After Victory: The Legacy of the Necessary War

The end of the Second World War in 1945 — first in Europe on VE day, May 8, and then finally in Japan on August 15 — was a time of relief and joy for some, unending pain and trauma for others, and for all a period of turmoil and uncertainty.

Canada’s greatest challenge was to move from an economy geared to war to one that could provide the goods for peace. It did not have to rebuild its bombed cities, as did most of Europe. It did not have to deal with the legacy of an invading army passing through its country like a swarm of locusts, destroying everything in its path.

And yet six years of war left Canadians anxious about many things, especially a feared return to the kind of economic depression that had marked the 1930s. Canada had helped to win the war; now it had to win the peace.

The aftermath of the First World War had shown how not to move from war to peace. In late 1918, the Dominion’s munitions factories ground to a sudden halt, leaving tens of thousands of people without paycheques.

Economic hardship, runaway inflation, and sorrow for the fallen were exacerbated by the terror of the Spanish flu that killed some fifty thousand Canadians. After defeating the German kaiser’s armies, several hundred thousand soldiers came home in 1919 looking for jobs that were not there. With little state intervention, veterans were left to fend for themselves.

A generation later, under the cabinet of Liberal Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King — and especially the firm hand of Minister of Reconstruction C.D. Howe — the government eased industry out of war production and into civilian goods.

It also offered inducements in the form of tax cuts, monetary incentives, and the sell-off of government assets at low prices. These steps went a long way toward ensuring that Canada did not slip back into crippling financial depression.

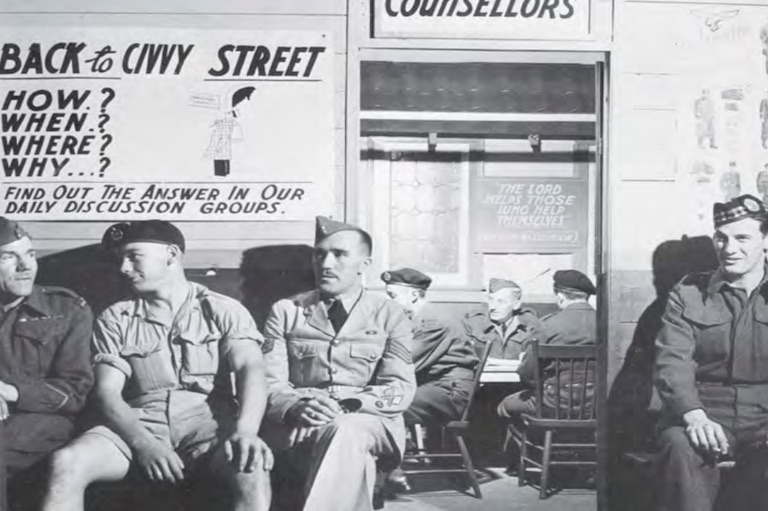

Widespread unease that unemployment would bring mass discontent and unrest prompted the creation of a series of programs for the one million veterans who were returning to civilian life. There was also a desire to reward those who had served during the war and to ease their transition to peace.

Prime Minister King, whose beloved nephew with the same name was killed during the Battle of the Atlantic, believed in “giving first place in everything to the man who was offering his life voluntarily for the service of his country.” He lived up to his promise, including to the fifty thousand women who served in the armed forces.

Cash payments were issued for length of time in uniform (on average about five hundred dollars per person), along with retraining programs and loans for purchasing farms, starting businesses, and buying homes.

Where access to universities before the war had been denied to all but the most affluent — except for the occasional scholarship winner — now it was opened to veterans. Enrolment more than doubled from pre-war years as universities expanded rapidly to meet the rush of fifty-four thousand new veterans turned students.

One of them, Flight Lieutenant Douglas Humphreys, was unsure of his own future at the age of twenty-five. His enrolment at the University of Toronto was, in his words, “a dream that was finally coming true.” He settled into his studies and believed that “the future would take care of itself.” It did — for him and for hundreds of thousands of others.

This state support — in the form of the many programs, grants, and educational opportunities — became known as the Veterans Charter. And yet not all veterans prospered in the immediate postwar years.

Tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, seem to have known little about the charter’s programs. And Indigenous veterans, who numbered more than 4,300, faced systemic barriers if they returned to reserves. There they were usually physically isolated, and Indian agents often blocked them from participating in the programs.

But most returned men and women were not abandoned to their fate. The Veterans Charter was a legacy that would shape the postwar years in Canada. As one veteran remarked: “There were opportunities for everyone.”

The state also sought to care for wounded veterans, of which there were around fifty-five thousand — with more than half of them badly injured and requiring prolonged medical assistance. While there was no universal medicare coverage in Canada, the government did provide health care for veterans similar to what had been offered after the First World War.

Dozens of new hospitals and treatment centres staffed with doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, and other specialists treated thousands of wounded veterans.

With some two thousand Canadians suffering wartime amputations, there were prosthetic limbs to be fitted and glass eyes to be issued. Grafts were needed to repair burned, rubberlike skin.

Horribly disfigured veterans underwent multiple operations so that they might once again return to society. While many veterans recovered from their wounds, others never did. The latter lived in hospitals for the rest of their lives.

Other combatants appeared to have escaped without a trace of wounds. However, wartime trauma sometimes lurked just beneath the surface, rising up to torment without warning. Sam Roddan, a Canadian officer who served with a British regiment, the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, experienced the grinding warfare of northwest Europe.

Under constant stress and strain, he saw men killed and maimed. The trauma made him feel like he was losing control over himself. “It creeps up on you when you are least prepared,” he wrote. “It dries out your mouth. It gets into your bones and muscles. It’s like dry rot in the brain and heart.”

Roddan eventually broke down from the combat stress and was sent home. Although he went on to a career as a teacher and a writer, his lingering mental wounds traumatized him for decades, long before society came to understand post-traumatic stress injuries. He wrote in 1989, “I draw close to those around me, as though to make room for absent comrades now part of history.”

A new social-security net emerged from the war, thanks to Canada’s wartime leader, who rarely led from the front but had well-honed political instincts. King had served as prime minister since 1935, and his cautious hand must have impressed Canadians during the war, since they again chose his party in the June 1945 election.

His Liberals won in part because of their measured wartime leadership. They ensured that the passions of English Canada did not lead to the full alienation of French Canada, such as accusations of being traitors to the cause, as had occurred during the First World War.

While there were wartime regional and linguistic tensions, and a stronger anti-war movement in Quebec than in any other province, especially after the limited conscription in late 1944, the wounds to national unity were not as deep.

There were other fault lines, however. The War Measures Act had allowed for censorship, imprisonment without trial, and deep intrusion by the state into the lives of all Canadians. But it took some time for this legacy of the war to emerge as a cautionary lesson.

Most egregiously, there was little talk after the war about the harsh treatment of the twenty-three thousand Japanese Canadians and Japanese nationals who had been forcibly relocated from the west coast in 1942.

Branded as enemy aliens, they were herded into isolated camps while their goods, homes, and businesses were sold off at criminally low prices. It would take that group several decades to address the historical amnesia around its unjust treatment.

The stronger state had been necessary to fully prosecute the war, but Ottawa did not relinquish all of its powers once the war ended. In the postwar years, the number of public servants continued to grow, with preferential hiring for veterans. More programs were created and administered to aid Canadians in the uncertain time.

Canadians seemed to support a greater role for the state in their daily lives, with one wartime Gallup poll revealing that seventy-one per cent of respondents wanted to “see great reforms in the country after the war.”

Among the programs introduced in 1945 was the “baby bonus” — or family allowance. Issued on a sliding scale according to age, the bonus averaged about seven dollars per child per month. In the years to follow, further changes to federal tax collection and a more interventionist state implied that citizens would be cared for from cradle to grave.

All of this was welcomed by Canadians, although it would forever alter the nature of the citizen and the state — with an expectation of care in its best sense and dependence in its worst.

A new Canada emerged on other fronts, too. Almost fifty thousand brides who had married Canadian soldiers stationed overseas arrived between 1945 and 1946, along with some twenty-two thousand children. The war brides were spread across the country and became a living legacy of the war.

They and their husbands faced many challenges as they moved from the stark excitement and desperation of the war years to the beauty and grind of postwar life. Thirty years later, war bride Peggy A. O’Hara wrote of their impact as a group: “There must be literally hundreds of stories, humorous, exciting, charming, and, yes, sad too, that took place when English war brides came to this country.”

