Experiencing Human Experience

From a distance, the Canadian Museum for Human Rights looks grand. From many vantage points in the city, the Winnipeg skyline is pierced by the tower that juts out of the building’s flowing panes of curved glass the seem to hug each other effortlessly.

And the closer you get to the building, the smaller you feel.

The museum is designed by New Mexico architect Antoine Predock to mimic “a journey from darkness to light” both architecturally and metaphorically. The first levels are a series of dimly lit galleries that feature the raw stories of people around the world who have had their human rights taken away. As you climb further up the glowing white alabaster ramps, light begins to stream through from the outside and the galleries mirror this natural optimism with exhibits on expression and inspiring change.

Standing on the first of the museum’s eight levels, the task ahead of you can feel daunting. And it is. Walking into the first gallery room, I was greeted by a wall of colourful panels and a question: What Are Human Rights? As a video on the opposing wall featured people defining human rights in different terms and languages, I slowly meandered down the line of stacked panels. In chronological order, the panels offer one hundred key events, ideas and measures that tell the global story of human rights.

For me, the timeline felt like a global unification in many ways. It revealed that different religions and governments throughout time have actually held very similar values. I smiled as my eyes passed almost simultaneously over the dates AD 4–30 and AD 570–632. The former period, representing when Jesus of Nazareth taught the virtues of love and compassion, and the latter period, signifying when the Islamic prophet Muhammad preached tolerance, charity and equality.

Further down the line, my smile faded as my gaze stopped on a panel that read: 1915–1923 Ottoman government commits genocide against Armenians. I began to realize this timeline was effectively depicting how the ideas of basic human rights have been around since 4000 BCE and even earlier, yet thousands of years later, humanity is still struggling to maintain decency and equality for all.

Just past the timeline there is a large circular theatre made of curved wooden slats. This marks the beginning of the Indigenous Perspectives gallery that features art and ideas from Indigenous culture.

In this gallery I found myself drawn to an evocative hanging art instillation that resembles an elemental waterfall, constructed with hundreds of cascading clay beads. The piece, by Rebecca Belmore, is called Trace, clay and steel, and was created in honour of the Indigenous peoples who originally inhabited the land upon which the museum now stands. The clay used in the piece was extracted from the ground beneath the city, and moulded by the hands of children and adults who collaborated with the artist.

The next gallery is the largest of the museum and has been named Canada’s Journey. If you felt so inclined, you could spend your entire day roaming in and out of the many kiosks that depict the ways in which Canada has faltered on its journey to achieve human rights.

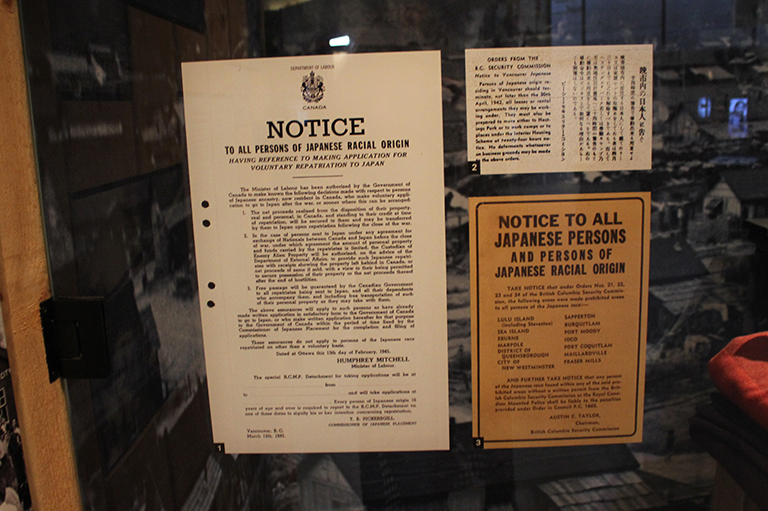

The first kiosk I stopped at featured the experience of Japanese-Canadians during the Second World War. My heart sank as I read of how Canadian-born citizens were taken from their homes and forced to live in internment camps for the rest of the war.

In a kiosk about voting rights, I learned that many minority Canadians — including those of Chinese, Japanese and African descent — did not have the right to vote in Canada in 1917.

At one of the kiosks, I used an interactive globe to watch Canadian immigration stories from hundreds of different countries. One of the videos told the story of a man who worked as a doctor in the United States during the Vietnam War. To avoid the draft, he and his wife flew into Quebec just after midnight, as this was when the French-Canadian immigration officers would be on duty. These officers were known to be more sympathetic to draft dodgers because of their own experience in the First and Second world wars.

Moving from kiosk to kiosk, I learned about Canadian stories that had never before crossed my mind, exploring topics like language rights, freedom of consciousness rights, and worker’s rights.

At this point I was experiencing information overload. I found the content a bit emotionally overwhelming. Thankfully, the next level of the museum offered some much-needed serenity. Along with some interactive games, level three features the Garden of Contemplation. This elemental oasis of rocks, plants and water was a great space for me to reflect on the things I had just experienced. Predock understood the physical and mental toll the museum could have on visitors, and so he designed the building with seating areas on each floor for people to sit and reset.

However, I did not stop long before making my way up to level four. At this point I was halfway through my journey to the top and completely unprepared for what I was about to experience.

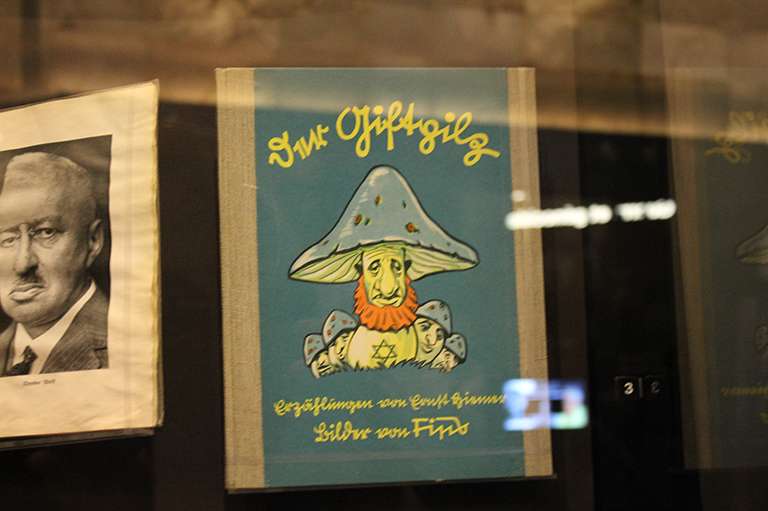

Examining the Holocaust was the next gallery, and it was difficult. Huge floor to ceiling panels told the story of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi government. For me, the most powerfully aspect of the exhibit was the curated artifacts and photos that graphically illustrated how truly horrifying and inhuman the Nazi regime was.

Among the items are children’s books written and designed to portray Jewish people as evil.

There are crossed-shaped medals with swastikas in the center that were given to German woman who bore “pure” German children. Pictures of preschool students being taught how to hold their arms to “Heil Hitler” and a wooden bust of a Jewish man that was used for teaching the blind how to identify Jewish people.

The next gallery — exploring the history of several genocides, including those that occurred in Rwanda and Bosnia, and the mass killings of Armenians by the Ottoman Empire — was equally disturbing.

In a small theatre, I sat down to watch a short film on the man-made famine suffered by the citizens of Ukraine. The genocide known as the Holodomor was caused by the Soviet government in 1932 by cutting off the nation’s food supply. The death toll of the Holodomor is unknown, as the genocide was hidden from the rest of the world for more than fifty years — but it’s believed that millions of Ukrainians died.

As I walked through the next three levels of the museum I felt numb. The interactive games felt insignificant. Though the galleries were brighter, and focused on awareness and change, I could not shake the stories I had experienced. After reading about massacre after massacre, I was left with feelings of helplessness — and also guilt. Guilt because here I am — privileged — walking through a beautiful piece of architecture, learning about human tragedy I’ve never experienced and war crimes I’ll probably never be subjected to. I’m looking into these people’s experiences at arms length, through shiny glass and computer screens. How is this fair? I asked myself.

On level seven, the museum offered me a space to answer the question posed at the beginning of my journey: What are human rights?

Little blank cards and markers of different colours awaited me at a circular table. I was invited to give my input, but I felt frozen.

What could I possibly have to say that would somehow change the faults of the human condition?

I took the elevator up to level eight: Israel Asper Tower of Hope. From here I saw the city from above, the water, the streets and the people. In a way, everything felt peaceful. Standing so high above it all, I felt a sense of hope restored. And it was then that I realized that the tower had done its job.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement