Famous Faces

Jean Mance

NURSE AND CO-FOUNFER OF MONTRÉAL

Born in 1606 to a bourgeois family in Langres in northwest France, Jeanne Mance founded Montréal’s first hospital. She was educated by the Ursulines — a religious order devoted to educating girls and caring for the sick and needy. Later, she likely worked as a nurse at a hospital in her hometown. In 1640, Mance learned that religious women — the Ursulines and Augustinians — had established themselves in Québec and she was inspired to go to New France. She became a member of the Société Notre-Dame de Montréal and obtained funding from benefactor Angélique Bullion to establish a hospital on the island of Montréal.

Mance, Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve, and the rest of the contingent left La Rochelle, France, on two vessels in May 1641. Once in Québec City, she met Marie-Madeleine de Chauvigny de la Peltrie, founder of the Ursulines in Québec. Impressed by Mance and her mission, Peltrie decided to join the group. They set off the following spring, reaching Île de Montréal and founding Ville-Marie. Mance quickly established a basic hospital that would later become the Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal. Through her perseverance and dedication to Montréal, Jeanne Mance paved the way for what would become the most important city in Canada between 1880 and 1950.

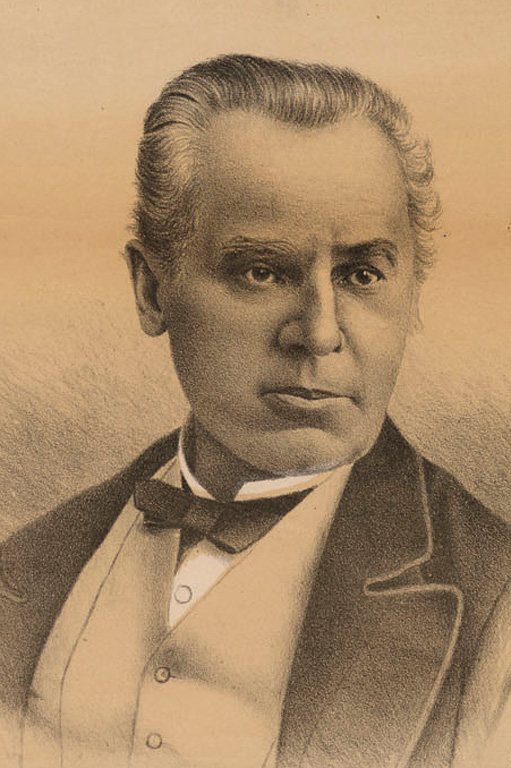

Louis-Joseph Papineau

PATRIOTE LEADER AND POLITICIAN

Louis-Joseph Papineau had a reputation as a hero and a defender of the rights of French Canadians, but he was also seen as a traitor to the nation and to the Commonwealth. Born in Montréal in 1786, he grew up at his family’s estate and studied law. After being elected to the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada, Papineau became the leader of the Parti Canadien, which later became the Patriote party. He campaigned for greater independence for Lower Canada, which was dominated by an influential British minority. He transformed from a moderate politician to a radical, openly attacking institutions such as the Legislative Council, whose non-elected members controlled the country.

In 1834, the Patriotes won a large majority in the Legislative Assembly and prepared a series of reforms, dubbed the Ninety-Two Resolutions, which would allow French Canadians to win power in Lower Canada through responsible government. The project was supported by the Governor General Lord Durham but was rejected by London. This resulted in unrest leading to the Lower Canada Rebellion of 1837–38. The poorly organized revolt was quickly suppressed, and Papineau went into exile. He returned to Canada after being granted amnesty in 1844.

