Roots: Lost... and Found!

After graduation, my college roommate moved to his ancestral homeland, Germany. Forty years later, knowing I was keen on family history, he asked if I could locate a copy of his Jewish father’s birth certificate.

Family lore and published sources were unanimous that father, Peter Scherk, had been born in Berlin on September 2, 1910. He fled the Nazis in the late 1930s, escaping the fate of his parents who were murdered by the state in 1942.

No birth certificate survived in Peter’s personal papers, and the relevant Berlin archives had been destroyed during the war. Finding a copy of the certificate was essential if my friend were to exercise his right to claim automatic German citizenship as the child of a Holocaust survivor. This was the only way he could become a German national without having to renounce his Canadian citizenship, a step he was loath to take.

At first I thought the project would be a doddle. Peter Scherk had been an academic of note, the author of sixty research papers. He had studied and taught with distinction at major universities in Germany, the United States, and Canada from the 1930s to the 1980s. Online biographies were consistent in the details of his accomplished life. How hard could it be to document the universally accepted specifics of his birth?

I began by filling in the details. A passenger manifest pinpointed Scherk’s arrival in New York in 1939 with a prior residence in Prague, Czechoslovakia. In the early 1940s, Scherk appeared fleetingly in various American records. And in 1943 he accepted a full-time position on the faculty of the University of Saskatchewan. Good information, but no birth certificate.

Next, it was time for official records. But his U.S. immigration, Canadian immigration, and Canadian naturalization files were identical in one respect: no birth certificate.

Around this time, my friend shared the good news that German authorities had relented and had accepted the overwhelming circumstantial case for Scherk’s birth in Germany. Even so, I was reluctant to give up the chase. What kind of family historian can’t find a simple birth certificate?

The breakthrough came, as it so often does, from studying documents already in hand. Had I extracted every shred of information? Apparently not.

In the passenger manifest for Scherk’s 1939 arrival in New York, I had previously interpreted his travel document “QIV-23984” as referring to a passport or exit visa from Germany or Czechoslovakia.

During re-examination of the manifest, I realized there were printed instructions for logging travel documents: “Prefix number with QIV, NQIV, PV, or RP.” If they were part of a foreign numbering system, why would the letters QIV appear in instructions on an American form?

The simplest explanation was that the permit had been numbered in accordance with an American system and issued by an American authority. Was it possible that the granting of the permit had generated a file and that this file survived in an official American archive?

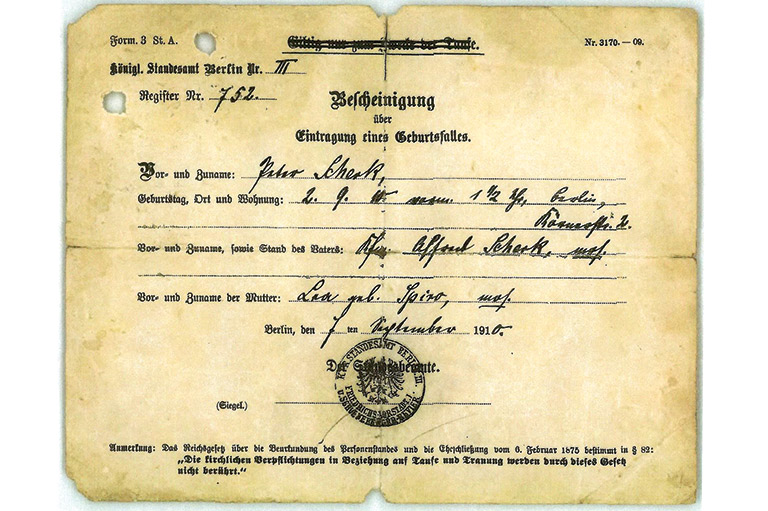

Long story short: Nine months later, and two years after my friend’s initial request for assistance, I received from the United States Department of Homeland Security a file concerning Quota Immigration Visa (also known as QIV) 23984 issued to Peter Scherk on February 2, 1939, by U.S. consular staff in Prague. And, yes! — as an attachment to the application — there was a certificate dated September 7, 1910, confirming the birth in Berlin of Peter Scherk five days earlier. It was stamped with the seal of the Second German Empire, displaying the Imperial Eagle.

There was one more document in the file. Dated June 15, 1938, it stated that Dr. Peter Scherk had no criminal record in Berlin. Like the birth certificate, it was stamped with a Reichsadler, but of a somewhat different design. This one featured a swastika.

Advertisement

At Canada’s History, we highlight our nation’s past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, while understanding that diverse past experiences can shape multiple perceptions of our history.

Canada’s History is a registered charity. Generous contributions from readers like you help us explore and celebrate Canada’s diverse stories and make them accessible to all through our free online content.

Please donate to Canada’s History today. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement