Roots: Under the Microscope

In the summer of 2018, news from DNA labs momentarily elbowed politics, celebrities, and sports from the headlines. Connoisseurs of crime detection were fascinated by the capture of the alleged “Golden State Killer,” which was promptly followed by the arrest of a clutch of suspects in comparably ancient cold cases.

Researchers using the everyday tools of genetic genealogy had succeeded in unravelling mysteries that had defied solution for decades. To the press and the public, it all seemed like something from science fiction.

Regular readers of this column might have thought differently. My friend Elizabeth’s struggle to identify her biological father (“Cellular sleuthing,” August-September 2017) was every bit as complicated as a police procedural — and she used many of the same tools and modes of thinking. Similarly, my ultimately successful search for my illegitimate grandfather’s father entailed countless hours of combing through both historical records and DNA-test findings.

So, if researchers can use DNA to identify the biological parents of aging adoptees, the undocumented fathers of nineteenth-century “baseborn” children, or even the details of a century-old “switched-at-birth” hospital error, then it should come as no surprise that they can figure out the identity of a murderer or rapist who left his DNA at the scene of a crime just two or three decades ago.

Advertisement

Actually, as it turns out, it’s quite straightforward. “Already, sixty percent of Americans of Northern European descent — the primary group using [DNA testing] sites — can be identified through such databases whether or not they’ve joined one themselves,” the New York Times reported in October in an article about a newly published study in the journal Science.

“Within two or three years, ninety percent of Americans of European descent will be identifiable from their DNA, researchers found.” Figures for Canada are not known, but they cannot be much different.

CeCe Moore, the professional genealogist who has solved more than a dozen of these cases, predicted to NBC News that we will see dozens of cold cases resolved in upcoming months and hundreds over the next few years. Jay Cook and Tanya Van Cuylenborg, the victims in one of Moore’s earliest cases, were Canadians. There are signs that our police departments have noted these developments, and it is just a matter of time until a Canadian criminal is apprehended.

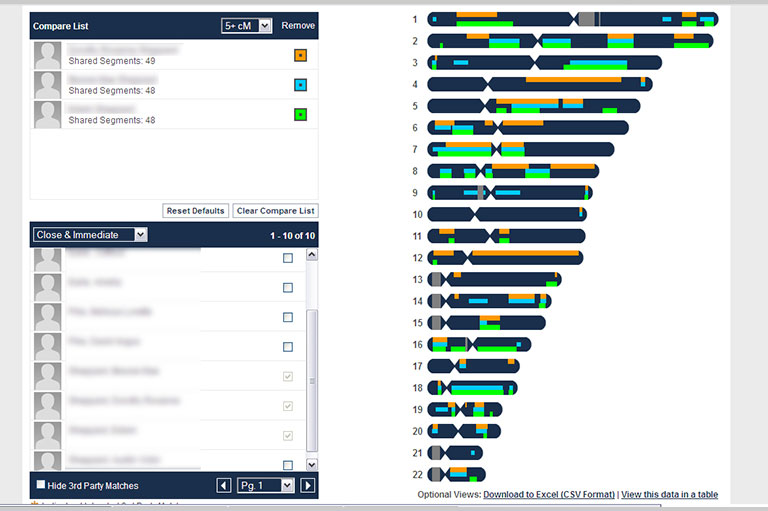

Since 2016, Roots has on four occasions explored the power and limitations of autosomal DNA, which is to say, the DNA you inherit equally from each parent. It’s also the principal genetic tool used in resolving these criminal cases. The advent of genetic cyber-sleuthing is just the most dramatic of the many developments in the science and business of DNA testing that have taken place since this column began.

Here are some others:

- GEDmatch, the open-data DNA website used by Moore and others to identify criminals from their DNA, has changed its terms of service to acknowledge this use by law enforcement. The terms expressly forbid use by police in non-violent crimes. Privacy critics are not happy. I plan to write further about these ethical issues in a future column.

- Two reputable companies (Living DNA and MyHeritage) have joined the three already on the scene (23andMe, AncestryDNA, and Family Tree DNA) in offering affordable, high-quality tests to the genealogical community. (Regrettably, outmoded tests are still being sold to the unwary by other vendors, often using confusingly similar names.) Costs are dropping, and whole-genome sequencing is now becoming an option for the well heeled; within two years, it should be affordable for the average researcher.

- There has been an explosion in the availability of third-party analytic tools, such as GEDmatch, that help researchers to analyze and to visualize their genetic findings.

- The design and interpretation of ethnic, regional, and national analyses etc. (“admixture”) are constantly improving but still have a long way to go. It remains the case that most people who know the origins of all four of their grandparents will discover little that is both unexpected and reliable. However, admixture tests are increasingly helpful in cases of adoption or illegitimacy, where any clue about an unknown parent or grandparent may be the catalyst needed to make a breakthrough.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk necktie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. Made exclusively for Canada's History.