NATO 75

Seventy-five years ago, on April 4, 1949, Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, and nine other European states signed the treaty that created the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). From 1949 to today, the alliance has survived the Cold War for which it was created and has more than doubled in size to thirty-one members. And it is still growing: Finland joined the alliance in 2023, and NATO is expected to add one more member when the ratification of Sweden’s membership is complete.

NATO, whose member states represent nearly one billion people, is the largest and most powerful military alliance in history. But the fact that it has existed for so long and has grown so large would have surprised the men who signed the North Atlantic Treaty in 1949. They had created NATO as part of a Cold War strategy to bind the United States to Western Europe. The alliance’s purpose was to prevent the Soviet Union from expanding its influence and control in Europe. And yet NATO has lasted long past the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union. Today, in an echo of that earlier history, NATO’s primary purpose is to deter Russia from aggressive moves against NATO members.

Historically, most military alliances have been formed in wartime. They are tools of necessity and circumstance, used by leaders to wage a specific conflict. NATO is different. It was created to prevent a recurrence of war in Europe.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Europe lay in ruins. Cities and towns were destroyed. People were starving. Leaders in London, Ottawa, and Washington worried that the awful conditions in Europe might allow the Soviet Union and local Communist parties affiliated with Moscow to take control of central and Western European states by promising Europeans a radical, if superficially attractive, way of organizing their war-torn societies. Canadian, American, and British leaders worried that Communist political victories in Europe would draw European states into the Soviet orbit, ultimately allowing Moscow to control the whole continent. The Second World War had just been fought, and won, to prevent Europe from falling under the command of a single totalitarian state; to leaders of the day, the expansion of Soviet Communism represented another effort by a totalitarian state to dominate Europe. As U.S. President Harry S. Truman put it: “There isn’t any difference in totalitarian states. … Nazis, Communist or Fascist … they are all alike. … The police state is a police state, I don’t care what you call it.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

For the first few years after the war, the United States sought to stave off the attractions of Communism by providing more than $13 billion in financial aid to rebuild Europe. U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall, for whom the Marshall Plan was named, said the program was designed to restore “the confidence of the European people in the economic future of their own countries and of Europe as a whole.” But in the late 1940s it appeared as though even this substantial economic support was not enough to prevent the Soviet Union from gaining influence in European capitals.

Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union and Secretary-General of its Communist Party, repeatedly flexed his military muscle to extract concessions from European states. The world had watched when, after the end of the war, the U.S.S.R. made steep demands against Finland. Finnish leaders ceded part of the industrially important province of Karelia and other territory to the Soviet Union, which resulted in the forced movement of hundreds of thousands of Finns. In addition, a 1948 treaty put Soviet conditions on Finland’s foreign policy. Finland granted these demands knowing that its war-weary people could not resist the Soviet Red Army.

Also in 1948, Norway’s leaders learned the Soviet Union was preparing to make demands of their country. Norwegian diplomats contacted their American, British, and Canadian counterparts, warning that the people of Norway, who had also suffered during the war, would be unable to stand alone against Soviet threats. As U.K. Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin put it: “The Russians seem to be fairly confident of getting the fruits of war without going to war.”

The Soviet Union had suffered enormous casualties in the war, too. But it had built up a fearsome military machine of more than eleven million troops that had pushed the Nazis all the way back to Berlin. Even if the postwar Red Army was not as strong as American intelligence assessments assumed, Stalin’s willingness to threaten conflict against people recovering from a brutal war gave him an advantage. The only solution was to find a new system whereby states would not have to stand alone in the face of Moscow’s threats.

American, British, and Canadian diplomats met in Washington in March 1948 to begin a series of conversations on a new system for security in Europe. Negotiations were already occurring among European states, including the United Kingdom, to create a defensive alliance in Western Europe; soon, the negotiations merged to include both groups. NATO’s founding member states — Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Denmark, France, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, and Portugal — are not all located along the North Atlantic. The name North Atlantic Treaty Organization was chosen to make it clear that other friendly nations, like Australia, had been excluded only for geographic reasons. NATO was all about Europe, backed by North America.

