Quiet Crusader

“Book history can never fire the imagination like physical object lessons. No Canadian wants the scene of famous victories — of peace or of war — incorporated within the grounds of some private owner.”— J.B. Harkin, Just a Sprig of Mountain Heather, 1914.

While most Canadians could name some of our National Historic Sites and national parks, very few could name the man behind them — James Bernard Harkin. Known as the “father of Canada’s national parks,” Harkin was also behind the establishment of what today is a related system of 167 National Historic Sites managed by Parks Canada.

Given today’s growing interest in conservation, recreation, and historic site preservation, it seems strange that a man who played such a key role in these areas should be so unknown. Or perhaps not. After all, we are more accustomed to our heroes being sports stars, actors, generals, and scientists — not government bureaucrats.

The way parks and historic sites evolved in this country, as well as Harkin’s position and modus operandi, also contributed to his relative anonymity.

For instance, in the United States, the creation of the National Park Service in 1916 was largely the work of Stephen Mather. The wealthy, gregarious, and well-connected businessman launched a vigorous campaign for public and private support for the parks and made generous contributions from his personal fortune. Much has been written about Mather and there are many features in American parks — such as Mather Point at the Grand Canyon — that carry his name.

In Canada, the parks and historic site systems were largely driven by the efforts of politicians and bureaucrats.

Harkin was the civil servant at the helm of these efforts and, in line with the nature of government service and his own predilection for keeping a low profile, he left little record of his accomplishments.

However, he wasn’t utterly forgotten. One landmark is named after him — Mount Harkin in Kootenay National Park — and his name appears on a commemorative plaque in Banff and on a conservation medal established in 1972.

Harkin was born at Vankleek Hill, Ontario, in 1875, the son of William Harkin, a doctor and Conservative MLA. He grew up under the influence of his older brother William Jr., a political journalist with the Ottawa Journal. At age seventeen, Harkin followed in his brother’s footsteps and joined the newspaper.

He soon rose to the position of city editor, with a seat in the parliamentary press gallery. He reported on the success of Wilfrid Laurier and his Liberals as they began to remake the nation in the wake of their 1896 election victory. His writing skills and knowledge of politics soon brought him to the attention of Laurier’s western lieutenant, Interior Minister Clifford Sifton, who approached him about becoming his political secretary.

After passing his civil service examinations, the twenty-six-year-old Harkin began government service as a second-class clerk on December 2, 1901. His sensitive position required him to work behind the scenes, establishing a trait that would become a hallmark of his entire career. He soon rose to the position of chief secretary. When Edmonton MP Frank Oliver succeeded Sifton as minister in 1905, Harkin continued in his post and became Oliver’s foremost troubleshooter.

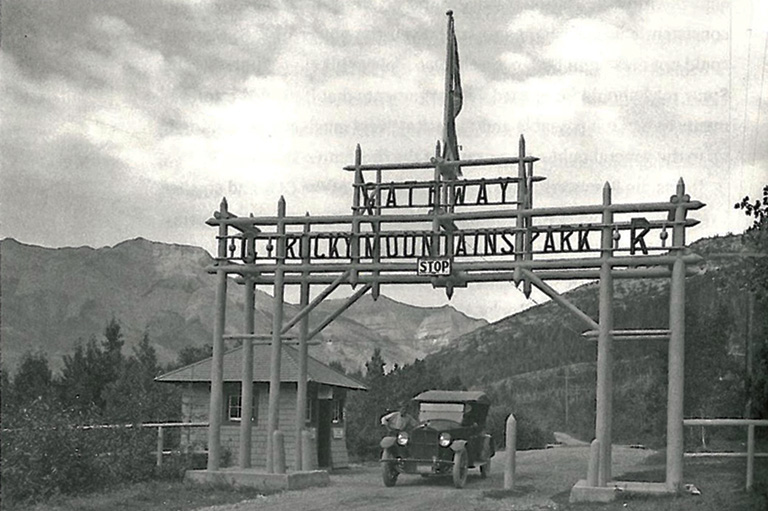

One of Oliver’s many responsibilities was the Department of the Interior’s haphazard collection of parks and reserves. This began with the creation of Rocky Mountains (later Banff) Park along the new CPR line in 1887. Scenic reserves around Mount Stephen near Field, British Columbia, and Rogers Pass in the Selkirks (later Yoho and Glacier national parks) were soon added, along with a small forest park at Waterton Lakes, Alberta, created in 1895 and a large elk preserve east of Edmonton established in 1903 (later Elk Island National Park). In 1907, Oliver himself spearheaded the creation of the large Jasper Forest Park along the lines of two new railways near the headwaters of the Athabasca River.

The growing number of holdings and the lack of administrative oversight of them had by 1911 led the minister to sponsor a bill—the Dominion Forest Reserves and Parks Act — putting the five parks under the auspices of a new Dominion Parks Branch. Oliver asked Harkin to head it. Despite professing to know “nothing about parks or what would be expected of me,” Harkin became the commissioner of the Dominion Parks Branch on August 10, 1911.

Harkin faced several challenges. The new legislation said parks could only be part of forest reserves, yet the existing reserves were so seriously reduced in size that they were almost irrelevant. Furthermore, he realized that in order to strengthen and increase the size of the nascent park system — indeed, even to have it survive — Canadians had to believe parks were important.

To accomplish this, he utilized some thinking then current in Canadian social and economic life — an emerging belief that nature was not something that needed to be beaten back in mankind’s quest for progress, but was something that had humanizing elements that could restore health and help soothe city-worn nerves. Harkin became convinced of this after experiencing the Rocky Mountains himself for the first time at an Alpine Club of Canada camp in 1912.

“People sometimes accuse me of being a mystic about the influence of the mountains,” he wrote later. “Perhaps I am. I devoutly believe that there are emanations from them, intangible but very real, which elevate the mind and purify the spirit.”

The act indicated that parks existed “for the benefit, advantage, and enjoyment of the people of Canada,” and Harkin argued this was best achieved through “the pure, wholesome, healthful recreation of the great outdoors” that national parks offered.

Another challenge Harkin faced was the political expectation that parks would pull their own weight — all of the Department of the Interior’s activities in the West were supposed to contribute to the national purse. After carrying out research into the value of tourism to many European countries’ economies, he determined that tourism could provide the necessary revenue to parks. Thus he became a strong proponent of making parks accessible to what was then a new technology—the automobile. Roads and drives soon became the focus of much of the Parks Branch’s early development work.

Harkin developed a trademark ability to coin memorable phrases, claiming that the parks system would produce “dividends in gold and dividends in human units.” In 1920, his approach bore fruit when soon-to-be prime minister Arthur Meighen supported increased funding for parks. Harkin recalled, “the appropriations vote passed without further objection and the economic value of the parks was thenceforth established.”

Harkin had by then already scored some victories. In 1913, he succeeded in having an amendment passed to remove the necessity for all parks to be in forest reserves. And in 1914 a decision to decrease the size of Rocky Mountains, Jasper, and Waterton parks was reversed. The same year, Harkin produced Just a Sprig of Mountain Heather, at once a beautiful souvenir for park visitors but also a document of Canada’s park policy.

Central to the policy was his call for four distinct types of parks — “scenic parks, historic parks, animal parks, and parks located specially for congested areas of population.”

Scenic parks were already well established, but they were all in the West, where their creation was made easier because much land was still under federal control. To create parks near large population areas, he needed to expand the system to Eastern Canada.

It was in the drive to accomplish this that Harkin first identified a role for the “historic parks” he mentioned in Sprig. He had become an early member of the Historic Landmarks Association of Canada (later the Canadian Historical Association), formed in 1907 as an offshoot of the Royal Society of Canada to co-ordinate interest in heritage preservation and commemoration.

Among the association’s goals were efforts to develop the Plains of Abraham in celebration of Quebec’s tercentenary in 1908, as well as plans to do an inventory of significant historic sites across Canada. However, nationalist rivalries all but paralyzed the organization. This provided Harkin with an opening to fill the breach.

“There are many places of historic interest, poorly marked or not marked at all,” he said in a 1913 report. “While it is somewhat out of the sphere of national parks to deal with the marking of battlefields, it is most desirable from a national standpoint that such should be set aside as national reserves and that the ruins, old forts, old towers, and such, holding historic associations, should be preserved.”

He went on to say that these historic spots “should be used as places of resort by Canadian children who, while gaining the benefit of outdoor recreation, would at the same time have the opportunity to absorb historical knowledge under conditions that could not fail to make them better Canadians.”

Fort Howe in Saint John, New Brunswick, was the first location to be designated as a national historic park. This came about largely due to the efforts of Mabel Peters, president of the Playgrounds Association of Saint John, who wrote to Harkin of unsuccessful local attempts to turn Fort Howe into a park and playground. The fort had been built during the American Revolutionary War to protect the harbour and it subsequently played a significant role for the United Empire Loyalists and in the founding of Saint John in 1783.

Harkin immediately recognized an opportunity for marrying the value of outdoor recreation for Canadian children with the marking and preservation of historic sites.

Fort Howe also filled the goal of being located close to an eastern centre of population. It was established as a national historic park by Order-in-Council on March 30, 1914. The dedication of Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, as Fort Anne Historic Park followed in 1917.

At the same time, Harkin worked to create the other types of parks mentioned in Sprig. He formed an animal division and began building on the work of earlier parks officials to preserve the largest, and one of the last-remaining, bison herds at Buffalo Park, near Wainwright, Alberta. Many of the bison were later shipped to Wood Buffalo National Park, created in 1922 in the Northwest Territories.

The threat to another declining species in the West, the pronghorn antelope, was addressed with the dedication of three antelope parks — Wawaskesy, Menissawok, and Nemiskam — in southern Alberta and Saskatchewan in the early 1920s.

Harkin eventually became responsible for all wildlife on federal lands, which led to his involvement in the 1917 passage of the Migratory Birds Convention Act that confirmed an international treaty with the United States. The branch began setting up bird sanctuaries and in 1918 created one of Canada’s first national parks based on bird protection at Ontario’s Point Pelee on Lake Erie.

After the First World War, Harkin continued creating new parks in the West. One success he particularly savoured resulted from his efforts at seeing through the completion of a road undertaken in 1912 to connect Banff with the interior of British Columbia. The road provided a tourist route from the West Coast and the United States.

When work languished during the war years, Harkin and road promoter Randolph Bruce approached the minister with a proposal that the road be completed by the federal government in return for the province providing a right-of-way extending five miles on either side. In 1920, Kootenay National Park was created from these lands. Harkin regarded its establishment, along with the completion of the Banff Windermere Highway in 1923, as among his greatest achievements.

Meanwhile, in 1919, Arthur Meighen — who was then minister of the Interior Department — was under pressure to preserve important Canadian historic sites. He turned to Harkin as the only bureaucrat with experience in the field.

Harkin proposed the creation of an expert board that would make recommendations and be supported by existing government machinery under the Parks Branch. This resulted in the creation of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, with a membership of five respected historians and Harkin as secretary.

At its first meeting in October 1919, the board decided to carry out a survey of Canadian historic sites. It identified 547 sites in its first few years, but due to rivalries in its membership — the historians tended to promote their own particular interests or region, leading to competitiveness and rancour — and lack of funds, the board’s initial accomplishments were limited.

In fact, only a year after its first meeting, one of the board’s disgruntled members was actively campaigning to have it abolished. Harkin, in turn, urged then Prime Minister Meighen to remove the member, saying, “his presence has been productive of nothing but delay and trouble.” However, this didn’t happen until 1923, when a new slate of board members was appointed.

One thing the board agreed on was that only sites of national significance should be marked. A distinctive commemorative plaque was commissioned for this purpose.

In 1921, a new Historic Sites Division was established in the Parks Branch, with Arthur Pinard, a francophone ex-army officer, hired to head it. The first commemorative plaque was installed in 1922 at Port Dover in southern Ontario — now Cliff Site National Historic Site — to mark New France’s claim to the Lake Erie region in 1670. After 1923, progress began with restoration at a few locations, including Fort Chambly, Fort Lennox, Fort Wellington, and Fort Langley.

As it happened, the most extensive work on historic sites took place during the Great Depression. Harkin, who used his own engineering staff to do the planning, convinced the government to create jobs by providing public works funding for rebuilding at Fortress Louisbourg and Fort Beausejour, and for establishing museums at Fort Chambly and Fort Anne.

