Children of Conflict

Four years, the length of the First World War, is a long time in the life of a child. For youngsters across Canada, the war years meant many things: the absence of fathers and brothers, a chance to make important contributions to the Allied war effort, opportunities to learn and to worry about events at the front, and, beginning in late 1918, a deadly influenza pandemic.

Old enough to remember the war but too young to fight, this generation of Canadians would come of age in the shadow of the “lost generation,” the cohort of men who fought and died in the First World War. Although Canadian children spent the war years far from the front lines, they were not mere bystanders to history — they were also active participants in a global conflict that forever altered their lives.

The enlistment of a father or older brother was one of the most fundamental ways the Great War changed children’s lives. Approximately twenty per cent of the 470,224 Canadian men who served overseas were married, and a large number of these men were also fathers. An even larger number of children watched their brothers, uncles, cousins, and neighbours enlist or be conscripted as the war dragged on.

Evidence of the familial and patriotic pride felt by these young people can be found in the letters they wrote to the children’s pages of Canadian magazines and newspapers. Many of these missives began by describing the writers’ enlisted relatives and their thoughts about the war, before moving on to discuss other aspects of their daily lives, such as pets and favourite books.

During the fall of 1916, for example, Estella Grant, a fifteen-year-old from Kilburn, New Brunswick, wrote in a letter to the Family Herald and Weekly Star, “I have two cousins at the front, besides an only brother in the 188th Battalion at Camp Hughes. He went West last August and enlisted in February at North Battleford, so you see I have never seen him in khaki. But we have several good pictures of him. I hope he will be able to get home for a visit before he goes overseas. I hope the war stops before my brother gets into the trenches. If I were a boy I would try to be accountable for a few Germans.”

The extended absence of fathers and older brothers meant that many children across Canada supported their families with paid or unpaid labour while their relatives were overseas. After Sidney Brook, a farmer from Craigmyle, Alberta, joined the 113th Battalion in 1916, his sons Gordon, eight, and Arnott, six, helped their mother Isabelle care for their three younger siblings. Throughout his two-year absence — Sidney Brook survived the war and came home in 1918 — the Brook children also dug a cellar, delivered mail, and fetched milk and water.

Perhaps even more importantly, they provided emotional support to their father while he was at the front. The boys wrote letters telling him about their Christmas gifts, their baby sister, and the teeth they had lost. They also packed parcels to send to him and drew him pictures.

Sidney described how much he appreciated these thoughtful acts, writing to his wife that he kept the boys’ letters in his left breast pocket beside his Bible and that “a little dewdrop” blurred his vision while he opened gifts from his children.

Scholars have recently emphasized the importance of letters for the morale and mental health of soldiers in the trenches. As the historian Martin Lyons put it, letters from home, filled with messages of past happiness and future hope, were “a humanizing influence in a sea of brutality.”

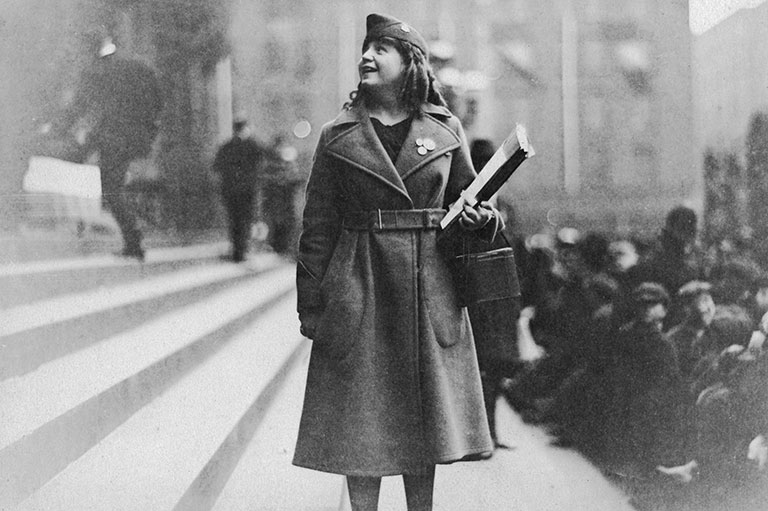

In addition to writing to absent relatives and helping their mothers with domestic chores and farm work, by 1918 Canadian youngsters had also made significant material and economic contributions to the broader Allied war effort. Children were a vital and enthusiastic unpaid labour force throughout the war.

At school and in their spare time, they produced a wide range of goods for enlisted men, including socks, scarves, bandages, and scrapbooks full of local newspaper clippings. These scrapbooks were vital sources of news from home and played a central part in many communities’ efforts to inspire soldiers to continue to fight.

Children’s unpaid war work also included collecting and scavenging bottles and cans, bones (for glue), household fat (for dynamite), sphagnum moss (an extra-absorbent substance used in medical dressings), and milkweed pods (used to make life preservers). In addition, youngsters grew and harvested fruits and vegetables, and hundreds of teenage “Soldiers of the Soil” provided valuable manpower on farms.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The nation’s young people also raised and donated substantial amounts of money to war-related charities. In 1918, for example, Saskatchewan members of the Junior Red Cross raised $15,195.33 for Red Cross war work — an amount equivalent to nearly $350,000 today.

At school and at home, Canadian youngsters were also avid consumers of war-related news and propaganda; the difference between the two was not always readily apparent. In classrooms across the country, teachers were encouraged to use the war to teach their students moral lessons about patriotism, heroism, and hard work. At school, students read about soldiers who won medals for bravery and listened to dramatic tales about such heroes and heroines as the martyred British nurse Edith Cavell.

Thousands of schoolchildren across the country also learned about Allied victories and read Sir Edward Parrott’s fifty-six-volume The Children’s Story of the War. Each volume in this massive series, like other children’s books published during wartime, celebrated youthful heroism while promoting anti-German sentiment.

One chapter, for example, tells the story of a French Boy Scout who, after having been captured by German troops, refused to disclose the location of French troops. Parrott writes that the Germans told the boy “they were going to shoot him, but he showed no fear. He walked with firm steps to a telegraph post, stood against it, and with the green vineyard behind him, smiled as they shot him dead.” This gruesome — and likely fabricated — tale, was accompanied by a moral for young readers: that it was brave and patriotic “to prefer death to the betrayal of one’s countrymen.”

It is important to note that children were not sponges who internalized this wartime propaganda uncritically. The letters children wrote to local and national newspapers suggest that they had a complex understanding of the war.

There are few echoes of the propagandistic patriotism of The Children’s Story of the War, for instance, in the letter from ten-year-old Cecil Poole of Zealandia, Saskatchewan, published in the July 5, 1916, issue of Grain Growers’ Guide: “I think war is one of the most cruel and worst things that could happen. To think of the poor orphans and also the poor fathers and mothers who mourn after their sons. It’s heart-rending to think of men shot down like beasts. I have one brother twelve years old and have just one cousin at the front, but if my brother and I were old enough we would try to take up arms for our country.”

Young Florence McGibney, writing from the southeastern Saskatchewan town of Welwyn, expressed a similar understanding of the war’s effects in a letter published in the same issue. “The men are down in trenches and are ready at any minute for an attack of the enemy,” she wrote, “and every man is careful to keep his head down, if he doesn’t want to make a target for the other side. This often happens, and then the sad news reaches home, breaking either a mother’s or a wife’s heart.”

The waiting and worrying that characterized so many Canadian children’s experiences of the war years officially came to an end with the signing of the armistice on November 11, 1918.

While adults and children took to the streets to celebrate the end of the war, Canadian victory parades were haunted by another threatening spectre: the deadly pandemic of Spanish influenza that swept across home fronts and battlefields during the final months of the war.

Schools were closed, often for several months, and newspaper headlines highlighted the tragic consequences that the flu could have for young people. British Columbia’s Agassiz Record, for example, informed its community of readers that young Mildred Evelyn Wetherell, who had succumbed to the illness on November 3, 1918, “was aged 10 years, 7 months and 25 days.”

Later that month, the Manitoba Free Press described an especially distressing case in which a nurse who entered a home encountered “[a] father and three children seriously ill and the mother dead on the sofa.” Historian Esyllt Jones estimates that approximately five hundred flu victims in Winnipeg left behind one or more dependent children, creating thousands of orphans and “half-orphans” over the span of several months.

Most orphans were sent to live with other relatives or family friends, while some were sent to local children’s homes. Children with only one living caregiver often faced great financial difficulties in an era when social services were minimal and it was considered degrading to accept public aid.

By 1919, the year when the pandemic ended and many Canadian soldiers returned home, life looked very different for Canadian children. For many young people, war work and worrying about absent relatives were replaced by grief, difficult readjustments to the presence of fathers and brothers — many of whom bore physical and psychological scars — and the material hardships that often accompanied the permanent loss of a male breadwinner’s wage.

The First World War was won with the help of Canadian children, and it was also fought for them. Sidney Brook, like many other men in uniform, hoped that this conflict would be the war to end all wars, writing to his wife, Isabelle, that he hoped their boys would “grow up to be strong manly men and never have to shoulder a rifle.”

The desire that the children of the Great War would spend their adult lives in peace was dashed by the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939. Four of the Brooks’ sons — like many other young men and women who had worked and waited as children between 1914 and 1918 — served their country in the Second World War: Gordon and Lorne with the Canadian Postal Corps, Glen with the Calgary Highlanders, and Roy as a member of the Royal Canadian Air Force. All of them survived.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

1914-1918: The War Ends

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

The war that changed Canada forever is reflected here in words and pictures.