Most wartime marriages survived, but some didn’t, contributing to a growing divorce rate in society as a whole. Given that divorce was almost unknown before 1945, this development signalled how the traditional view of marriage had been fundamentally shaken, along with so much else in Canadian society.

With savings built up from ten billion dollars in wartime bonds, service personnel payments, and few opportunities to buy commercial goods in wartime, people were ready to shop.

After victory, they purchased new washers, furniture, cribs, and other goods as the first wave of the baby boom — more than a million births between 1945 and 1950 — washed over the country.

However, housing was in short supply. In 1946, it was estimated that at least four hundred thousand homes were needed. The Canadian Legion — which had been formed from several veterans groups in 1926 — pressured all levels of government to act. “It is nothing less than a moral right,” argued the Legion, “that a man who has served his country shall, as far as possible, be re-established in society.”

In response, King’s cabinet created the Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation. This body, which still exists today with a slightly different name, disbursed several hundred million dollars to stimulate home building.

Small houses for young families went up quickly in new suburbs across the country. While many of these postwar dwellings have not survived into the twenty-first century, suburban development remains a fixture of Canada’s cities.

The industrial workplace also went through a major shift. During the war, men and women on the home front produced sixteen thousand aircraft, 8,655 ships and small vessels, more than eight hundred thousand military trucks, and more than 1.7 million small arms.

As one wartime poster commanded, “Every Canadian must fight.” It included an image of two men — one in military uniform and another, in workers’ overalls. The war production at home was as important as the fight overseas in the unlimited war effort.

The totality of the effort and the importance of wartime industry strengthened organized labour, which had been virtually destroyed during the Depression years.

Strikes became increasingly common from the midpoint of the war. The labour unrest was due in part to the federal government’s wage and price controls. While these controls made Canada more successful in checking inflation than any other country, workers saw that little of the newly created wealth was being passed on to them.

The wartime labour force had included 1.2 million women, including 261,000 who did weapons-related work. Another 50,000 women served in uniform.

Forced to compromise, the cabinet passed Order in Council PC 1003 in February 1944. The Wartime Labour Relations Regulations were a momentous win for labour, as they guaranteed collective-bargaining rights, recognized unions, and outlawed unfair work practices.

While labour peace remained elusive, the regulations built a firm foundation upon which future generations would continue to negotiate.

The wartime labour force had included 1.2 million women, including 261,000 who did weapons-related work. Another 50,000 women served in uniform.

Many of these women experienced new-found freedom as they answered the call to step up, received a steady paycheque, and took pride in their contributions.

However, the RCAF’s Women’s Division, the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service, and the Women’s Canadian Army Corps were all demobilized at war’s end, with some exceptions for military nurses. At the same time, most of the women who had entered the workforce were forced out of their jobs to make room for returning men.

How should their wartime contributions be viewed? Some were disappointed at being cast aside after having contributed to the victory. Others were proud of their service and of being an inspiration for their daughters who, as the next generation, would stride forward demanding greater equality.

The million Second World War veterans joined about half a million veterans of the First World War in upholding powerful ideals of camaraderie. Among veterans organizations, the Canadian Legion was the most influential.

While many who served in the Second World War were still in their twenties in 1945, and so they often did not define themselves as veterans, they slowly moved to the Legion and other regimental or unit associations over the coming decades.

Governor General Georges Vanier, a veteran of two world wars, wrote about the enduring value of “friendship made on the battlefield.” He said, “the links that are forged in the heat of battle between men who have fought and suffered together outlive war and may very well do more than anything else to establish order in our troubled world. Only those who have been through war can appreciate the curse and realize what a blessing peace is.”

In the postwar years, veterans looked like other Canadians, except for the visibly wounded. Yet they were different. They were marked by war and by their shared service. As a group, they were non-partisan, with the Royal Canadian Legion and other similar organizations pursuing the goal of ensuring that veterans had sufficient state support in the form of pensions, programs, and care.

Veterans also strained against the fading of the war from social memory; they did not want their comrades’ sacrifices to be forgotten.

They sold poppies, marched on Remembrance Day, and reminded Canadians of the importance of the Second World War and other conflicts where Canadians paid the ultimate price in defence of liberal and democratic ideals.

As the war changed much within Canada’s borders, it also forced Canada to think about its relationship with other nations. But the cautious and tired King had made little impact at the inaugural United Nations conference in San Francisco in April 1945.

He was fearful of commitment and preoccupied with domestic harmony, even though Canadians had revealed in a January 1945 Gallup poll that they were overwhelmingly in favour of membership in a body like the United Nations. (Now ubiquitous public-opinion polling began in Canada during the Second World War.)

In this the public agreed with some of the best and brightest of the country’s diplomats, who sought a more weighty role for Canada on the world stage.

While King did little to advance Canada’s external role from 1945, much changed after he retired in 1948. King hand-picked Louis St. Laurent to succeed him as Liberal leader and prime minister.

St. Laurent and his minister of external affairs, the internationalist Lester B. Pearson, pushed to have Canada face outward. “We have learned that we don’t get peace just by winning a war,” wrote Pearson in 1944. “If we are going to get peace and keep it, we will have to rethink our way out of the blunders and betrayals that led to World War Two.”

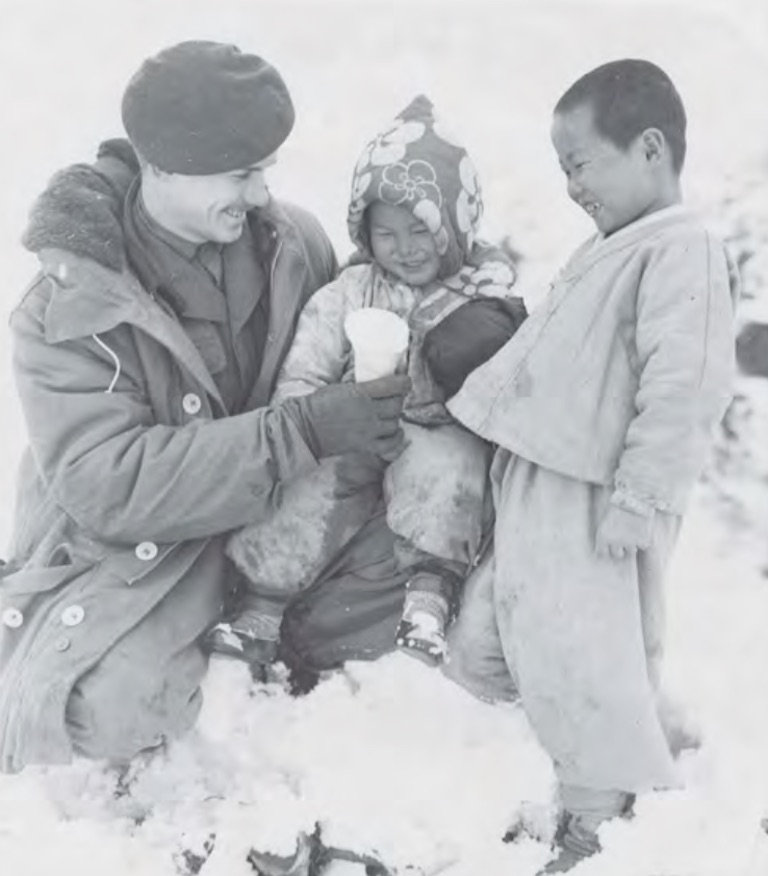

Pearson became an invaluable leader over the next two decades, positioning Canada as a middle power focused on promoting global trade and stability. He was also willing to send armed Canadians to fight wars and to intervene to ensure peace.

As a shrewd Cold War warrior, Pearson understood that the fragile search for stability could be achieved and kept through many means, including by negotiation and compromise as well as by maintaining a robust military and by forging military alliances.

Before St. Laurent took power, the world was already divided between capitalists and communists. A turning point had taken place in Ottawa in September 1945, when cipher clerk Igor Gouzenko defected from the Soviet embassy. Fearful of returning to the Soviet Union, where he believed that he would be imprisoned or executed, he handed over information that revealed a secret spy network operating in Britain, the United States, and Canada.

It was proof that the Soviets continued to work towards bringing down the capitalist system. After initial hesitation regarding what to do with the explosive news, Canada shared the information with its allies.

There was no escaping the spectre of communism. Canadian political leaders, diplomats, soldiers, and citizens would cautiously find their way forward in the complex field of international relations, building up a stellar diplomatic corps, joining NATO as a founding member, sending Canadian forces into war beside its allies in Korea in 1950, and being aligned with the Western world in defending democratic ideals, no matter how imperfectly it was done.

The Second World War set the stage for the Cold War to follow, and Canada would spend the next four decades navigating cold, proxy, and hot regional wars.

In addition to the Cold War that set East against West, a new decolonization movement pitted North against South. The Second World War had revealed the rotten structures that had been used for centuries to perpetuate colonialism.

The humiliating defeats inflicted by the Japanese on the colonial empires of the Dutch in Java and Indonesia and the French in Indo-China, as well as in large parts of the British Empire, had revealed how fragile colonialism was as a governance system. Strong nationalist movements in wartorn countries rose up to demand autonomy.

Canada was not directly involved in these struggles, although a no longer so great Britain called upon Canada for aid amid this reordering across the globe. It came in the form of an enormous loan, which would be, in the words of economist John Maynard Keynes, a “financial Dunkirk.”

King’s cabinet was not feeling generous, rightly believing that Britain had taken Canada for granted during the war. But King knew that Canadians had strong ties to Britain and would demand that aid be sent.

The cabinet eventually agreed in early 1946 to a low-interest loan of $1.25 billion — more than one tenth of Canada’s gross national product.

This was in addition to more than $2 billion in interest-free loans, munitions, and food that Canada had sent to Britain during the war under the Mutual Aid Program. Canada became a wealthy nation, with its economy expanding from $11.8 billion in 1945 to $18.4 billion in 1950.

Britain’s weakness gave Canada greater space in which to exert its autonomy. For instance, King’s adroit manoeuvres and his positive relationship with American President Franklin D. Roosevelt led to the Hyde Park Declaration of April 20, 1941.

This was a financial arrangement with the United States that helped Canada to sell its goods south of the border and thereby also to provide war materials to Britain. After the war, Canadians turned willingly — too willingly, some warned—to the new, increasingly dominant United States.

Members of Canada’s wartime cabinet were not unaware of the deepening entanglement of the two countries. It had watched warily during the war as Americans garrisoned troops in Newfoundland — which was not yet a part of Canada — by the thousands, sending warships and patrol aircraft to create a forward defence for the Battle of the Atlantic.

Canada followed suit by ordering its own troops and equipment to the crown colony, fighting together with the Americans against their joint enemy but also to ensure a strong Canadian presence.

Canada had courted the separate island colony unsuccessfully since before 1867, but worried that the Americans, with their money and energy, would eventually entice the fiercely independent Newfoundlanders to join the republic. While the war stimulated the colony’s moribund economy, Newfoundlanders did not embrace the United States.

Instead, they joined Canada in 1949. One of the incentives was the extension of Canada’s generous veterans benefits to the 2,327 Newfoundlanders who served in the Second World War and to the thousands of other survivors of combat in the Great War.

Another legacy of the war was the network of airfields and bases that had been rapidly constructed as part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP). Far from the Luftwaffe’s bombs, Canada had agreed in December 1939 to host the training plan. At the program’s peak there were 107 schools and 184 ancillary units at 231 sites across the country.

More than 131,000 Allied aircrew were trained in this noteworthy Canadian contribution to victory; and after the war, as Britain floundered in debt, Canada swallowed most of the plan’s cost — more than $1.6 billion.

The BCATP left behind an infrastructure for an emerging airline industry, connecting the vast country in new ways and paving the way for the pioneers and entrepreneurs of Canadian aviation.

The Alaska Highway also became a lasting legacy for Canada, while temporarily threatening its sovereignty. The Americans built the road in response to the wartime threat of a Japanese invasion.

Canada agreed to allow a force of more than twenty-five thousand American military engineers, soldiers, and contract workers to build the 2,300-kilometre highway (later expanded) from Dawson Creek, B.C., to Big Delta, Alaska. The road was completed in eight months from 1942 to 1943, through some of the most difficult terrain in North America. It was a truly incredible feat.

It took some time for the federal government to realize the implications of the highway for Canadian sovereignty. It didn’t help that American military personnel occasionally answered the phone with an opening greeting of, “Hello, army of occupation.”

The Canadian cabinet eventually insisted on paying for Canada’s share, fearful of the precedent that might be set. At the cost of $123.5 million, it was a pricey way to exert autonomy, although the road was an important legacy from the war that connected parts of northern Canada to the more populous south.

The war led to other joint Canada-United States operations, especially the combined defence of North America. An early co-operation scheme between King and Roosevelt, agreed to on August 18, 1940, created the Permanent Joint Board on Defence, a body that guides hemispheric security issues to this day.

The war drew Canada into the American orbit, where it had been pushed by Britain’s weakness and the wartime trade and security issues that continued into the postwar years.

Navigating the complexities of having the United States as a neighbour became one of the preoccupations of all Canadian politicians in the post-1945 period.

The war also strengthened Canadian identity. As in the Great War, Canadians fought together in their own units, under their own commanders, with their own symbols like the maple leaf, albeit within the Allied command structure.

During the Second World War, there were identifiable Canadian formations, including 6 Group, Royal Canadian Air Force, in Bomber Command; the Royal Canadian Navy; and the First Canadian Army. Often, Canada’s squadrons, ships, and regiments were linked back to communities in Canada, fostering bonds of identity and pride, with corvettes named after cities and regiments drawn initially from specific geographical areas.

“When we went overseas, for the first time in our lives we felt that we represented Canada,” reflected Norman Penner, a wartime signaller and later a professor of political science at York University.

“In Europe the badge on our shoulder meant something. The nationalism of these Canadian boys was a direct result of their participation in the war.... It was widely recognized that we had taken our place among the soldiers of other nations and helped to win this great world struggle.”

The nationalizing effects of the war inspired Canadians, proud of their independent service and significant contributions to the Allied victory, to carve out a separate identify from that of the British and Americans. As one veteran remarked years later, “We lost our inferiority complex.”

Certain Canadian cultural products distinguished the Canadian war effort. The Maple Leaf reported on and highlighted Canadian stories in its newspaper pages, while combat cameramen from the Canadian Film and Photo Unit supplied footage to be used in the Canadian Army Newsreels and at home within National Film Board productions.

Canadian journalists reported stories for those at home, while service historians created records for future generations. Photographers close to the front snapped shots of all three services, and official war artists like Lawren P. Harris, Charles Comfort, and Molly Lamb Bobak left a moving legacy on canvas.

Variety shows like Meet the Navy and the Canadian Army Show, as well as many bands and performers, reinforced Canadian culture, albeit of a lowbrow form.

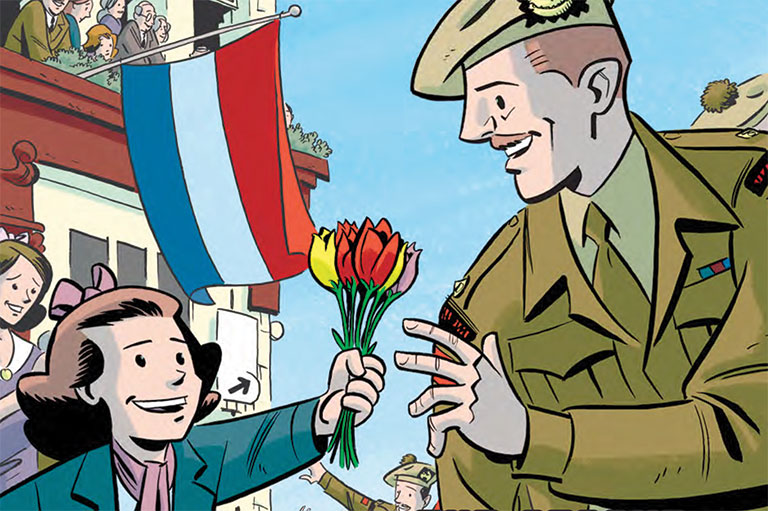

Perhaps even lower — but highly appreciated by the soldiers — were cartoonists like Merle Tingley, Les Callan, and William “Bing” Coughlin, who depicted Canadians in the field. Much loved stand-up comics Johnny Wayne and Frank Shuster made jokes that poked fun at discipline, food, and almost anything else that rankled the rank and file.

These artists helped to foster a distinct Canadian identity and created many of the cultural products that would allow future generations to better imagine the national war effort.

The need for a distinctive Canadian citizenship also emerged from the war. One of King’s junior cabinet ministers, Paul Martin (father of future Prime Minister Paul Martin), had come to that conclusion after seeing the graves of men from his riding in Windsor, Ontario, who had served in the Essex Scottish Regiment and had been among those who were cut down at Dieppe, France.

These Canadians who fell in defence of democratic values, he believed, should be recognized as Canadians and not as British subjects. Martin pushed through the Citizenship Act in 1947, thereby creating Canadian citizenship.

There were other changes, including the opening of Canada’s borders to new immigrants, most of whom had been affected by the war. They included tens of thousands f Dutch who felt strong ties to their liberators, Jewish survivors of the Holocaust, and some five thousand Polish soldiers who had fought for the Allies and whose homeland had been abandoned to the communists.

Within a few years there were even German immigrants. One was Gunter Lutzmann, a U-boat wireless operator who had been captured and sent to a prisoner of war camp in Petawawa, Ontario, during the war.

Like the other thirty-four thousand German prisoners in Canada, he returned to a shattered homeland after the war. When he immigrated to Canada in 1952, his motivation, as he said decades later, was that it was “the best place to raise a family.”

While it must have been strange for many Canadians to see Germans moving to Canada, the broken Germany, divided into east and west, seemed fated to wallow in the war’s bitter defeat. But, in less than a decade, West Germany was rearmed and a part of the NATO alliance in the Cold War.

This would not be the last time that Canada was forced to make hard choices in standing by new allies who had once been enemies. And, while Canada sought to be an honest broker on the world stage, it was entwined with Western allies, both in for- mal military alliances and in ideological beliefs.

All the while, Canadians learned to live in the nuclear age, with the 1945 mushroom clouds above the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki continuing to loom in the global consciousness.

As the years passed, the new postwar social-security net became more encompassing, and more expensive, with crippling debt arriving in the early 1990s.

Some dark and buried legacies of the war also worked their way to the surface of historical awareness. A suppression of civil liberties under the War Measures Act during the war years took place again during the October Crisis in 1970.

This led some of those seeking greater autonomy in Quebec, as well as terrorist groups like the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ), to invoke memories of oppression during the Second World War.

These new ways of looking at the past often diluted the memory of the contributions of the tens of thousands of French-speaking Canadians who had enlisted in the war against the fascists.

The wartime forced relocation of Japanese Canadians also took decades to come to light. By the late 1970s, the descendants of those whose civil liberties had been trampled began campaigning for redress. This culminated in a formal apology and financial restitution in 1988.

Canadians came to see that, in the war for democratic ideals and to free the oppressed overseas, the wartime Canadian state had also oppressed some of its own citizens and had curtailed civil liberties for all.

The wartime pain over the loss of forty-five thousand Canadians killed in uniform dimmed over time, but it remained a jagged scar for countless people across the country who had lost close family members.

One of them was Jean Margaret Crowe, whose husband died during wartime RCAF operations. She wrote about her grief, loneliness, and envy for those who were able to move on: “Nobody ever asked us what it was like to be a widow at 22 or 23. Nobody gave us any counsel.”

After the victory, and during the building of a new Canada, there were parents who had outlived their children, widows who never remarried, children who grew up not knowing a father, and veterans who struggled with physical and mental injuries. Their war never ended.

Canada’s colossal contribution to the Allied victory in the Second World War led to unexpected changes across the country, from the emergence of the social-security state to advances in culture, from being more intensely tied to the United States to a new willingness to engage with the world. Canada moved forward as a wealthy nation, more certain of what it meant to be Canadian.

From 1945 on, Canadians enjoyed an extended period of growth and change. Canada’s wartime service and sacrifice were not the only reasons for this transformation.

Nevertheless, waging a necessary war against the Nazis and the other fascists had left Canada a very different country.

The world that emerged from the ruins of 1945 was set on a new trajectory, and Canadians — veterans and others — were unsure of what the future held. They would work together to forge their new destiny in the unfinished project that is Canada.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Beautiful woven all-silk bow tie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. This bow tie was inspired by Pierre Berton, inaugural winner of the Governor General's History Award for Popular Media: The Pierre Berton Award, presented by Canada's History Society. Self-tie with adjustments for neck size. Please note: these are not pre-tied.

Made exclusively for Canada's History.

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!