Roots: Genealogy After Death

Advertisement

Several times a year, I’m approached by someone who’s been tasked by family members with organizing the genealogical research of a recently deceased parent or other elderly relative. “We know you’re interested in this sort of thing.”

Ideally, the deceased would have arranged for a genealogical executor. Expectations would have been discussed; the arrangements would have been recorded in a directive to the executor of the estate. This directive would also have made provision to fund elements of the plan, such as the costs of publishing a family history. Contingency might also be made for compensation of the genealogical executor if the workload were to exceed the duty owed to kinship.

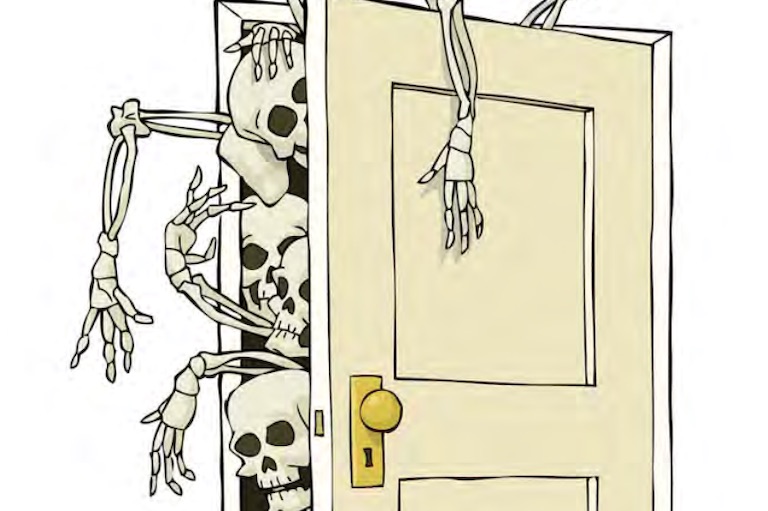

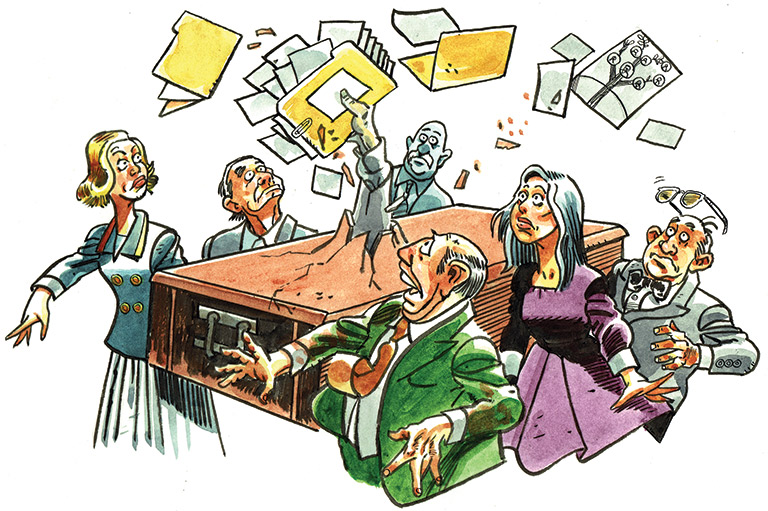

Ideally! In reality, most genealogists make no such arrangements, and the unlucky family member tasked with cleaning up the mess is typically confronted with a jumble of binders, scrapbooks, and storage boxes, as well as who knows what on hard disks and in the cloud.

One solution: Rent a dumpster. Seriously. If the deceased had so little regard for the future of the research, why should anyone else care about the work?

No one cares today, perhaps, but who can predict what might change? If you don’t have the time to wreak order today, perhaps you’ll feel differently — or someone else will — in a few years. I would buy time by securing the safe storage of paperwork, photos, artifacts, hard disks, DNA tests, and online accounts and passwords.

Let’s suppose the time to act finally arrives. What should be your priorities?

You’ll need to confront harsh realities. Unless your deceased relative was a notable person, few libraries or archives will be interested in acquiring unedited papers, genealogical or otherwise.

In addition, most repositories will be leery of accepting contributions of questionable provenance that might infringe on copyright, disregard the privacy of living people, or contain photocopies of material housed in other archives — and they’ll be reluctant to assign staff to review and to resolve these issues, unless your collection significantly advances their mission.

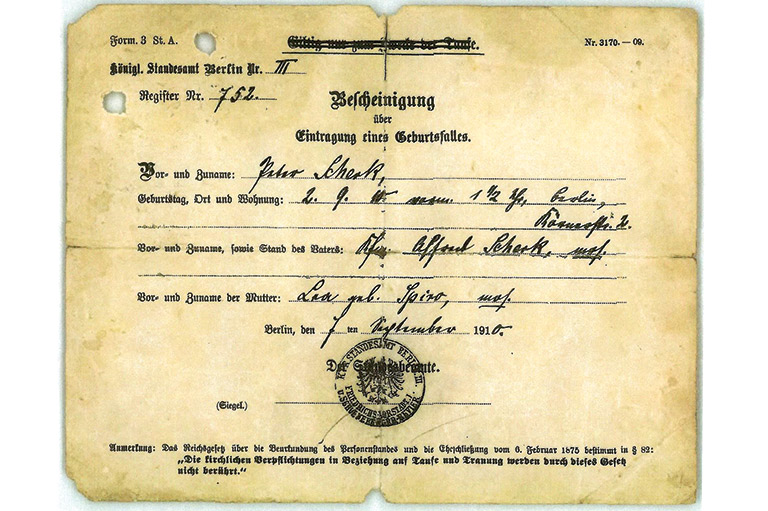

Ideally — there’s that word again — someone would adapt the research into one or more family histories that you could self-publish for posterity. (Many commercial companies can guide you through this process.) Copies of the completed history, whether paper or electronic, could go to family members, Library and Archives Canada (legal deposit), the Family History Library in Salt Lake City, Utah, and libraries, archives, and societies (genealogical and historical) in the geographical areas of greatest relevance to the research (not necessarily where the deceased lived).

If nobody is willing to undertake the effort to prepare a publishable family history, the next-best option is to extract a family tree from the research and to offer it, initially via a summary, to heritage organizations in the geographical areas covered by the research.

Be aware that every community is different in its mix of governmental and not-for-profit organizations, as well as in their mandates and priorities. Some will prefer citations rather than supporting documentation.

Be prepared for sit-down meetings (via Zoom these days) to discuss your prospective contributions.

You might also post the tree online via the likes of Geni.com, One World Tree (FamilySearch.org), WikiTree.com, or Ancestry.ca.

Artifacts and photos of historical significance, especially if they feature named people or known locations, or if they illustrate a locally significant event or activity, may interest a municipal or regional archive or museum.

In any case, all old photos should be scanned and distributed to each branch of the family.

Anything still unaccounted for after this process is likely to be expendable, although you should conduct one final review to ensure that nothing unique or irreplaceable is about to be dumped.

All in all, things would be much simpler if family historians didn’t trust in the posthumous goodwill of others and instead heeded the much-repeated and oft-ignored mantra — “Publish before you perish.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement