Virtual Talking Circles Keep Métis Michif Alive

A small group in the municipality of St. Albert, northeast of Edmonton, is working to ensure Métis Michif becomes a language of the future and not a mere echo of the past.

Founded in 1861 as a Métis community, St. Albert is today the base of the Michif Cultural Connections group that celebrates Métis culture through beading, jigging, and moccasin making and that offers classes in Michif.

The language and its dialects have historically been spoken by Métis peoples across Western Canada. Michif combines Plains Cree grammar with a mixture of French and Cree vocabulary.

Since 2017, Michif Cultural Connections has been holding language classes for dozens of students who gather at the historic Juneau House. Built in 1890, it’s St. Albert’s oldest existing residence — but classes shifted online in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Joshua Morin, the group’s office manager, has been leading the weekly ninety-minute courses for just over two years. His grandmother Thelma Chalifoux founded Michif Cultural Connections in 2004, following her retirement from the Senate of Canada, where she served as the first Métis woman senator.

Morin speaks a dialect known as “Southern Michif” that is used in Métis communities along the Red River in Manitoba, as well as in other parts of Manitoba and in Saskatchewan. The beginner-level classes focus on pronunciation, simple nouns and verbs, and basic conversation. A recent class included twenty-seven students from around North America.

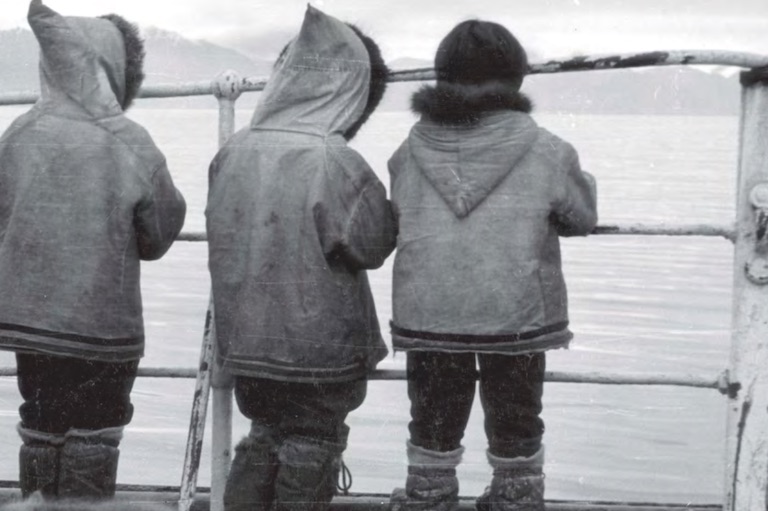

“They’re classes, but I call them virtual talking circles,” Morin said. “I don’t approach them like a colonial class. I can’t give students a test and then fail them. This is a language of the land; it was a language taken from us [in residential schools]. The circle is inclusive, and non-Métis people can take the class.”

For the online lessons, Morin uses PowerPoint slides based on teaching resources from the National Centre for Collaboration in Indigenous Education and the non-profit Prairies to Woodlands Indigenous Language Revitalization Circle (P2WILRC). Students can also access Michif resources, like the P2WILRC’s online “Michif Talking Dictionary (Li liivr di Moo aañ Michif)” and the Heritage Michif To Go app from the Gabriel Dumont Institute.

By the time one of the eight-week courses wraps up, students are expected to be able to introduce themselves in Michif, to ask basic questions, and to identify objects.

Even though he’s Métis, Morin was raised in an environment that was mostly English-speaking. Seeking out Michif was a step toward reconnecting with his identity.

“My grandmother collected a lot of Michif books. She had one of the first Michif dictionaries, Turtle Mountain Chippewa Cree. It was my first look into the language,” Morin said.

He began learning to speak Michif when he met lifelong speaker Graham Andrews through Michif Cultural Connections. Andrews learned Michif from his aunts and grandmother while growing up in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan.

“I refuse to call myself a teacher,” said Andrews, who sometimes helps out with Morin’s classes. “As Métis people, we share. It just so happens that I get these opportunities to share.”

While the virtual sessions have connected students as far away as North Dakota and Nova Scotia, the format has brought its own difficulties.

“[Before COVID] everyone was in a circle, and you could see everyone’s faces in person. Getting used to talking to people on a screen was very challenging. But we got through it, and everyone was really appreciative,” Morin said.

Candice Behrendt, a Winnipeg Métis student, began joining the virtual classes along with her two daughters about eighteen months ago. “My goal is for [them] to learn Michif and be more fluent than I am, and hopefully their descendants will be even more fluent,” she said.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

At the start of the course, Behrendt said she was at a “very basic” level and learned what she could from Michif dictionaries.

“Trying to pronounce the words using an app or dictionary is quite difficult. It’s nothing like having somebody talk to you,” she said. “Now I can hold a basic conversation. The things we learn are relevant to our cultural values, like inviting people in for tea, or saying ‘this is my grandmother,’ or ‘this is my sister,’ or ‘it’s cold outside today.’”

There is urgency to the efforts of those learning Michif. Almost all fluent speakers of the language are elderly, and the window in which to benefit from their advice and experience is closing.

According to a 2016 Statistics Canada census on Indigenous languages, less than two per cent of the total Métis population in Canada could then speak an Indigenous language. Of that number (a little less than ten thousand people), almost three quarters spoke either Cree or Dene, and just over a thousand could speak Michif.

Heather Souter, a Métis linguist and Michif teacher, did not grow up speaking the language but has spent the past twenty years honing her proficiency. Today she is a sessional lecturer of two Michif classes at the University of Manitoba and also operates P2WILRC.

Souter, who rates her own language procifiency at “midlevel intermediate,” said it will take decades of dedicated effort to grow the number of Michif speakers to the point of sustainability.

“People want change now, but to make our languages vital again — when we already have two, or three, or four generations without their language — we can’t expect a book, or ten years [of language-learning initiatives] to get our language back,” she said. “It’s faster to lose something than to regain it. It’s going to take thirty years of concentrated effort to bring back any kind of reasonable number of proficient adult speakers.”

To get there will require countless hours of personal study and practice by Michif learners. It will also require the creation of opportunities for Michif to be regularly spoken.

“I’ve seen people able to use the language when working for Parks Canada at the Riel House National Historic Site,” Souter said. “[But] the bottom line is, without creating opportunities outside of institutions for people to use Michif, and most importantly families, it’s really hard for people.”

Back in St. Albert, Morin agrees that there is still much more work to be done. But he’s also encouraged by the momentum that Michif Cultural Connections has helped to create towards revitalizing the language.

“I hope that with the next generation there won’t be a need for beginner classes,” Morin said. “There can be intermediate classes, because they’ll be learning beginner [level] at home. That’s our goal.”

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!