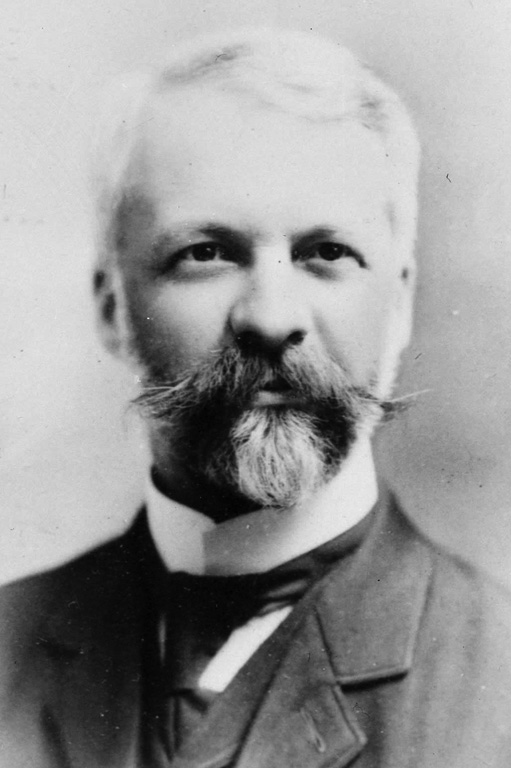

George-Étienne Cartier

FATHER OF CONFEDERATION

George-Étienne Cartier’s vision of a Canada that combined the British and French nations was the basis for the creation of our modern country. Cartier was born in 1814 to a merchant family in Saint-Antoine-sur-Richelieu, north of Montréal. He moved to Montréal at the age of ten and entered the College de Montréal. Admitted to the bar in 1835, he fought for the rights of the francophone minority and participated in the rebellions of 1837–38 alongside the Patriotes, before going into exile in Vermont. He returned the following year and became more involved in politics, becoming the right-hand man of Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine.

Elected in the Montréal suburb of Verchères, he became co-premier of the unified Province of Canada along with John A. Macdonald. This laid the groundwork for a federation of the British colonies. Cartier persuaded French Canadians that this type of union would be more sympathetic to the French Catholic cause than an alliance with the United States. After 1867, Cartier played a key role in bringing Manitoba and British Columbia into Confederation, secured the repatriation of Rupert’s Land, and pushed for the building of the transcontinental railway.

Henri Bourassa

MANAGING EDITOR AND POLITICIAN

Henri Bourassa, born in 1868 in Montréal, had a significant impact on Canadian politics through his nationalist position, which still resonates today. Throughout his career in both politics and journalism, he fought for the protection of minorities — namely Canadians in the Commonwealth and French-Canadians outside Québec. The grandson of Patriote Louis-Joseph Papineau, Bourassa was an independent thinker who became a political model for his generation and the next. He refused to take his salary as a Member of Parliament under Wilfrid Laurier and challenged the imperialist tendencies in the cabinet.

Eventually Bourassa resigned from the Liberal party and became an independent MP. He delivered many speeches calling for Canada’s complete independence, going so far as to oppose the Dominion’s involvement in the First World War. In 1910 he founded the newspaper Le Devoir to share his perspective. He gradually gave up politics but still had significant influence. In fact, his plan for Canadian independence from the British Parliament became reality in 1931, with the signing of the Statute of Westminster. By the 1960s, his idea of a bicultural Canada had made its way to Parliament, where it was promoted by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau.

Thérèse Casgrain

SOCIAL JUSTICE CHAMPION

As the first female leader of a political party in Canada, Thérèse Casgrain changed the political landscape forever. Born in Montréal in 1896, Casgrain was the daughter of businessman and politician Sir Rodolphe Forget and Lady Blanche MacDonald. In 1916 she married Pierre Casgrain, a federal Liberal politician. In the 1920s, she helped found the Provincial Franchise Committee for Women’s Suffrage and began fighting for the right for women to vote provincially in Québec — a battle that would last more than two decades before victory was achieved. During this time, she also championed human rights while serving on various federal councils and founded several associations that worked for the welfare of women. In 1942, she ran for federal election as a Liberal and lost. In 1951, she was elected as the leader of the Québec wing of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, becoming the first woman to head a Canadian political party. In 1970, then-Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau appointed Casgrain to the Canadian Senate. She died in 1981, leaving a powerful legacy of championing the rights of women and the underprivileged.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement