Museum Draws Attention to the Indian Act

A new museum exhibit identifies issues with the federal Indian Act and challenges people to think about its historical and continuing impacts on First Nations across Canada.

“The whole act should be surprising to people today in that it’s based on the idea that the government should make all decisions with respect to First Nations people on the land that belonged to them,” said Karine Duhamel, curator for Indigenous rights at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR) in Winnipeg.

The Canadian government first introduced the act in 1876. It has since been revised several times and continues to affect the lives of First Nations people in many ways, including regarding land use and eligibility for Indian status.

Other consequences of the Indian Act have included children being taken from their families and put in schools with the goal of assimilating them into mainstream society; women facing the loss of their identities and rights for marrying people outside their communities; and prohibitions against practising Indigenous cultures.

Duhamel, who identifies as Métis and Anishinaabe, said the act is responsible for many issues in First Nations communities. For example, it requires band councils to hold elections every two years, something Duhamel argues doesn’t allow for long-term changes in the community.

Even the name of the act is a problem, she said, since “Indian” is an outdated term.

The goal of the CMHR exhibit is to inspire conversation, Duhamel said. She wants people to understand that First Nations communities can’t just “move on” from the past and that the problems are still ongoing today.

“I hope that people understand that colonialism isn’t totally dead.”

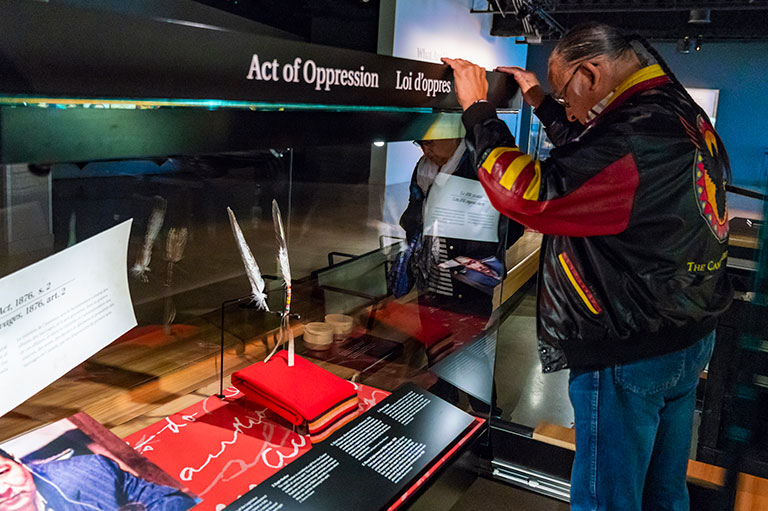

The CMHR worked with First Nations elders and advisors to put together the exhibit, which features a number of traditional Indigenous items that symbolize aspects of the Indian Act.

A cradleboard represents the continued celebration of Indigenous traditions despite that the act outlines ways to assimilate First Nations people into society. A wampum belt inspired by the Dish with One Spoon Treaty, which focused on sharing land, contrasts how governments removed First Nations people from land that was offered to settlers.

The exhibit also displays eagle feathers, including one held by former Manitoba politician Elijah Harper, whose refusal to support the Meech Lake Accord led to the collapse of the constitutional agreement. The feathers symbolize the Indian Act’s failure to acknowledge First Nations’ traditional government systems.

Duhamel said displaying these items shows the strength of Indigenous people and how their cultures have survived even under the Indian Act.

The exhibit at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg continues until summer 2019. There are plans to create a larger related exhibition in the future.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Nominate an exceptional history project in your community for this year’s Governor General's History Award.