In what was one of Harkin’s greatest achievements, the wording of the National Parks Act of 1930 identified National Historic Sites separately from national parks. Historic sites were thereby inalterably set on a different course, albeit under the control of the same agency.

Harkin went on to complete his career in parks-building by gaining major parks for the Maritimes — he drafted the legislative framework for the establishment of Cape Breton Highlands National Park in 1936 and Prince Edward Island N ational Park in 1937. But, despite having little time to devote to it, he also remained committed to historic site work until his retirement in 1936.

When he died in 1955, the Ottawa Journal published a front-page obituary referring to him as the “father of Canada’s national parks.” The obituary noted his success at bringing “organization out of the former laissez-faire chaos in establishing the parks.”

The Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada recommended that Harkin be designated a person of national historic significance. In 1958, a commemorative plaque was unveiled at Banff identifying him as “Editor, Public Servant, Conservationist and Humanitarian.”

Perhaps the honour he would have most appreciated came in 1972, when the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society announced the creation of the J.B. Harkin Conservation Award. The Harkin Medal is presented to “keep alive the memory of this exceptional Canadian” and “recognize those who serve the parks with equal distinction.”

Fittingly, its first recipient was Jean Chretien, who was then the minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, in recognition of his work to establish eleven new national parks, including three in the North.

Today there are forty-two national parks in Canada and four national marine conservation areas. And, at last count, there were 956 National Historic Sites, of which 167 are administered by Parks Canada, as well as 648 persons of national historic significance and 417 events of national historic significance.

This makes up one of the most extensive networks of protected places in the world — an impressive legacy left by a man who at first professed to know “nothing about parks.”

Heroes of historical preservation

Historic sites don’t save themselves. It often takes volunteers with a passion for preservation to ensure that historically significant places don’t get demolished, paved over, or otherwise erased. Here are some of the people who have helped save our National Historic Sites.

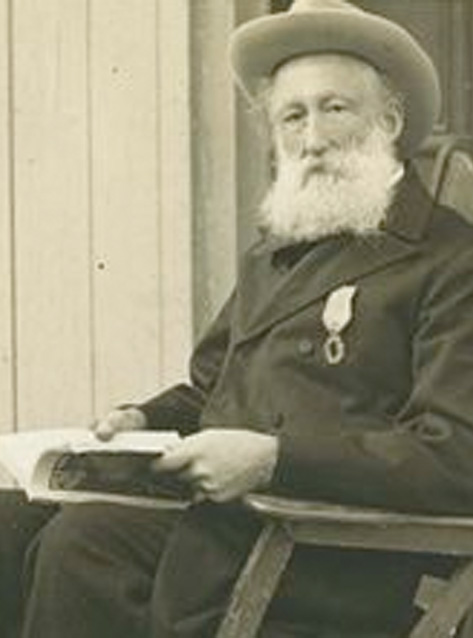

Joseph-Octave Dion (1838–1916)

Fort Chambly’s live-in guardian

Joseph-Octave Dion grew up next to the ruins of Fort Chambly, which was originally built along the Richelieu River to protect the colonists of New France from the Iroquois. Dion moved to Montreal, where he pursued a career in journalism.

When he eventually returned to his hometown, he was alarmed at the fort’s decline — people were removing stone blocks and using them to build homes and fences. Dion began raising funds, organized guided tours, and in 1875 published the first history of Fort Chambly.

He also moved onto the grounds of the fort, where he lived for three decades. The federal Department of Public Works eventually provided funds to overhaul the fort, and Dion became the project’s overseer.

Katharine McLennan (1892–1975)

Louisbourg’s champion

Many people campaigned for the restoration of the Fortress of Louisbourg, but one person who stands out is Katharine McLennan — a member of a wealthy, well-connected family who vacationed on land adjacent to the ruins of the eighteenth-century French fortification.

After returning from overseas service as a nurse during World War I, McLennan took on the task of reviving Louisbourg, collecting French artifacts, establishing a museum, constructing a scale model of the town site, and lobbying for federal recognition of the ruins.

At the time McLennan began her work, the once-mighty fortified town in Cape Breton was reduced to sheep enclosures and had fallen prey to souvenir hunters. Today it is a top historic destination, visited by thousands of tourists annually.

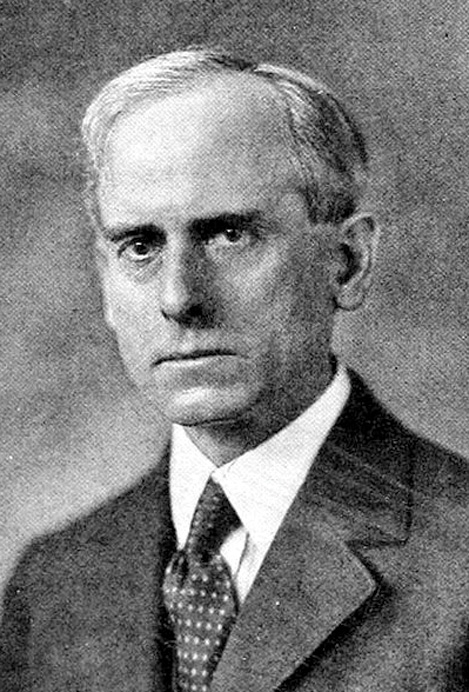

J. C. Webster (1863–1950)

Renowned doctor turned historian

J.C. Webster was a prominent physician who practised and taught in the United States, pioneering new approaches to obstetrics and gynecology.

Plagued with chronic health problems, he abruptly ended his medical work in 1920 at age fifty-seven and returned to his hometown of Shediac, New Brunswick, where he began a second career as a historian. Webster and his wife Alice Lusk Webster, an accomplished art collector, amassed a huge collection of artifacts that was eventually donated to the New Brunswick Museum. Webster also purchased the land under which New Brunswick’s Fort Beau-sejour was situated, later donating it to Canada.

A chairman of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, he spearheaded the establishment of museums at the forts of Beausejour, Louisbourg, Gaspareaux, and Anne.

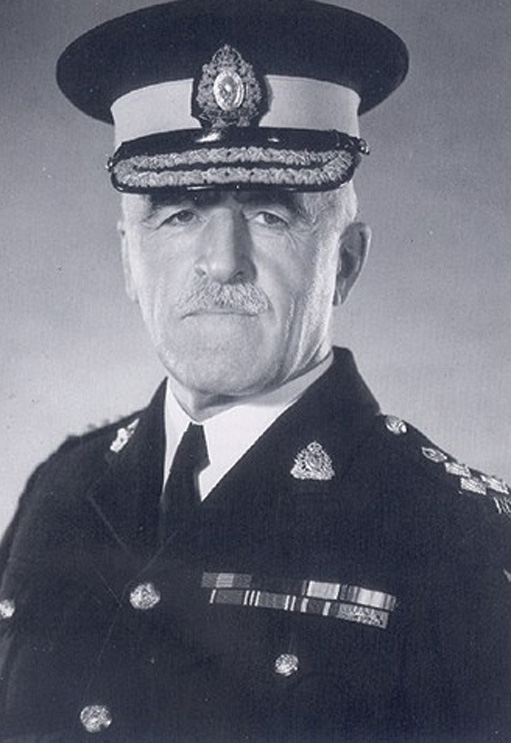

Stuart Taylor Wood (1889–1966)

Visionary Mountie of Fort Walsh

Stuart Taylor Wood developed a passion for mounted police history from his father, Zachary Taylor Wood, who served with the NWMP during the Northwest Rebellion and the Yukon gold rush.

The younger Wood joined the force in 1912, eventually rising to the top post of commissioner. He established the first RCMP museum in 1933–1934.

In 1942, he purchased from a rancher the site of old Fort Walsh — the former NWMP post at the forefront of bringing order to the West. He rebuilt it to conform as closely as possible to the 1875 original and used it to raise the RCMP’s famed black horses.

After Wood died in 1966, the fort was turned over to Parks Canada as a National Historic Site.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Help support history teachers across Canada!

By donating your unused Aeroplan points to Canada’s History Society, you help us provide teachers with crucial resources by offsetting the cost of running our education and awards programs.