Canada's History.