Rooted in Resilience

This year’s sesquicentennial commemorations are a striking reminder that the story of Canada can be told in countless ways from many diverse perspectives. However, it is also clear that some stories are told more often than others. Popular histories of Confederation and the birth of the country are deeply rooted in the world views Europeans brought with them to North America. Their values, beliefs, and ideals, as well as their political, economic, and social systems are reflected in conventional accounts of the past. Yet these narratives aren’t the only versions of events.

Long before Confederation, Indigenous peoples shaped the physical, political, and economic landscape of what we today call Canada. Their experiences attest to alternative versions of history. Their stories challenge what we know and believe about our past and offer valuable insights into the workings of contemporary Canada.

Indigenous peoples in Canada are subject to Canada’s laws, rules, borders, and policies. Yet many have held on to, and continue to carry out, their own governance-related procedures, rituals, and ceremonies. These practices are often tied to sophisticated methods of managing resources as well as to their political relationships.

For instance, the Iroquois confederacy’s Great Law of Peace is an incredibly detailed history and oral constitution. It defines the rights and duties of individuals, families, and leaders, and it outlines traditional ways of governing, including the rules and makeup of councils, hereditary laws, decision-making processes, record-keeping practices, and so on. The Anishinabe and the Blackfoot confederacies developed sophisticated clan-based systems of governance. Readers might be familiar with the Pacific coast potlatch ceremonies, but they may not know the potlatch’s role in governance. The ceremonies — which included lavish gift-giving — marked important events and were used to confer and to validate names, privileges, and social rank.

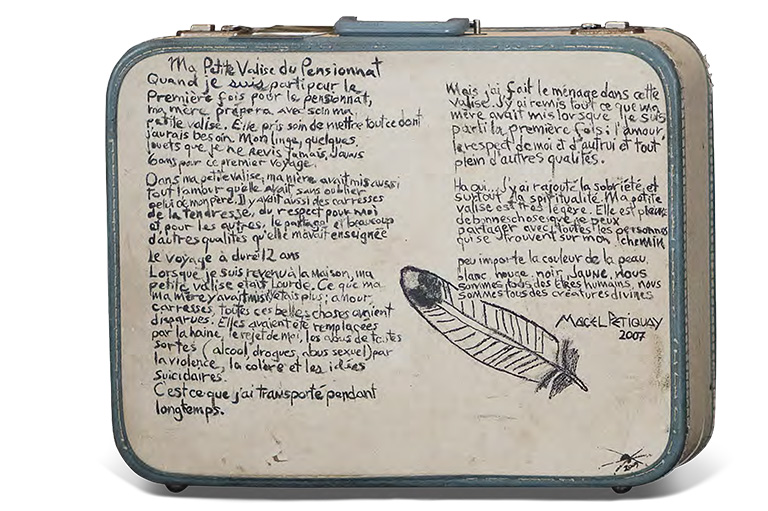

Centuries of colonization and harmful government policies such as residential schools, segregation, and discrimination led to the erosion of traditional styles of governance. Yet all across the country, Indigenous communities continue to work towards independence, self-sufficiency, and building a more just and equal relationship with the Canadian government. The following examples explore the history of governance in Indigenous communities that are today striving to rewrite conventional understandings of history and to gain control over their past and present.

Wampum Diplomacy

Wampum belts are not just beautiful gifts offered during historic agreements between Indigenous and settler peoples, nor are they simply works of art or currency. They form part of an important governance tradition, called wampum diplomacy, used by the Anishinabe, Haudenosaunee, Mi’kmaq, and others. Alongside other traditions, such as storytelling and the divvying up of responsibilities among clans, they exemplify distinct ways of governing and of understanding political relationships.

Wampum are small tubular beads, made mostly from whelk shells and quahog clamshells native to the east coast of North America. Strings of these beads are woven into intricate patterns, complex sets of icons that represent significant relationships between nations. The symbols can be read using specific sets of rules and conventions, becoming concrete records of the relationships they depict.

Contrary to the persistent stereotypes of Indigenous peoples as strictly oral and non-literate, wampum belts illustrate “widespread development of symbolic literacy across multiple Indigenous nations,” said Lynn Gehl, an Algonquin Anishinabe Kwe writer, advocate, and artist who holds a doctorate in Indigenous studies.

Gehl, who wrote The Truth that Wampum Tells, has analyzed the wampum belts exchanged during the signing of the 1764 Treaty at Niagara. These belts confirm the terms set out in the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which outlined the guidelines for European settlement on Indigenous lands in North America.

She has argued that these belts are constitutional documents: “It is with these three belts that the Indigenous understanding of Canada’s constitutional beginnings is codified. And it is in this way that the [1763 Royal] Proclamation is only one of Canada’s first constitutional documents.”

The three wampum belts were exchanged following the lengthy discussions and decisions that took place during the treaty process. One of the belts depicts “a chain secured to a rock on Turtle Island, running through the twenty-four Nations’ hands, and attached to a British vessel,” Gehl wrote. “This represented the negotiating process Indigenous nations were to take to ensure their equal share of the resources and bounty of the land.” As such, the belts codified an equal relationship between independent allies.

As with contemporary constitutions, great care is taken to preserve wampum belts. The belts are carefully kept by wampum keepers, individuals who are responsible for preserving wampum records and knowledge.

Over time, many wampum belts have been lost, stolen, or otherwise removed from Indigenous communities. Some have been repatriated. Remarkably, several of these belts’ meanings and stories have been kept alive underground, like much Indigenous knowledge over the last few centuries of colonization. Though they are often the subject of much debate, these belts and the alternative narratives they embody challenge national histories of Confederation. They offer important context for the breaches of treaties that followed the founding of the country as well as land claims in present-day Canada.

Reef-net Fishing

Reef-net fishing is a traditional way of catching salmon that’s unique to the Strait Salish people of present-day British Columbia. The method is used in the Salish Sea — an area of coastal waters off southwestern British Columbia. A net is suspended between two canoes using a set of underwater anchors. Water is funnelled in through the use of a lead in front of the nets. To be effective, reef nets must be used in specific locations, and their use requires detailed knowledge of salmon migration patterns, tide flow, and the local environment.

“It is more than just a fishing technique,” Nick Claxton, a member of the Tsawout band and WSÁNEĆ nation, wrote in his Ph.D. dissertation. “It is a model of governance over an integral part of what it means to be a WSÁNEĆ person.” Claxton, who teaches at the University of Victoria, said the Saanich reef-net fishery’s history is intimately connected to the values, spiritual beliefs, economics, social system, and self-governance of Indigenous communities once sustained by salmon. For the Saanich peoples, the reef-net fishery is based on a profound spiritual respect for the salmon and for the interconnectedness of the environment and all living things. This holistic perspective is inherently linked to a distinct way of sustainable governance of the land, its resources, and the people living within it.

Within this system, each Saanich family was headed by the CWENÁLYEN. The CWENÁLYEN was most often the elder in the extended family unit. These captains were responsible for passing down and overseeing Saanich fishing practices, history, laws, teachings, and knowledge. Through generational transmission, they upheld governance structures that protected a Saanich person’s right to NE,HIMET — that is, their right to their personal belongings, their reef net, their fishing and camping locations, the longhouse, and access to fresh water. Family fishing locations, or SWÁLET, were of particular importance given the complexity of reef-net technology and were passed down with family names. As emphasized by Claxton, reef-net fishing “formed the core of Saanich society” and allowed members of the community to maintain their unique identity and way of living.

Reef-net fishing was made illegal by the British Columbia government in 1916. Scholars such as Claxton have since argued that the ban contravened the 1852 Douglas Treaty. That treaty between the pre-Confederation colonial government and the Saanich nation outlined the Saanich right to carry on with their fisheries, to “fish as formerly.”

As Claxton asserted in an article, since “WSÁNEĆ people’s traditional governance, social organization, and use of the land and resources, including the reef-net fishery, were all intertwined … [this right] means more than just the right to fish…. It means a right to ownership of all those fishing locations … and to the system of governance that stood in WSÁNEĆ for thousands of years or more.”

Nevertheless, a later provincial government saw reef nets as “fish traps.” The new regulations soon dismantled traditional fisheries, forcing the Strait Salish to adapt to European methods of self-sustenance and resource management. Saanich claims to traditional fishing rights and to the lands of which they were dispossessed remain unresolved today.

In spite of this troubled legacy, Saanich people are striving to revitalize reef-net fishing as well as the key role it played in Saanich society. “A new relationship needs to be forged between First Nation peoples and the state,” said Claxton. “Historic treaties such as the Douglas Treaties should be recognized as such; then a new nation-to-nation [relationship] could emerge where both nations have something valuable to offer, and both could prosper not at the expense of each other, or at the expense of the environment.”

Métis Buffalo Hunt

Buffalo Hunting in the Summer by Peter Rindisbacher, 1822. Throughout the nineteenth century, hundreds of Métis families came together to participate in seasonal, large-scale buffalo hunts across the western prairies. The herds of bison provided these communities with a stable food source, formed the centre of their mobile economy, and helped to shape a distinctly Métis form of self-governance.

Buffalo hunts were an organized affair. Métis families from different regions pooled their resources and skills to ensure their mutual safety and to make certain that every family benefitted from the hunt. The distribution of responsibilities and duties was determined through open discussions, voting processes, and the election of temporary leaders, including a chief of the hunt and several captains who oversaw smaller hunting parties.

Adam Gaudry, assistant professor in the Faculty of Native Studies and Department of Political Science at the University of Alberta, said the hunt was organized in a manner that we would today call democratic, and it facilitated the coordination of hunting strategies and armed resistances when necessary. The authority of the leaders was temporary, preventing power from becoming concentrated in one place. This helped Métis communities to work together while also maintaining the independence of separate families. Notably, families were not forced to partake in hunts or military confrontations but were able to choose whether to join in.

“The democratic strength of the Métis community … lies in its organic forms of governance and its ability to organize itself without centralized authority,” Gaudry wrote in his 2009 thesis on reclaiming Métis cultural spaces. “Traditional Métis leadership is situational, and never coercive. Since consent to leadership could be revoked at any time, all Métis life remained independent of a permanent centralizing force like a state system.”

The freedom to live independently was a fundamental element of Métis identity. The lifestyle, however, was not without its duties and obligations. Métis values and governance were — and continue to be — deeply rooted in kinship and family, said Gaudry. Métis people maintained extensive family networks and could call upon each other in times of need, knowing that help would be returned in the future if needed. Significantly, family ties often went beyond national, religious, and language barriers, resulting in a diverse set of intertwined communities. For instance, while many Métis were Catholic and French- or Michif-speaking, some were Protestant and English-speaking, while others followed traditional Indigenous spirituality and spoke mostly Cree or Ojibwa.

Métis governance, anchored in consensus and kinship, shaped Métis history in ways that stretched beyond the buffalo hunt. Buffalo hunt tactics informed Métis resistance against Canadian incursions into their territories. The model of the hunt was used by Métis men to take Upper Fort Garry in the 1870 Red River Resistance and again to combat federal government forces at the 1885 Battle of Batoche. Communities brought their values and governance strategies with them as they moved west and formed new settlements.

Over time, they had to deal with new obstacles. As white settlers rapidly colonized the West, the buffalo herds disappeared, and the Métis lost a major source of subsistence and suffered widespread discrimination. Still, their desire for independence, self-sufficiency, direct participation in politics, and lasting kinship ties endured. These values continue to resonate in modern Métis communities and in their efforts to establish contemporary self-governance.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.