Negotiations to create NATO were not easy. The United States had a strong political tradition of refusing to join alliances, and there was serious debate within the country as to whether an open-ended commitment to Europe was necessary. George Kennan, an American diplomat famous for his assessments of the Soviet Union, reassured his European colleagues it was “unthinkable that America would stand idly by” if the Soviet Union made “an aggressive move against any country of Europe.” The point of the alliance, others argued, was to create a unified front that would prevent the Soviet Union from taking aggressive action in the first place.

Advertisement

Although American political leaders were ultimately convinced of the need for an alliance, they insisted that the treaty’s language must not commit the United States to war, since that remained the prerogative of the U.S. Congress. As a result, the treaty’s Article 5 states that the signatories agree “an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all” — but what to do in case of such an attack remains up to each ally. This arrangement disappointed the other signatories, who wanted a stronger assurance that the Americans would fight to defend their allies.

On April 4, 1949, the treaty was signed in Washington by representatives of the twelve founding nations. Henceforth the states of Europe would not be susceptible to Soviet “salami tactics” — that is, being sliced off one-by-one by pressure and threats from Moscow. In the case of any such threats, Stalin would know that he was facing a bloc of states. Indeed, the purpose of the treaty was so explicit that the Dutch ambassador suggested it should begin with the salutation, “Dear Joe.”

At the beginning, the treaty was flimsy and untested. It was a diplomatic agreement with no significant military element. There were no NATO forces or command structure. In only a few years, however, NATO would develop into the military alliance familiar to us today.

In June 1950, North Korean forces crossed the thirty-eighth parallel into South Korea and started the Korean War. Korea is a long way from Europe, but American and European leaders worried (incorrectly, as it turned out) that the war marked the start of a Soviet global offensive. Only after the end of the Cold War did archival records reveal that the Soviet Union had consented only to a limited war on the Korean Peninsula. The NATO allies had no such reassurance at the time, and they believed it was essential for NATO to establish an integrated military command to defend its member states.

In 1951 American General Dwight D. Eisenhower — who had led the liberation of Europe in the Second World War as supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force — was appointed NATO’s supreme allied commander, Europe. His organization, with its international military staff, had many deliberate overtones of the combined command that had defeated Nazi Germany. Europe, however, had few men under arms due to the casualties of war and the need for rebuilding. To make up for this, the United States and Canada each sent thousands of troops across the Atlantic: In the 1950s there were more than ten thousand Canadian troops and more than four hundred thousand U.S. forces in Europe. Canadian and American forces ended up remaining in Europe for the entire Cold War, until the dissolution of the U.S.S.R. in the early 1990s — and there are American and Canadian troops in NATO Europe again today.

The deployment of North American troops addressed the short-term problem of strengthening Europe’s defences. To improve NATO’s strategic position and war plans, the alliance added Turkey and Greece as members in 1952. In 1955, the Federal Republic of Germany — known colloquially as West Germany -— joined the alliance, bringing in Germany’s industrial and potential military strength. In response to this, the Soviet Union formally established the Warsaw Pact, an alliance of the U.S.S.R. and several Eastern European states controlled by Communist governments loyal to Moscow. These two competing alliances froze international relations in Europe for decades.

For most of the Cold War, the Canadian troops deployed in Europe included a brigade of ground forces and an air division. For roughly a decade, from the early 1960s to the early 1970s, the Canadians were equipped with nuclear-capable weapons. This was part of a complicated agreement in NATO whereby non-nuclear countries like Canada fielded artillery weapons and strike-fighter aircraft that were capable of firing nuclear weapons. The nuclear warheads technically remained the property of the United States and were kept under American guard at a NATO base in Germany. But if the Cold War had turned hot, the Canadian ground and air forces would have waged nuclear war.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Canadian leaders always viewed NATO as an organization with a positive purpose, rather than one designed only to deter war. Lester Pearson, Canada’s secretary of state for external affairs and future prime minister, told his cabinet colleagues that the allies were a “real commonwealth of nations” that could build on shared democratic traditions to deepen their “political and economic unification.” During the treaty negotiations, Canadian diplomats pushed for a clause that contained these ideas. The result was Article 2, often called the Canadian clause, which reads: “The Parties will contribute toward the further development of peaceful and friendly international relations by strengthening their free institutions, by bringing about a better understanding of the principles upon which these institutions are founded, and by promoting conditions of stability and well-being. They will seek to eliminate conflict in their international economic policies and will encourage economic collaboration between any or all of them.”

While NATO survived the Cold War, it faced many crises over the decades. In the 1950s and early 1960s, several European member states called on the alliance to support wars to maintain their empires. The United States and Canada disagreed with this, insisting that NATO was not an imperial organization. This led to bad feelings when most allies refused to aid the French and Belgians in retaining their imperial control of Algeria and Congo (now Democratic Republic of the Congo), respectively.

In the 1960s, after the Cuban Missile Crisis — a high-stakes standoff in which the Soviet Union stationed nuclear missiles in Cuba and the United States forced the missiles’ removal — tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union subsided. In this era of détente, many citizens in NATO countries began to doubt whether the alliance was still necessary. French President Charles de Gaulle pulled French forces from NATO’s integrated military command, although France did not actually leave the alliance. Critiques of NATO became even more pointed in the 1970s and 1980s, with major demonstrations against NATO’s nuclear weapons. Canadian leaders and their allied colleagues thought carefully about other options for international security, but they always concluded that the world was safer with NATO than with any alternative.

In November 1989 the Berlin Wall came down, beginning an unexpected and speedy end to the Cold War. The Warsaw Pact disintegrated, and in 1991 the Soviet Union collapsed into its separate republics, of which Russia was the largest. The end of the Cold War raised serious questions about NATO’s future. The dissolution of the Soviet military threat allowed the NATO allies to spend less on defence, and by 1992 the last of the Canadian troops garrisoned in Germany were brought home. But the allies ultimately agreed to keep both the treaty and the organization active.

In the 1990s, NATO members made two important decisions. One was to intervene in the wars that followed the dissolution of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia into independent republics. As armed forces in these wars committed atrocities against civilians, the United Nations launched a series of peacekeeping operations to protect civilians and to end the fighting. Closely connected to the United Nations operations in Bosnia and Herzegovina, NATO conducted air strikes against the Bosnian Serb Army when it attacked UN-designated safe areas in 1995.

The Dayton Accords ended the fighting in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1995, but conflict continued in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, which was composed of the two former Soviet Yugoslav republics of Serbia and Montenegro. In 1998, NATO helped to broker a ceasefire between the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Kosovo Liberation Army, which sought independence for the Kosovo region of Serbia. However, fighting resumed in 1999, marked by massacres and other atrocities.

When the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia refused to yield to international pressure to end the conflict and to introduce a NATO peacekeeping force, NATO waged a lengthy bombing campaign against it, forcing it to withdraw its forces from Kosovo, where they had been committing ethnic cleansing. The 1999 intervention was not sanctioned by the United Nations, and the bombing raised tensions between NATO and Russia, a traditional ally of Serbia. These events marked NATO’s transformation into an alliance willing to exercise its military force for purposes beyond self-defence and beyond the boundaries of NATO member states.

In the same decade, the NATO allies decided, for a number of reasons, to expand the alliance by admitting former members of the Warsaw Pact. These states had asked to join NATO, seeing the alliance as a source of security and opportunity for their new democracies. The United States, for its part, wished to keep NATO in existence to deter a possibly resurgent Russia. Perhaps most importantly, NATO had provided a home for West Germany’s rehabilitation after the Second World War; many leaders believed NATO’s most critical role in the post-Cold War world would be to bind Germany to the other Western powers. In fact, NATO’s first post-Cold War expansion occurred in 1990, when East Germany — a former member of the Warsaw Pact — unified with West Germany. This moved the alliance’s boundary eastward. In 1999 Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary joined NATO; several new rounds of memberships followed in the early 2000s.

Advertisement

In 2014, Russian forces annexed Ukraine’s Crimea region. Russian military units also entered Ukraine’s eastern regions and fought alongside Ukrainian separatists against the country’s armed forces. Those aggressive actions led NATO allies to improve the alliance’s military posture and readiness. In 2016, NATO established a number of multinational battle groups in northern, central, and eastern Europe. Since 2016, Canada has provided approximately one thousand troops to lead NATO’s battle group in Latvia; in 2023, the Canadian government announced plans to add a tank squadron of fifteen battle tanks.

Russia’s aggression in Crimea helped to convince a new generation of NATO leaders that the alliance retained its purpose of deterring war and defending Europe — even if the aggressor was Russia and not the Soviet Union, which had been, comparatively, a much stronger strategic challenger. This conviction was especially important when Donald Trump was elected U.S. president in 2016. Trump was the first and only American president to openly question the future of the alliance, and the New York Times has reported that he considered withdrawing the U.S. from NATO. The alliance’s role in countering the Islamic State — a transnational group responsible for atrocities in Iraq and terror attacks in Europe — as well as the jolt given by Russia’s invasion of Crimea allowed the other allies to fend off Trump’s suggestions that the alliance was outdated and unnecessary.

The large-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has been the most important event in NATO’s history since the end of the Cold War. Although NATO has not invoked Article 5 and is not a belligerent in the conflict, NATO member states have provided training, weapons, and support to Ukraine. As Canadian Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland explained in a speech in October 2022, “The immediate and necessary reaction to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has been to deepen and expand our core military alliance — NATO.”

Since 2022 NATO has increased its forces in allied countries facing Russia. The battle groups have grown in size, and allies have sent ships and air forces to the region. Like the commitment of Canadian and American forces to Western Europe in the 1950s, the troops now in Eastern Europe give substance to the idea of unity and collective defence. They also serve to deter the Russians from expanding the war. NATO’s strong defensive posture has provided a corridor that allows Ukraine’s supporters, which include NATO allies but also states from elsewhere in the world, to supply Ukraine with weapons, ammunition, and other aid.

In the 1940s, the diplomats who created NATO were thinking about the immediate problem of the Cold War and were not planning on building an alliance that would last decades. And yet, the principles that guided their thinking in 1949 remain relevant today. In the aftermath of the Second World War, leaders were convinced that the maintenance of military power — giving allies the ability to defend themselves and to deter a potential aggressor — was the best way to prevent a third world war. In the words of the ancient Roman adage, Si vis pacem, para bellum: If you want peace, prepare for war.

NATO and Canada in Afghanistan

For almost two decades, from 2003 to 2021, NATO led an extensive effort to secure and rebuild Afghanistan. A significant change from the alliance’s activities during the Cold War, NATO’s commitment to Afghanistan gave the allies a common cause during a period when the purpose of the alliance was in question. Yet it was a dangerous and deadly undertaking. More than 40,000 Canadian soldiers served, thousands were injured, and 158 were killed — along with one Canadian diplomat and one Canadian journalist — in a mission that ultimately ended in frustration.

NATO’s attention was drawn to Afghanistan by the terror attacks on New York and Washington on September 11, 2001. The next day, after a suggestion by Canada’s permanent representative to NATO, Ambassador David Wright, the allies invoked Article 5 of NATO’s founding treaty for the first time in history, signalling that they considered the attack on the United States an attack against them all.

Weeks later, invoking its right to self-defence under the United Nations Charter, the United States took military action against Afghanistan, where terrorist leader Osama bin Laden sheltered under the protection of the Taliban government. Canada participated in these initial military operations as part of an ad hoc coalition; this was not a NATO mission.

When the Taliban government fell in late 2001, the United Nations established an International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) to maintain security in Kabul, the Afghan capital. In August 2003, NATO formally assumed leadership of ISAF. “This new mission,” stated NATO’s Deputy Secretary-General Alessandro Minuto Rizzo, “is a reflection of NATO’s ongoing transformation, and resolve, to meet the security challenges of the twenty-first century.”

Canada sent an infantry battle group and a headquarters team to Kabul to lead a multinational brigade. In its early years, NATO’s ISAF role was often called a “peacekeeping operation” in news reports, but the phrase is misleading. The mission quickly expanded to include a counter-insurgency against the Taliban, which had regrouped and shifted to guerrilla tactics.

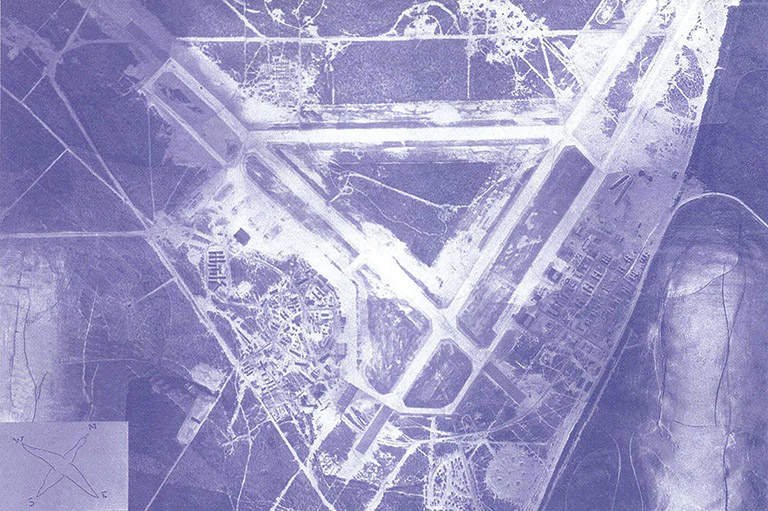

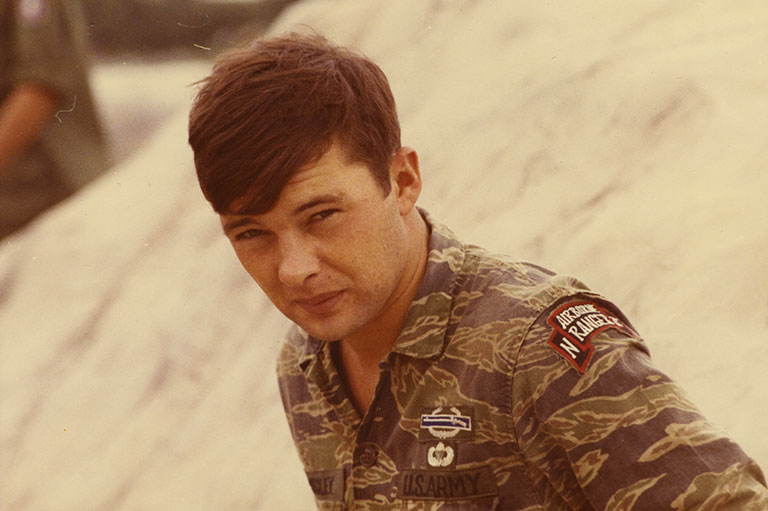

ISAF expanded its operations beyond Kabul and placed NATO forces throughout the country to establish security and to support the new Afghan government. Canada led a Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) in Kandahar province beginning in 2005, which brought together soldiers and civilians — diplomats, development specialists, police officers, and others — to help build dams and schools and to combat disease. To protect the PRT’s efforts, Canada also sent military units — at times amounting to nearly three thousand troops — to Kandahar. In 2006, the Canadian Forces led an offensive against the Taliban named Operation Medusa, which Sten Rynning, a scholar of NATO, has called “ISAF’s first real battle.” The fierce fight marked the beginning of years of counter-insurgency warfare.

In 2011, Canada ended its combat mission and shifted to training Afghan security forces. In 2014, ISAF handed responsibility for security to the Afghan National Security Forces; the ISAF mission ended, and Canadian troops returned home. NATO began a new non-combat mission called Operation Resolute Support to continue training and assisting Afghans. But the Taliban gained strength and threatened the Afghan government. In August 2021, following the withdrawal of American forces, the Taliban seized Kabul. The Afghan government disintegrated, and NATO terminated Operation Resolute Support. Twenty years after the September 11 terrorist attacks, the Taliban had taken back control of the country. — Timothy Andrews Sayle

In today’s environment of misinformation and disinformation, it can be hard to know who to believe. At Canada’s History, we tell the true stories of Canada’s diverse past, sharing voices that may have been excluded previously. We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past, highlighting our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages – award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts. Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!