No Man’s Land

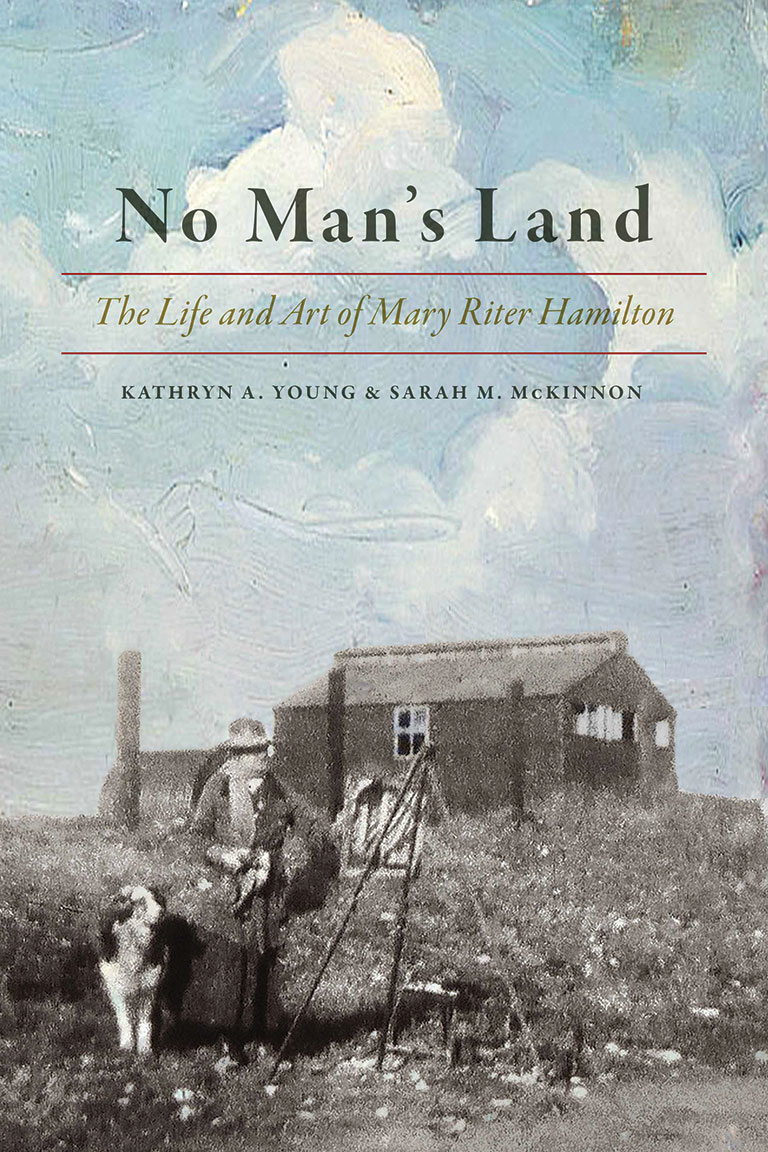

No Man’s Land: The Life and Art of Mary Riter Hamilton

by Kathryn A. Young and Sarah M. McKinnon

University of Manitoba Press, 304 pages, $27.95

Even before the armistice that ended the First World War was signed, thousands of visitors made their way to the battlefields of Europe. Many made the journey in tribute to lives lost in the conflict — a pilgrimage to the places where their loved ones spent their final days. Others felt a sense of urgency to tour the front lines and to document the impact and destruction of war.

In No Man’s Land: The Life and Art of Mary Riter Hamilton, Kathryn A. Young and Sarah M. McKinnon provide a rich biography of one woman who was compelled to paint the battlefields in the immediate aftermath of the First World War.

Born in 1868 in Bruce County, Ontario, Hamilton was a Canadian artist who by the age of twenty-two had suffered her own personal tragedies with the death of her husband and a stillborn child. Without the domestic responsibilities that most women of this time faced, Hamilton was able to nurture her artistic talent, studying in European art schools, teaching, and hosting exhibitions both abroad and at home.

By 1918, Hamilton was an experienced artist and longed to return to Europe, where she had spent many years studying. She applied to the Canadian War Memorial Fund, only to have her request denied, as women were not allowed access to the front.

Undeterred, Hamilton eventually found support through the Amputation Club of British Columbia and received a commission to paint the battlefields of France and Belgium. For close to six years, she was one of few Canadian women to experience first-hand the destruction of the front lines — setting up her easel between shell holes and staying in abandoned huts on the battlefields.

As time passed, Hamilton struggled with her finances, keeping her friends back in Canada on standby to sell off her artwork as needed. Lacking proper food and housing, she went through periods of poor health.

Despite these challenges, she was determined to keep going. She wrote, “To have been able to preserve some memory of what this consecrated corner of the world looked like after the storm is a great privilege, and all the reward that an artist could hope for.” From 1919 to 1922, Hamilton produced over three hundred pieces documenting First World War battlefields; she gave most of them to Canada’s national archives in 1926.

Building on the work of their late colleague Angela Davis, Young and McKinnon have written a rich biography that is deserving tribute to Mary Riter Hamilton. Their research is thorough and uses a variety of sources — including Hamilton’s artwork, official and personal correspondence, newspaper articles, and exhibit reviews and critiques — to piece together her life. The book includes colour prints of some of Hamilton’s best-known work.

No Man’s Land is a fascinating read and an important contribution to our understanding of war and commemoration, the professionalization of female artists, and, more broadly, the experiences of women in the early twentieth century.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement