West Pubnico, Nova Scotia: Farming saltwater marshes

Along Nova Scotia’s southwestern shores you can walk the saltwater marshes farmed by the Acadians who first settled in the uplands in the mid-1600s. The changing tides of the sea that provided sustenance also saturated the land with salt, rendering it infertile.

Dykes were built to hold back the sea, but the salt water seeped in through the soil beneath, leaving behind the salt when the tides subsided. Settlers desperate to grow crops faced a challenge — how to keep the fresh water in and the salt water out?

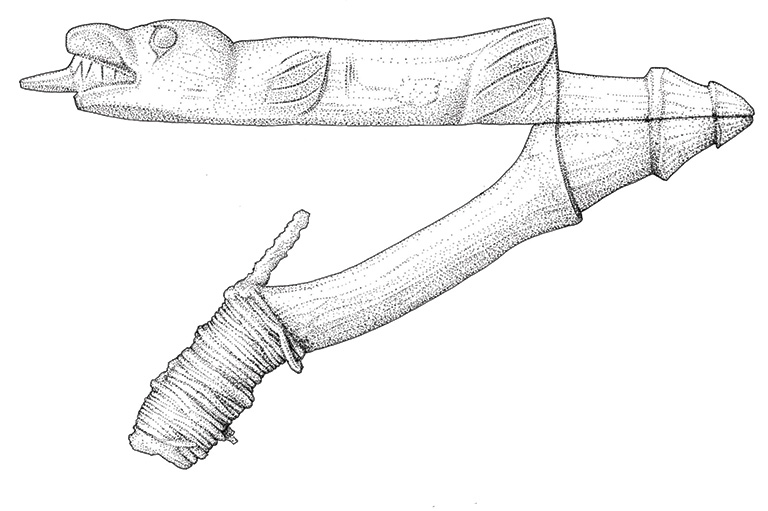

As a solution, the early Acadians incorporated a technology from their home country of France — a sluice box known as an aboiteau.

The simple but highly efficient design consists of two squared timbers laid parallel to form the sides of the box, a roof and floor constructed from planks and a gate at one end that swings open to allow excess fresh water to flow out but swings closed against incoming salt water.

The aboiteaux were buried beneath the dyke at sea level. With constant drainage and the dilution of salt content by rainwater, the land was able to sustain crops within a few years of installation. (Before the advent of milled wood, aboiteaux were built from hollowed out logs using axes and adzes.)

Use of the aboiteaux allowed Acadians to grow ample crops such as hay, wheat and vegetables.

In 1990, residents walking along the beach of Double Island, West Pubnico, Nova Scotia, noticed several boards protruding from the muddy marsh. Four years later they investigated further and found the remains of an aboiteau dating to the late 18th or early 19th century.

In fall of the following year, staff from the Nova Scotia Museum visited the site and made plans to excavate and preserve the aboiteau. A local excavation crew assisted Ted D’Eon, a local pharmacist with an avid passion for history, and archaeologist Stephen Powell, assistant curator at the Nova Scotia Museum.

They removed the covering layers of marsh mud and gravel, photographed the aboiteau and carried it to a trailer to be towed to a nearby garage.

Between three and four metres long and 35 to 40 centimetres wide, constructed of white pine, the aboiteau was severely waterlogged and missing the swing gate and several planks. After cleaning, it was soaked in wood preservative for several months, then dried.

Though existence of the aboiteau is well known in recorded history, few examples of this early Acadian technology survive.

Two other restored aboiteaux dating to the early to mid 18th century are on display at the Grand-Pré National Historic Site at Grand Pré and the North Hills Museum at Granville Ferry, both in Nova Scotia.

To get a glimpse of the West Pubnico aboiteau, visit the Acadian Museum in West Pubnico, Nova Scotia, or visit the website MuseeAcadien.ca.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement